Q&A: Gazelle Samizay & Labkhand Olfatmanesh / The High Wall

By Rafael Soldi | Published October 7, 2020

Interview conducted August

2020Strange Fire Collective is partnering with the High Wall to present interviews with the High Wall’s 2020 featured artists.

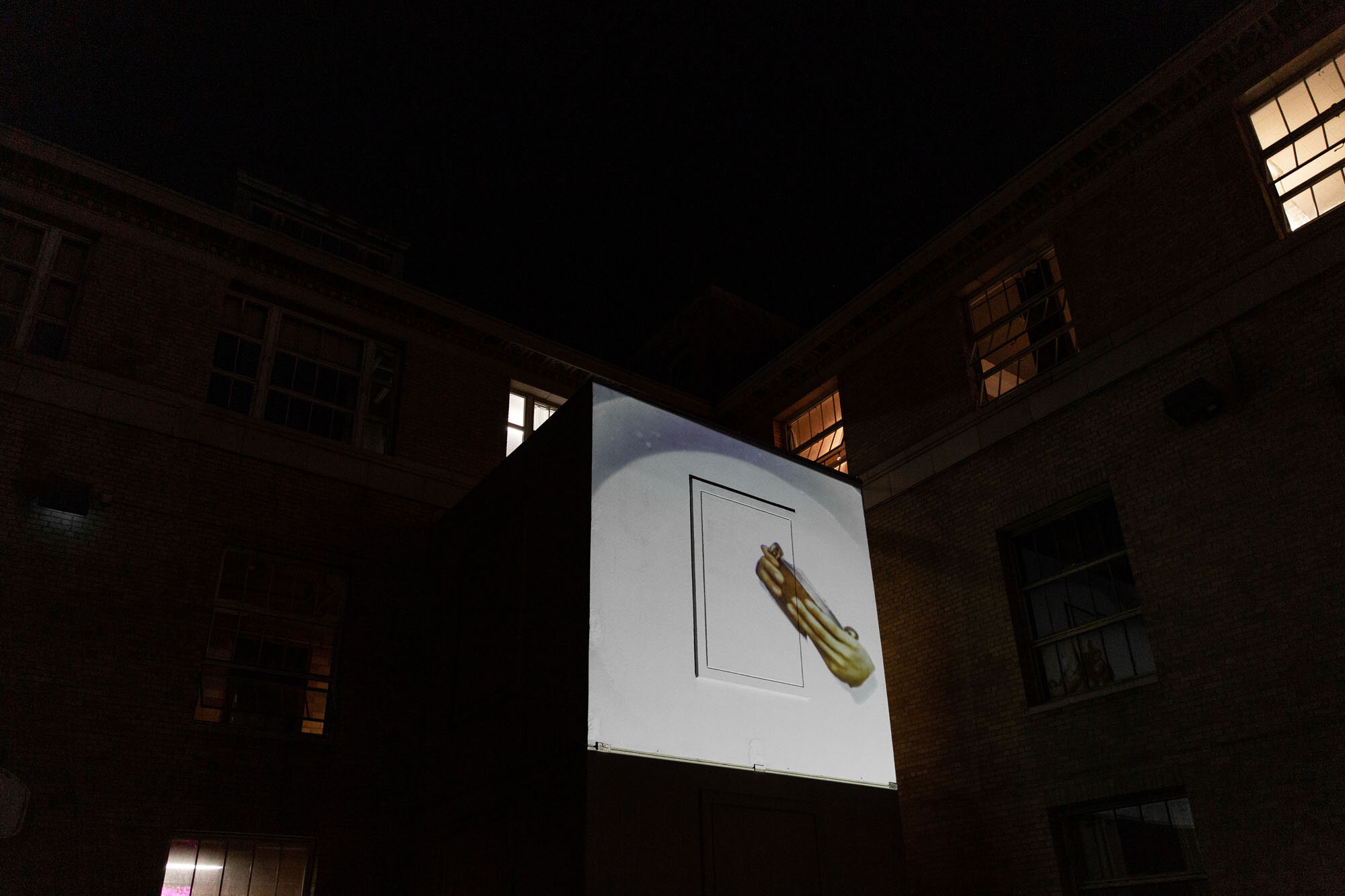

The High Wall is an outdoor video projection project at the Inscape Arts Building in Seattle, WA. Honoring the building’s complicated history as an immigration station, the High Wall aims to show the work of artists who are immigrants or working with themes of immigration, borderlands, and diaspora.

Every year the High Wall invites three artists to create an intervention on the building’s facade—a public video projection visible from multiple public spaces. The works were on view August 13-16, 2020. The High Wall is co-curated by Britta Johnson and Rafael Soldi; here we present three conversations between the curators and each artist/artist team:

Alice Gosti

Nadia Ahmed

Gazelle Samizay & Labkhand Olfatmanesh (below)

Born in Kabul, Afghanistan and raised in rural Washington state, Gazelle Samizay’s work often reflects the complexities and contradictions of culture, nationality and gender through the lens of her bicultural identity. Her work in photography, video and mixed media has been exhibited across the US and internationally, including at Whitechapel Gallery, London; Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery; the California Museum of Photography, Riverside; the South Dakota Museum of Art, and the Slamdance Film Festival, Park City, UT. Her pieces are part of the permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Center for Photography at Woodstock, NY; and En Foco, NY. In addition to her studio practice, her writing has been published in One Story, Thirty Stories: An Anthology of Contemporary Afghan American Literature and she is a project leader in the Afghan American Artists’ and Writers’ Association. Samizay has received numerous awards and residencies, including from the Princess Grace Foundation, NY; Craft Contemporary, Los Angeles; the Arizona Community Foundation, Phoenix; and Level Ground, Los Angeles. She is currently an artist-in-resident in FORUM at the Torrance Art Museum. She received her MFA in photography at the University of Arizona and currently resides in San Francisco.

Labkhand Olfatmanesh is a multidisciplinary artist examining topics of feminism, race, and isolation. Her works explores how these forces take dual shape as an immigrant to the United States and in her home country of Iran. Her recent photo and video work has been exhibited in group and solo exhibitions including Photo London U.K.; Rencontres d’Arles, France; Craft Contemporary, Los Angeles; 4 Culture, Seattle; FestFoto, Brazil; POST Gallery; the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery; and the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco. She has been awarded high honors from The Los Angeles Center of Photography (First Place, 2018) and LensCulture (Jurors Pick, 2018), among others. She earned a B.A. in graphic design at Azad University in Tehran, Iran and a Photography Certificate in 2006 at the London Academy of Radio, Film, and Television. Her work has also been featured by the United Nations, the British Council, and Australian High Commission (2005) as well as at the Peace of Utrecht Festival, Netherlands (2006) and in the UNESCO Palace, Lebanon (2006). She was also a member of The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ). Currentl, She is member of collective leadership team at Level Ground in Los Angeles, CA

Rafael Soldi (RS): Hi Gazelle and Labkhand, thank you so much for taking the time to chat with us! Maybe a good place to start would be to learn about how you two first met and what’s the story behind your ongoing collaboration.

Gazelle Samizay / Labkhand Olfatmanesh (GS/LO): We met in 2017 at a group exhibition at the Craft and Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles. We became friends and decided to work on a collaboration. We were interested in the overlaps in our experiences as women who came from neighboring countries and ended up in the US. This exploration led to the video “Bepar (Hop).” Employing the common cultural reference of hopscotch (named “lay lay” in Iran and “joz baazi” in Afghanistan), the protagonist in the video relives the personal and political moments of her past, such as war, marriage, generational trauma, and gendered social expectations. The particularities of our experiences as women of Afghan and Iranian heritage fed our collaboration, though Gazelle Samizay grew up in the US and Labkhand Olfatmanesh grew up in Iran, allowing us to create a universal story rooted in specific cultural intersections.

After completing “Bepar” we continued to work with photographs, objects and video in order to push some of the themes touched on in “Bepar.” This led to the series “Woven,” of which “Undercurrent” is a part.

Britta Johnson (BJ): Can you talk about the photograph in the piece? Are the hands holding a personal object, or something more universal?

GS/LO: “Woven” takes printed images from “Bepar” and reconfigures them in new ways. Bodies are fragmented and images are repeated by photographing and filming prints in different configurations, reflecting the transmutation of memories or trauma. In “Bepar” the scene where the protagonist picks up a copper bowl and looks inside it is symbolic of looking toward her future—it is a moment of self-reflection and hope. Labkhand purchased this handmade bowl on a return visit to Iran. In “Undercurrent” we take this symbol out of its original context by cutting it out of the printed still and submerging it in another bowl of water. Instead of the main character looking into the bowl, we as the artists do, understanding fate from a different angle. Fate plays a large role in Afghan and Iranian culture. It is often used to explain the things outside of our control, and as such, can be seen as both benevolent and merciless. But it also puts into question our agency and our abilities to shape our futures, especially as women.

Like the water that seems to emanate from the copper bowl, the idea of fate is both powerful and mesmerizing. The transition from the water bubbling to it being still and then dropping toward the bowl represents past, present and future. As if recalling a distant memory, the sound emerges faintly and intermittently, but then rushes in as a flood. This is followed by a moment of calm stillness and then the motion continues forward.

RS: As two artists from neighbor nations in the Middle East, there must be both common ground and inherent differences in your experiences. Can you talk about what you each bring to your collaboration, how your shared experiences may coalesce conceptually, and how your individual perspectives may complicate or bring nuance to your collaborative work?

GS/LO: Together we create work that expresses the intersection of our upbringings as women from similar (and different) backgrounds. Our individual working styles have complemented each other to bring out new experimentation and ideas for each of us. For example, Gazelle tends to work slowly and methodically, while Labkhand works more spontaneously. We have grown as individual artists by learning from one another’s approaches.

RS: I’m curious about the title of the piece, why “Undercurrent”?

GS/LO: We thought “Undercurrent” was a fitting title because it implies that there is one thing happening on the surface, and something hidden beneath. We see the idea of fate as a powerful underlying influence in the lives of many Afghans and Iranians, but we question whether this idea empowers people to forge their own paths.

RS: How does this piece sit within your larger body of work, both as collaborators and individually? Is this a stand-alone piece or part of a larger exploration?

GS/LO: “Undercurrent” is part of the series “Woven,” which builds on our video “Bepar.” We manipulate photographs into layered or 3D forms, a new process of experimentation in both of our practices. The collages are experiential—the viewer discovers different details depending on the viewing angle. This resists a facile consumption of our identities, thus challenging stereotypes of women from the S.W.A.N.A region. The multitude of elements in each piece reflects the confusion and conflict we feel as citizens of the U.S., a nation that inflicts violence on our home countries in the form of war, occupation and economic sanctions. Through this process we gain a better understanding of one another as women from sister countries, while exercising power in the way we know how, as immigrants living in the land of our colonizer.

BJ: Thanks so much to both of you for sharing your thoughts about your practice and this piece!