Q&A: Zoë Zimmerman

By Hamidah Glasgow | April 28, 2016

Zoë Zimmerman is a photographic artist who examines male behavior, particularly “touch” and platonic intimacy and the ways societal and cultural biases set the parameters for physical relationships.

Zoë was born in Manhattan, New York, and raised from an early age in Taos, New Mexico.

Encouraged by an artistic family and community, she began taking photographs when she was quite young. Zoë graduated from high school at age 16. She then landed a job printing the life’s work of the late Lauren Gilpin at the Amon Carter Museum of Art under the tutelage of curator and author Martha Sandweiss. She worked there for one year before being accepted to the Rhode Island School of Design, where she graduated with a BFA in photography in 1986.

Directly out of college, Zoë began exhibiting her photographs. She immersed herself in antique photographic processes, producing platinum print portfolios for Aaron Siskind and albumen prints of her own work. Through the use of large format cameras and alternative processes, she honed her skills as a fine art photographer. Zoë returned to New Mexico in 1990 where she embraced a life of creativity, family and strong community. Since then she has exhibited her work consistently and has sought a balance between art-making and parenting. This dynamic and its graceful execution informs her life and her work.

Zoë ’s work is in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art, The Museum of New Mexico, The Harry Ransom Center for the Humanities, and many other public and private collections. She is represented by The Photo Eye Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico. _ Lenscratch

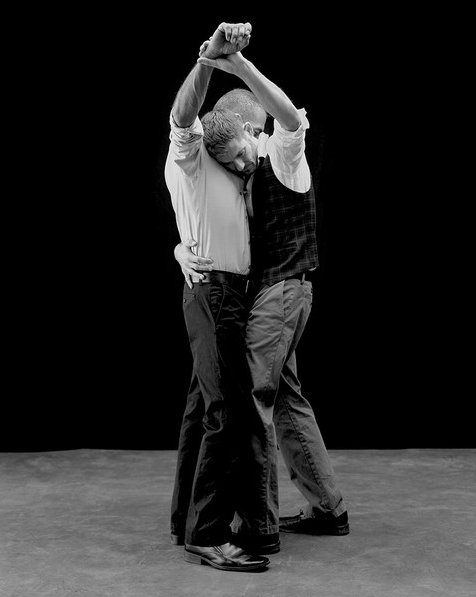

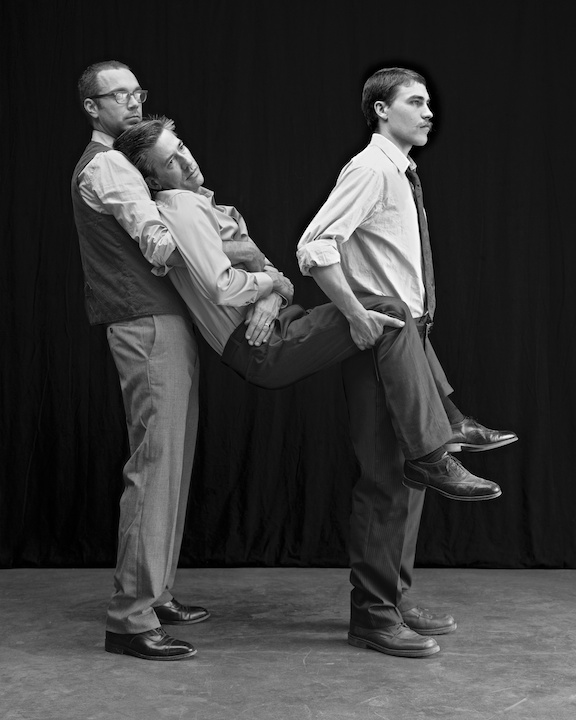

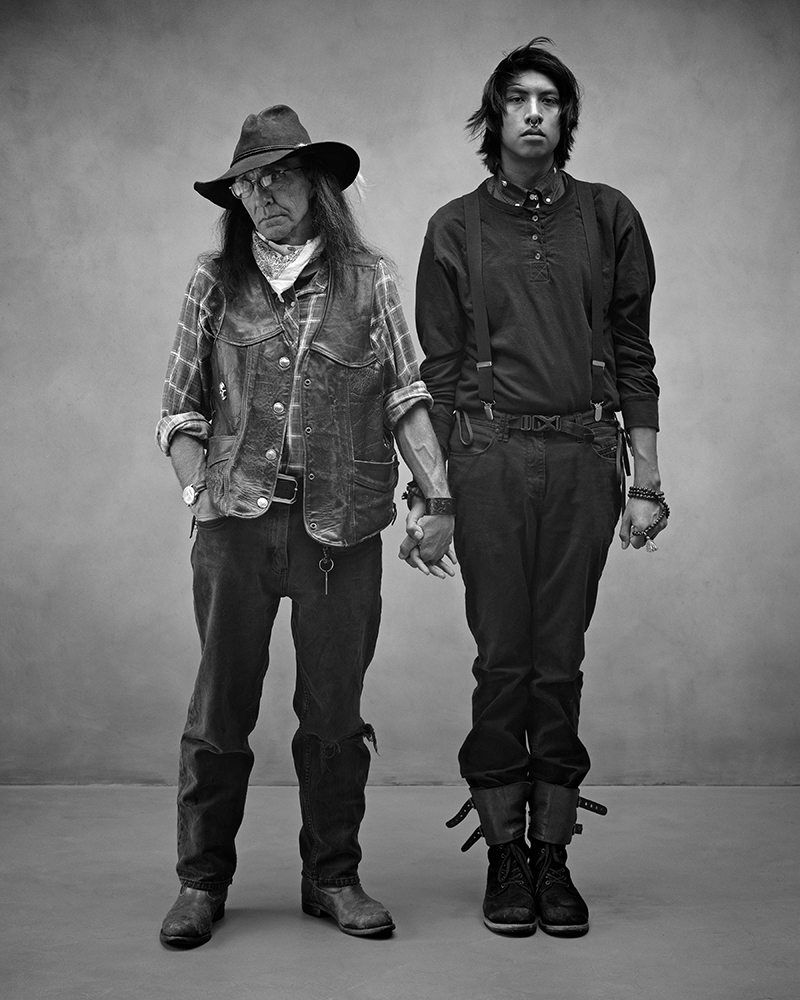

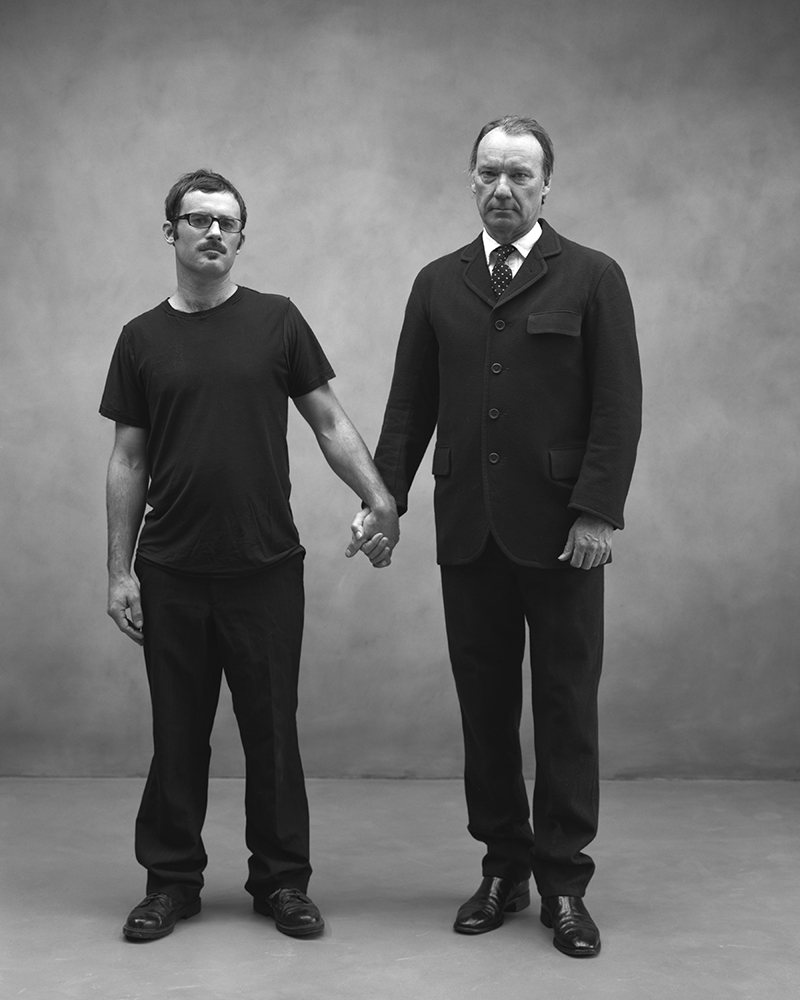

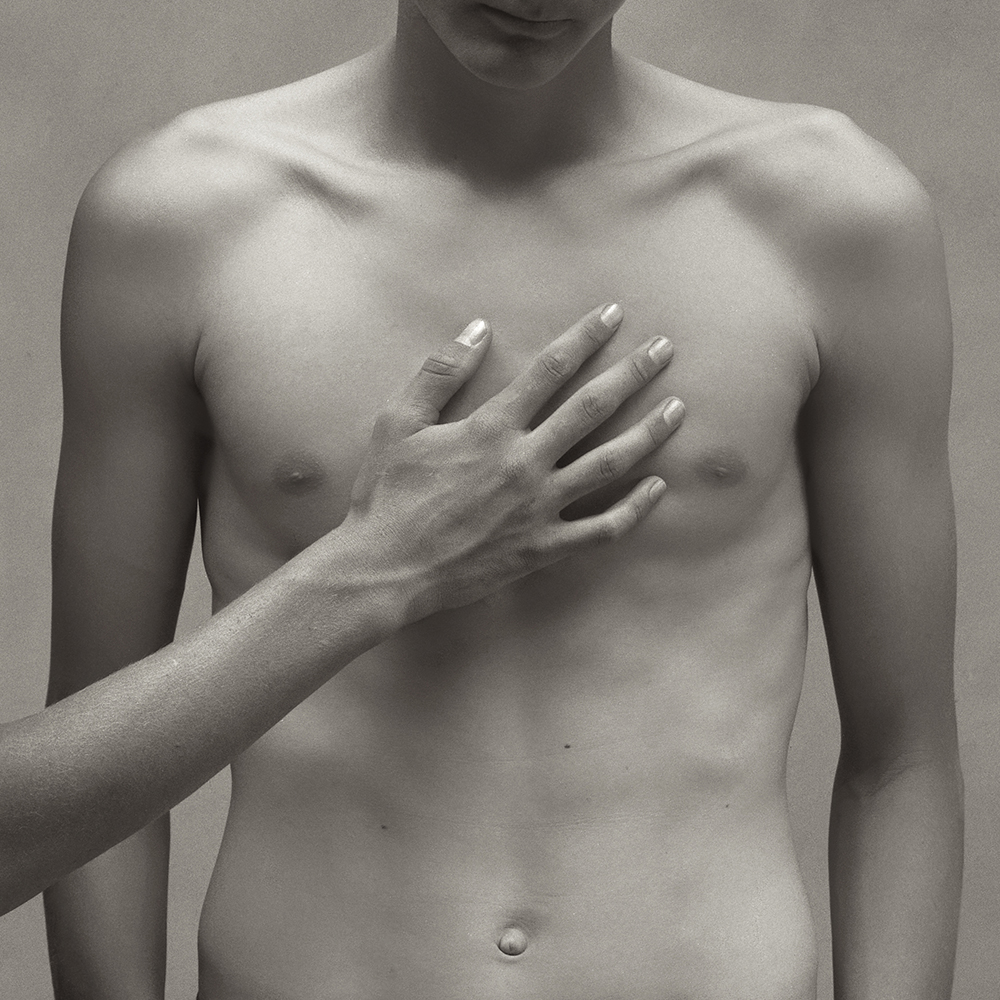

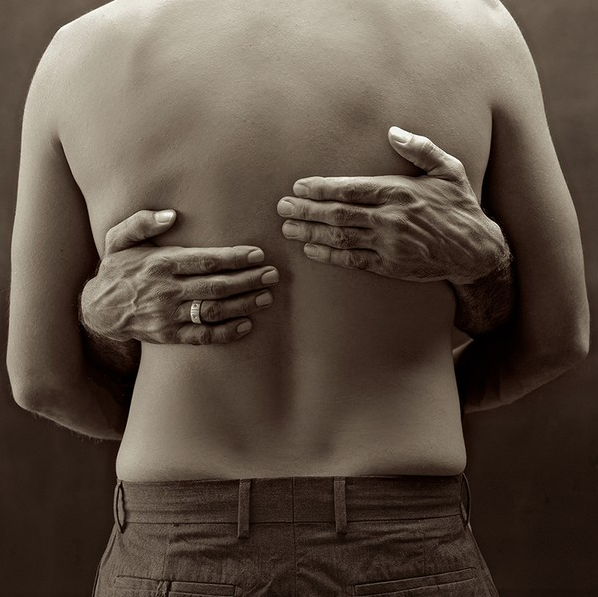

Of Men: Strength and Vulnerability

This project, in three parts, is an examination of male behavior, platonic intimacy and how cultural biases set the parameters for physical relationships. Broadly, the work addresses homophobia, but more specifically the work defines a pattern of ‘ touch isolation ‘ experienced by men in our society.

Hamidah Glasgow: This series is a departure from your earlier work. How did this work develop and become what it is today?

Zoë Zimmerman: The project at its inception came to me from two very different sources. First, there was the visual inspiration and then there was the emotional impetus. The images from the first aid manual, which are the cornerstone of the series, had been floating around in the detritus of my psyche (and my studio) for many years. I was drawn to the images of men in heroic stances caring for one another in their staid, generic man-costumes, but it took me years to decipher what it was about the images that moved me and how I could utilize that in my own work. The key to the emotional inspiration behind the project was a simple moment in the long haul of child rearing. After a childhood filled with healthy, comforting physical contact there was a moment in my son’s early adolescence when I looked at him and thought, ”When was the last time anyone touched that boy?” The realization was profound for me that there is a point when everyone (including mothers) stops touching the boy children and these children stop putting their arms around their friends and that this touch isolation continues into manhood. The simple question of who men are allowed to touch was particularly heartwrenching for me because in contemplating it I realized that the answer is: virtually no one.

HG: Did you envision the three parts to the project first or did that develop over time?

ZZ: I did not envision three parts to the project initially. I started with the first aid pictures and thought that would be sufficient but as I worked I found that the pictures were one-dimensional illustrations of an idea that is multifaceted and that I needed to come at the topic from another angle.

The next section of the project is called Care, and though it is also loosely based on illustrations from a medical text, it delves more deeply into the discomfiture of men in physical contact with each other- or maybe it is the audience that is made uncomfortable with the intimacy of this series. The third section Holding Hands was not preconceived but began with a spontaneous studio moment. I asked two of my subjects to hold hands and the results were so interesting to me that I continued the idea.

HG: Each part of the project delves a little deeper in its exploration of physical intimacy- non-romantic intimacy- between men. The persistent tension in the images is a powerful reminder of your premise and the difficulty that men face. Your exploration of “Care” and that of “Heroes” is especially compelling. Can you tell me more?

ZZ: There are varying degrees of intimacy between the men in each part of the project, starting with the first aid pictures, which are depictions of men engaged in what we as a society would deem “appropriate touch.” In each picture, there is a subject in a weakened state and a hero coming to his aid. The contact, though physically intimate, is acceptable because of the rescue aspect. We do not, apparently, begrudge the touch of heroes. Which must be why if we see imagery of men in nurturing positions with each other at all it is usually soldiers, doctors or firemen- the rescuers, the heroes.

The ‘Care” section of the project could be perceived as the most intimate of the three. There is more hand on skin; some ambiguity as to what necessitates the contact. The pictures are cropped closer so that the viewer has to be more intimate with the subjects as well. These images are a projection or a fantasy of how the world might look if men were comfortable with basic physical nurturing from each other. There is a closeness portrayed that might be how men could comfortably interact without the spectre of homophobia dangling about. I find the intimacy in these images unusually sweet, but honestly, in creating them, I found it difficult to steer clear of the homoerotic: to avoid homosexual reference or sexual reference at all.

That being said, I think the hand holding pictures most accurately depict men’s discomfiture with fraternal intimacy. Who knew that this simple act of clasping each other’s hands could be so charged? Photographing this series was truly an exploration of excruciating awkwardness. And so in some ways, though forced upon my subjects, the level of intimacy of men holding hands is rather profound.

HG: You mentioned that to some degree "touch Isolation" is generational. Can you elaborate on that?

ZZ: It has been my observation that things are changing by increments; slow change toward a kinder society. I have watched my son’s generation (presently college age) and there seems to be more fluidity of sexuality and therefor more fluidity of definitions and less animosity based on sexual preference. Whereas, the delineation used to be ‘straight’ or ‘gay’ there now seems to be every variation, lots of acceptable grey area, and maybe as a result of that accepted fluidity there is less of a fear that physical closeness between men will automatically be interpreted as gay. But my son attends a very liberal college where there is probably an overabundance of awareness and compassion. There is also a geographical component. I think there are definitely parts of the USA where there is no noticeable change. When visiting the Texas panhandle, my brother in law has to remind my husband not to greet the ranch hands with a hug.

This touch isolation also seems to be cultural. While working on the project I traveled to other countries and observed men’s interactions with a heightened awareness and found that the stigma against touch does not exist everywhere.

HG: I find the image, Fireman’s Carry Fig 110, profound. These two figures exemplify human nature in its true manifestation. We alternately provide and receive love and care from others. This fundamental aspect of humanity is important to remember and your image is a meditation on the balance of life.

ZZ: Thank you.

HG: Tell me what you are working on in your studio these days? What is next for you?

ZZ: I'm turning the project into a book and I am still interested in showing the body of work further afield. I am still working on the project. I'm not ready to let it die.

As far as new work goes I have a few ongoing projects, one of which is an honest look at marriage entitled ' Marriage: a cautionary tale' and also a series of portraits of my daughter in fantastical situations that is a collaboration between the two of us that we've been working on since she was three years old. I think that I want to show that project when she turns sixteen which will be in two years.

HG: Did I mention that this series, especially the first image in this post, has touched me very deeply? I have the two men and their dependence on each other etched in my brain. Again, I want to thank you for making this work and starting these conversations.