Q&A: william camargo

By Jess T. Dugan | October 29, 2020

William Camargo is a photo-based artist, educator, and arts advocate. He received his MFA at Claremont Graduate University and his BFA at the California State University, Fullerton. His work has been featured at venues such as Chicago Cultural Center (Chicago, IL), Loisaida Center (New York, NY), University of Indianapolis (Indianapolis, IN), Mexican Cultural Center and Cinematic Arts (Los Angeles, CA), and The Ethelber Cooper Gallery of African and African American Arts at Harvard University (Cambridge, MA). His work has been published in The Chicago Tribune, The Guardian, The New York Times, OC Weekly, TIME, and others. He was awarded residencies at the Artists’ Cooperative Residency and Exhibitions (ACRE), the Chicago Artist Coalition, Project Art, and at Otis School of Art and Design’s LA Summer Program. He is one of the selected recipients of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, and the Leo Freedman Foundation Grant. He is currently serving as Commissioner of Heritage and Culture for the City of Anaheim. He is the founder/curator of Latinx Diaspora Archives. He works and lives in Anaheim, CA.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello William! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. Let’s start at the beginning: what originally drew you to photography and art-making, and what was your path to getting to where you are today?

William Camargo: Thank you, Jess. First I want to mention I am a huge fan of your work. I came to photography, I would say, accidentally. I was in high school during my senior year and wanted to take an easy class, that easy class I thought was photography. I had already been engaged with photography, as I would say I was the unofficial family photographer. I would use my family’s point and shoot camera that was always ready with some 35mm film. While in high school, my teacher noticed my interest in photography, so with the few SLR cameras the school carried, lent me one in the second half of the school year.

I was on a path towards biology and had already been accepted to a 4-year university in Southern California. I had this idea that I needed to study something that would get our family out of poverty and that was going into medicine. As a first-generation college student, it was tough to drop that, but I just didn’t have the passion. I just didn’t show up to the first day of college, and instead, last-minute enrolled in a community college where I found that photography and art was the path I wanted to take. I tried all types of photography: fashion, products, and for around 6-7 years, I was a photojournalist. I had this faux idea of doing conflict photography, I wanted to be in these situations, which when I think about it now I was super naive about that work. I did cover some conflicts in Mexico, Central America, and Cambodia and realized that maybe losing my life for a photograph that may not be seen was not worth it.

I deeply cared about social justice issues, especially seeing what was happening in Chicago during a 4.5-year stint there, but I decided to leave photojournalism and work towards a different framework, where I did not have to be objective to the things I was seeing in Chicago. I wanted to be outspoken, I wanted to help, and I just couldn’t do that as a photojournalist to the extent I wanted to. That is how I ended up doing new work. I had already graduated with a degree in creative photography and decided to use those tools I learned and put theory into practice.

Damn I Can't Play On This Side of the Park?, 2020

JTD: I’m interested in your project Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories and Possibilities, which you describe as “a long term research project that includes performance, portraits, landscapes and archived material from the city of Anaheim. It is reflective of a city that battles with its racist history that has repackaged it in a new form, through police violence, gentrification, and capitalism.” Can you tell me more about this project? What was the impetus for its beginning? Is it currently in progress? What do you envision as its final form, or forms?

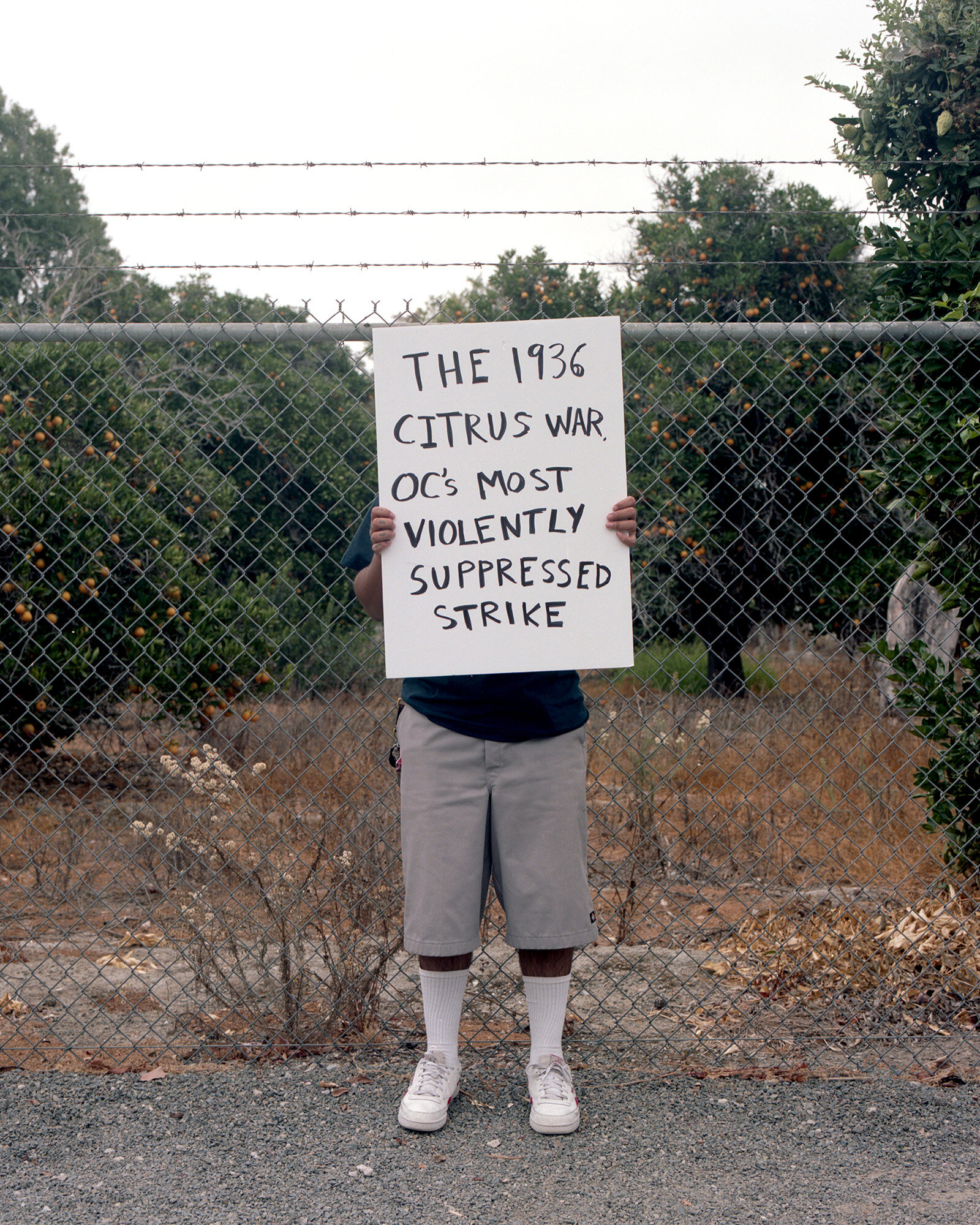

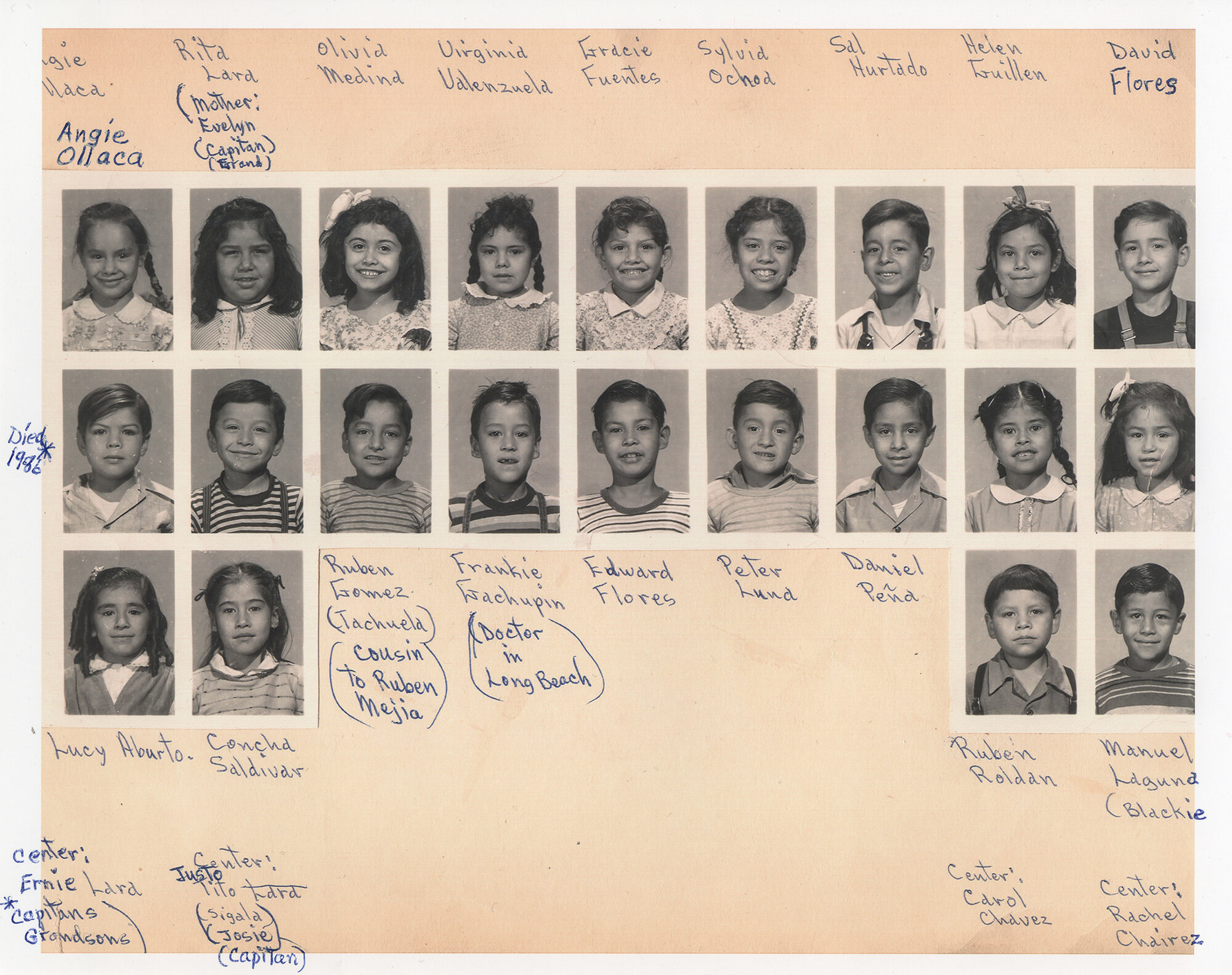

WC: I’ve always wanted to dig deep into histories, or what I would call counter-narratives. Usually, it is dealing with BIPOC communities and their erased histories that they possess. After a brief time in Chicago and learning so much about the history and liberation movements there, I thought to myself that a city where I was born and raised had these stories. The difference was that most of these histories weren’t taught to the youth and many residents were unaware of these struggles. At the beginning of my graduate studies, I decided to pursue this project. I looked through archives at local public libraries and centers that held archives. I thought about the way I was going to approach this project: it is very much influenced by Laura Aguilar’s signage work and the work of Ken Gonzales-Day. I decided I would include these moments of past histories as well as contemporary histories in the project. Those works of me holding signs in some of the places where the struggles happened were the beginnings of chapters. I also continued what I was doing since the beginning of being a photographer: documenting everyday life in Anaheim through portraits, landscapes, and street photography.

I continue to push this project, and keep digging forgotten histories of the city. Honestly, I am not sure when I will be done, it can take several years, but I love that part because that is the difference between having a deadline and working on a project like this where the work doesn’t finish. I hope to turn this into a book and am currently looking for someone to happily publish it. This was also intended to be my thesis show during grad school. Sadly, with the pandemic, it was postponed. Currently, it is showing in two different institutions in Orange County which is the first time I’ve shown my work in the county I grew up in.

Lavinia, 2018

JTD: In this work, you are interweaving the past and present, drawing a through line between racist and discriminatory practices of the past with the oppression and police brutality that is so rampant today. And, there are also elements of performance, which further call attention to the many inequalities present in our society – I’m thinking, in particular, of the image of a person standing in front of the Anaheim Sunkist Packing House holding a sign that reads “Brown women used to pack oranges here.” Can you talk to me about this blending of history and present day, and the interweaving of both photography and performance with archival and historical materials?

WC: That’s a great question. The past histories and our American characteristics of forgetting or looking in a different direction always make current histories a possibility. It is that American notion of “the past is the past, get over it” that often leads to more violence. I received mostly positive comments on that work, but also some other comments stating that white women worked there too, which I know because the image Sunkist wanted to portray was mostly white-centric. And because of that, it erased the labor Mexican and Mexican/American folx were doing in the citrus fields of Southern California. I tend to believe it is not a coincidence to connect the struggles of the past with the present. How do we end up with police violence today if it isn’t a product of lynchings in the past, and the irresponsibility to come in terms with our past affecting our current injustices? We have to look at the histories of institutions, and we can see that most of our systems in this country have a connection with white supremacy. So when I perform in front of these spaces I am already a brown body pushing back against this status quo that is white supremacy, especially knowing there was this huge presence of the KKK, and that in 2016 the KKK had a small rally in a park that use to be segregated, and that the police were dumbfounded about it but emails were brought into light that they knew about this rally and did nothing. I’m dealing, as well, with this notion of knowledge and whose knowledge is more valid. The archives are at times really hard to verify because some of these histories were only handed down through oral history or told in families and passed on like that. That made it difficult to think about epistemic oppression; performing these histories was an insertion of brown knowledge and hopefully also validates it.

Damn Ya'll Forgot Who Worked Here?, 2020

JTD: Following the thread of performance, tell me about On Performance/Intervention, a project in which you photograph yourself removing signs advertising the purchasing (and presumably, the flipping) of homes, which often leads to displacement and gentrification. When you spoke about your work recently during Filter, you spoke of the personal pain caused by these signs and their corresponding actions. Can you expand on that and tell me more about how this project came to be? What kind of responses have you received, either during the performance itself or in response to the work?

WC: A lot of my work comes from a Black feminist idea of intersectionality through lived experience. My family and several of my families were affected by the racist housing practices that happened in many Black and brown neighborhoods, the bad loans that the banks gave for a quick profit. My father who immigrated here in the late 70s always had this American dream to own a home, and when he was given two bad loans, he wasn’t aware of it, he just wanted a home for his family. Several years later he was in a big amount of debt because of those bad loans, which is very much one reason why I did this project.

An Attempt To Stop Flipping Houses, 2019- Present

The work is quite literal. It is my attempt to slow down this practice of flipping houses and gentrification. A lot of my family has been uprooted from Anaheim. I currently digitized a home video through a friend’s collective who has been working on creating a home movie archive of the Latinx diaspora, and it took me back to when birthday parties were attended by the neighborhood I grew up in and that in that neighborhood we had around 20 or more family members living within couple miles radius of our apartment. We currently have less than five families still in Anaheim.

I occasionally post an Instagram story of me taking these signs down, and I get responses from other folks in different cities stating that they also tear these signs down. It is a nationwide issue, and I believe it will only get worse after this pandemic. We are already seeing evictions skyrocket as soon as the moratoriums on rent and evictions ended.

We Gunna Have To Move Out Soon Fam, 2019

JTD: I’m interested in the Latinx Diaspora Archives, a project you created as “an attempt to elevate communities of color, those specifically of the Latinx diaspora.” Archives play such an important role in our understanding of history and culture, yet they are often unequally, and often very problematically, assembled and maintained. Or, as you mentioned, they prioritize certain types of knowledge over others. What led you to create this archive? Why did you decide to focus on family photos? How do you hope it will be put to use, either now or in the future?

WC: While I was away from home, every time I would come back, one of the first things I would do is dig into my family photos. Seeing the joy and perseverance despite many struggles brought me happiness. I wanted to see that joy more often, the counter-narrative of diasporic communities that are not often seen. During the creation of this Instagram archive account, I was influenced by ones that were already out there such as Veterans and Rucas, which is run by an amazing artist named Guadalupe Rosales. It highlights underground barrio scene in Los Angeles and other parts of southern California, but centers women of color. The Chicanx movement had a lot of misogyny and patriarchy, and @veteranasandrucas is a big counter-narrative to that. There are many other accounts that validate these other stories of BIPOC that come from those communities, which is a difference I see when we see archives and what role they play in big institutions. I don’t call myself an archivist, per se. I don’t have a master's degree in archive studies, so that is a big issue that at times invalidates my work. I would say a good amount of these amazing Instagram accounts as well are by trained archivists.

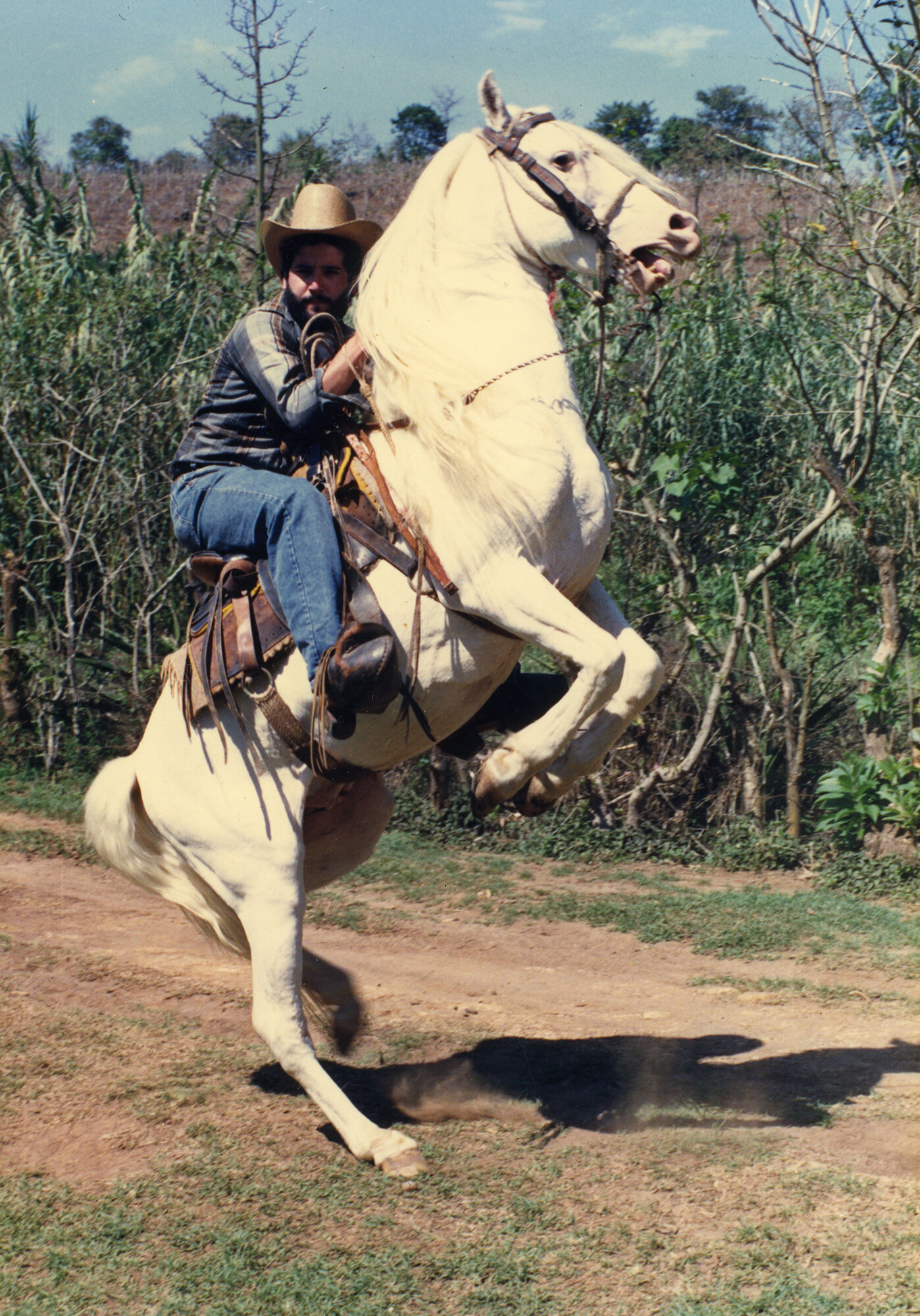

Submitted by Jennifer of her parents in from Bolivia taken in 1980, from the Latinx Diaspora Archives

I always like to think of the camera as a tool that takes us into these unseen spaces. When I think of that, I think of what Bell Hooks said in her book Art On My Mind: “The camera must have seemed a magical instrument to many of the displaced and marginalized groups, trying to carve out new destinies for themselves in the Americas.” I think about the baptism parties, the quinces, the everyday lived experiences, and those that are still less seen in Latinx culture or among Black and Indigenous folks, that are also erased in Latin America, because of the whitewashing settler-colonial states have pushed in these countries. I would love to see that get elevated. The contributions our Central American brothers and sisters have made in major cities in the U.S. are part of the story as much as any other diaspora.

I hope to start new collaborations with the many great pages that already exist, to one day house family photos in a physical space. I enjoy books and would love to see an Instagram archive book in the near future. I think about accessibility a lot as well. I want folks like my parents to view this work, to participate in collecting family photos as well. The pandemic has slowed that down, but hopefully, once this is over I can begin that process.

JTD: As you know, the mission of the Strange Fire Collective is to promote work by women, people of color, and queer and trans artists, particularly those whose work is socially and politically engaged. During your talk for Filter, you spoke about your experiences as an artist of color, in particular how you don’t often see yourself represented in museum spaces. And, of course, we are in the midst of a significant moment of reckoning for museums, galleries, and other creative institutions around issues of diversity and inclusion. How do you view your work, and your practice as a whole, in relation to formalized art institutions?

WC: Just for a little background, I didn’t step into museums until after high school. I must have been in my early-mid 20s when I first went to LACMA in Los Angeles. My parents, I think, still have not been in many and only really go when I am part of a group show at an institution. We are a working-class family and did not have that access, and when I did go, I did not really see myself in the work on the white walls, and if I did, usually it wasn’t in the work of a brown artist. I do believe the situation is changing, but museums have a long road ahead. Inclusion in spaces doesn’t necessarily mean liberation. Once we see a change in leadership, we can see some of that change. We are seeing how fragile these spaces are. When I see a director of a museum’s salary versus that of the museum workers: that is one reason these spaces are falling apart. in addition to the way they treat BIPOC folks. There is a great Instagram account called @changethemuseum and it has stories that are not surprising to me, but that show how leadership is really naive about race. I see them as racist institutions.

I have been surprised by my work having some spotlight currently, but I believe that the conversations my work produces are relevant in this moment. The notion of rethinking the canon, especially in photography, is a big challenge, but one that I want to take on, and along with that, to look at how BIPOC folks’ work is seen in museum spaces. Despite being a first-generation college student, I do have the privilege of being educated in institutions and I now have an MFA. I am using the tools I learned there and finding ways to deconstruct these spaces.

JTD: Talk to me about this moment we’re in: how are you holding up? In what ways do you feel that the pandemic has affected your work, if at all?

WC: Thankfully, I am doing better now. The first couple of months were tough, and it is still tough, but I have been lucky to be able to work from home at times. I am more worried about my parents who are working long hours because they are “essential workers”. I put that in quotes because they are being uplifted right now, but they still make minimum wage, and they don’t have that luxury to work from home.

As for my work, it has taken me back to this Chicanx framework of rasquache, which in Chicanx art history was written by the amazing Tomas Ybarra Frausto: to be rasquache is to be resourceful, to make do with what you got. Something that many working-class folks have been doing for a long time. That’s how the series All That I Can Carry came about. I used what I had around, which is why I am carrying what I am into those new works.

JTD: And last, what are you currently working on? What’s on the horizon for you as an artist?

WC: I'm thankful to be in a couple of shows in the next few years: one at the Center for Photography at Woodstock, Forecast 2020 at SF Camerawork, and one in 2022 which is a look at Chicanx Art from the 1970s to the present. I hope to keep showing my work around the country and to one day publish my Origins and Displacement project as a book.

I am also very excited to be the artist in residence at the Latinx Project at NYU and am thankful for the folx at that space to give me this opportunity (shoutout to Arlene Davila who just came out with a book on Latinx Art). I will hopefully one day celebrate my MFA, that I finished this past summer. I’m thankful to my committee and Ken Gonzales-Day, too. And, of course, I’m thankful to my dear parents for their support in my endeavor to be an artist.

JTD: Great, thanks so much William!

All images © William Camargo