Q&A: Tarrah Krajnak

By Rafael Soldi | January 10, 2019

Tarrah Krajnak was born in Lima, Peru in 1979. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Art at Pitzer College in Claremont, CA. She has exhibited nationally and internationally at the SUR Biennial in Los Angeles, Honor Fraser Gallery, Silver Eye Center for Photography, Center for Photography Woodstock, San Francisco Camerawork, Philadelphia Photographic Arts Center, Filter Photo Festival, Art London, Art Basel Miami, The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Columbus Museum of Art, The Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, and Ampersand Gallery & Fine Books. Her work has appeared in both print and online magazines including the LA Review of Books, Nueva Luz, and Camerawork. She received grants from the Harpo Foundation, The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Vermont Council for the Arts, Vermont Community Foundation, and the Arizona Commission on the Arts. Recently her book dummy El Jardin De Senderos Que Se Bifurcan was runner-up in the 2018 Unseen Amsterdam Photobook contest. Krajnak's solo exhibition "Origin Stories" is currently open at the Houston Center for Photography through January 2019.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Tarrah, thanks for taking the time to chat with me.

Tarrah Krajnak: Thank you for reaching out Rafael! I’m so glad we are finally connecting.

RS: I’ve been really looking forward to our conversation. We were both born in Peru and now have an art practice here in the US, but our paths here were very different. Fill me in on your backstory.

TK: My “backstory” is sometimes difficult to tell because my family history and my relationship to Peru is made up of so many conflicting narratives. Here is one version of my backstory:

I was born in the “pueblos jovenes”- in the dusty outskirts of Lima, Peru in September, 1979. My birth mother left me in the care of an orphanage run by an order of German nuns called the Sisters of the Sacred Heart. These nuns facilitated hundreds of adoptions of Peruvian children to Europe and the United States between 1975-1990. I was adopted as an infant by a working-class Czech-American couple from the anthracite coal towns of eastern Pennsylvania. My parents adopted 3 children that winter of 1979 over a span of just 3 months including my African American “twin” brother Todd from Philadelphia, and my sister Maria from an orphanage in central Peru. We moved through a constellation of blue-collar suburbs from New Jersey to Illinois, eventually settling down outside of Cleveland, Ohio in a nearly all white suburb.

I grew up surrounded by TV, team sports, and tanning beds, with little access to art. When I turned 14 I left catholic school to attend a public High School where I immediately quit sports to write bad poetry and hang out at record stores and music venues in Cleveland. I guess you could say my first access to art was through the 1990’s Cleveland music scene. From there, I attended a small liberal arts college not far from home– Ohio Wesleyan University. When I arrived as a freshman I was pre-med just like all the other first-gen students, but I quickly discovered darkroom photography, contemporary art, and the college radio station. At that time, I still didn’t really understand that one could be an artist. I spent a short stint in NYC as a photo assistant at Saturday Night Live. I then went to graduate school at the University of Notre Dame. I studied with Martina Lopez and she really validated my conceptual interests in family archives. I’d never worked with a woman photographer before, let alone a person of color until then.

RS: At some point in a recent chat you presented to me a perspective on adoption that I had not considered before—you talked about adoption as a way to imprint an identity on top of another. Essentially, assimilation.

TK: International transracial adoption requires the movement of brown bodies across and between families, races, nations, language, culture, class. On one hand, yes, a new family and a new identity is gained, but on the other something is always lost. In the 1970’s adoptive parents like mine embraced a strategy of “color blindness”. My siblings and I were all raised with the understanding that our outsides simply “did not matter” and that “we were all the same”. Think about what this might look like though? In my case, my “twin” brother is a six foot tall 300 pound black man and my sister is a four foot ten petite Andean woman and my mother is a large blonde hair blue-eyed Slovakian woman. However, brown and indigenous bodies are always marked visually. As a transracial adoptee I have spent my entire life navigating an imprinted identity that will never match up with my actual body.

Hysterical Eye, from Tarrah & Wilka: Hysteria Collection

RS: We’ll chat shortly about your relationship to Peru in your work, but the early years of your career were marked by a significant and lengthy collaboration. How did this come about?

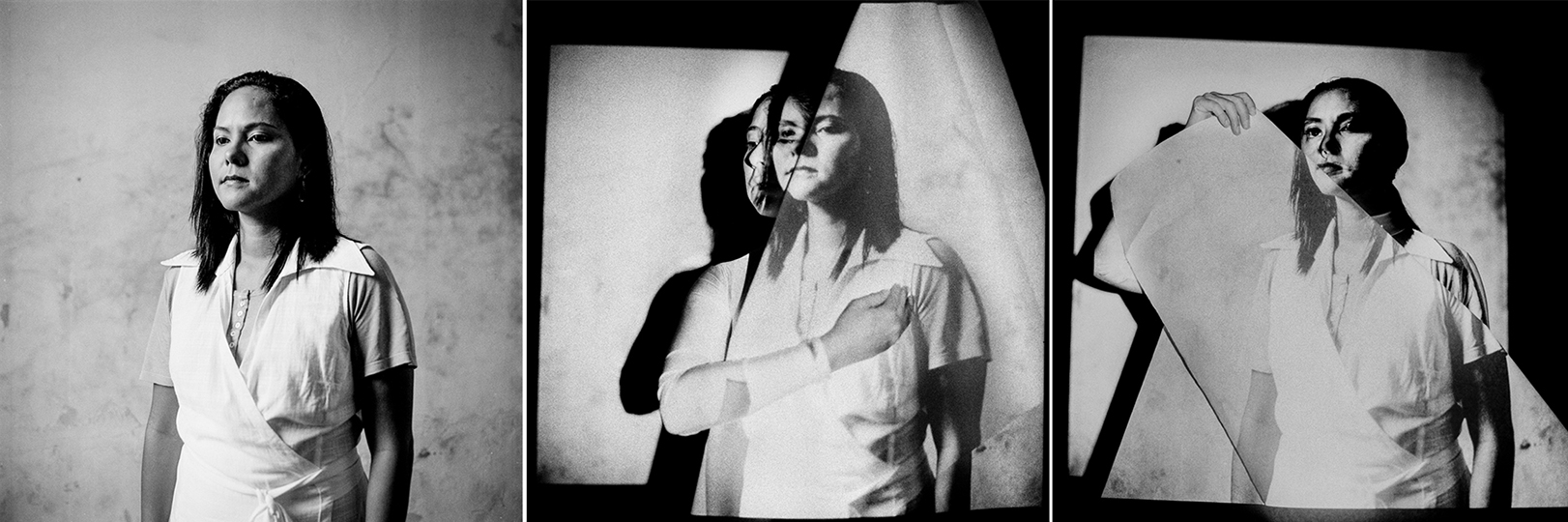

TK: I was only 23 when I graduated with my MFA, but I made a serious body of work over those 3 years that focused on the family album and racial taxonomy. That experience laid the groundwork for the work I made directly after graduate school with a Puerto Rican photographer named Wilka Roig. Wilka was in her final year in the MFA program at Cornell when I arrived for my first “real” job in 2005. At that time we were both photographing our bodies and using performance, but what really prompted us to start working together more formally was this sexist critique by Matthew Higgs. He was a visiting critic that year at Cornell and came to our separate studio spaces for a visit. When we got together afterwards to share our experience we found that he had simply given us the same critique line verbatim, “As many young women who turn the camera on themselves your work is over burdened by emotion”. I’ve told this story many times because I think it was a really important moment for me as a young woman of color photographing my own body. I took this critique very seriously and the dialogue between Wilka and I that grew out of that very dismissive and negative critique became the basis for the beginning of our collaboration. We thought that this critique related to something larger going on with the state of women in photography at the time and we started to look more closely at how women and our bodies had been represented throughout photographic history. We paid particular attention to how contemporary trends might be traced back to 19th century photographs of hysterical women “over burdened with emotion”.

RS: That kind of rhetoric is so old and tired—I love that you both flipped the power structure. So, when did this collaboration come to an end?

TK: The collaboration ended when our geographical locations shifted for job related reasons and this in turn generated different questions in our work as artists. Wilka returned to Puerto Rico and shot some really beautiful personal work and then eventually moved to Mexico to pursue work as a therapist. She recently described her move to Mexico as “returning to my language, my culture, my environment, my air" and the place where she "no longer had any questions about belonging". I was working in my Vermont studio re-photographing the 20th century portraits of indigenous Peruvian photographer Martin Chambi. In hindsight, the Chambi re-photographic project was a way for me to return to Chambi’s romantic vision of noble Andean peasants in a misty Cusco, but I understood then that “my Peru” would be very different. When I finally did return to Peru in 2011, I was nearly 30 and the culture was not mine, the environment was not mine, the language was not mine, and the polluted Lima air made me sick. However, it was also the first place I was surrounded by faces and bodies that resembled mine so the experience was unsettling and one of displacement or dislocation. What I learned about belonging was very different from Wilka’s Mexico experience. I will always carry with me the circumstances of my own identity and the burden of my personal history no matter where I go. Home and belonging for me is rooted in movement and the absence of place.

RS: What effect did this have on your practice moving forward?

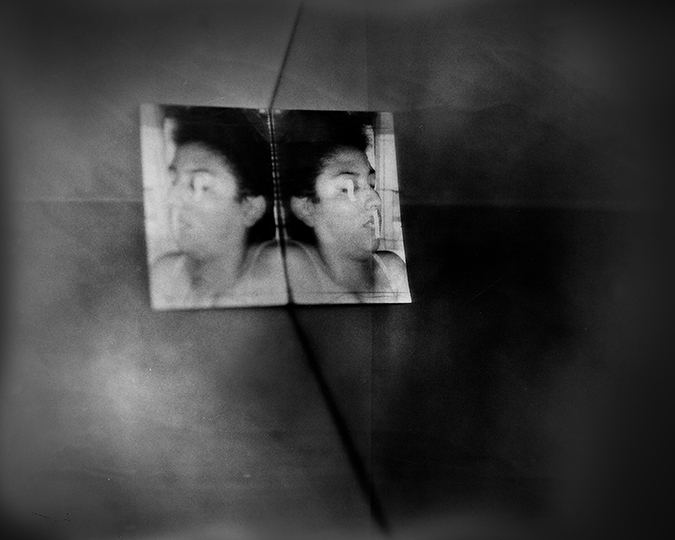

TK: I put all my artistic energy and all my best ideas into that collaboration for several years which is a long time to work with another artist—especially for me since I was in my mid-twenties when we started. The collaborative work launched both our professional careers as we won some important fellowships and did solo exhibitions and speaking engagements across the country. I truly had to re-invent myself and my entire practice after the collaboration ended. I had to learn how to make art again in the absence of a woman I had so closely tethered my own identity to quite literally. In the work you can see this power dynamic play out where there is always a doubling or twinning, a mirroring effect which is still very present in my current work.

Twin Beds, Coaldale, PA, 1989, 2001

RS: Yes, even going back to your childhood, there is a recurring theme of twinning and doubling in your work—like the Time Twins series. This is also mirrored on formal elements in your work—you rely on reproduction and juxtaposition to break down images and create/strip meaning.

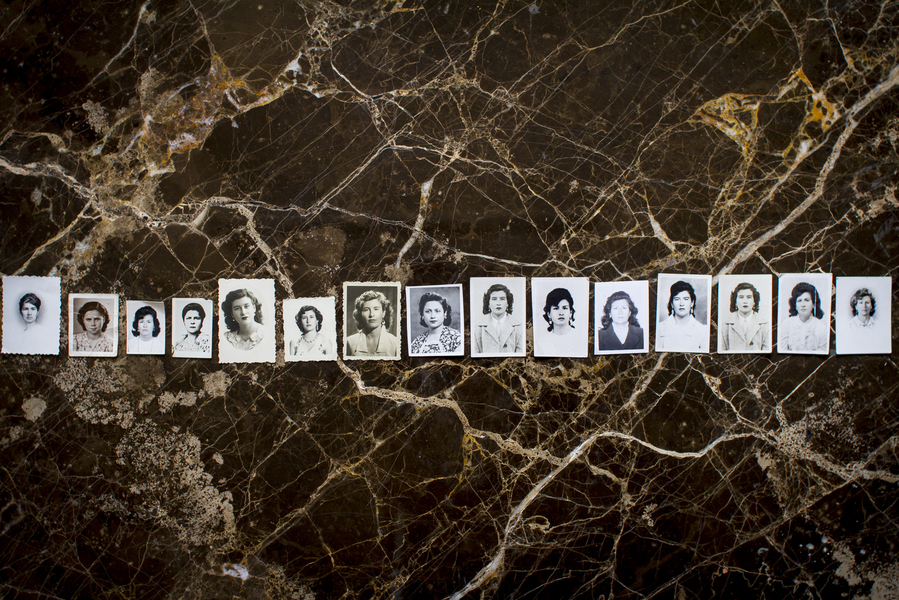

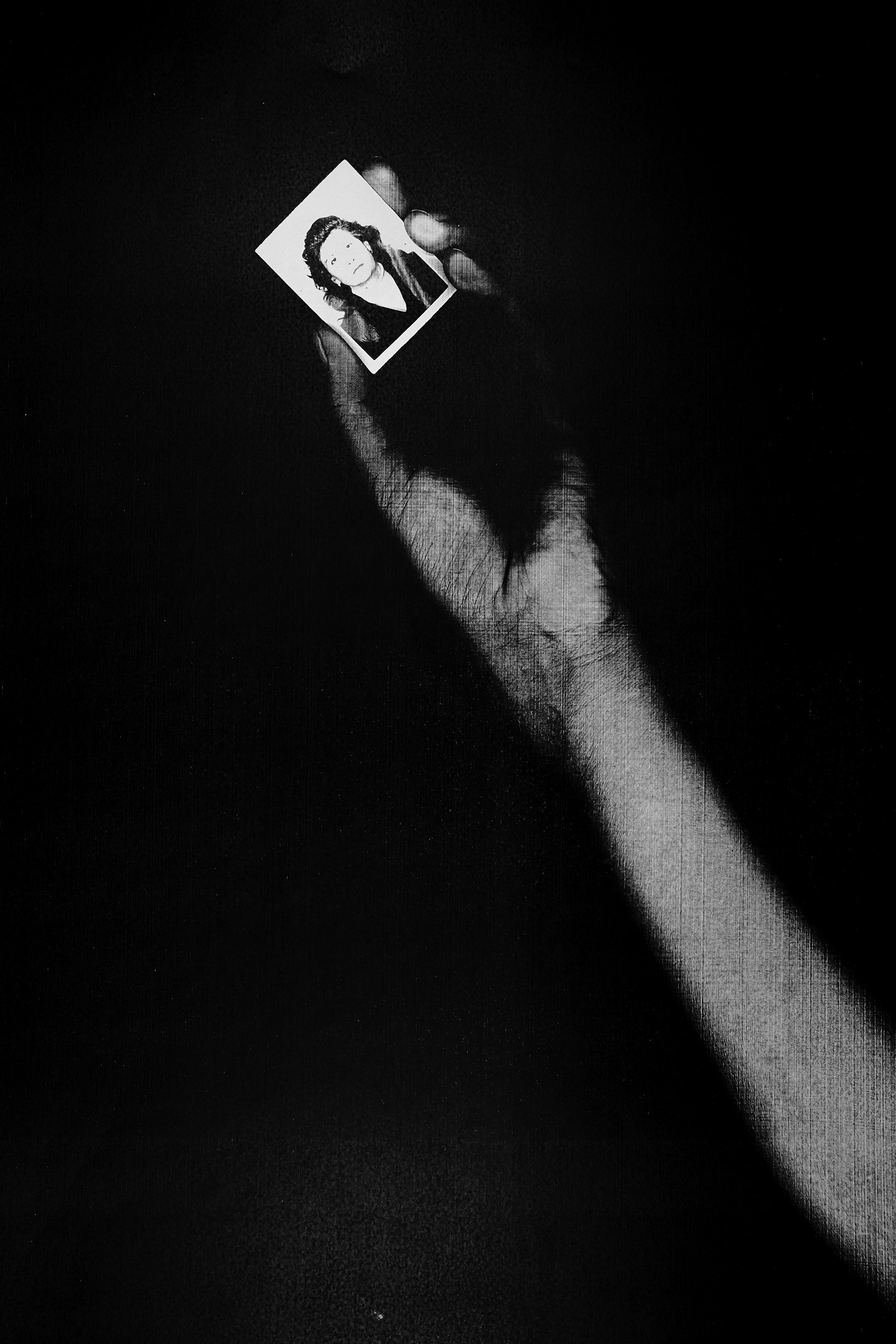

TK: Yes, in my work I consciously use doubling both as a formal and conceptual device as a way to point towards the search for origins. For example, in both SISMOS79 and Senderos I use an archive of found photographs I collected in Lima of passport photographs of anonymous women. All of those photographs were collected over a long period of time in separate locations on different days. They depict different women of all different ages. By chance, when I laid them out in my studio I found I had two identical photographs. I then consciously started looking for copies, pairs, or sets of portraits that seemed like they might be the same person. It is all done through careful editing and sequencing though—in both projects juxtapositions are made to force the double. In my book project Senderos you can see twin beds or the photo of a double-headed goat and I took those photographs years apart and yet through editing they seemed to emerge as a pair. I also use formal devices like xeroxing and re-photographing or copying as an act of doubling to reflect on the act of photographing itself.

RS: I’m really interested in this recurring elements in your work—sometimes we unknowingly make work that will support important other work years in the future. So, you went to Peru with support from a grant; how did you spend that money?

TK: I moved to Peru and rented a studio in Barranco. I hired a young local art student named Carola Casusol. I lived in Barranco for 3 months and spent the time collecting vernacular photographs of anonymous women. I also collected over 200 political and pornographic magazines from my birth year 1979. I still have very limited ability to speak Spanish so my engagement with Lima’s political history and my access to the culture at first felt very visceral and limited to a visual experience- in many ways it still does. I spent every day walking and listening carefully to the new sounds, struggling to communicate and at times feeling real shame that I could only speak English. I realized though that I didn’t have to learn all of Peru’s history in 3 months nor did I have to speak fluent Spanish to make art work. My project SISMOS79 became about this process of unraveling my own position in relationship to this complex history slowly over time which is why it has so many layers and sub-series. I used my camera to connect with my surroundings and with people. I did a lot of street photography, architectural photography and food photography too. I went dancing a lot at this club that played 80’s and 90’s goth music and it really became a place where I fit in because there were so many other 30 something Peruvians who only spoke Spanish mouthing the words to Smiths songs they had memorized. Before I left I started a series of portraits called Time Twins—I posted ads for women born in Lima in 1979. I asked them to pose for me and I recorded their personal stories even though I could only understand a few words.

Sismos79, Barranco Open Studio, Lima, Peru. 2013

RS: How did meeting these women and working with their stories help you better understand yours?

TK: As I developed the project further I was also working on my writing. I was studying poetry and language in writing workshops and I started to think of the language barrier as a really important part of the project. I took the recordings of these women out a full 7 years later—just this past year actually. I started memorizing the stories to hear what I would sound like saying their words in Spanish and then used google translation as a way to point to the nature of collective histories and the construction of memory. This process of re-writing these stories through the use of memorization and Google translate provided a mechanism for mis-translation and mis-remembering to be built into the meaning of the work itself.

RS: So in finding all this archival material from 1979 you encounter a country in a state of unrest, and thus much of the imagery has a nefarious quality to it—political turmoil, violence, and the emergence of terrorist guerrillas. I’m interested in the type of imagery and themes that this introduced into your work, both the expected and unexpected.

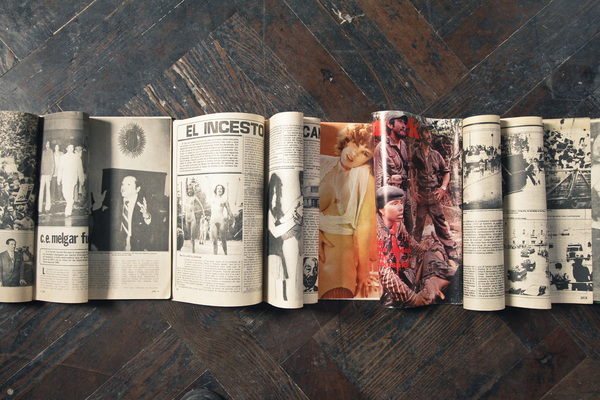

TK: The print culture of Lima around 1979 is really fascinating to me. I am still studying all the political and pornographic magazines I collected. There is so much material here. I was interested in the depictions of violence against women, rape, and child prostitution, but I was also surprised to see so many queer bodies, trans bodies, and many stories featuring hermaphrodites and /or castration. There was a lot of reference to surgical alteration of bodies juxtaposed with religious cult imagery as well as sleazy home-made porn mixed with images appropriated from foreign magazines like Playboy. I am still making new work from this imagery, specifically looking at sites of violence against women and prostitution as it relates to the migration of indigenous bodies into Lima and the emergence of the slums where I was born. 1979 was a seismic moment in Peru’s history as the city’s population was rapidly swelling and the racial make-up was changing at the same time. You can see this eruption in the magazines through these depictions of marginalized bodies and just how violent this time period must have been and how it was felt in the city itself in the streets and by the people.

RS: Your exhibition Origin Stories is currently up at Houston Center for Photography through January 13, 2019. You mentioned in one of our chats that at some point you thought you were done with this work but could not part with it. Sometimes there’s the work we make as we process the information we have, and the work we make when we distance ourselves from it. The latter seems true of Senderos Que Se Bifurcan, which is on view at the HCP exhibition. What felt unresolved in your previous explorations that this work addresses?

TK: Senderos Que Se Bifurcan started out as a book project drawing from this larger body of work I had done in Lima under the name SISMOS79, which included video and objects and photographs and archives. The SISMOS79 work is so layered that it became difficult to show as a coherent series. So I had been showing the work for 3 or 4 years and wanted to make a book that would mark an ending to the project, a way to complete SISMO79 where all the layers might be made visible through writing and reflection. As it turned out the book marked more of a beginning, as well as a return: after the work with Wilka I took my body out of my work. I had not taken a self-portrait in nearly a decade. At the time it was a way for me to re-invent my work, but with this Senderos book I really felt like touching the archive, holding the photographs and interacting with the pain they traced required my body to be visible. For me this has to do with the trauma of the archive, what it is like to engage with difficult photographs and what it might mean to be a product of rape. What it might mean to go back to the beginning of things and find this violent act there.

Origin Stories, at Houston Center for Photography

RS: Speaking of re-inserting yourself. One common thread in your work is that of writing yourself into history. Tell me about Ansel.

TK: The full title is Master Rituals: Ansel’s the Making of 40 Photographs. I love modernism and I love teaching this history to my students, but I always find myself very conflicted as a woman of color. I was really interested in looking more closely at the phenomenon of photographic mastery and how we understand the history and canon of the photographic medium as a story of fathers and masters. Adams’ photographs also remain synonymous with the mythology of the American West and helped to shape the modern fantasies of the untouched raw nature of landscape– one that is deeply rooted in colonial expansionism and indigenous genocide. In 1983, the year before he died, Adams published Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs, an influential account of the circumstances and technical considerations — the stories — behind 40 of his most celebrated images. In my project, made 35 years later, I insert my own photographic archive over Adams' while using my own body, hair, and hands to redact his words and alter, estrange and obscure his original photographs.

RS: What’s next for you?

TK: I have a solo show up right now in Houston through January 13th. I just won a Harpo Foundation Grant in December so I’m going to use the money to finish the Ansel project and make some larger darkroom prints of the Senderos work. I am also in the midst of trying to find a publisher for my Senderos book project. I spent eight years on that book and the poetry component is really important to me so I am seeking the right fit whether in the poetry world or the photo world. I was just awarded a fully funded scholarship to attend the Charcoal book reviews so I’m really excited about heading to Montana for a week of photography and books in March. I also teach full-time and just received tenure at Pitzer College. I curated a poetry reading for an exhibition and course I’m teaching called “Publishing Against the Grain” this Spring. I have been working the last few years to set up a risography press and photo-book room that will open next month. A lot going on!

RS: Indeed! So much ahead for you. Congratulations on all your success and upcoming projects. We’ll be following along. Thanks for your time.

All images © Tarrah Krajnak