Q&A: SHEIDA SOLEiMANI I ON THE IRANIAN REVOLUTION

Originally published on Lenscratch, Nov. 13, 2022

Interview by Vicente Cayuela | November 17, 2022

Sheida Soleimani (b. 1990) is an Iranian-American artist, educator, and activist. The daughter of political refugees who escaped Iran in the early 1980s, Soleimani makes work that excavates the histories of violence linking Iran, the United States, and the Greater Middle East. In working across form and medium—especially photography, sculpture, collage, and film—she often appropriates source images from popular/digital media and resituates them within defamiliarizing tableaux. The composition depends on the question at hand. For example, how can one do justice to survivor testimony and to the survivors themselves (To Oblivion)? What are the connections between oil, corruption, and human rights abuses among OPEC nations (Medium of Exchange)? How do nations work out reparations deals that often turn the ethics of historical injustice into playing fields for their own economic interests (Reparations Packages)? In contrast to Western news, which rarely covers these problems, Soleimani makes work that persuades spectators to address them directly and effectively. Based in Providence, Rhode Island, Soleimani is also an assistant professor of Studio Art at Brandeis University and a federally licensed wildlife rehabilitator.

Sheida Soleimani’s critical tableaux depicting Iranian victims of human rights violations not only evince the brutal fate of countless women and political dissidents. They also illuminate the violence embedded in photographic technology itself. Contemporary and historical practices of surveillance remind us of a hard truth: Photography is not just a record, but a mechanism. “There is something predatory in taking a picture,” Susan Sontag once wrote. In our new machine age, predatory regimes regularly weaponize camera-based technologies to crack down on dissenting voices. As a result, the information we digest of the world, and particularly these regimes, is not simply mediated. It often comes to us highly prejudiced as a product of censorship and bias.

Photography itself can be an act of aggression. Aiming, shooting, distorting and cutting are all violent gestures. With their fascination with dismemberment, Soleimani’s tableaux memorialize fragmented subjects while making tangible the real threat of falling victim to physical, mental, and political subjugations. Any reassortment of photographic fragments is ultimately another Promethean cycle: a torturous investigation of our human preoccupation with destruction and regeneration, captivity and freedom, oppression and revolution. At a moment when photography’s long history of social control and racial, ethnic, gender and political violence is resurgent, Sheida Soleimani’s urgent work reminds us that photography, now more than ever, cannot merely react. It must counteract and steer our collective compass toward justice and, ultimately, freedom.

Vicente Cayuela: I want to emphasize how crucial your work is right now. In the past month, there has been a wave of nationwide protests in Iran following the death of Mahsa Amini—a 22-year-old Iranian Kurdish woman who was violently beaten and arrested after being accused by Iran’s “morality police” of improperly wearing her hijab. Your 2016 series To Oblivion focused on women victims of torture under Sharia Law. Could you extend the message of that series to what is currently happening?

Sheida Soleimani: These issues with this regime, they’ve been going on for so long. The 1979 Iranian Revolution intended to get rid of the Shah’s brutal regime and replace it with a democratic government…. Instead, it spectacularly failed, bringing to power a theocratic, totalitarian dictatorship which is the Ayatollah’s regime. He came in with the promise that he was actually going to allow this freedom for women and there would be no mandatory hijab. Very quickly after coming into power, he went back on all those promises. And the crimes being committed—women being tortured, brutalized, killed under Sharia law for crimes they did not commit—they’ve been happening for the past 43 years, if not longer. They were happening under the Shah’s regime, too. The Ayatollah just happens to be worse.

In National Anthem (2015), I was thinking about human rights violations in general—not just as they harmed women, but also queer people, gay people, trans individuals, and people that could not be themselves under the law of the Islamic Republic without fearing for their lives. Student protesters, anyone speaking out against the government can be brutalized, and even executed. When I made National Anthem, I thought it was really important to act as a medium for the voices of those who are downtrodden and who do not have the freedom to speak about what’s happening to them. But I also realized that something was missing.

©Sheida Soleimani, “Reyhaneh,” from National Anthem

When I made To Oblivion, I was thinking about my own mother and what happened to her when she was in prison and how she was lucky not to be killed. But how many women are killed? How many people are tortured and then executed? I started working with human rights lawyers to get the names of women who had been erased and consigned to oblivion for committing petty crimes, and had been denied a trial. These stories aren’t different from that of Mahsa’s or many other women that have been executed and silenced by the ayatollah’s dictatorial regime.

VC: You’re reacting to these issues very quickly through the dissemination of photographs on the internet, which is an essential component of your praxis. After Mahsa Amini’s death in custody, you made a photograph using sourced images of her. Can you tell me more about its creation process?

SS: It’s been a huge part of my practice. When I started doing Levers of Power in 2020, I started really thinking about what it would mean to react to events as they’re happening and what it would mean to make a practice of reacting to those events by quickly responding and using the images that are circulated on social media. Levers is also simply about finding ways of getting around carefully constructed representations of politicians, and how the depictions of them shape how society reads them and their gestures- both visually and theoretically. For most of Levers of Power, there are US politicians as well as Iranian politicians whose hands are severed from their bodies, which is my way of saying, “Who are the actors here? What are the gestures that they’re making and who’s in power? And are we able to recognize who is who based on how these powerbrokers gesture?”

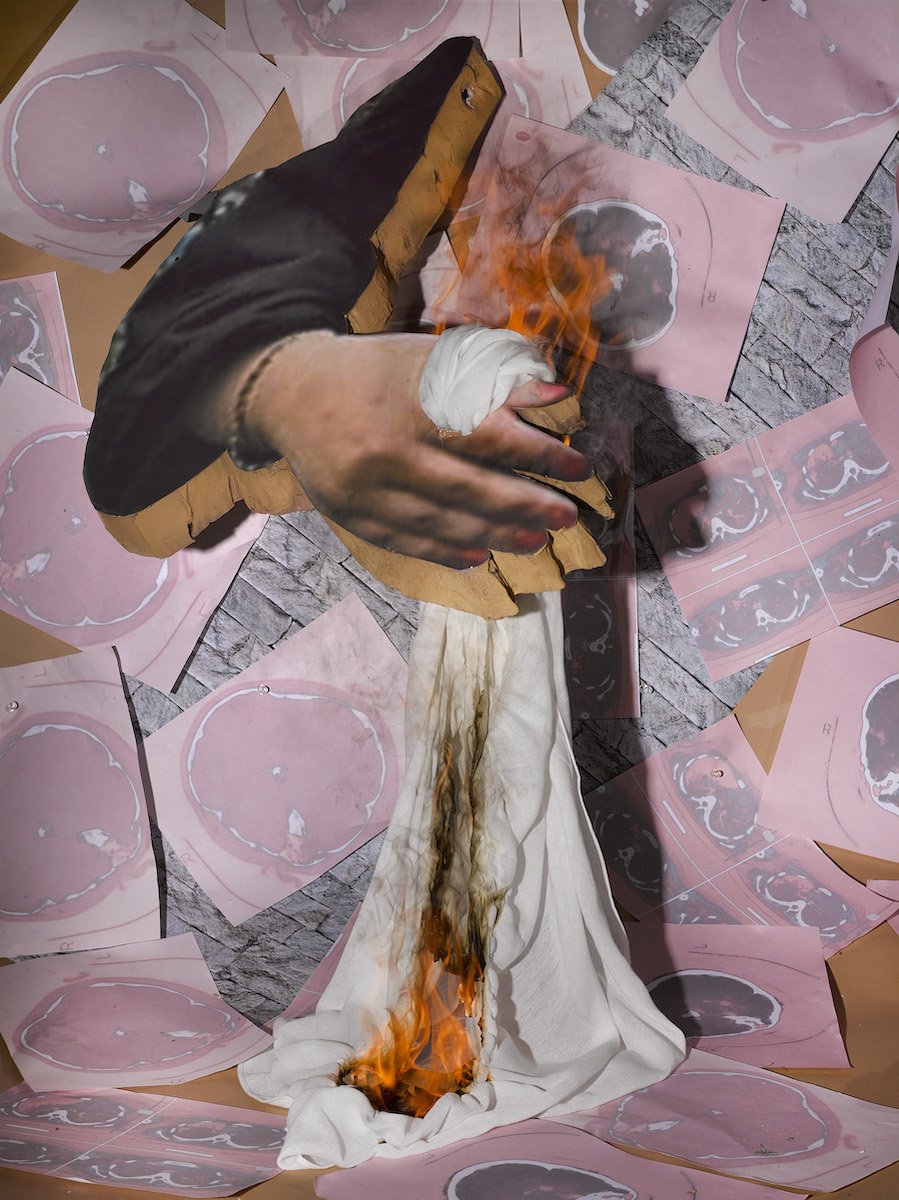

But some of the hands in the images are of victims, as I am considering how they are also part of these narratives and how they are harmed by the politicians in power. For the image of Mahsa, I was thinking a lot about the primary image that was being distributed after her death, wearing the hijab, but with her hair showing, dressed in all black. The hand in the image I made was actually her hand in life while she was still alive. Her hand is grasping a white hijab- a reference to ‘White Wednesdays’: an act of protest that happens every week where women wear white hijabs and then publicly remove their hijabs and either burn them or fly them like a flag on a pole.

The background of the image displays the CT scans of her brain, released shortly after her death. The government for over 43 years now has fabricated lies, saying that people they’ve executed or tortured to death in fact died of natural causes, usually owing to a predisposing condition on the part of the victim. They said that Mahsa Amini just had a heart attack while she was in prison and she died, that she must have had some sort of congenital heart issue. But in her released scans, you see very clearly that there is severe blunt trauma to her head in these images. I wanted to use those as the backdrop for this image to be the proof that we’re not really seeing coming forward from the government. The production of these images says as much if not more about the event than the content of the images themselves.

VC: Are there any other instances in Levers of Power that include an individual that has been persecuted by the Iranian state?

SS: Right. The series has two hands in it that are of victims, not the “governmental actors.” Ruhollah Zam was an activist that ran the progressive news station called Amad News. He was executed after being lured back into Iran by the government, and once captured was charged with conspiring to bring down the government, under Sharia law the crime is actually known as “Conspiracy on Earth”. In the image, you see two hands, connected by a Molotov cocktail. Part of Zam’s “conspiracy” was giving information to activists on his site on how to make a Molotov Cocktail for protests.

VC: Widespread control of political dissent is something that extends to the censorship of the arts and culture. Can you talk about Iran’s Ministry of Guidance, its role in “cleansing” cultural production, and how this has led Iranian artists to resort to self-censorship?

SS: First of all, I think there’s one distinction that should be made; I’m very lucky to be making the work that I am making, and I am able to do so because I’m not in Iran. I have the ability to talk about topics that many Iranian artists would like to, but are unable to. They have to self-censor, and they have to think about symbolism as a way to code their messages. The use of no-transparent symbols is something many westerners don’t appreciate or spend time with when it comes to the work of Iranian artists. Americans very much expect things to be right on the nose and to tell you exactly how to feel and how to believe in something. Iranian artists, writers, and creatives do not have that ability, because the minute that they speak directly about a political issue, they’re signing a death wish. Symbolism has been a means by which Iranian artists have represented political ideology in their work without having to explicitly express their views. The history of censorship within the country has created the need for alternative visual languages.

VC: Can you share with us some of the consequences your criticism of Iran has had on your personal life?

SS: Absolutely. Even outside of the country, Iranians in the regime do not want to see what they would call “misinformation” spread about their regime. If someone is saying that the Iranian government hurts women or that the Iranian government doesn’t believe in equal rights, if you actually are an outspoken voice and you have a presence on the Internet, members of the Basij, a paramilitary group will be very quick to respond.

After making To Oblivion…that was the first time my work really had gotten publicized. I had a lot of death threats. Phone voicemails were left actually at Brandeis as well as RISD, where I was also teaching at the time. These people will stop at nothing. There’s a long, long history of Iranians that are working as agents of the government who leave the country to assassinate outspoken individuals.

VC: Control over women’s autonomy is expanding to the digital sphere under the presidency of Ebrahim Raisi. An order was issued recently stating that government employees will be fired if their images on social media do not comply with Islamic laws; while “violators” of the new restrictions will be fined or lose social benefits if they share photos of themselves without a hijab. How does your work address the weaponization of information technology as a surveillance mechanism in authoritarian regimes?

SS: Iranian state run internet is saturated with propaganda. Iranians can’t find real-time information unless they have a ‘filter-shekan’ (filter breaker) or a way to bypass the state sanctioned web. Iranians are also living in a surveillance state. We’re sitting here worried about Amazon giving us too many ads on our phones and being like, “Oh, my God! I can’t believe that my phone is showing me these shoes that I looked at on this other website! I feel like I’m being controlled!” It’s true. We all are being watched and our data is being tracked, but it’s very, very different. Citizens living under totalitarian rule don’t have the worries about data surveillance feeding their consumer tastes in the ways that we do in the west. Instead, they have to be concerned about what they post on their social media pages, what they say on private phone calls, and the websites and information they are looking at in case they are being watched. In a lot of ways, this has promoted a culture of silence among Iranians, because that has been a mode of survival. If you are silent, at least you’re safe. But I think it’s also reached a boiling point. Women and people are not willing to be silent anymore because they’ve wanted change for so long.

VC: It is imperative that technology allows people to participate in public discourse and instigate social change. Just recently, Iranian authorities announced the use of facial recognition technology in public transport to impose new hijab laws. The power structures in the genetic code of surveillance technology, and the very development and implementation of these tools, are rarely democratic. According to you, who are we in the eyes of the machine?

SS: The usage of facial recognition software in Iran is very different in the way that it is being used here in the states. When it comes to the Iranian government, facial recognition is being used to try to match the identities of protesters with actual images. If someone’s image is recorded during a protest, the Basij, the paramilitary, will go out in a protest and they’ll start taking photos of people. Then they will put the photos on a website and offer a bounty for the names of these people. They’ll circle the faces that are apparent and they’ll say, “if you know who this person is, we’ll pay you this much money to tell us who they are, and we could find them and imprison them.”

Because of the sanctions and the financial situation in Iran, a lot of people are unfortunately taking that incentive. They’re saying, “we’d rather have money for our family to be able to eat. We don’t care about this person. We’ll sell them out to the government.” Facial recognition software is also very much being used in that way. No matter where you go if you’ve participated in something, you’re being tracked. You’ll see that a lot of the protesters are actually wearing masks – not for covid purposes, but for the ability to protect their identity.

Are we all one or individuals under the face of the machine? I think it depends on where you live. I really do. I think it depends on the government that is policing your nation. But I don’t know. I don’t really think of us as ‘individuals’ here either. I think of us as a collective. The ongoing Iranian revolution is about individual rights, but it’s also about how we as individuals are part of a larger whole and are voicing dissent. That’s where the power is—with the people.

©Sheida Soleimani, from Ghostwriter

VC: There is one question that I’ve been wanting to ask you since I saw your work on the cover of the Boston Art Review. You have started exploring your family’s history more explicitly, including your parents in your sets for the first time in your series Ghostwriter. What has been the most challenging aspect of taking on this more autobiographical lens?

SS: I think the ethics of it. I mean, you know, you’ve seen me in a classroom setting. Thinking about how I teach photography, I think about the body and if it is ethical to photograph it in any way, shape, or form. Through what “lens” are we looking at the body? Thinking about our societal conditioning, how are we conditioned to treat race, gender, class, all of these things? If I am putting my parents in front of my lens and then showing their image to the world, and then opening that up for them to be racialized or identified in some way they aren’t supposed to be classified, I don’t have control of that conversation. There are a lot of moves that I have made and things that have been done to kind of help prevent that. Obviously, the masking is partially to protect their identity, because my parents still need to protect their identities for political reasons.

It took me a really long time to do this because it’s not that I wasn’t ready to go there. It’s that I wasn’t ready to put it into the world because, after almost a decade in the art world, I very quickly realized that any time the narrative about my family comes up, it becomes clickbait. These stories are so much more important than that, and they deserve more. I wasn’t ready to do that to my parents because I didn’t have the language to frame it. I didn’t have the position that I do in the art world now. I didn’t have the community that I do now. I think after so long I was ready to be like “Okay, you know what? I know how I want to frame it. I know who I’m going to talk to about this, and I know who I’m not going to talk to about it. If someone asks me these questions, I know exactly how I’m going to respond now. It’s taken a very long time to get there.

Works Cited

Sontag, Susan. 2008. On Photography. London, England: Penguin Classics.

VICENTE CAYUELA’S BIO

Vicente Cayuela is a Chilean multimedia artist, cultural worker, and editor working primarily in research-based, staged photographic projects. Inspired by oral history, the aesthetics of picture riddle books, and political propaganda, his complex still lifes and tableaux arrangements seek to familiarize young audiences with his country’s history of political violence.

His 2022 debut series “JUVENILIA” earned him the Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the Saint Botolph Club Foundation, a Lenscratch Student Prize, an Atlanta Celebrates Photography Equity Scholarship, and a role as a photography juror for the Alliance for Young Artists & Writers' Scholastic Art and Writing Awards in the Massachusetts region in both 2023 and 2024.

His work has been exhibited most notably at Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, the Griffin Museum of Photography, Brandeis University 75th Anniversary Alumni show, and published nationally and internationally in print and digital publications, including Analog Forever, Alt’iba 9 Contemporary, and Fraction Magazine.

As a cultural worker, Isaías has conducted interviews with renowned artists and curators, directed various multimedia projects for notable photography exhibitions, and provided photographic services for exhibitions, events, books, and catalogs across a range of museum platforms and art publications. His contributions have supported significant solo, group, and retrospective exhibitions such as Frida Kahlo: Pose (2021) and My Mechanical Sketchbook: Barkley Hendricks & Photography (2022) at the Rose Art Museum, Marc Swanson: A Memorial to Ice at The Dead Deer Disco at TCNHS/MassMoCA (2022), and Women Reframe American Landscape (2023) and Thomas Cole's Studio: Memory and Inspiration (2022).

As the Latin American Editor for Lenscratch Fine Art Photography Daily, he has reviewed several photography exhibitions and collaborated with contemporary art galleries specializing in photography. He has also edited several contemporary spotlights on various countries, including Mexico, Argentina, and his home country.

He earned a BA with High Honors in Studio Art from Brandeis University, where he was awarded the Wien International Scholarship for the years 2018 to 2022, and received both the Deborah Josepha Cohen Memorial Award in Fine Arts and the Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography upon graduation.

Follow Vicente on Instagram: @vicente.isaias.art

Follow Soleimani on Instagram @sheidajanam

Website: www.vicentecayuela.com

All images © Sheida Soleimani