FEATURE: SIGNAL BOOST

By Rafael Soldi | May 11, 2019

This week on Strange Fire we are highlighting our recent exhibition, Signal Boost, curated by Jordan Rockford and Rafael Soldi at NAPOLEON in Philadelphia.

In the last decade, social media platforms have quickly become engines for amplification, allowing organizing and sharing of messages on a global scale. This new tool, signal-boosting, has proven to be both conducive of change, and catastrophic to our democracy. Strange Fire Collective has used its platform and reach to signal-boost relevant work made by women, people of color, and queer and trans artists, writers, and curators who reflect our time. For Signal Boost, curators Jordan Rockford and Rafael Soldi have selected three photographers to amplify from the Strange Fire roster, whose work speaks to the Society for Photographic Education's 2018 National Conference theme, Uncertain Times: Borders, Refuge, Community, Nationhood. Artists Lorenzo Triburgo, Zora J Murff, and Juan C. Giraldo explore questions of migration, identity, borders, and how we occupy space as fellow citizens in this country.

With support from NAPOLEON, The University of the Arts, and The Society for Photographic Education

Above: © Juan C. Giraldo

BLUE & BLUE

In his own words, Juan C. Giraldo’s photographs “explore the lives of people whose experiences closely mirror my own. I was born in Manizales, Colombia and raised in Paterson, New Jersey, after my parents, brother, and I moved there in 1981. Paterson is a working class city, similar to the working class cities where my subjects live. I moved to Chicago in 2012 and began to photograph the Great Lakes Reload (GLR) on Chicago’s far southeast side. GLR is a 385,000 square foot warehouse that transports, stores and processes various types of steel products. Over time, GLR came to feel eerily familiar. The smell of diesel and cigarettes started reminding me of the loading dock I worked on in my youth: GLR’s dock workers share qualities with so many of my family members, former co-workers, and friends. In their stories I see echoes of my past. They are tough, strong, and they endure.

Through photographing the GLR employees, I became familiar with the narratives of their personal lives and relationships; the ties that bind friends, co-workers and families emerged as the relationship of photographer and subject became more intimate. As I documented their lives, a strong bond emerged which allowed me to photograph my subjects as I would my family. In their stories I see echoes of my past.”

www.juancgiraldo.com

Above: © Lorenzo Triburgo

POLICING GENDER

Policing Gender is an installation of photographs and audio by Lorenzo Triburgo. He began the project by corresponding with 32 LGBTQ-identified prisoners. The photographs are abstract metaphors on absence and imprisonment and the audio component is a compilation of voices of LGBTQ prisoners with whom he corresponded on a long-term basis.

Triburgo employs visual connotations of landscape and portrait photography to cast a critical lens on prison abolition as a crucial queer issue. The photographs of draped fabrics recall the lush backdrops in renaissance portraiture; however, these “portraits” are figureless, leaving the viewer to contemplate the absence of those who are behind bars.

The aerial landscapes were photographed from a hot air balloon and metaphorically describe the construct of prison and punishment. The aerial viewpoint connotes a position of power, and while looking down on the visually-disorienting scale of the landscapes one notices that where there should be sublime grandeur, there is instead containment.

www.lorenzotriburgo.com

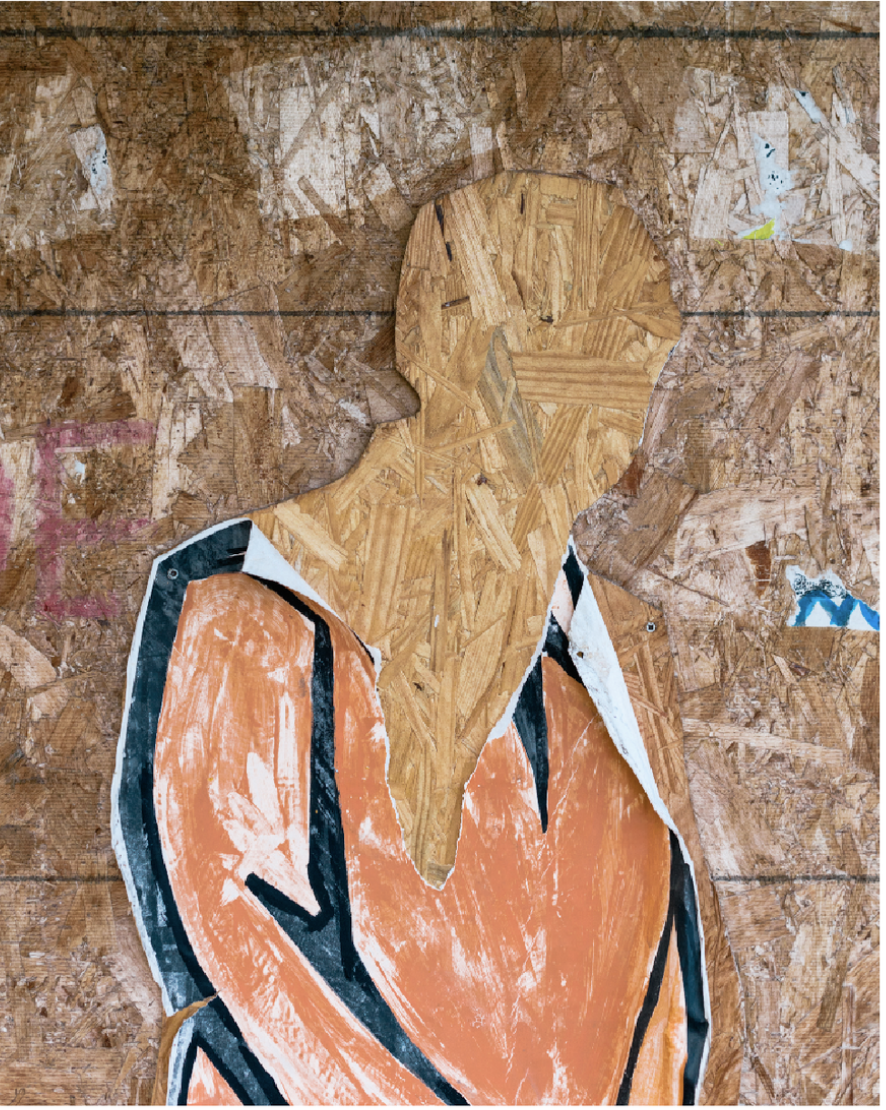

Above: © Zora J Murff

AT NO POINT IN BETWEEN

For many African-Americans, the Great Migration from the Jim Crow South was a search for hope. However, oppression followed them in the forms of continued racially motivated violence and prejudicial housing policies. Like their ancestors following Emancipation, Black individuals found themselves in an environment of perceived freedom.

Photographing in the historically African-American neighborhood of North Omaha, Nebraska, Zora J. Murff’s survey examines not only race, segregation and financial disenfranchisement, but also how policies predicated through systemic white supremacy are a form of violence.

We perceive violence dichotomously between fast and slow, and readily understand forms of fast violence—like lynching—because they are reinforced by our narrow perception of what it means to be at risk. Forms of slow violence—like redlining—are not so easily understood because their effects only become visible after long periods of time. The slow violence of these policies pushed African-Americans into the North Omaha neighborhood and kept them there.

Murff represents slow violence through photographs of the architecture and surrounding landscape, those who inhabit it, and by referencing the tumultuous local histories of fast violence spurred by racism. The portraits are points of confrontation with those who are affected by slow violence, and emphasize a push and pull between intimacy and distance.