Q&A: Roula Seikaly

By Rafael Soldi | May 26, 2022

Roula Seikaly is a Berkeley-based independent writer and curator, and Senior Editor at Humble Arts Foundation. Her curatorial practice addresses photography and New Media, social justice efforts in contemporary art and exhibition making, and institutional critique. Her writing is published virtually and in print on platforms including Hyperallergic, Photograph, BOMB, and KQED Arts. She has curated exhibitions at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, SOMArts, SF Camerawork, Blue Sky Gallery, Filter Photo, Colorado Photographic Arts Center, and Photographic Center Northwest. She is the co-recipient of Blue Sky Gallery’s 2019 Curatorial Prize for the exhibition An Inward Gaze. In 2021, she was named Curator at the NFT platform Quantum Art.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Roula, thanks for joining us.

Roula Seikaly: Thank you for having me, and thank you for taking an interest in All of Us All of Us! Historically, I've been in the interviewer's chair for Strange Fire Collective, and I'm so excited to be on the other side.

Soldi: All of Us All of Us, an exhibition curated by you, is currently on view at the Berkeley Art Center. How did this show come to be? What made you want to highlight contemporary projects born of collaboration and mentorship?

Seikaly: In August 2021, Kimberley Acebo Arteche, one of my dear friends and Bay Area art colleagues who is also co-director of Berkeley Art Center (BAC) invited me to curate an exhibition. I've visited this space in north Berkeley many times in the nearly 14 years that I've lived in the Bay Area, and was thrilled to receive the invitation to contribute to its programmatic history.

As a creative practice, collaboration in various forms is something I've been thinking and reading about for a few years. A lot of attention is paid to photography as a solo practice, particularly in the western Modernist/20th century chapter of the canon's history. I want to know more about who made or is making work that undermines the solo, usually white-male-cis-hetero model. Understanding collaboration as a photographic practice fills gaps in my art historical knowledge and, much more importantly, how often (but not soley) under-represented artists (queer, BIPOC, trans, women, socio-economically disadvantaged) in the art world navigate various systems that are designed to exclude them.

Soldi: I'm not from the Bay Area. I'm curious if you think this collaborative way of working, or these artists in particular, in some way reflect the spirit of the Bay Area—its culture, its history, its attitudes, this very moment? Or would you say that they rather mirror something happening on a much larger scale, nationally or globally?

Seikaly: Collaboration as praxis certainly isn't exclusive to the Bay Area art community, but I do see a lot of projects produced that way. The Bay Area arts scene, unlike those in Los Angeles and New York and many located in major cities outside the United States, is often thought of as inward-facing or provincial. I don't agree with either of those assessments, but I mention it here because an "inward" could be interpreted as "community," and that could factor into why collaborative projects tend to flourish here. I regularly witness collegiality and enthusiastic support for what peers are doing, and/or what they've accomplished. People are curious about what others are involved in, and they want to participate. I think that's been true of artists working in this part of the world for decades. So, answering your question more directly, yes, I think collaboration is baked into the history and contemporary culture of the Bay Area arts community. On a national or global scale, I think collaboration as what we now call "social practice," and specifically social justice practice in art, has a long history, and is receiving well overdue attention institutionally.

Soldi: The collaborative threads are not the only concept governing your selections, you've also chosen to center representation, agency and community in contemporary art practice. Can you expand on these aspects of the show as well?

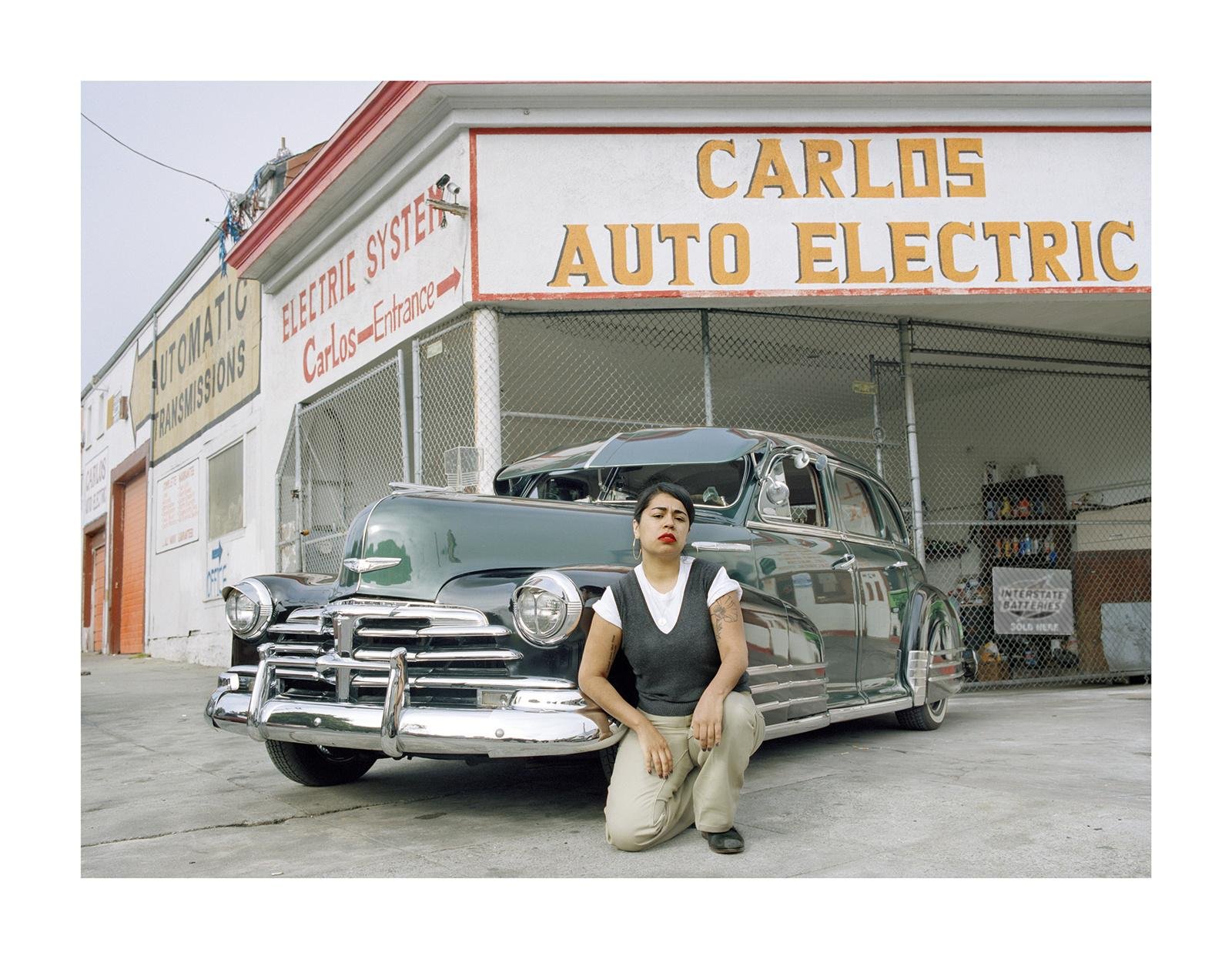

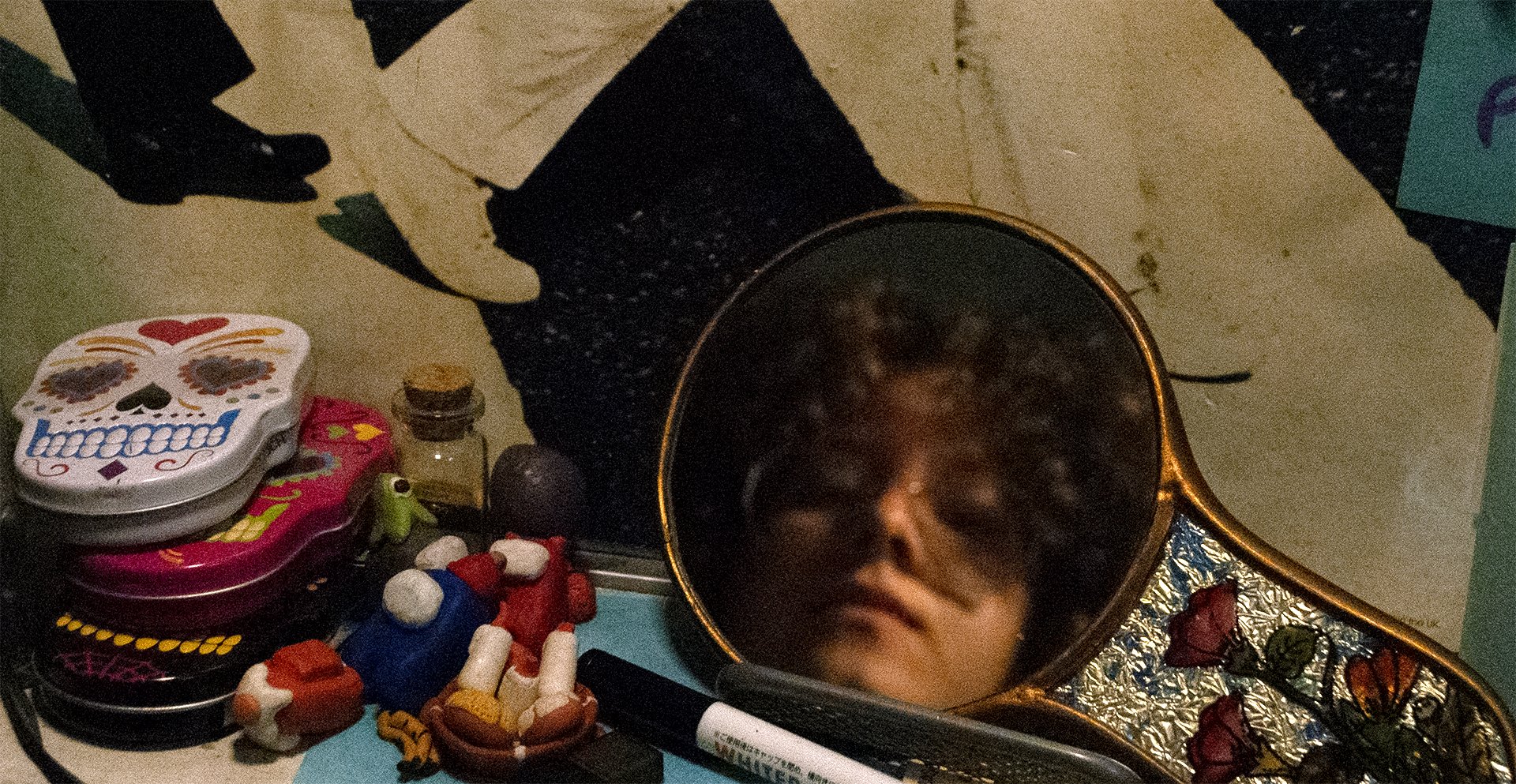

Seikaly: Absolutely! Photography was popularly touted as a democratic art form from the end of the 19th century onward. That may be true from a narrow economic and access perspective, but from a representational point of view, that's not true. There are gaping holes in the medium's history for anyone who wasn't white and heterosexual. That has everything to do with which perspectives are emphasized in that history, and who is shaping it institutionally in books and exhibitions and market sales. Contemporary projects such as Tristan Crane's Here, Marcel Pardo Ariza's Una Linda Realidad, and The Q-Sides acknowledge that selective representation, and beautifully trouble it by simply being. Which gets to the second part of your question regarding agency and community. Agency isn't requested. It is joyfully and righteously seized by these artists and their collaborator-sitters. Permission isn't expected or sought, either. While these projects are more widely experienced in an exhibition context such as All of Us All of Us, what's most important is that they are seen by the queer and trans communities as further signal that representation is accessible.

Soldi: What was your process for researching the exhibition and assembling your artists? Have you worked with any of these artists before? Are all the works existing or were any of them commissioned?

Seikaly: I interacted with most of the artists prior to curating All of Us All of Us, primarily as a writer. I interviewed First Exposures Executive Director Erik Auerbach and then-Program Associate C.A. Greenlee for Humble Arts Foundation in 2016. I deeply admire the organization, and have volunteered for their annual fundraising event Looking Forward, Giving Back a few times over the years. I've reviewed exhibitions of Marcel Pardo Ariza and Kari Orvik's work for Photograph and KQED Arts respectively. I didn't know Kari's co-creators Vero Majano and DJ Brown Amy before starting this project, but had seen The Q-Sides installed at San Francisco's Galerie de la Raza in 2015. I met Tristan Crane during a CatchLight portfolio review in 2019. All of these projects were extant, though Marcel's Una Linda Realidad wasn't in production just yet. It was a pleasure to present new work, none of which would have happened without the help of their gallerist Aimee Frieberg of Cult Exhibitions.

In thinking about collaboration, I knew I wanted to represent the concept as broadly as possible, while also honoring the exhibition space parameters. Collaborative and environmental portraiture quickly emerged as a theme. I settled on work by First Exposures mentors and mentees so as to think about collaboration from an educative perspective, what each participant may learn from the person they are paired with, and how those connections often outlive the time the mentees are enrolled in the program.

Soldi: The exhibition also primarily displays portraiture. As we're all exiting our pandemic bubbles, human interaction and sharing space is at the forefront of our collective psyche. How do you think this strange moment in time mediates the viewing of an exhibition that centers people and portraiture?

Seikaly: As an existential moment, I think Covid commanded a reckoning with what we value, how and where we live, and the systems that do or don't work for us. I think, I hope, it has made us more reverent of life's fragility and temporality. I hope it has rendered us kinder when looking at or interacting with others, even though this country is more violently divided than it's been since at least the height of the Civil Rights era. I hope All of Us All of Us is one among many experiences audiences have - as something resembling life's normal or familiar pre-Covid rhythms resume - that nurtures a love of humanity and its variety.

Soldi: Many of the artists involved form unexpected partnerships, what are some of your favorite elements that resulted from these collaborative opportunities? Do you think any of these models can be fruitful for other artists as well?

Seikaly: Listening to Kari, Vero, and DJ Brown Amy speak recently about the musical compilation East Side Story as cultural touchstone and the inspiration for their project was powerful. DJ Brown Amy co-founded Hard French, a monthly queer soul party in San Francisco, and to my knowledge had never participated in a visual art project before The Q-Sides. While it's not an unexpected partnership per se, I love how her soul music knowledge helped shape this project and how it influences queer, Latinx, and lowrider culture in the Bay Area rhizomatically. As to a model for other artists, I'm all in favor of cross-disciplinary projects. Anything that extends the reach and impact of art (visual, literary, musical, theatrical, etc.) is a good thing.

Soldi: I find that when I work on projects, oftentimes they lead me to the beginnings of the next one. Sometimes they crack open the door into another topic I wouldn't have found otherwise. Is there anything you discovered along the way here that you're looking forward to diving into further?

Seikaly: As it turns out, All of Us All of Us was happily influenced by another project I'm working on that was in progress well before Kim invited me to program BAC. Two curators I admire—Kevin B. Chen and Sharon Bliss—invited me to work on an exhibition at SF State University that celebrates nonbinary representation in contempoary art. In organizing Beyond Binary, which will open in the Fine Arts Gallery on September 18th, we intentionally sought out work that's not photographic. Working on these exhibitions in tandem has exposed me to exceptional visual art, and clarified the privilege of representation afforded me as a white-passing cis hetero woman, and how to interrogate it effectively.

Soldi: Thank you Roula!

Seikaly: Thank YOU, Rafael!