Q&A: Thomas Locke Hobbs

By Rafael Soldi | October 12, 2017

Thomas Locke Hobbs studied at the Talleres de Estética Fotográfica led by Eduardo Gil in Buenos Aires, Argentina between 2009 and 2011. In 2015 he received an MFA from Arizona State University. He has exhibited work in Buenos Aires, Lima, London and Phoenix, Arizona. He currently lives in Los Angeles, California.

Rafael Soldi: What was your path to photography?

Thomas Locke Hobbs: I was a long-time hobbyist and gallery-goer. I lived in New York City from 2001 to 2005 and had the chance to see a lot of really incredible shows. I remember being particularly impressed by the Thomas Struth show at the Met in 2003. I moved to Argentina in 2008 and it was there that I started studying photography more formally, first at the Centro Cultural Rojas with Alberto Goldenstein and then later in the private talleres (workshops) of Eduardo Gil and Ignacio Iasparra. Studying with them was transformational for my practice. Having them as role models as photographers and artists gave shape to my own desires and aspirations. Honestly I don’t know why I didn’t take classes sooner.

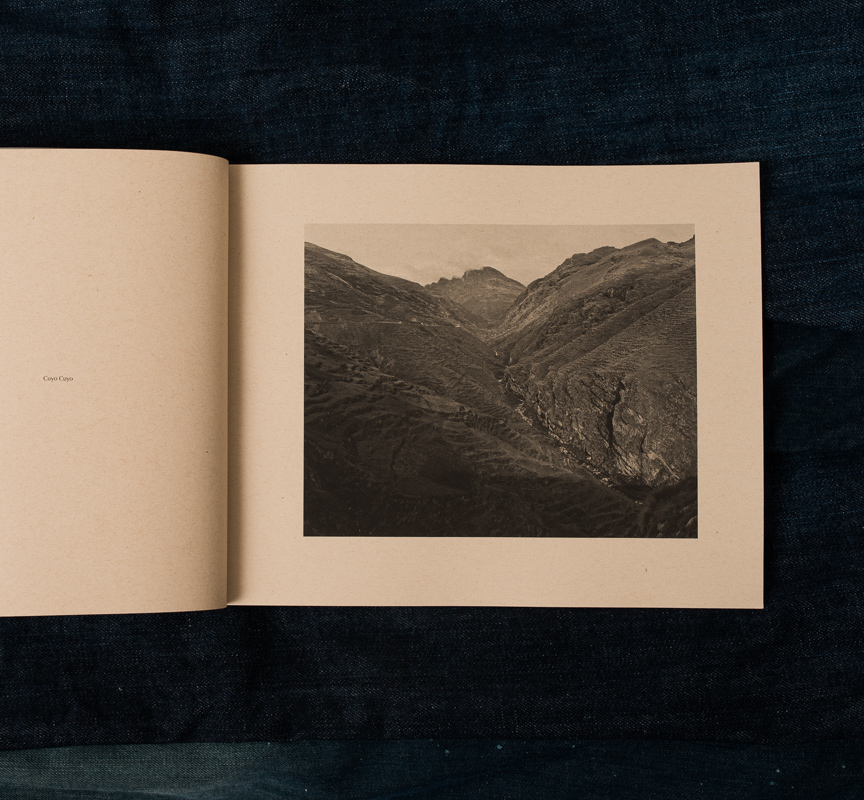

From Barranca

RS: Travel has been a huge part of your practice, and you've made work in South America for a large part of your career. You've made work in places from Argentina to Peru, often photographing very different subjects, from urban surveys to portraits of queer men. What drew you to this part of the world?

TLH: I was drawn to Buenos Aires for personal reasons. I was in an intimate relationship with someone there and that eventually lead to me photographing my surroundings there. It was only after I broke up with my boyfriend in 2010 that I really started photographing seriously. I had lots of ideas but I had always been afraid of going out on the street and having my gear stolen. Suddenly with a lot more free time, my desire overcame my fear and I started working on five separate projects more or less simultaneously. Those first projects were about trying to understand and analyze the city I was living in as a single, gay, foreigner.

RS: Much of your work explores how human intervention has shaped the landscape and its social context. Several of your projects explore the topography of both landscape-turned-city, and city-turned-landscape. Can you expand on this?

TLH: Around 2008/2009 I was discovering the work of Lewis Baltz and other photographers related to the New Topographics exhibition in 1975. I really responded to their cool, systematic way of seeing. A lot of that work deals with a critique of our relationship with the landscape and the various ways that social and political forces get expressed in the built environment. If anything, these issues seemed even more pertinent in South America where the scars of colonialism and the ongoing depredations of capitalism are very much on the surface.

RS: A big part of your process is typologies, Ochava Solstice, Pulmones, Chalet Porteño, and even Some Guys all include systematic repetition or organized pattern. What about this strategy do you find appealing, how do you feel it helps you present the information you're choosing to photograph?

TLH: For an example of what I mean by the scars of capitalism, my project Ochava Solstice looks at apartment buildings made in the 1960s when Argentina endured a number of military coups and the beginnings of hyper-inflation. One of the responses of the middle class was to put their savings in real estate as buildings are harder to expropriate than bank accounts. A bland, functional aesthetic resulted from buyers interested only in square meters. A quirk in the zoning law required the ground floor, but only the ground floor, to have a diagonal cut to aid visibility at intersections. All other floors were built to the zoning envelope, that is a right angle corner. The result is an triangular shadow that tracks the motion and heigh of the sun throughout the day. I kept seeing it in my walks around the city like an unintentional calendario porteño. These buildings are literally everywhere in Buenos Aires, altho it took a lot of searching to find the most ideal examples. I photographed these buildings with a 4x5 inch camera and would wait for the precise minute the shadow formed an isosceles triangle. At first I thought I would stop at ten but then the quantity became important as it indicated that this was a social phenomenon and not simply an odd site. I spent two years searching and the final series has 49 photographs of different buildings, with the first and last photographs being of the same building in different seasons.

From Ochava Solstice

You might be getting the sense by now that I’m a little obsessive, which is maybe a better, more accurate response to your question. My other projects in Buenos Aires were similar attempts to use repetition to make a statement about something I was observing. Chalet Porteño looks at Swiss-style “chalets” which are built in the middle of the city and questions why such an out-of-place style of house is desirable, Pulmones looks at private landscapes within city blocks, and Some Guys attempts to visually superimpose the men I was meeting upon the color and texture of the city’s architecture. Another project, Riverbank | Barranca, is not a typology but uses the format of the photographic survey, in this case photographing from the one topographic feature in an otherwise very flat city, as a way of looking at the city’s history. Each of these five projects in Buenos Aires is a kind of axis for looking at the city and understanding a certain part of it. While I think each project has its merits individually, I’m also interested in how they function as a group as a way of painting a sort of personal/analytical portrait of the city.

From Chalet Porteño

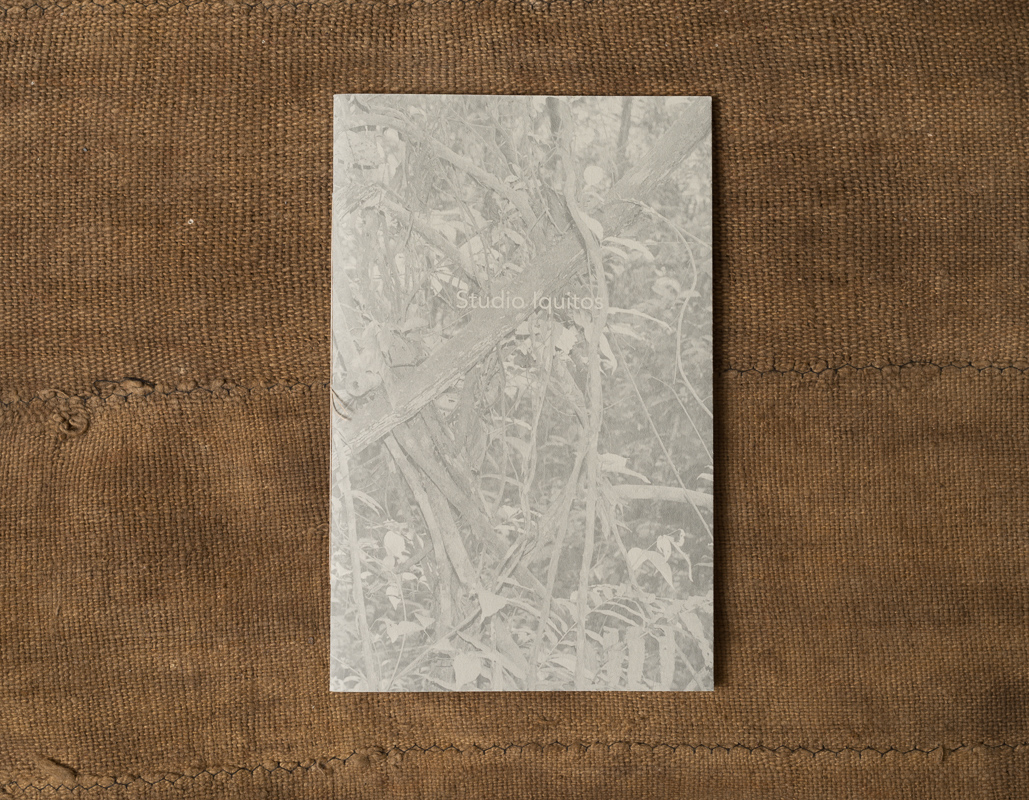

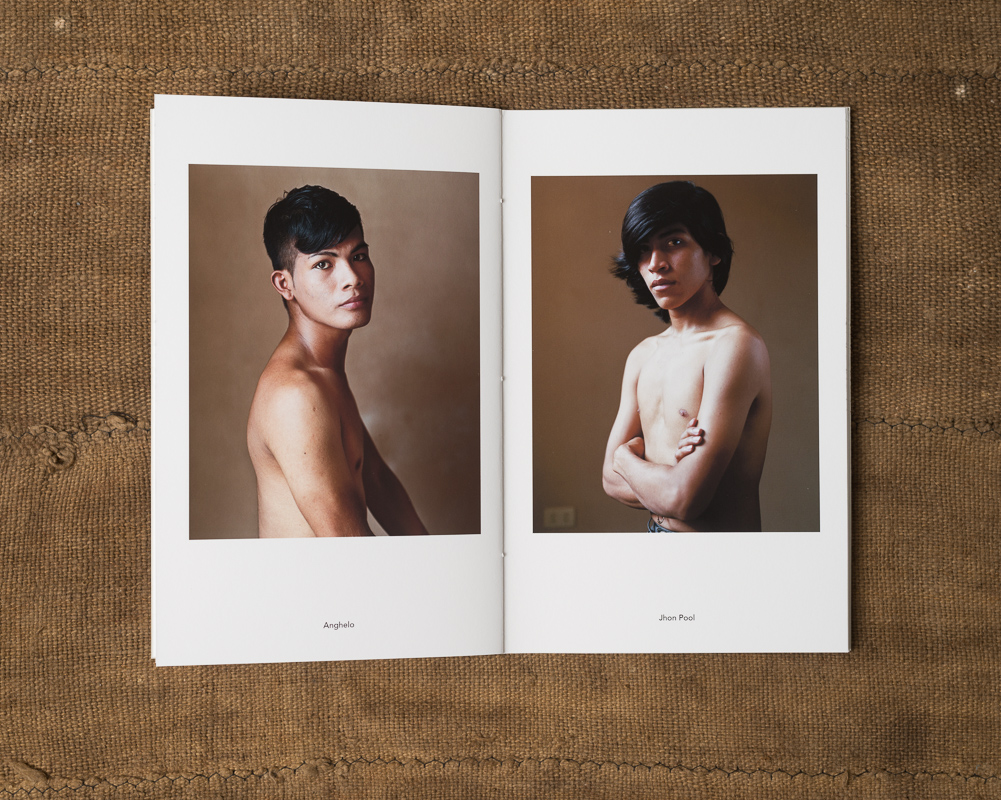

RS: Your body of work Maravilla del Mundo depicts young gay men in the city of Iquitos, in the Peruvian Amazon rainforest. I was born and raised in the coast of Peru, and as a gay man I'm acutely aware of how taboo the subject can be in that country. Growing up homosexuality was not something we discussed openly. The city of Iquitos, however, has a different relationship to the LGBTQ community, and you as a white foreigner have a certain carte blanche to make this type of work. How did you land in Iquitos, what drew you to complete this project, and what do you see your role being in the telling of this story?

TLH: This is a project I have now spent seven years working on. I first went to Iquitos in 2011 and have returned annually since then, schlepping my 8x10 and usually spending a month there, often photographing the same people repeatedly over different trips. While I was still living in Buenos Aires and making portraits for my Some Guys project, I realized that I was meeting and photographing a lot of men from Peru. There’s a very large immigrant community of Peruvians in Argentina and I think that first got me thinking about traveling there. Also, sometime during 2010, I came across an image in a catalog of recent Latin American Painting of “La Orilla” by Christian Bendayán, a Peruvian painter from Iquitos. The painting depicts a young man who is half-man/half-pink dolphin, a sort of fabulous queer merman. I had never seen a picture like this before and I wanted nothing more than to go to there, find this beautiful young man and photograph him.

La Orilla by Christian Bendayán

The culture of Iquitos and the Amazonian region of Peru is very different from that of the coast and highlands, as you mentioned. Queer people in the Amazon are often subject to discrimination, violence and prejudice but there is a visibility present that is almost entirely lacking elsewhere in Peru, outside of the capital. As a practical matter, as a photographer, I’m limited to what can be seen/shown and who is willing to pose for my camera. I found in Iquitos a great enthusiasm for being seen and pictured.

The title of the work, Maravilla del Mundo, which means Wonder of the World in Spanish, refers to the Amazon River as well as a specific incident in 2013. There was an online campaign to elect the new seven natural wonders of the world. It was being run by some NGO in Europe but the city leaders of Iquitos put a lot of effort into marketing the online voting locally. When the Amazon River was selected as one of the winners of this online poll, the people of the city were very happy and a metal plaque was erected to commemorate the occasion. The results were used in promotional materials for marketing tourism. Meanwhile, much of the city suffers from chronic annual flooding and drainage projects are perpetually stalled amid allegations of official corruption. The whole celebration seemed to me like a diversion from more pressing issues. Nevertheless people were very proud and happy to identify with something larger than themselves and their immediate reality.

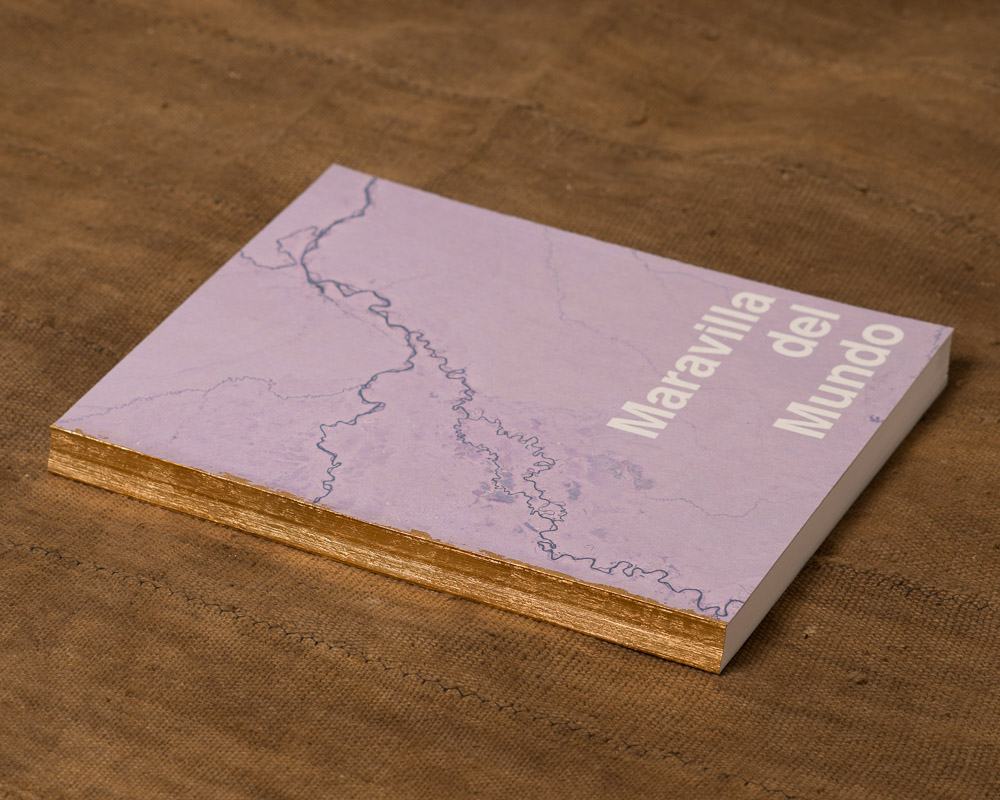

Maravilla del Mundo installation at Buffeo

This struck me as an apt metaphor for the contradictions present in my own photographs. Here I was seeking out photographic beauty in a place of poverty. To not acknowledge this complicated social and economic reality is to indulge in a colonial fantasy. At the same time, however, there is a great desire for visibility expressed at both a personal and societal level. Exotic tropes are used as marketing ploys to attract tourists but then also become part of the regional culture and identity. I was interested in this mix of reality and attempted fantasy and the way they intermingled in my photographs.

My privilege as an outsider and the resulting dynamic between me and those who I am photographing has been a foundational component in making this work. I felt it would have been dishonest to put up a façade of journalistic distance and objectivity, hence the inclusion of the photograph of myself, gazing at the subject gazing back at me. I wanted to make explicit this dynamic as I think it’s already implied in many other photographs in the series. My goal has been to make a work that is complex and nuanced, that shows aspects of the reality of this place as well as my own subjective view of it.

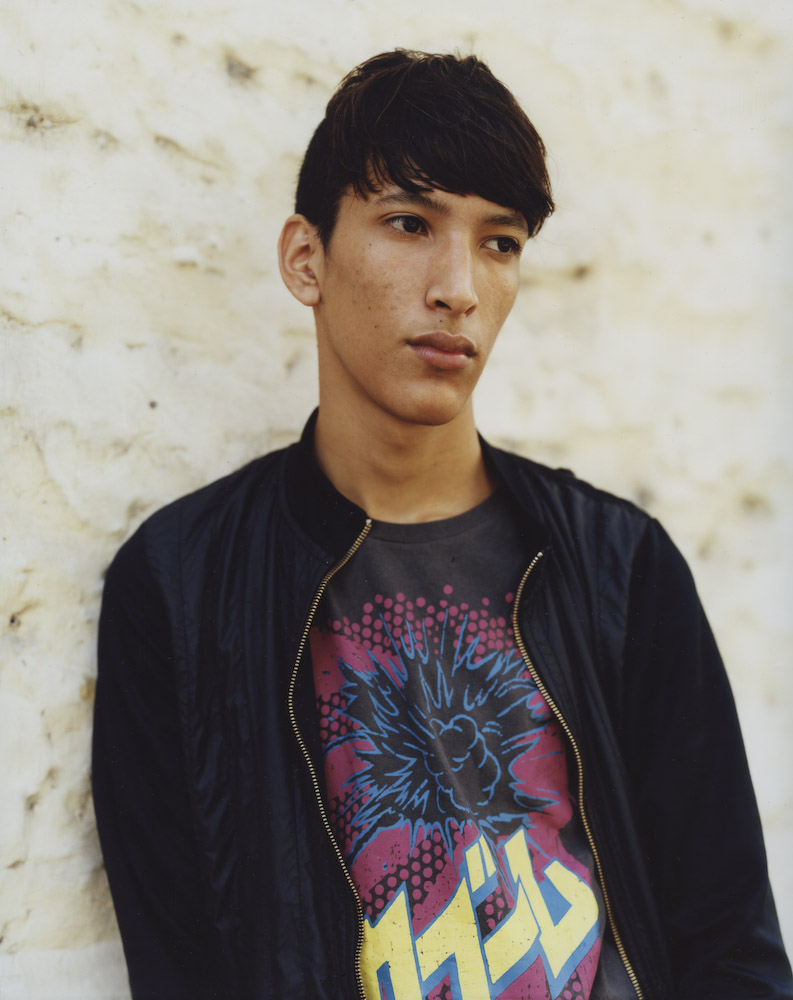

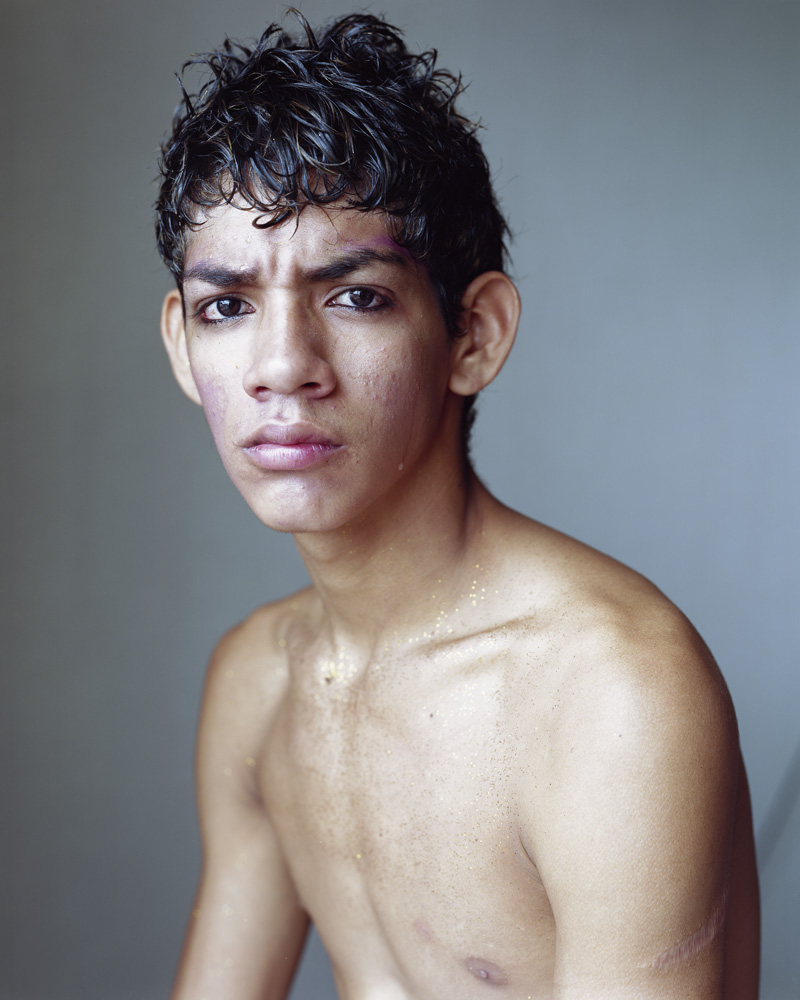

From Maravilla del Mundo

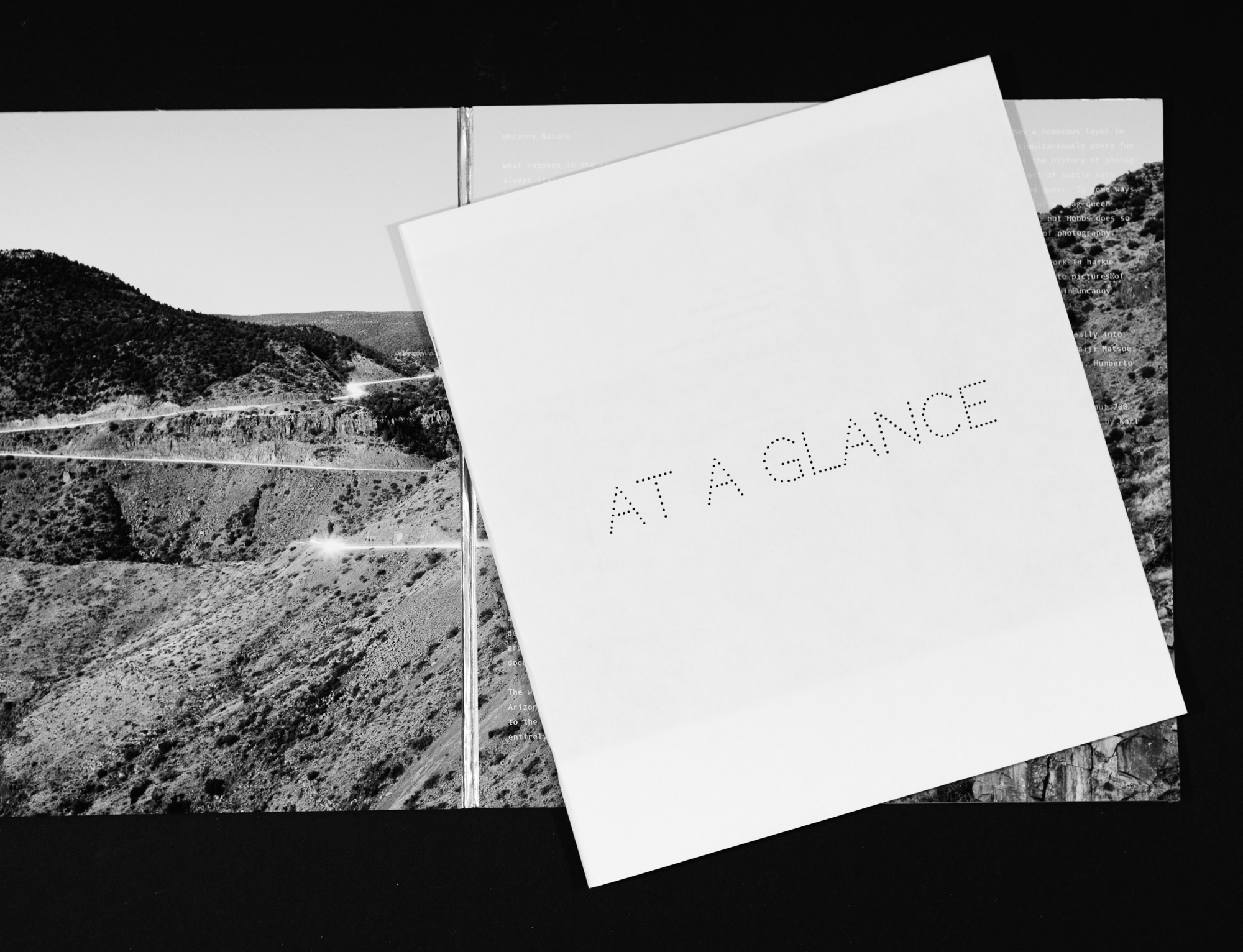

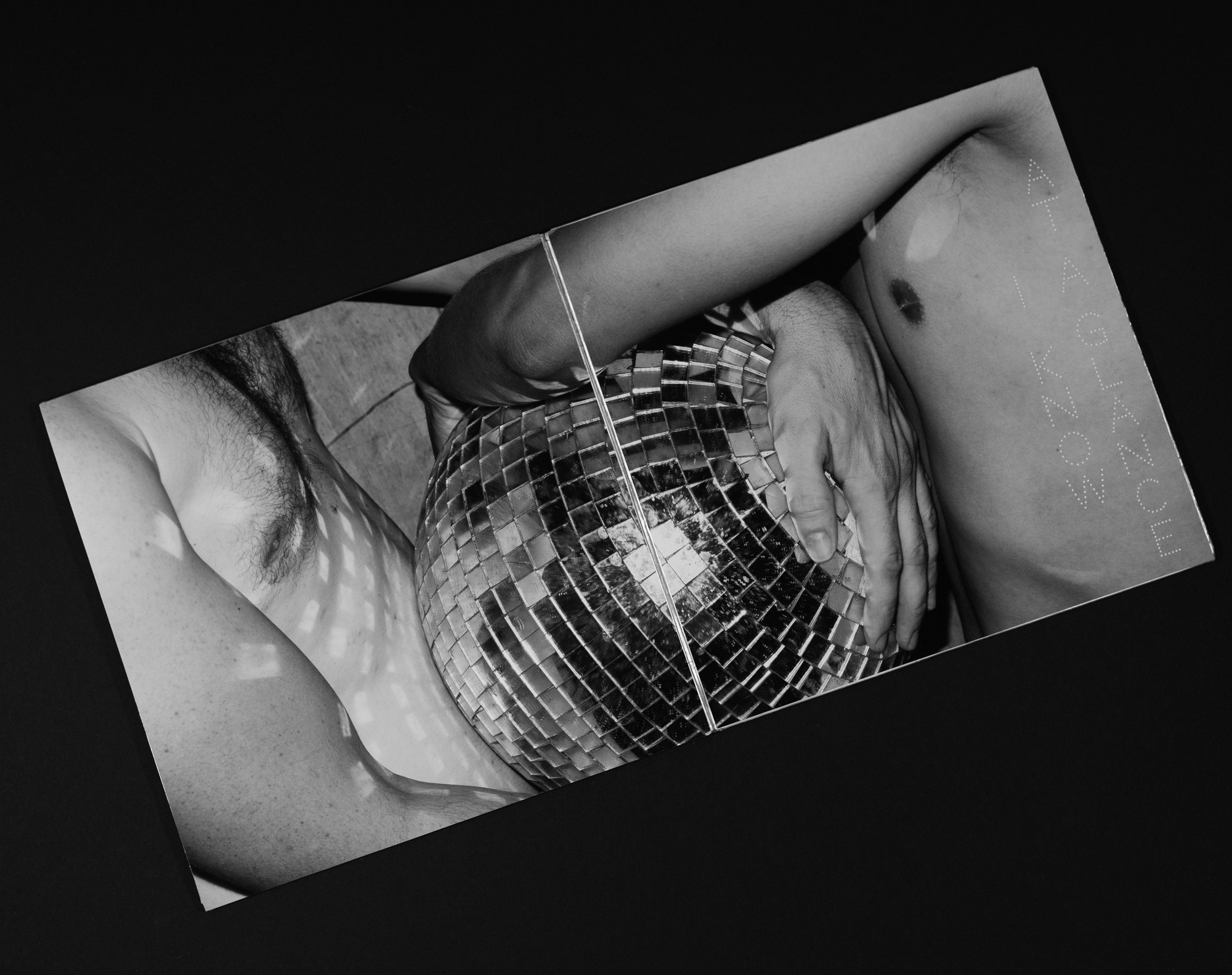

RS: In I Know at a Glance I see echoes and references of your earlier work, but to me the work feels like a departure—your shooting and editing style here feels much looser. Do you agree? How do you think graduate school changed or challenged, if at all, your way of working?

TLH: I’ve always made photographs that aren’t part of whatever project I think I’m working on. I wanted some way of bringing these images together and to make something more allusive and lyrical. I returned to the US in 2012 to attend graduate school at Arizona State University in Phoenix. There’s a long tradition of craft in photography in Arizona and I was able to immerse myself in library books, make prints in my own darkroom, and see Frederick Sommer contact prints at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson. I was inspired by this history but also a little annoyed by its limitations as a lot of it is heteronormative and dull. I was seduced by the craft but put-off by the macho swagger and pseudo-mysticism. I wanted to use the aesthetic specifics of the medium, in a sort of old-fashioned modernist way, but apply it to a contemporary subject matter that related to myself as a queer individual living a sprawling metropolis in a red state in the early teens.

From I know at a glance

Going back to my being influenced by the New Topographics exhibition which was originally shown in 1975, I was thinking a lot about how I was making work roughly forty years later, which was the same amount of time that separated that exhibition from Walker Evans’ work in the Great Depression. I was wondering what a post-New Topographics approach to photography of the built environment might look like, especially now that a couple of generations have passed. I got to thinking about some of my photographs as lyrical responses to the built-environment that we’re still living in 40 years later. I see them as less about analysis than about poetics and my own identity in a certain place, this time the American Southwest. I had the great fortune of studying with Bill Jenkins, who curated the original New Topograhics exhibition and who helped open up for me the poetic possibilities of photography. I also owe great deal of credit to the other students in the program for their feedback and support.

From I know at a glance

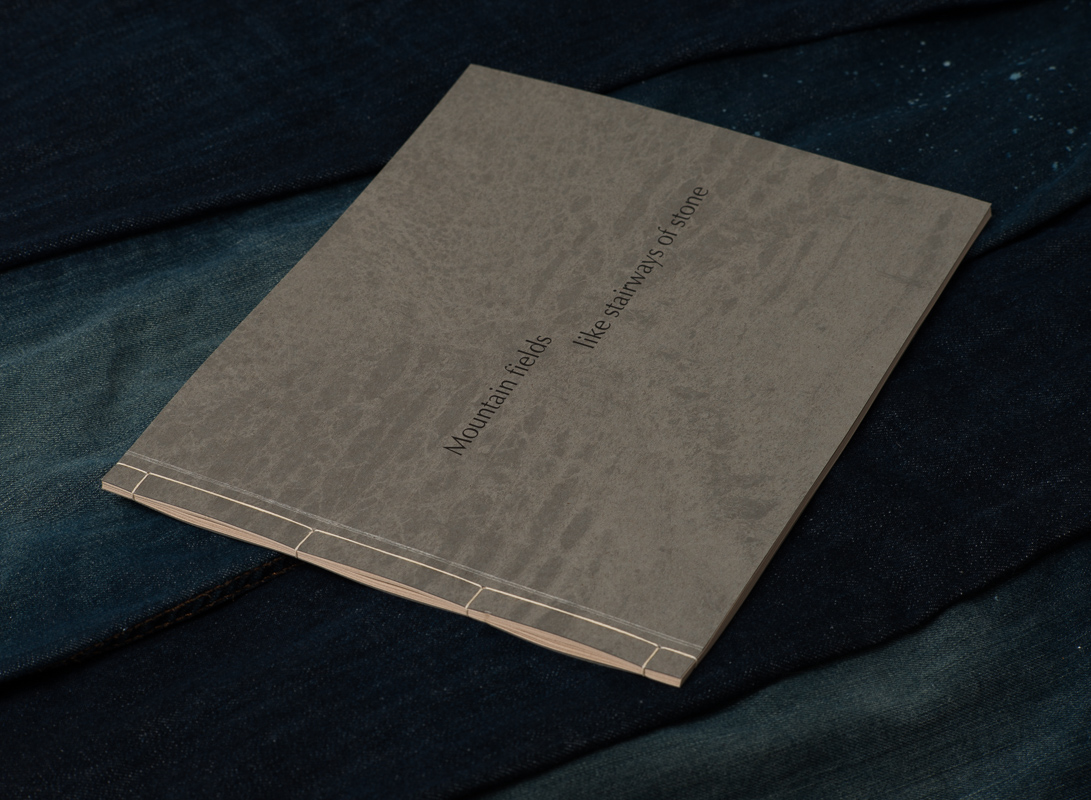

RS: Last but not least, books! You make beautiful artist books. Tell us what you love about them and how we can get our hands on them.

TLH: I love photo books! Photographs are malleable. They can be made to fit any size or context. Books are one of the best containers for their durability and portability. I’m interested in how the craft of the book object and the selection and ordering of the photos can help construct and influence meaning. I’ve made a couple of small edition, hand-made artist books that I’m selling, mostly as a way to get my feet wet for bigger book projects I’d like to make further down the line. One is called Studio Iquitos and is a subset of portraits from my larger body of work from Iquitos and the other is called Mountain fields like stairways of stone which looks at human-altered landscapes in Peru from a thousand years ago and contrasts them with the modern, informal urban landscape in Lima and other cities there. Since they’re small editions I’m selling them both directly. Anyone who is interested in them should contact me directly.

I have also been working on fairly elaborate book dummies for Maravilla del Mundo and I know at a glance, both of which I hope to eventually to publish in a larger trade edition. I have to confess, my craft is pretty mediocre and a lot of what I know is self-taught. I like using book dummies as a vehicle for presenting the work (as opposed to a portfolio). It can show a greater level of intentionality and is often a lot more engaging for the viewer. I think the book format is a great way to engage with the viewer directly and talk about these issues of queerness, urban architecture and landscape that I’m interested in. I’ve made work over a pretty wide geographical space and I want the opportunity for audiences there (and elsewhere) to be able to see and enjoy it.