Q&A: Stine Danielle

By Lodoe Laura | February 20, 2020

In the summer of 2016, Stine Danielle left Toronto to spend three months with her grandparents in their home in the Philippines. Danielle began making pictures of her Lola–her grandmother–during the long days they would spend together around her home in the Province of Batangas. The project would take on another meaning, as a year and a half later, her Lola was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

In January, Danielle returned to the Philippines to continue the ongoing series, named after her grandmother. In this interview for Strange Fire Collective, Lodoe Laura speaks to Stine Danielle about the origins of the project, and about the complicated experience of photographing a loved one.

Lodoe Laura: Stine, I recently saw some images from your ongoing project, Rosamyrna. Can you talk about the origins of this project? What initially made you want to make pictures of your Lola?

Stine Danielle: The project started in the summer of 2016, three months before the last year of my undergrad. I had flown back home to the Philippines with the intention of shooting a project for my senior thesis. Initially, I wanted to pursue a project on my great-grandfather, Jose Villa Panganiban: a Filipino author, poet, and lexicographer whose magnum opus was writing one of the Philippines’ earlier Filipino-English thesaurus-dictionaries. When I arrived, I learned quickly that much of his work had disappeared with the exception of recent editions of his book that my Lola Rosamyrna, his eldest daughter, kept in the bottom drawer of her bedside table.

In their early 80’s, both my grandparents were still working and active in their community until early 2017 when, along with many local businesses, their shop was torn down to make way for a mall. They had owned the last standing Kodak store in their province, servicing mostly students and nearby locals, digitally printing student IDs and family snapshots. In the early 2000s, in an effort to expand their business and cater to growing local interest in the internet, they renovated half of the Kodak store into an internet cafe.

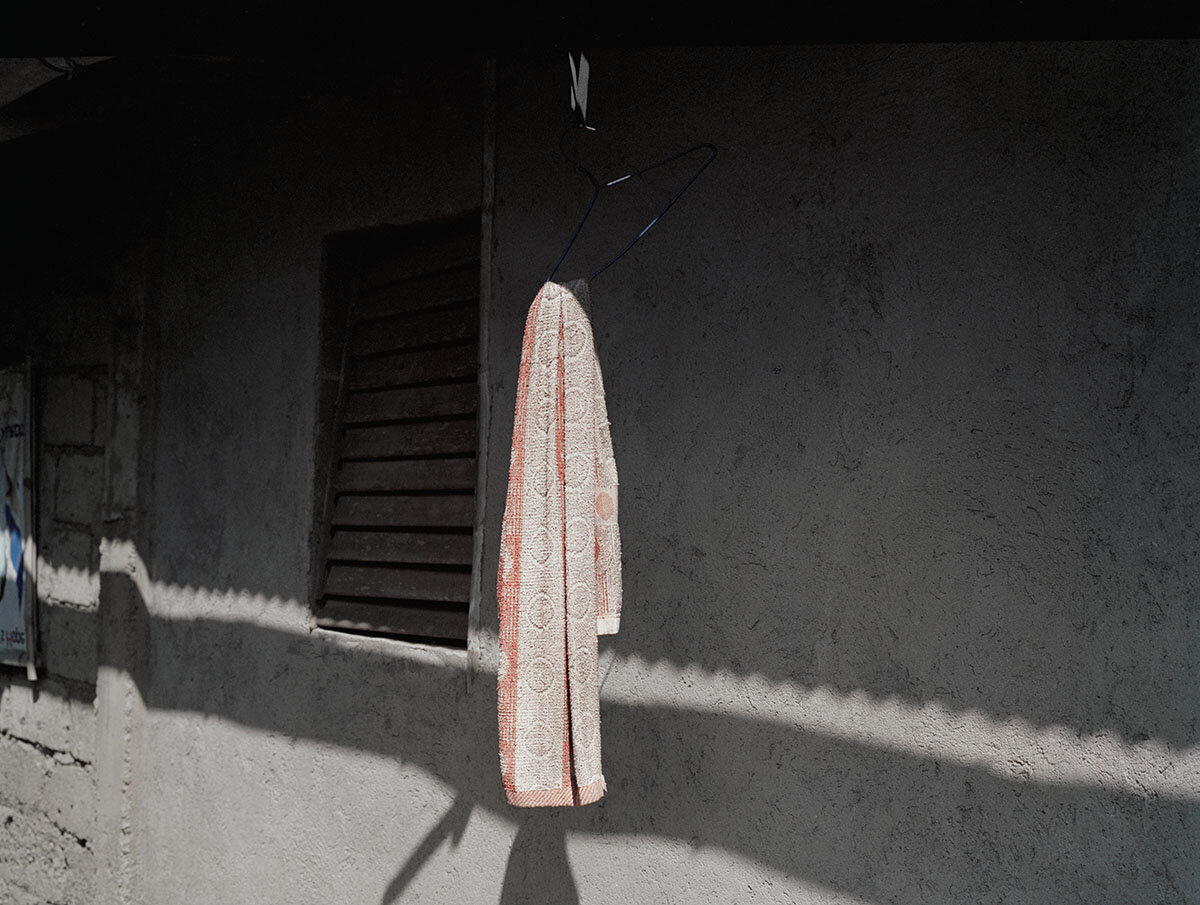

These days, my Lolo oversees property they own, including a local cemetery and farmland, and volunteers with an organization that invites international doctors to provide medical, surgical, and dental services to underserved areas in Batangas. Meanwhile, Lola spends most of her time at home reading and sewing reusable patchwork shopping bags on her 50’s Singer, giving them away to loved ones and strangers.

While living with them, as Lolo tended to his responsibilities during the day, I stayed with Lola. We’d spend the mornings lying next to each other watching reruns of her favorite telesarias, and spend the afternoons riding down J Gonzalez Street, across Mabini Avenue, with Lola repeating the same stories she passed down to my mother to me, the same stories my cousins and I can all recite now because of how often she’d repeat them to us: the bank my Lolo once worked at, down by the river my mother and her siblings used to play in, just a few blocks down the old ancestral home that’s since been abandoned but still stands today, a decaying symbol of the past next to a shiny new Caltex. With my original project idea out the window, I naturally photographed what was nearest and most dear to me, or rather who, and that was Lola. But by then I didn’t know that the photographs I would take would become the project that’s developed today. I wouldn’t have anticipated that the woman whose stories had been ingrained in me throughout mine and my family’s lives, whose memory I’d come to rely on and learn so much from had been changing quietly and then, as we spent more time together, would become apparent to me so quickly.

LL: It sounds like you went back to the Philippines to photograph intentionally, but something more organic took place. How did your Lola feel about being the subject of your pictures?

SD: At first I was a little afraid of how Lola might react. When I started taking pictures of her it was from a distance, often of her from behind while she was sewing her bags or reading the local balita in the kitchenette of her upstairs bedroom. But when we started our morning walk routine around her neighborhood compound, some miles away from the foot of Mt. Makiling, she immediately directed me. On our first walk alone, I noticed some overripe mangoes had freshly fallen from a tree. I’d already finished focusing my lens on its juice still spreading out onto a paved road when Lola sucked her teeth, so loud I mistook the noise for accidentally firing the shutter. When I looked at her, she was already pointing her lips, a not that - but this, in the direction of a malunggay tree. She walked over, stood below a low hanging branch and quickly snapped off its pods. Facing me, she held her thumb and pointer finger up in my direction, gesturing me to snap a photo of her holding the pods. I think she enjoyed being the subject of my pictures but I think she especially got a kick out of (still) being able to tell me what to do.

LL: You spoke about changes you noticed to your Lola’s memory. How did learning about these changes affect your picture-making?

SD: The first time I noticed a change to Lola’s memory was during my first week living with her. One afternoon, Lola asked me to lay next to her in bed to watch a rerun of Provinciano. As the show cut to a commercial, she turned to me and asked about my Mom and Dad. “Are they still loving?” I had to remind her that they’d divorced six years ago. She paused. “So, they let the love run out?”

I felt a responsibility to be careful with how to approach the questions she’d later ask. I treated my answers with patience and reassurance. Not with criticism or correction. My picture-making, which at first felt spontaneous and intrusive, followed in this approach. Through my making pictures of her, she was able to communicate what she wanted.

Part of communicating with someone with middle-stage Alzheimer’s is offering visceral cues. You encourage participation in their every day. And when there is nothing left to say, you learn that each other’s presence is enough. Amongst relatives, a joke developed that Lola and I were friends because she would refer to me as mars, a term of endearment amongst close friends, but truly a friendship did develop between us. I like to think I started as a granddaughter taking pictures of her grandmother, but then I became a friend taking pictures of a friend.

LL: I watched my Papa go through all stages of Alzheimer’s disease. I remember it being really difficult to watch parts of my granddad’s memories fog, and then disappear. But I also remember that, even in the advanced stages of the disease, he would crack jokes or tell a clever story that would remind me of how he would act before the dementia had noticeably affected his brain. I see a melancholy in the pictures of your Lola, but there are also moments of familiar cheekiness—like the image of her with her lifting her shorts outside her home in Santo Tomas.

SD: Absolutely. As outsiders we’re always hoping and waiting for those moments where our loved ones’ might temporarily return to their former selves. That’s why those photos of her are my favorite. One day, as we stood outside her home, Lola turned to me and said, “I want to do something scandalous before the tricycles drive by and see me.” She laughed as she lifted the hem of her shorts above her knee. I took her picture.

It was a glimpse into her old self before the disease, but for me, it was also something new. I hadn’t seen that side of her before, so bold and brazen. I sometimes feel I’m learning more about my Lola now than I did as a child growing up.

LL: There are photographs in the series that are a lot older than the ones you took in 2016—ones where Lola looks a lot younger. Can you talk about those images and your choice to include them in your work?

SD: I found the older images in late 2017 in a weathered photo album by Lola’s bedside, beneath a pile of newspaper clippings and sewing patterns. They were photographs Lolo had taken of her during a trip to Sydney in the late 70’s. Unfortunately due to age, moisture and extreme temperatures, mold developed and the colors have since changed. It wasn’t until this past January when Lola was officially diagnosed that I decided to include them in the work.

After the diagnosis we were all asking ourselves different questions: Why her? How did this happen? How can we help her? How can we manage it? In the past, she’s shared a number of stories including growing up during WWII, her family hiding in the mountains during the Japanese occupation. Like many, she’s experienced a number of traumatic experiences. I was and still am worried about what she might recall. I’m still trying to understand why I’ve included the older images, but perhaps it comes from my hope that if she does recall anything, that they’re her most cherished memories: the celebrations, the vacations, the reunions; time spent with her loved ones.

LL: It strikes me that, in the photographs I’ve seen of the project, Lola is always pictured alone.

SD: As the project continues I’m hoping to incorporate images of her with others. I’d very much love to photograph Lola with Lolo, along with other relatives. Self-portraiture is something I often do in my work so with Lola’s permission, I’d also love to take a few photographs of us together.

LL: What is your relationship to nostalgia?

SD: I have a weird, quasi-romantic relationship to nostalgia. I’m terribly sentimental about my past and its relationship to those around me. It shows in the stories I often share, especially of my mother whose journey of becoming a peach farmer in Fresno and moving to San Francisco, inspired me to go on a similar journey there. It shows in the way I traverse Mississauga, the city I grew up in, and how I often visit the thirteen different places I’ve lived in throughout my twenty-three years of being there. It also shows in the way I often write about the people I love and have loved and how - in stupid detail - I can recall their appearance, their words, culminating in the many ways they’ve impacted me.

It goes without saying then that it shows through my making pictures about all those very same things. Jokingly, I’m in a committed relationship to it. I doubt that I’ll ever stop making pictures in this way. I doubt that I’ll ever stop living in this way either.

All images © Stine Danielle