Q&A: TERE GARCIA

By Jesse Egner | October 27, 2022

Tere Garcia is a multidisciplinary artist originally from Monterrey, NL, Mexico, and currently based in New York City. She graduated from the University of Houston with a bachelor degree in Fine Art Photography and Digital Media with a minor in Art History. And with an MFA in Photography and Related Media from Parsons School of Design in New York City. Her art practice has been an important tool to express, heal, and form narratives about her identity and the places where she exists. Garcia has been traveling and working along the United States and Mexico Border, confronting these boundaries that demolish and hinder unity. She intends to create and change the way these landscapes have been advertised, utilized, and exploited to generate hate, displacement, and separation for humanity.

Garcia has exhibited at Lawndale Art Center, Amarillo Museum of Art, The Houston Center for Photography, Blaffer Art Museum, Presa House, Station Museum of Contemporary Art, Northern Illinois University Art Museum.

Jesse Egner: Hello Tere! I’m very excited to speak with you today and hear more about you and your work. To begin, I’d like to hear a bit more about your background. How did you first get involved with art-making?

Tere Garcia: My interest in the exploration of materiality begins in my youth. I grew up in Monterrey, NL, in northeast Mexico, a city with a prominent position in industrial construction sectors such as cement, steel, and glass. Surrounded by construction in a city that is continuously changing and developing, I witnessed the degradation of concrete in the built environment around me—the repetition of these materials resonated throughout my childhood. I was educated to be familiar with them. School field trips to cement, steel, and glass manufacturers exposed me to industrial materials in their raw forms. Therefore my sensibility for materials and my displacement abroad has become a key element in my art practice.

My interest in photography began when I was studying architecture and ended up taking a darkroom class. Being in the darkroom and learning about the darkroom process changed my career and way of thinking. After learning the technical aspects of darkroom printing, I was able to spend more time experimenting. I was spending hours in there. I began to experiment with materiality with light sensitive paper and chemicals, I felt a need to have my hands involved in making a photograph, manipulating the process, and experimenting.

Anti-Monument, 2020

Running time 01:32

Video credit: Steven Baboun

Editing credit: Miguel Gonzalez

Drone footage: Tere Garcia

JE: Last year, I had the pleasure of seeing elements of your latest project, Anti-Monument. You exhibited a large lumen print as well as a performative video of you making this lumen print, among many others, along the border between the United States and Mexico. Can you tell me more about this project?

TG: The Anti-Monument is a body of work birthed out of my personal experience as a migrant in the United States. Since I migrated I haven’t been able to cross the US/Mexico border that separates me from my family, my culture, and my own country. My story is one of many migrants in America each with their individual stories of pain. This body of work was created along the 2000 miles of the United States and Mexico border during the 2020 presidential election. The border is a 2000 miles boundary that divides two nation-states; the barrier separates cultural forms, people and regions. The journey began in Boca Chica in the Gulf of Mexico and I concluded in San Ysidro, California

During this journey that I embarked along the border encountered invisible boundaries, and different types of fences such as the Modern Double Steel Mesh style, the Bollard style, Landing Mat, and the Normandy Fence. I began to study the architecture of the wall more and found out how the walls were erected. The first wall built in California was made from helicopter landing mats that were used in the Vietnam War. I came across another type of structure called a Normandy fence. The Normandy fence was used on D-Day during the German invasion of France. You see the same prototypes of these structures that were used in wars being brought back to the United States. Then, I saw the wall that was erected by Donald Trump. They’re building these walls not to scare, but to impose power. But in the end, they don’t really do anything. These walls are not preventing migration from happening. This monument suggests unsolved political, social, and historical issues, it imposes a new narrative in the current time and erases and negates the real historical and geographical context of these spaces.

Anti-Monument is a collection of images, videos, and sound pieces that I created during my trip to the U.S/Mexico border. I applied a 19th-century photographic process called Lumen print, a technique that implies cameraless photography. I used gelatin silver paper, light, and time to activate the process behind the compositions. So I began to intertwine the paper into the fence as a way for me to be in both sides. I was in Mexico. I was in the United States. The paper is actually collecting data from both sides it experienced a shifting human accommodation, two cultures, two languages, two different identities; it recorded power and domination. In the Rio Grande, I used the water as a material similar to the process of developing photography, the borderlands becomes my space that simulate a darkroom. I also created multiple sound pieces in different sections of the border wall. In these interventions I used objects that I collected from the area, I began to hit the wall making a sound and in a way making a protest against these walls that created inequality.

The Architecture of the Wall, 2020

Normandy Fence

Douglas, Arizona-Agua Prieta, Sonora Mexico

JE: Lumen prints–photograms made on traditional silver gelatin photographic paper using the sun–seem to play an important role in your work. Why lumen prints? What draws you to them?

TG: I often think about the endless possibilities that photosensitive paper can record without ever revealing a single image but merely recording the passage of time. I primarily work with cameraless photography and photosensitive paper to understand the photograph as an object to create a direct experience and less as an image of documentation.

For me, the act of not fixing the images in the body of work “Anti-Monument" serves as a gesture of expressing my concern with this monument. Light and time will erase the image in the contact print in the hope that these monuments can be destroyed. The marks of the gestures left behind when I intertwined the paper at the fence will stay permanently like the physiological scars and traumas that exist in every migrant that crosses these marks, these boundaries, these fences. These images of the border are not meant to be reminded or to be fixed, but to change and disappear.

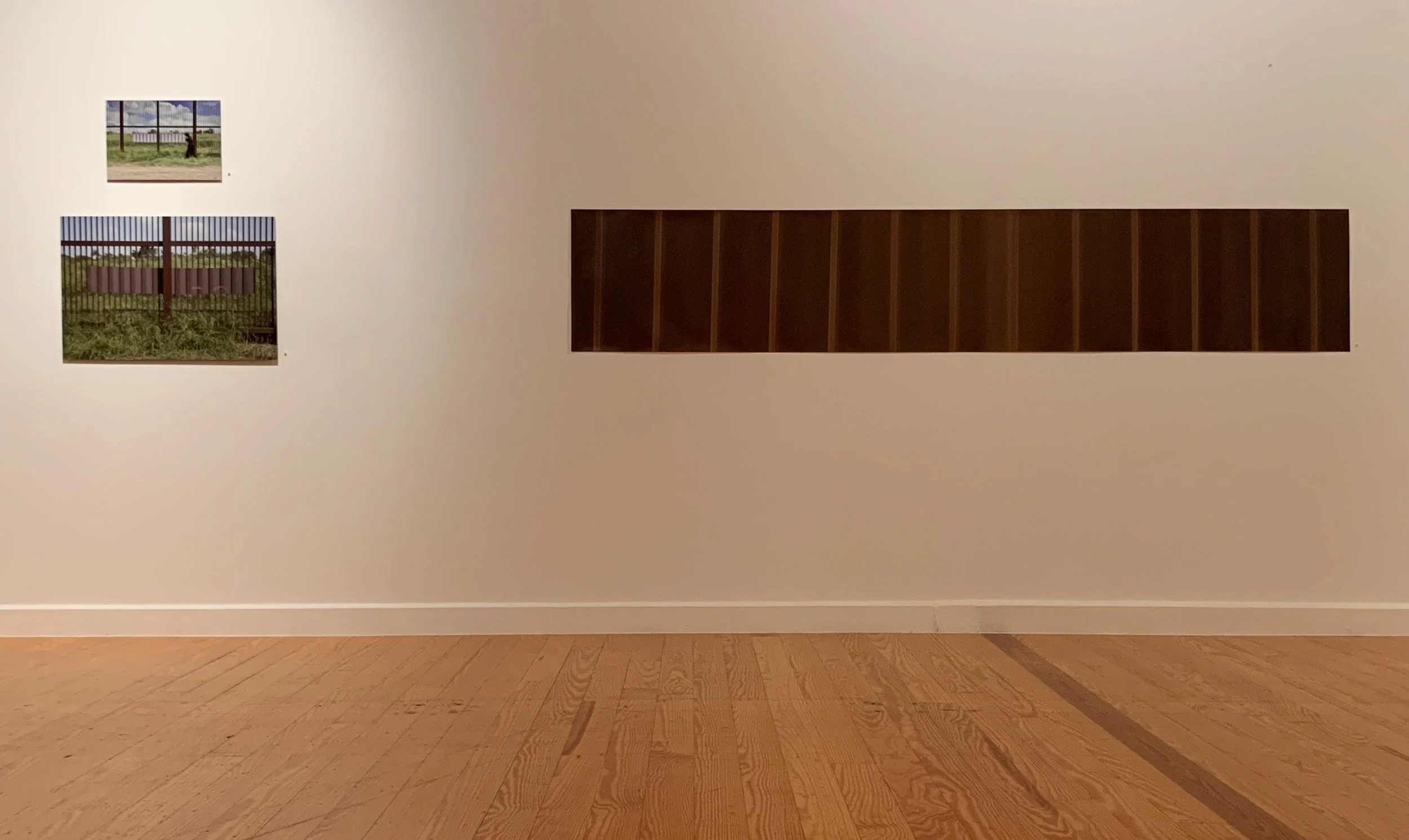

Anti-Monument, 2021

Installation View

Refuge and Refugee exhibition, Northern Illinois University

Image Courtesy of Northern Illinois University

JE: Several aspects of your work, particularly the performance and lumen prints, are quite ephemeral, as a performance truly only exists as it is being performed and a lumen print will eventually fade. What is the role of these ephemeral qualities in your work?

TG: I think it’s just the way I work. I always work in a way that is so spontaneous. Every time I went out there I didn’t know what would happen. I never plans things out. I go to the space and respond to it. If things happen, they happen, and if not, then something else will happen. There was one time where I couldn’t really weave the paper into the fence, so I thought, what can I do? Instead of weaving it, I put the light sensitive paper up against the fence and started rubbing it with my hands.

It’s the same with the sound pieces. I would just find something that would make a sound against the structure, like a rock, a stick, or a metal rod and start hitting the wall, like I was calling out making these loud sounds of protest.

I used to fix my lumen prints with a scanner, but later, I ended up just using the prints without fixing them. I use them to create an imprint and let the paper naturally develop, and later see the shifting colors until the paper turns into a dark color. This is similar to concrete–it’s a material that never really fixates. It’s always changing. Like the concrete that never completely cures. It’s always changing in a way. I let the light-sensitive paper always be in a state of flux by allowing its natural way of developing.

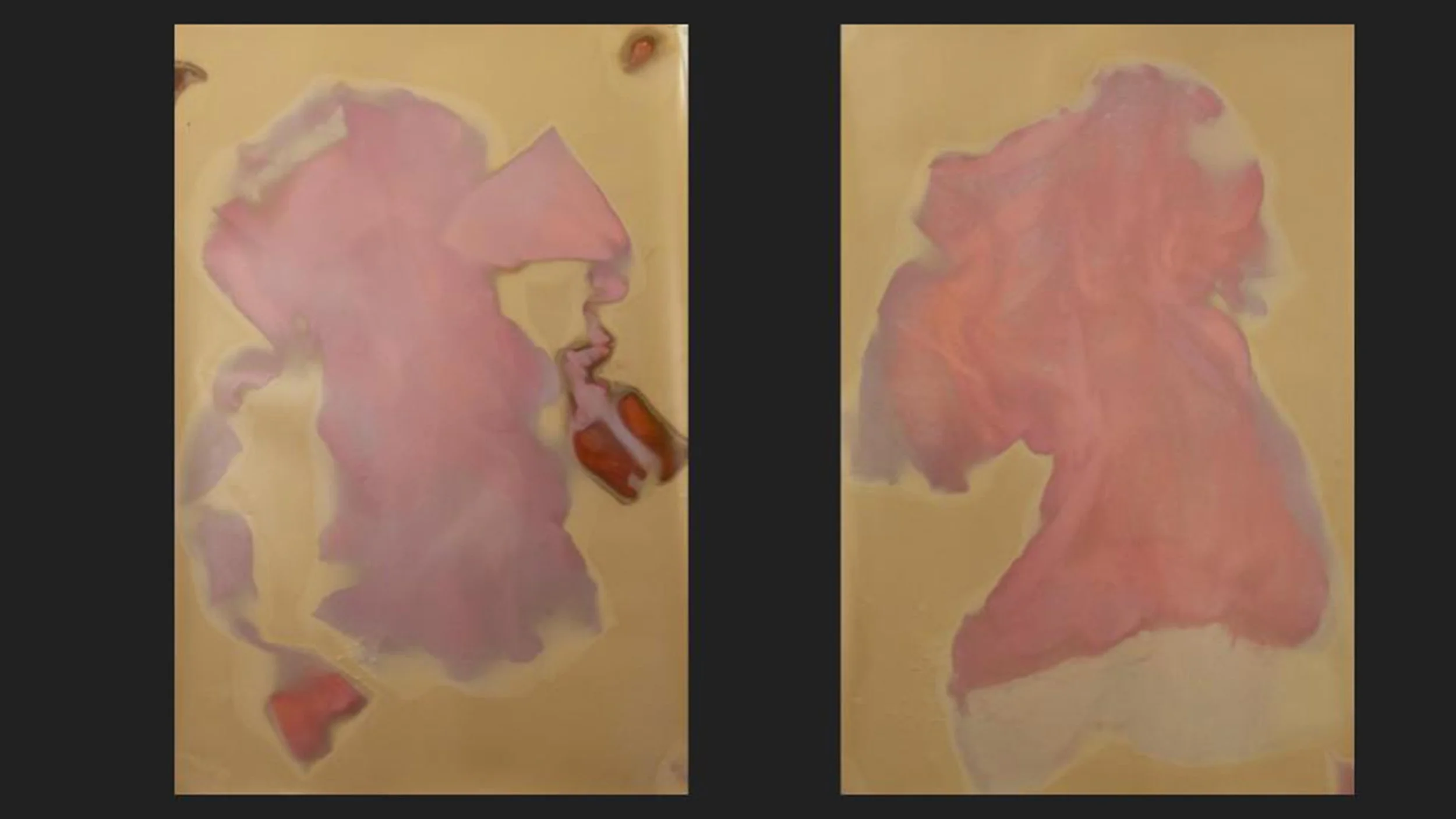

Anti-Monument, 2020

Douglas, Arizona-Agua Prieta, Sonora Mexico

November 2020

Image Credit: Steven Baboun

JE: Do you consider your work to be activism? Or, what relationship does your work have with activism?

TG: I see myself as more of an artist than an activist. I think my role is being an artist and delivering a message through my medium and the language of art. But, I do a lot of humanitarian volunteer work as well.

During 2021 I traveled several times to the desert in Brooks County, and joined the Water Drops humanitarian missions of the South Texas Humans Rights Center (STHRC). They are an NGO in charge of preserving migrant rights in border farms and ranches as they risk their lives crossing the treacherous trail. As of right now, it is critical to build and create conversations about what identity and place mean to us as migrants in the United States. In the last ten years, migrant numbers at the border have abruptly increased. The political and economic crisis in countries like Venezuela, El Salvador, Haiti, Mexico, etc. have worsened resulting in more and more migrants deciding to journey north. Clearly, the USA government is failing to appropriately protect the basic human rights of migrants crossing the border through Brooks County.

Approximately 60 miles from the United States-Mexico border, the United States Customs and Border Protection checkpoint has been strategically positioned in Falfurrias, Texas, located in Brooks County. Which forces our people through extremely dangerous and snake infested rural areas and all with the intention of diverting the route of migration, to a route of death. So far in 2021, at least more than 40 missing people have been registered.

Migrating is a human right, it should not be a necessity.

At the beginning of 2021 Matt Flores, Angel Lartigue and I began investigating these lands by volunteering at the South Texas Humanitarian Center. Our role as artists now becomes a humanitarian service where our responsibilities are to save lives and prevent the death of hundreds of migrants who are forced to take the route of death. We are artists, we work with tools to create, we build objects, we implement strategies, we do research, we invent a visual vocabulary, we create narratives and we build a new language to express our ideologies. But this work goes beyond that when I put on my long-sleeved outfit, jeans, boots and hat and we go down the road of death. Eddie Canales, the organizer of this project, guides us through this route, in which we fill and install drums full of gallons of water, to prevent dehydration of our people. But later, my work does evolve from these experiences. I’m always thinking about my work and it’s relationship to my life and responding to those experiences.

The Migrant Trail, 2021

Site-Specific installation in Brooks County

Image credit: Angel Lartigue

The Migrant Trail, 2021

Detail of lumen prints

JE: Congratulations on your recent residencies! You just participated in two residencies, one for the International Studio and Curatorial Program in Brooklyn, NY and one for the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos, NM. What have you been working on at these residencies?

TG: At ISCP I developed the body of work “The architecture of the wall” which consists of a typology of war-like fences sadistically adorned with razor wire and controlled by the latest surveillance technology of cameras and human enforcers. I used some of my documentation from my work along the border. I took close ups from the different types of architecture along the border wall and made them into a grid. Then I placed razor wire in front of the images.

When I was at the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, I started working with emergency blankets that are a thin aluminum foil. They were made by NASA and now they are used a lot in detention centers instead of regular blankets. I began to use these blankets in the studio and projecting phrases onto them inspired by the book Violent Borders Refugees and Their Right to Move by Reece Jones.

JE: What are you working on now? What’s next for you?

TG: I’m thinking more broadly about borders now, not just the US/Mexico border. I started working on another project where I’m collecting found footage and images from migrants crossing the Mediterranean, Florida Straits and Rio Grande by balsas/rafts. I put these images into a grid and make cyanotypes from them. I’ve also been experimenting with textiles, using clothing left behind at the border that I collected while I was doing water drops in South Texas. I also will continue the humanitarian services in the desert of Brooks County.

JE: Thank you again, Tere, for taking the time to speak with me! It’s been a pleasure hearing more about you and your work.

The Architecture of the Wall, Installation View, 2022

The Architecture of the Wall, Detail, 2022

Anti-Monument, 2020

Fort Hancock, Texas-El Provenir, Chihuahua Mexico

November 2020

Image Credit: Steven Baboun

Anti-Monument, 2020

Installation View

In The Sun exhibition, The Station Museum 2021

Emergency Blankets: Violent Borders, 2022

Running time 00:31

Emergency Blankets: Violent Borders, 2022

Installation View

Emergency Blankets: Where Is My Right to Have Rights? 2022

Installation View

Balseros, 2022

Mediterranean, Rio Grande, Florida Straits

All images © Tere Garcia