Q&A: Shikeith

By Rafael Soldi | Published November 12, 2020

Shikeith is originally from Philadelphia, PA, and now lives and works in Pittsburgh, PA. He received a BA from The Pennsylvania State University (2010) and an MFA in Sculpture from The Yale School of Art (2018). Within overlapping practices of visual art and film making, he investigates the experiences of black men within and around concepts of psychic space. He has shared his work nationally and internationally through recent exhibitions and screenings that include The Language Must Not Sweat, Locust Projects, Miami, FL; Notes Towards Becoming A Spill, Atlanta Contemporary, Atlanta, GA; Shikeith: This was his body/His body finally his, MAK Gallery, London, UK; Go Tell It: Civil Rights Photography, Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA; A Drop of Sun Under The Earth, MOCA LA, Los Angeles, CA; Labor Relations, Wroclaw Contemporary Museum, Poland; and Black Intimacy: An Evening With Shikeith, MoMA, New York, NY. He is a 2019 recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grants.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Shikeith, thanks so much for taking the time to chat with us.

Shikeith: Thanks for having me!

RS: Your work largely investigates the experiences of Black men through an exploration of interior space. What aspects of how Black men are commonly represented are you interested in challenging, and how are you doing that?

S: First, I want to point out that I'm not interested in being a moral compass as it pertains to Black men's representation. There's an unruly expectation for Black artists to counter all derelict cultural images of Blackness produced within the public imagination. I am addressing when our actualities as Black men become intertwined with phobic ideas of ourselves-when it becomes necessary to do the work of disentangling. The aforementioned does not suspend at the artwork; I lead a life that encourages acts of care amongst Black queer men and yields space to a limitless self-vision.

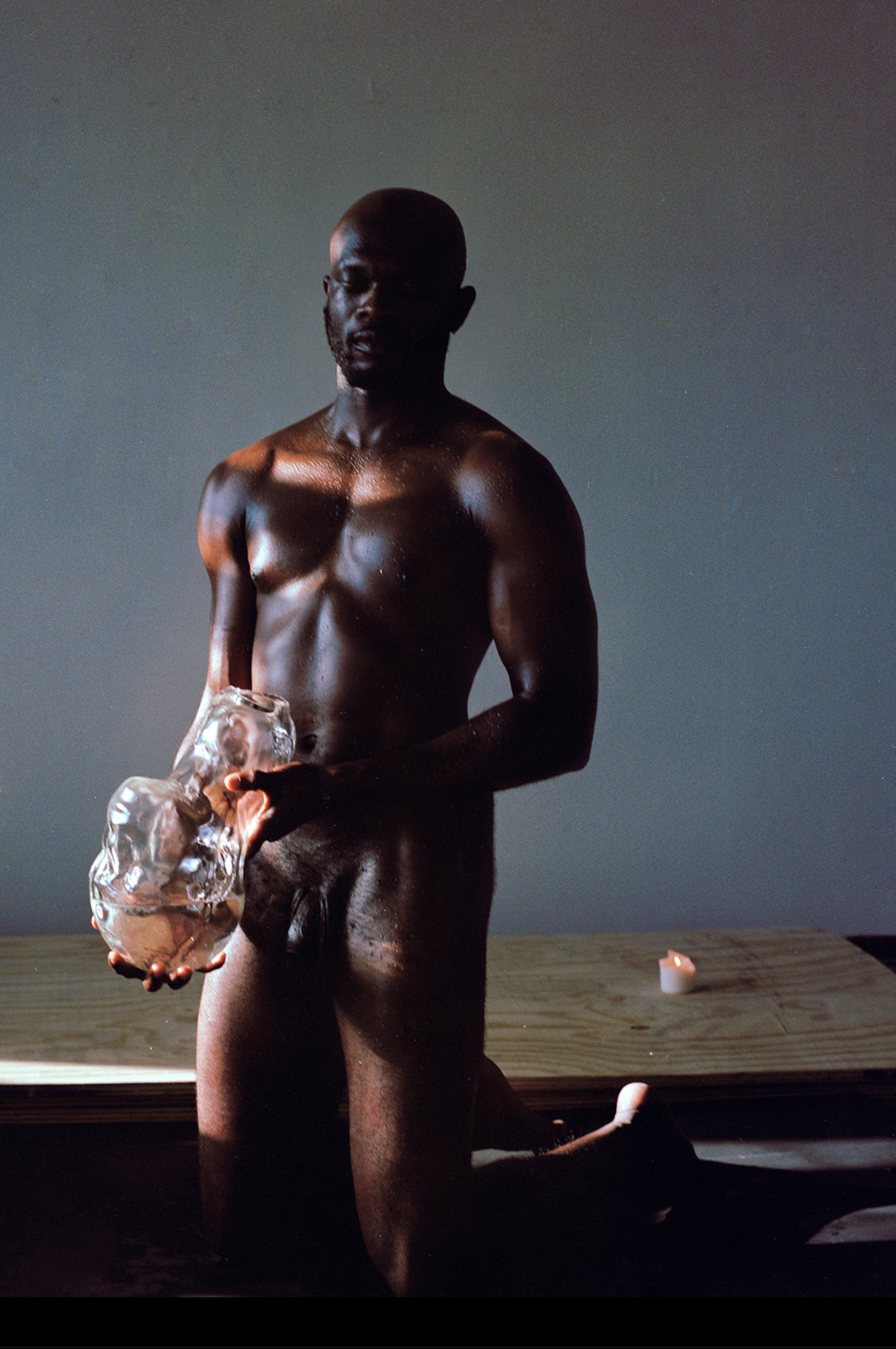

‘the language must not sweat’ (2018)

RS: You achieve this through a variety of mediums—installation, filmmaking, photography, sculpture. How do you decide when to use what medium? Do you feel that all these mediums combined form your voice as an artist, or do you feel a special kinship with one in particular?

S: Working across these different mediums demands a distinctive kind of listening to ones' gut. It's not easy, but I have gotten stronger at deciding which way to go through an alchemy of experimentation. That process of allowing ideas to revise and exist in many mediums forms my voice as an artist. Though I have no preference, I started intently making photographs when I was 15 years old, so I have a special relationship with that medium because it has been with me the longest.

RS: You’ve employed Haint Blue in many of your works. What is Haint Blue, and how does it inform your work?

S: It's a shade of blue born out of enslaved Africans' spiritual practices living in the low country of South Carolina and Georgia. It was a means of protection from haints, which is southern vernacular for ghosts. They painted the entryways and porch ceilings of their houses with this color to create a barrier between their home's interiors and wickedness. A significant aspect of my practice is mapping through a language of materiality, the untangling of colonized psyches, or Black men's interior worlds. Haint blue is representative of the ways Black people have reconciled that distinct space in our lives. When present in my work, I am using Haint blue as a barrier between Black men's psyches and the racist, immaterial presences that haunt us in the after-life of slavery.

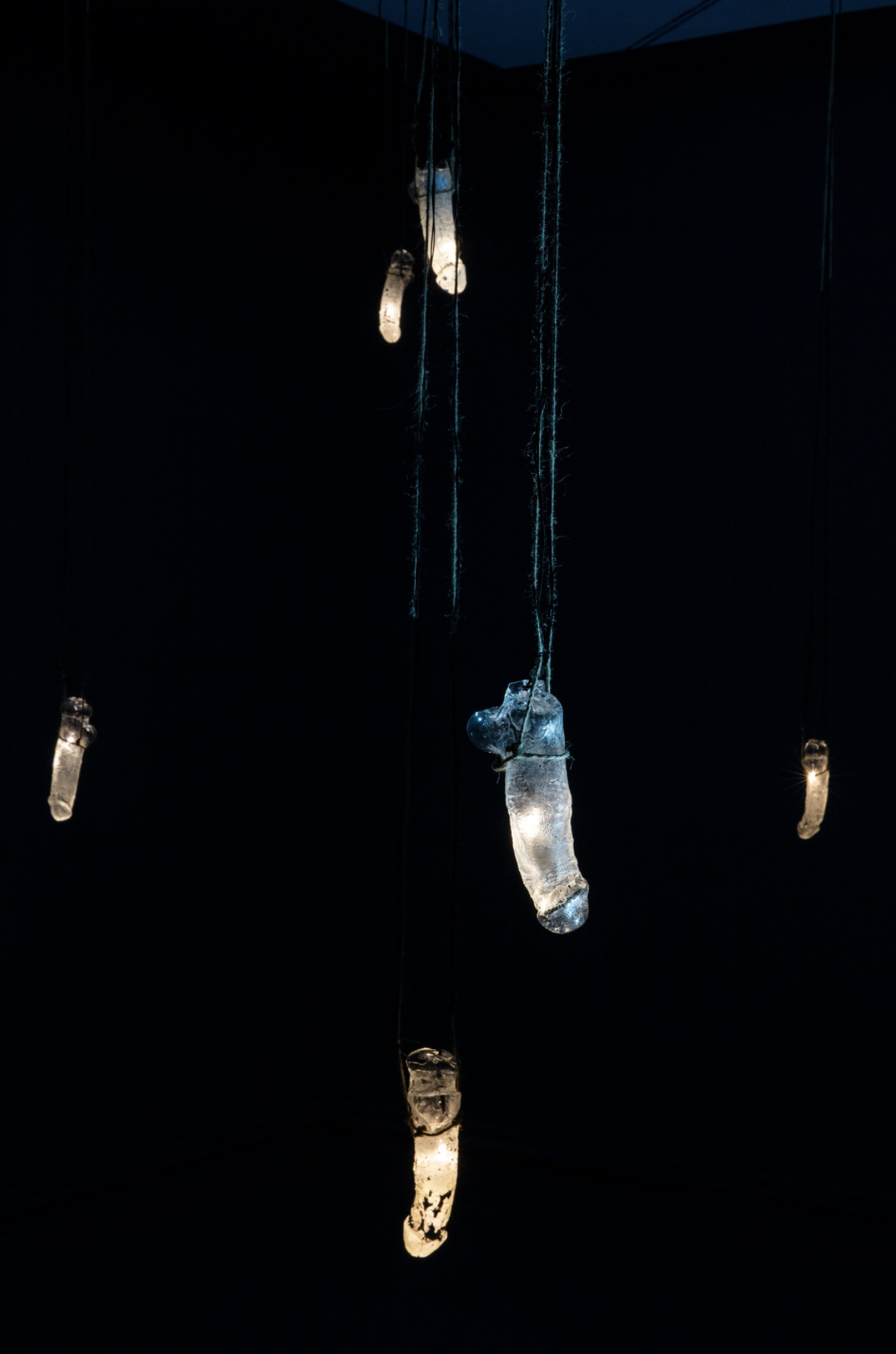

‘notes towards becoming a spill’ (2019), haint-blue paint, LED lights, Audio (30 minutes), Mirrored Glass Sculpture, Mud, Georgia Red Dirt

RS: Similarly, you seem to have developed a visual language within your practice that feels very intentional—Black male figures amongst dirt piles, puddles, reflections. Can you elaborate on this?

S: I'm eager to push Black American visuality boundaries in my art, especially building a palpable vernacular to signify the Black male/queer experience. There was a moment in my artistic development, where I felt restrained to the figurative and the expectations of classifying "Black Art." I leaned into abstraction out of failure, and it allowed me a new pathway of denoting the conceptual ideas I had been struggling to represent in a photograph. It was no longer enough to depict Black queer men as subjects and say this work is a Black queer work. Under those circumstances, I found a symbolic significance in working with what I refer to as these mutable, underground, and fugitive substances and forms such as dirt, spills, and blue light. Notably, working with light brings about a powerful feeling connected to my experience. Growing up, I would often shrink myself to become invisible or fit into the mold of a man laid out before me. Light doesn't adhere to that; it does not shrink itself.

RS: Your figures sometimes feel heavy, as if made of clay or bronze, and other times they’re made of glass, which makes them appear fragile but also transparent. Can you speak to what these decisions aim to do, if anything, about how those bodies are encountered by the viewer?

S: Glass is another one of those materials that carry the Black queer experience's essence because it inherently avoids stasis. This multidimensional realm speaks poetically to what I seek to evoke about the Black male/queer experience. We can be anything we choose to be. We have the right to revise ourselves out of the myths of manhood. Beyond that, we already hold a muscle memory of precarity when considering our human relationship to glass. If approaching an almost 5-foot glass sculpture of a Black male figure or even an 8-inch tall glass balloon, our bodies can't help but feel something similar to a barrier between ourselves in the object. In that pause, there is something that, as an artist, I want viewers who encounter the work to identify.

RS: One of the things I love about your work is how deftly you navigate bringing the viewer into an intimate encounter with Black masculinity. Can you talk about your decision to include breath, oxygen, and sweat as the materials listed in some of the works’ descriptions?

S: I live in a world that seeks to see me and others like me dead. So when an object I make is formed through my body's literal breath, I must note that.

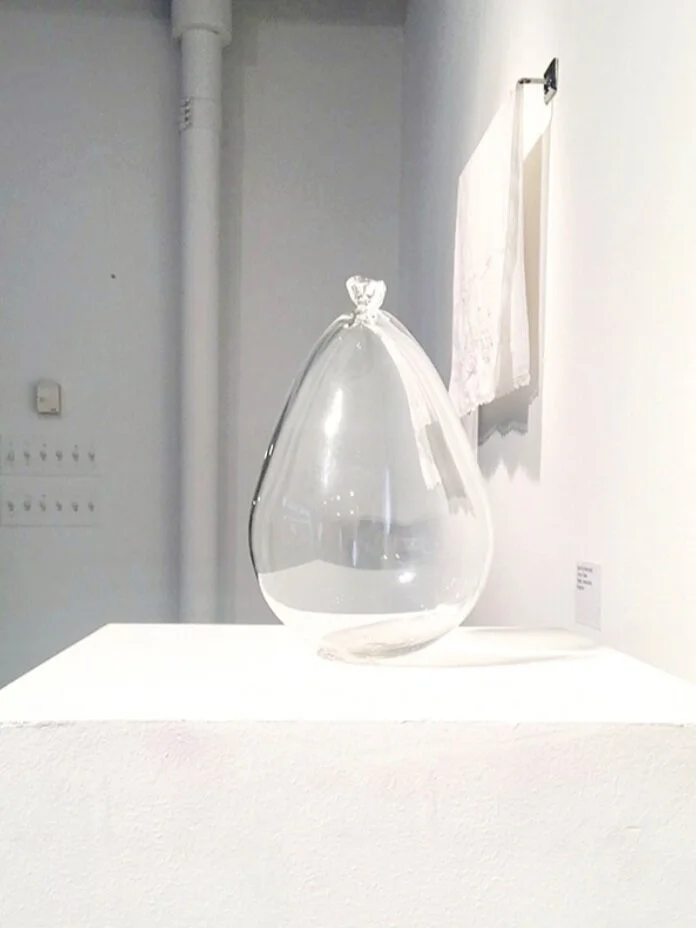

'Undreamed', glass, oxygen, dreams , 2016

RS: Rather than working in a project format, your works seem to all form part of one universe. As if together they iterate on another in building a more and more complex representation of a psyche. Is that an accurate assessment?

S: Yes, that's accurate; I work as if I am filling an entire museum with my work. It's world-building. Everything is connected; there is a throughline with all work coming out of my studio. Focusing on the psychological landscape of black manhood allows for this expansive but specific approach to making.

RS: This conversation is taking place 7 months into the COVID-19 pandemic. Has this time in isolation influenced at all how you’re making or conceptualizing work?

S: I live alone, with not many close friends in the city I reside in, so I have indeed been by myself for the past several months. This experience has undoubtedly poured into the artwork. A couple of months ago, I traveled for the first time during the pandemic to Los Angeles to install a new piece at The California African American Museum of Art entitled "Sermon For A Longing In Blue". With this work, a rendition of Luther Vandross's "If only for one-night" loops inside a narrow dark-brown, tunnel-like space made of wood. It is a rather lonely enclosed space, with no entry and only an arched window as an opening upfront that secretes a deep blue light from inside. Of its various themes, it dwells on the many psychological spaces privacy or insulation can produce, particularly that of fantasy, desire, or even a kind of yearning for intimacy.

RS: What are you into right now?

S: The Keto diet, Brandy's new album "B7", and the classic sitcom "Girlfriends" on Netflix have taken over my life.

RS: What’s coming up for you this next year?

S: I am excited about all the shows approaching, including a new installation opening at MoCA Cleveland in February, but ultimately looking forward to a solo New York City debut in 2021. It will be a significant moment for me! I can't discuss a few more happenings in 2021, but I'm incredibly grateful for what's to come.