Q&A: The High Wall: Kei Ito

By Jesse Egner and Kelly Lee Webeck | August 4, 2022

Kei Ito is a visual artist working primarily with camera-less photography and installation art who is currently teaching at the International Center of Photography (ICP). Ito received his BFA from Rochester Institute of Technology and MFA from Maryland Institute College of Art.

By excavating and uncovering hidden histories connected to his own, Ito utilizes his generational past to use as a case study for contemporary and future events. Many of Ito’s artworks transform both art and non-art spaces into temporal monuments that became platforms for the audience to explore social issues and the memorials dedicated to the losses suffered from the consequences of those issues. Within these intertwined pasts, Ito shines a light on power and its relationship to larger global issues that often lead to and result in both war and peace alike.

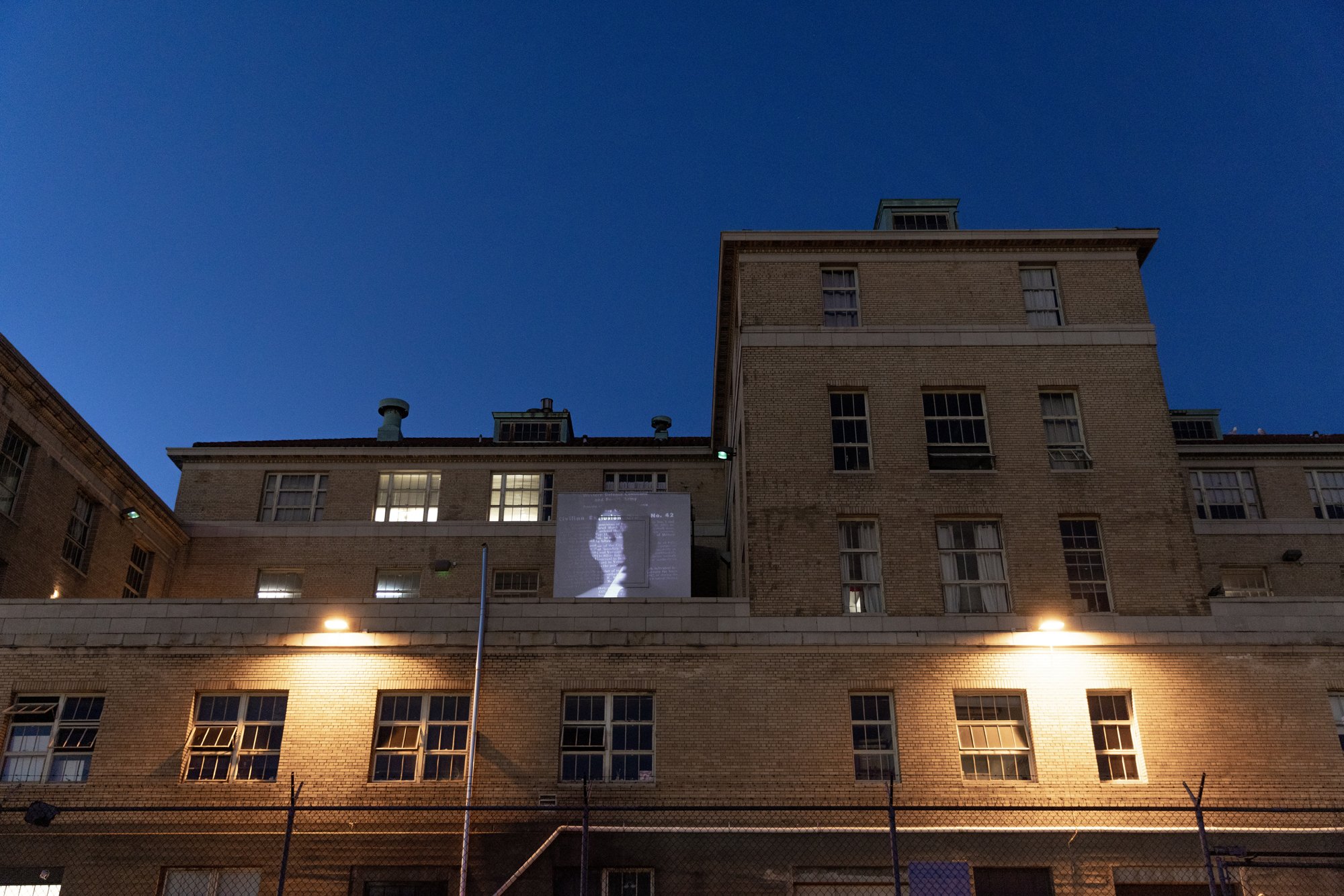

The High Wall 2022—in partnership with Strange Fire Collective— presents three video works to be projected on the facade of the Inscape Arts Building in Seattle, WA. Inscape resides in a former immigration detention center; because of the building’s history we have selected artists whose work explore broad ideas of immigration, diaspora, and borderlands. We are proud to have chosen Kei Ito, Brandon Tho Harris, and Julie Lee - three artists who examine these themes through the use of photography and the moving image. Although each piece is presented as a video, the artists each utilize the medium and materiality of still photography. Photograms, a vernacular family photo archive, and glitched google map images each make connections about migration, place, community, family, and home.

Kelly Lee Webeck + Jesse Egner: Hello Kei! We are both so happy to welcome you back to Strange Fire Collective and thrilled that we were able to include your work in The High Wall 2022 exhibition. We recognize that place is incredibly important to your artistic practice and you are very conscious of the history of a location when you choose to show your work there. Why do you feel that the Inscape Building, where The High Wall exhibition is being shown, is the right location to show “Hymn for a Lost Tomorrow”?

Kei Ito: Many of my artworks transform both art and non-art space into an environment that reflects the idea of memorials and monuments. I think about the historical importance of the land, architecture and institution to add meaning for installation-based artwork. As a recent immigrant coming from Japan, the history of Japanese Internment and how it relates to today’s political turmoil is something that is always in the forefront of my mind. Thus, this artwork which is projected on a location where Japanese and Japanese Americans were imprisoned before they were sent to a Japanese Internment Camp uncovers and visualizes the hidden trauma embedded in the building.

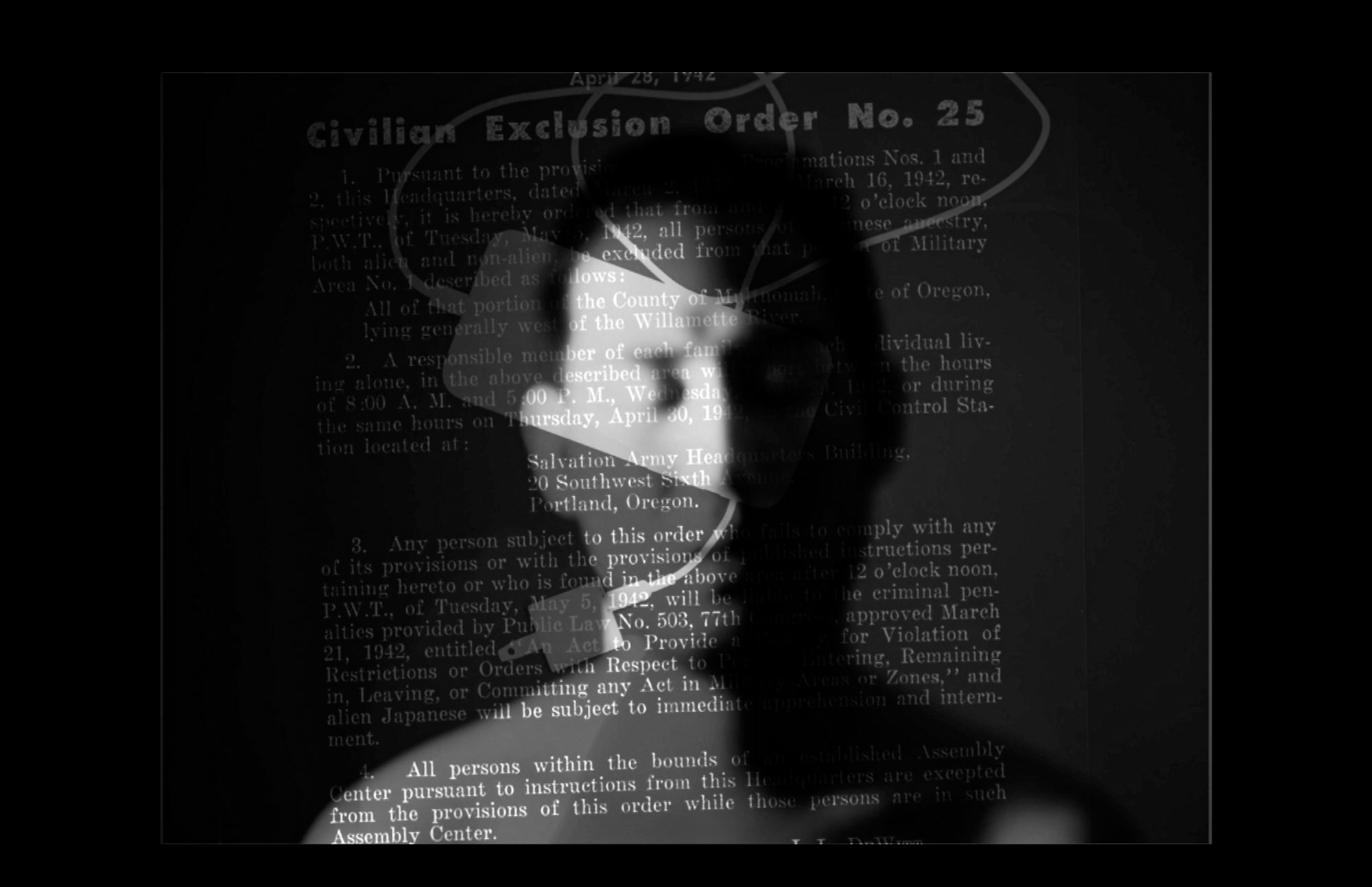

Hymn for a Lost Tomorrow, 2022

KW + JE: How did “Hymn for a Lost Tomorrow” come to be?

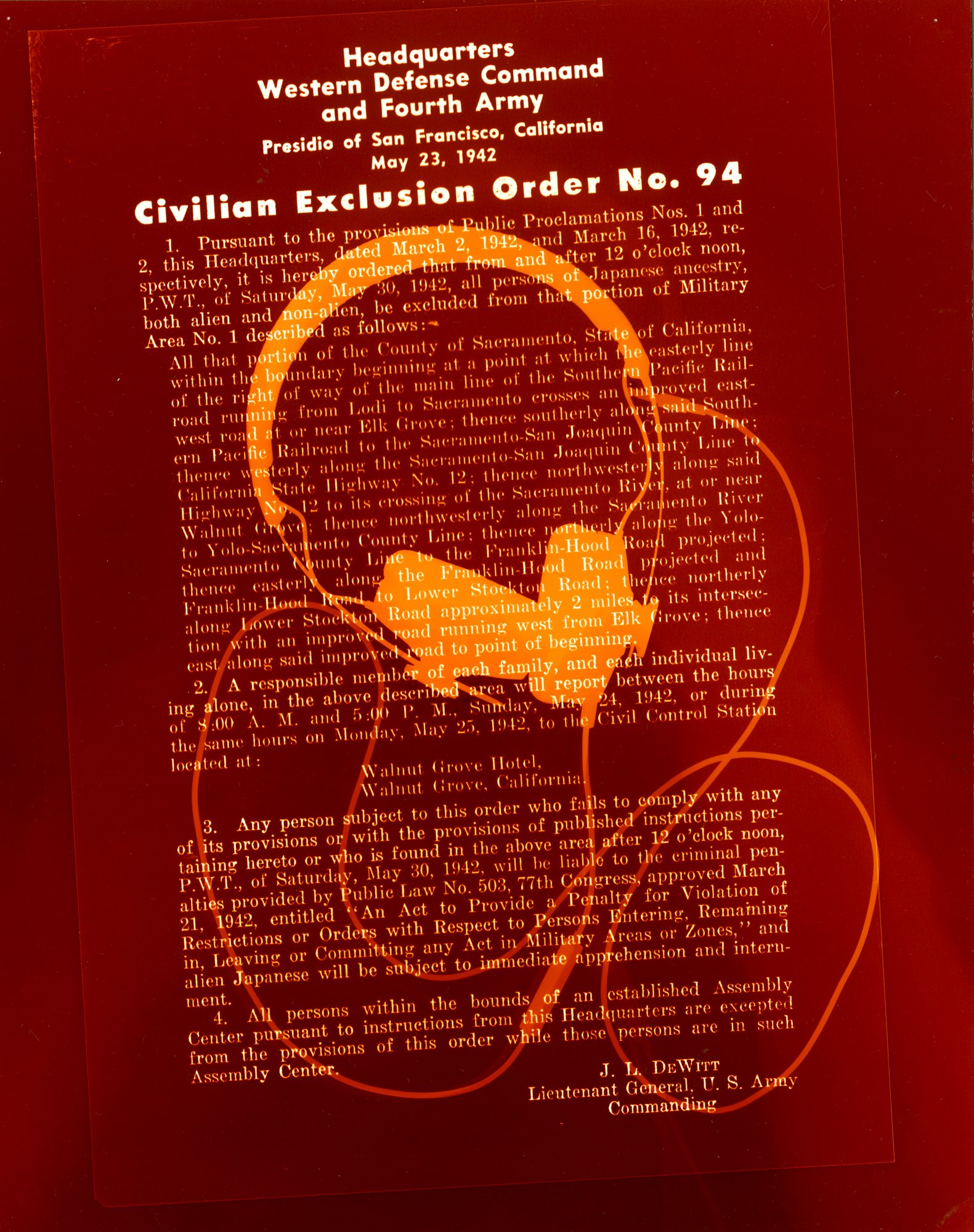

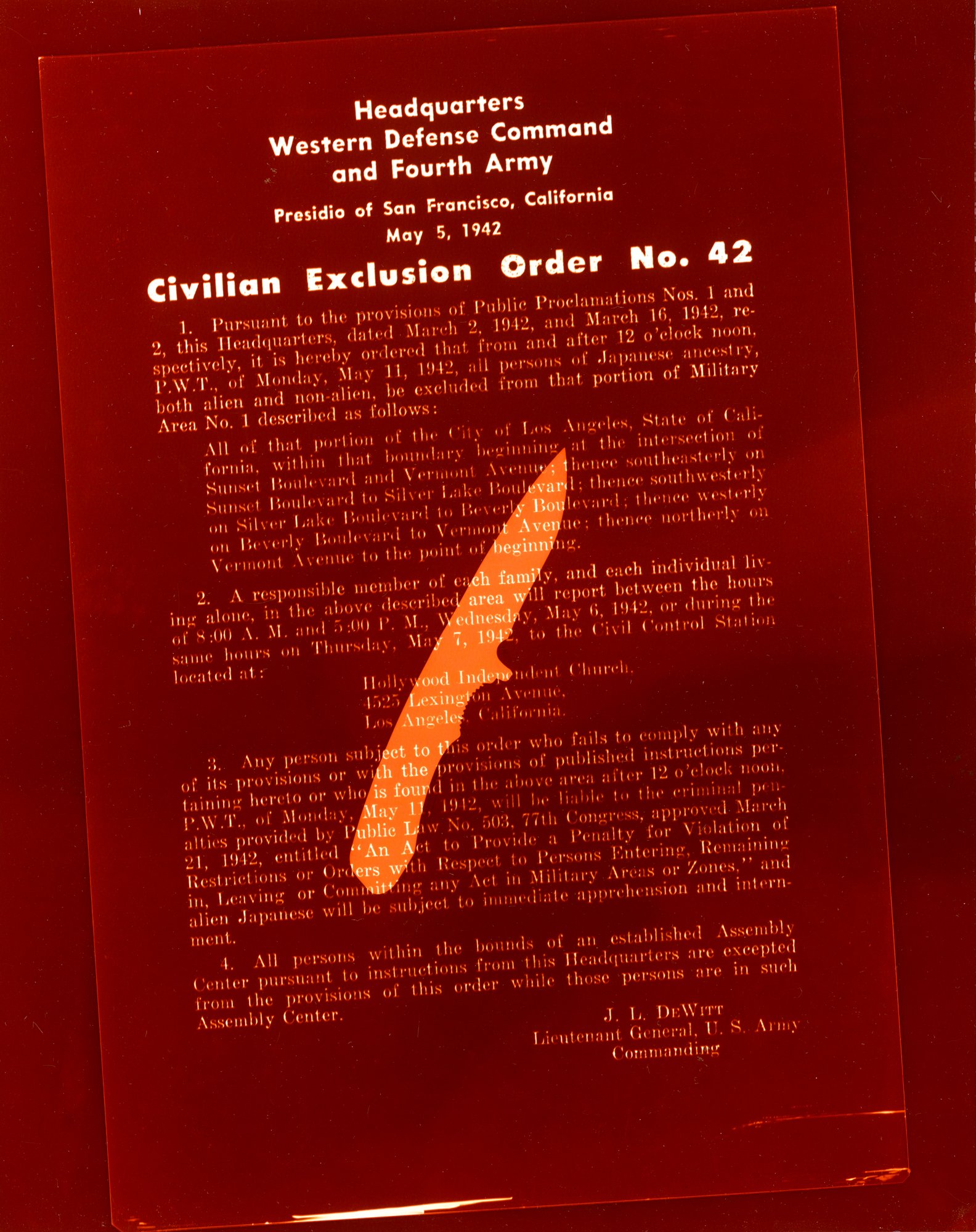

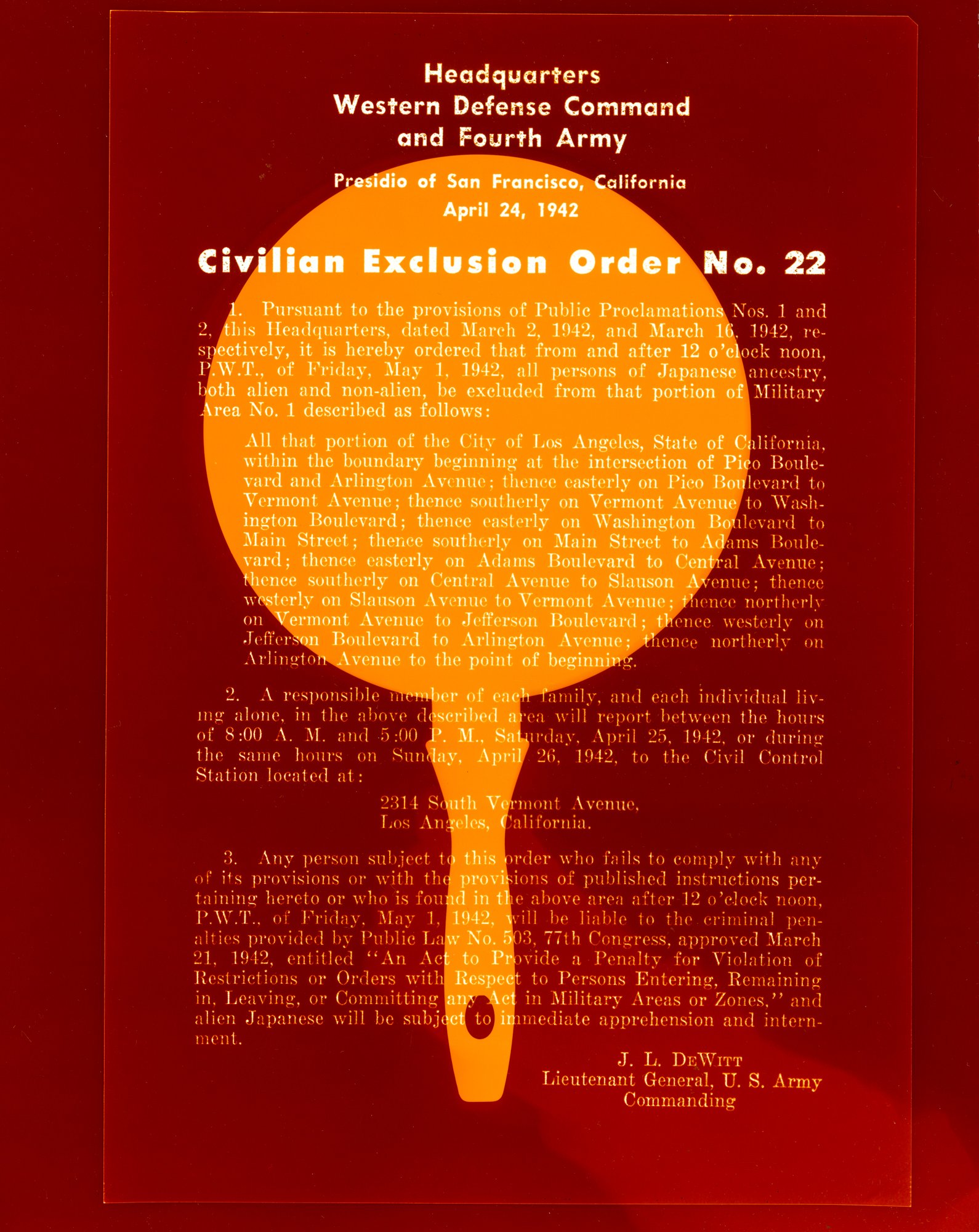

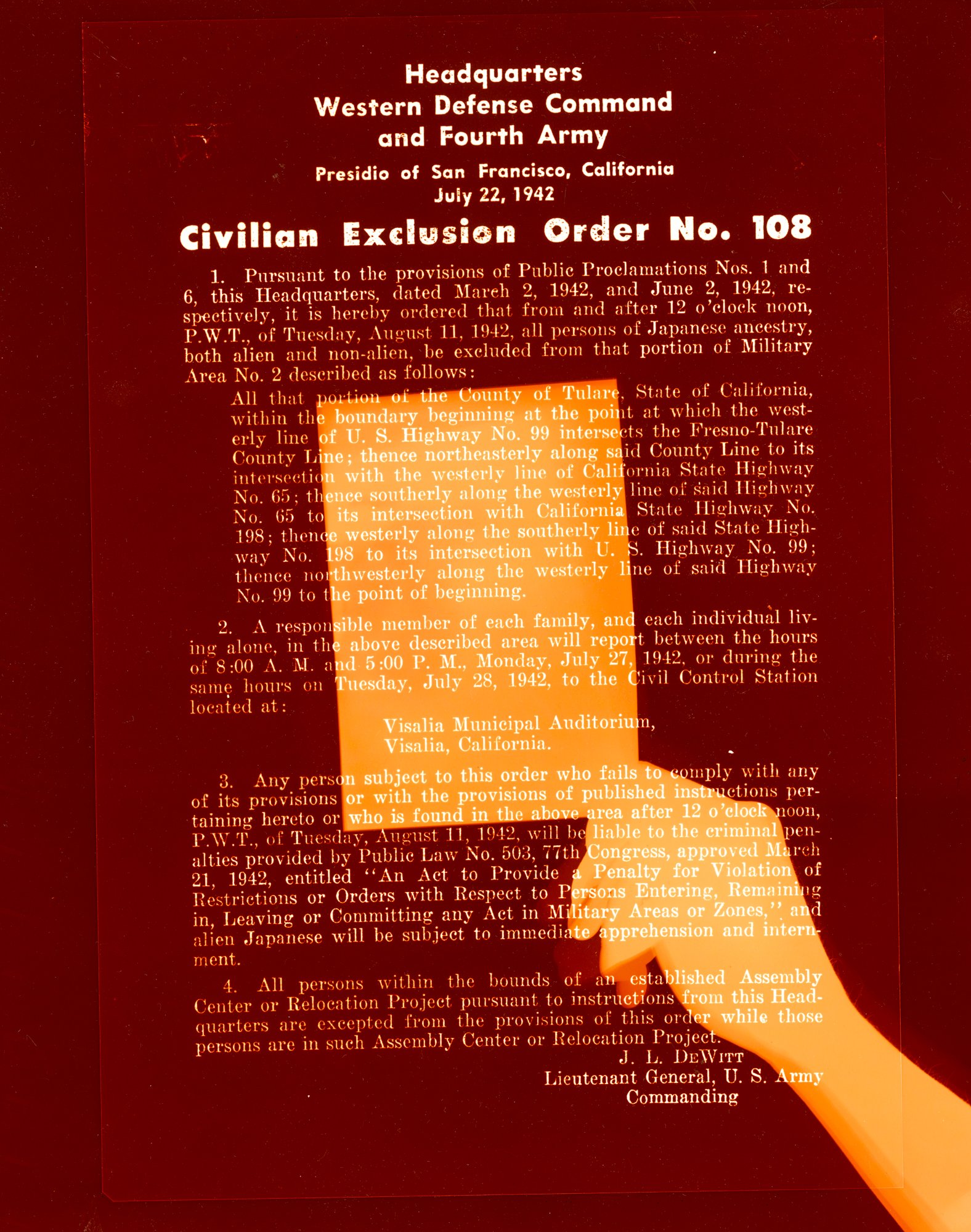

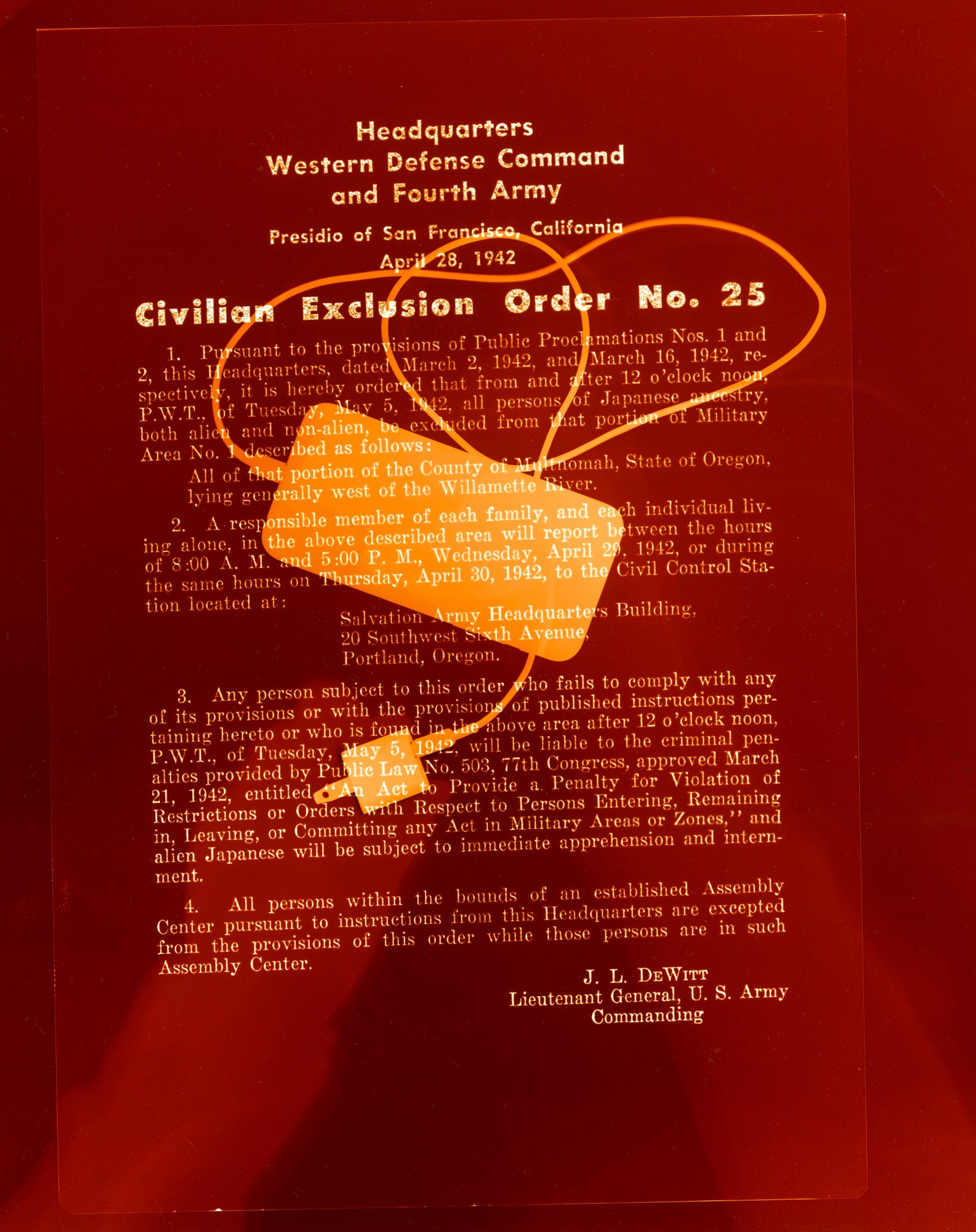

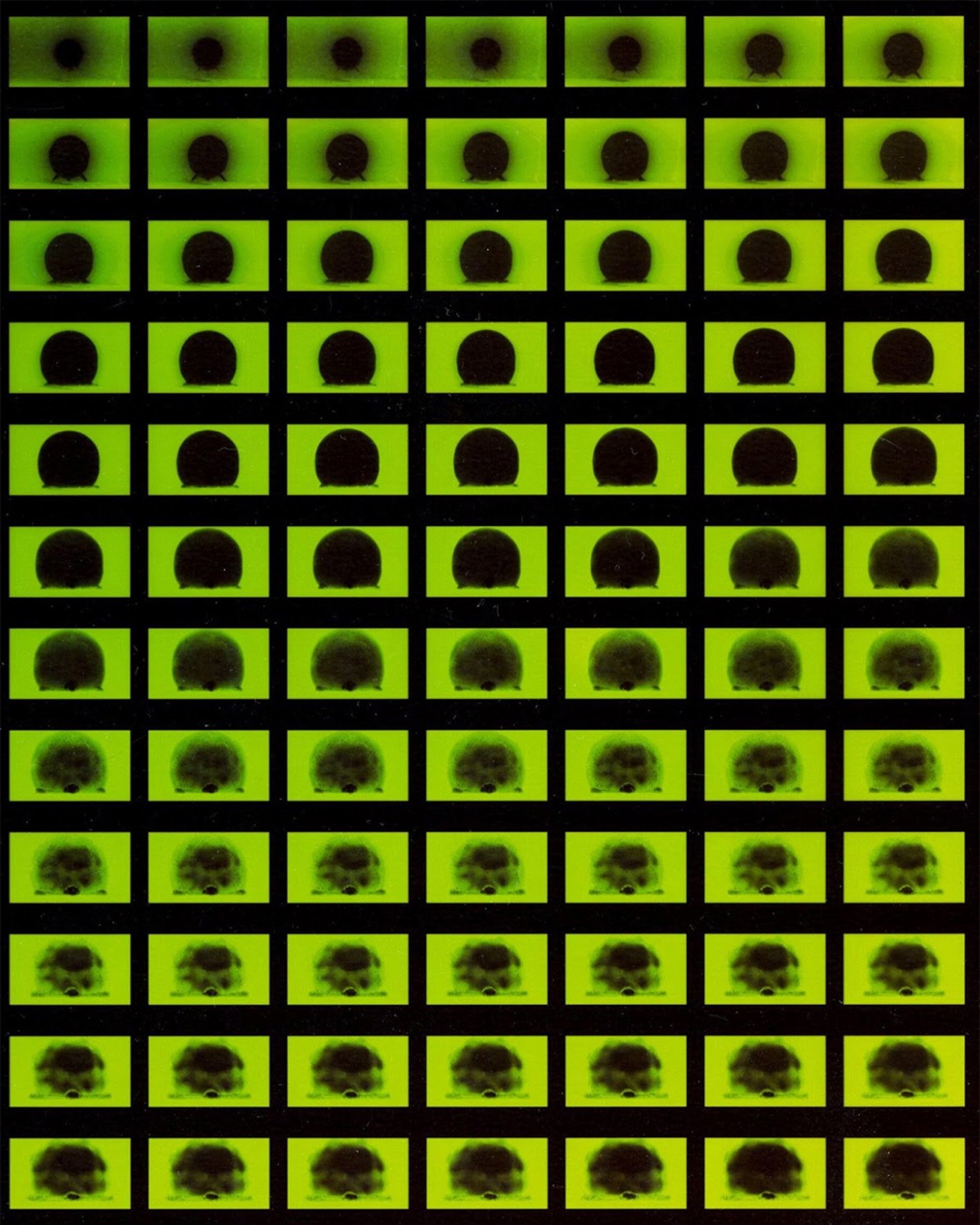

KI: The video is based on a project I created in 2017, a series of photographic artworks called “Only What We Can Carry” in response to the Muslim Ban. It consists of around 100 contact C-Prints of Japanese Internment Camp (Civilian Exclusion Orders) posters exposed with various everyday objects. These everyday objects represent what I would bring with me if I had one day to gather my belongings. This poster became a symbol of bigotry and paranoia towards a specific group of people, and it echoes in these times where these same prejudices have reemerged for another group of people. Denial and misjudgment led by blinded authority is a phenomenon close to what we have been witnessing in recent political climates.

I believe that artworks should be fluid and adaptable, meaning that when you create an artwork, it is never truly complete. Rather, later on they take different additions, forms, contexts, etc. “Hymn for a Lost Tomorrow” is an example of this. I revisited “Only What We Could Carry” and used the prints to create a video piece which presents me in front of the prints singing a silent hymn and contemplating on past traumas as a singing siren warning the future.

Hymn for a Lost Tomorrow, video still, 2022

KW + JE: Tell us about your research process. How did you come to find the archival documents that were used? Can you tell us about some of the specific objects you chose to include in the photograms?

KI: I generally search for digital archives in university libraries that have special collections related to the topic. Unfortunately, many of these institutes who have relevant collections may not have accessible digital copies of these objects and documents. So, I have to physically have access to the space to make these projects happen. I was fortunate for this project that the internment camp posters were easier to gather in my research. As for the objects, I filled two bags full of items I would gather to take with me to a modern day internment camp if I was to be detained by the government as many others were at the time. Some objects are banal and everyday like my toothbrush or a frying pan. Some were more intimate, such as family photographs, my favorite book, and some are more contemporary objects such as my laptop, cell phone, or their accompanying chargers. Where in the past the items gathered by those who were interned were a mixture of personal and cultural items, today, the things I packed would be reflected in a larger majority.

Hymn for a Lost Tomorrow: video still, 2022

KW + JE: You work predominantly with cameraless photographic processes and the physicality of the object seems incredibly important in many of your projects. What is your relationship to the medium of photography?

KI: For me, photography is not just a camera but rather the capturing of light. When I first started making work centered around my heritage and my grandfather’s experience, I struggled with how I could capture something that happened in the past and the invisible rays of radiation. The answer I came up with is to abandon the camera altogether and focus on the use of specifically sunlight as my grandfather described that day in Hiroshima as “hundreds of suns lighting up the sky.”

This focus on light also has led me to find ways of breaking the frame and idea of photography as a quick snapshot and instead to present these photographic images that extend over time, offer alternative visions of the future and re-present the past. Photography is not just the capturing of a moment but of several timeless moments that other mediums fail to engage with.

Hymn for a Lost Tomorrow: video still, 2022

KW + JE: Although “Hymn for a Lost Tomorrow” is deeply photographic, do you see this piece as video art? Can you tell us more about the role of photography, video, and their intersection in your practice?

KI: So many of my photographic artworks are a record of my performances. The use of objects with histories and stories and even the use of sunlight for the duration of my breath as an exposure time - these almost ritualistic processes are almost always present in my prints. As for video, this performative element is more evident as I actively perform in front of a camera.

Thus, the result of a video piece comes naturally as a next step of my inclusion of my performance aspect of my practice even though it largely stays hidden in most of my work.

Sungazing Scroll: Installation view at Maryland Institute College of Art, MD, 2018, Unique C-print photogram (Sunlight, Artist's breath), 12" x 250'

KW + JE: Your grandfather passed away when you were a child but his life is very important in your work. How did you get to know him through research as an adult?

KI: My grandfather passed away from cancer when I was nine years old and even though I do remember him telling me many stories, much of my knowledge of him comes from the books he wrote as an activist and educator and by conducting in person interviews with his friends, other relatives, and people who knew him during his many years as an activist.

The funny thing is, as I do more research, and not just of my grandfather but of other nuclear victims including Americans and other Pacific Islanders, much of these individual traumas start to overlap with each other becoming a collective trauma and perhaps a universal trauma which sometimes goes beyond nuclear issues.

KW + JE: Your work addresses collective and generational traumas that stem from nuclear war and WWII. Are there any artists you regularly look to for inspiration around similar themes?

KI: Christain Boltanski was one of the largest influences for me in terms of creating monuments/memorials like installation artworks utilizing photographic images and artifacts. The way he confronted death in order to recognize the life we have today is truly an eye opening message.

Another large inspiration is not a single artist per say but the larger post-war Japanese art movement called Gutai. Focused on avant-garde techniques and ideas that set the groundwork for and inspired both performance and conceptual art of the 60s and 70s, the Gutai movement’s ideas speak closest to my own ideology of artmaking.

KW + JE: How does addressing historical events inform viewers of your work about concerns in the present day?

KI: The past is not something that exists outside of my own reach. For me, I am constantly reminded of it through the media, my family, and several other daily occurrences. I consider every artwork I create as a self-portrait. As, just like anyone living today, my own existence is a result of every decision that came before, both good and bad. I see the threads and lines of the consequences we see today that were decisions made 30-80 years ago. It is always with us and ever present. This focus on the past is refashioned into a road map that we can utilize to hopefully navigate into a better future.

Aborning New Light: Public projection at the Daniels and Fisher Tower in Denver, 2021, Video projection, Loop 1 min 49 sec

KW+JE: What are you working on right now? What’s next for you as an artist?

KI: I am working on several new projects that touch upon the ideas of war and peace and how invisible/forgotten sacrifices are made in order for us to exist. This new direction focuses on the decisions mentioned above. Still originating from the nuclear issue and my own irradiated past, the new works examine the larger dichotomy between these supposedly differing states of the world. As for exhibitions, I am currently working on an upcoming solo show organized by the Center for Finer Art Photography and hosted by the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art in Colorado coming in the Spring of 2023.

KW+JE: Thank you again for taking this time to speak with us. It has been a pleasure learning more about your work, and we’re so honored to include your piece in the High Wall 2022 exhibition!

Burning Away #2: Studio view with the artist, 2021, Silver gelatin chemigram (Sunlight, Honey, Various Oil), 100”x41”x1” (Eight 20x24 prints)

All images © Kei Ito