Q&A: Richard Renaldi

By Jess T. Dugan | December 10, 2015

Richard Renaldi was born in Chicago in 1968. He received his BFA in photography from New York University in 1990. Exhibitions of his photographs have been mounted in galleries and museums throughout the United States, Asia, and Europe. In 2006 Renaldi's first monograph, Figure and Ground, was published by the Aperture Foundation. His second monograph, Fall River Boys, was released in 2009 by Charles Lane Press. Renaldi's most recent monograph, Touching Strangers, was released by the Aperture Foundation in the spring of 2014. In 2015 Richard was named a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow in Photography.

Jess T. Dugan: Your photographs really need no introduction; you are such a prolific photographer and you’ve had a huge year with the publication of Touching Strangers and your recent Guggenheim Fellowship. But, to begin, could you tell me a little bit about your work? What drives you to photograph?

Richard Renaldi: Thank you Jess. I suspect my work is derived from both looking outward into the world and exploring my own personal histories. I use landscape, portraiture, and storytelling to filter my ideas into cohesive bodies of work that I approach with a sense of humanism, humor, and sensuality. I am driven to photograph by being in the world. By that I mean observing the things I find attractive and having an impulsive and intuitive response to photograph them. I love looking and I think it’s something I learned to do as a young person having developed an affinity for art and photography from an early age. Combining those qualities with a passion for traveling has resulted in a rather extensive archive as you might imagine.

JTD: I have always loved your Hotel Room Portraits. I find them incredibly moving, primarily because of the consistency of you and Seth being together in locations across the globe, over a time period spanning more than a decade. Can you tell me more about this series? When did it begin? What is your process for making these photos? Do you have plans for its completion, or will it be a never-ending project? Do you view it as having a political element?

Chincoteague, Virginia, 1999- Hotel Room Portraits

RR: The first Hotel Room Portrait I made was in Chincoteague Island in Virginia in 1999. The picture from Chincoteague was really a result of just messing around and there was no intended purpose to making that picture but because the photo had value and feeling we soon started to incorporate making self-portraits into our travels together. Before long it was a “thing.” Our relationship together is now in it’s eighteenth year and I would estimate for the first ten years our approach was far more casual. Sadly there are quite a few missing locations from the early travels we made together. When we purchased our first DSLR in 2007 a visible shift occurred. We became more disciplined and serious about making a portrait every time we traveled and the technical quality greatly improved. We also started to travel with a tripod and Seth become more involved in the set up and quite often he kept the enthusiasm going even when I didn’t feel like it. Seth’s background is as an architectural photographer so this project is really a perfect merging of my enthusiasm for portraiture and his for architecture.

Casablanca, Morocco, 2014- Hotel Room Portraits

This year was quite a big year of travel for us having done some extensive excursions in East Africa, South East Asia, and Eastern Europe and the hotel count for 2015 is at a whopping sixty-one. As you suggest I suspect it is a “never-ending” project. I think it will imbue itself with more meaning as the passage of time goes onwards and onwards.

Do I view the work as having a political element?

One could argue that every public act as an out gay person is a political act but I ‘d prefer to think it has more of a human element. I believe that a view of two men together in a long-term relationship can be as equally affirming to heterosexuals as it is to homosexuals.

Thailand, Vientiane- Bangkok, 2005- Hotel Room Portraits

I think that by sharing these self-portraits of the two of us amongst the many different classes of hotels, motels, and resorts where we have stayed, and by doing so year after year does stand for something. That very well might have a political component to it but we prefer to let that be more ambiguous than to name it.

The work however has been featured on several gay websites over the years including the Advocate and without taking user comments too seriously it being the Internet after all, a criticism that has been oft repeated is one regarding our race. People have suggested our whiteness was uninteresting or an issue for them. It’s something I really don’t know how to or if it even needs responding to…

Ashtabula, Ohio, 2012- Hotel Room Portraits

JTD: Much of your work is about a chance connection, about going out into the world and seeing who and what you can find. Have you always worked this way? What is it about these chance encounters that you find exciting and meaningful?

RR: I started working this way when I was photographing the predominately gay and lesbian scene down at the Christopher Street Piers in the early 1990’s. That project Pier 45 really made me comfortable with approaching strangers and making a series of portraits of a subculture that I was both a part of and an observer to. I like engaging with strangers and I think my personality, which is more extroverted and outgoing, is well suited to these types of encounters. I feel pretty at ease walking up to a stranger and I do find value in sharing a moment with someone I do not know. I am however not terribly adept at interviewing or questioning my subjects and think I could push harder to find out more personal information. Maybe that is because I am more focused at that point on the set-up and making of the photograph but I suspect I have inherited a slightly bigger larynx than eardrum regarding my conversational aptitude.

JTD: To what extent is your work influenced by your identity as a gay man? Obviously this is more present in some work, such as the Hotel Room Portraits, and perhaps less so, or to a more subtle degree, in other projects, such as Manhattan Sunday or Fall River Boys.

RR: I think my identity and experience as a gay man has had a great deal of influence in my work. I would counter that in Fall River Boys a major theme that I was exploring was young male machismo. That is a characteristic as a gay man that I have certainly been propelled towards. Manhattan Sunday may in fact be my most autobiographical work. My first boyfriend Terry was a DJ, my next boyfriend Eric and I were regulars at the legendary Sound Factory in New York, and after Eric there was David who was a go-go dancer. The club served as a surrogate for acceptance and community outside of the mainstream morals. I have tried to make that experience of being out all night in the fog and blur of the nightclub and entering into the solitude of empty city as both a personal and universal experience.

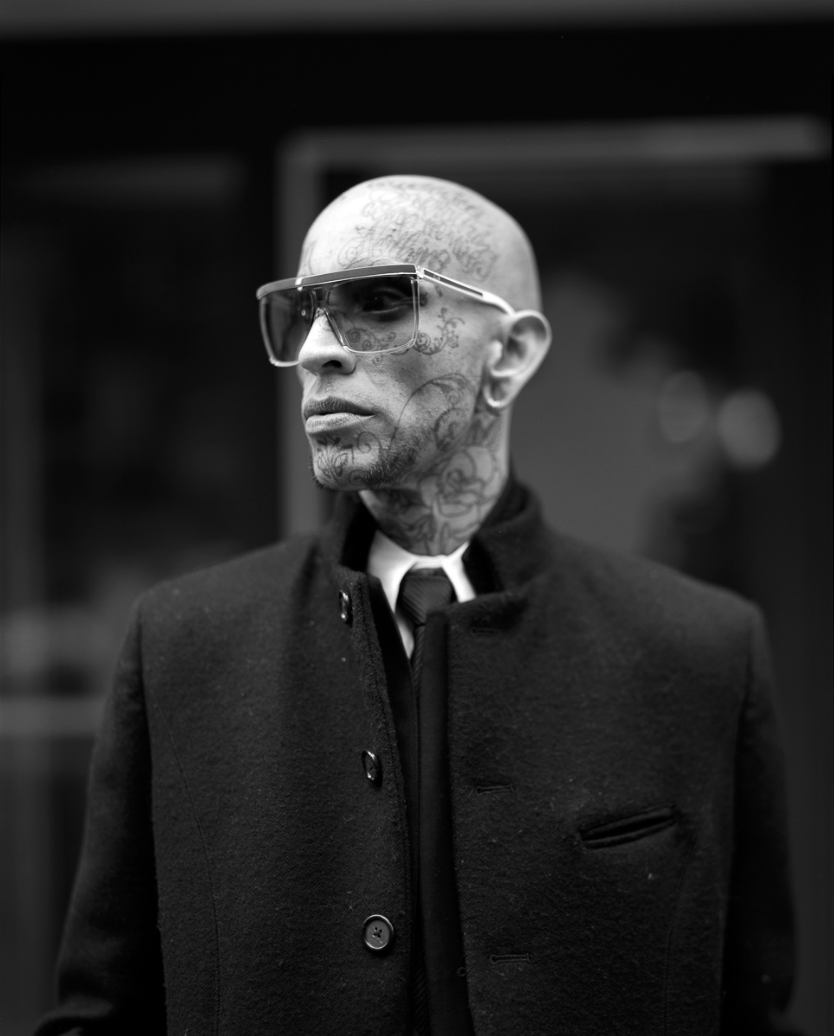

Craig, 2006- Fall River Boys

JTD: Conversely, your work crosses boundaries of sexuality, race, class, gender, location, lifestyle, etc… and in previous conversations, you’ve mentioned it is important to work across these boundaries. Can you elaborate on why this is important to you as a photographer and how it plays out in your work?

RR: Much of the work I made between Pier 45 and Touching Strangers was about crossing those boundaries. I was traveling and exploring America and her psyche. I focused much of my work on places and communities that were often viewed as blighted or on a very different track than the top-tier American cities that were benefiting from the expanding real-estate bubble.

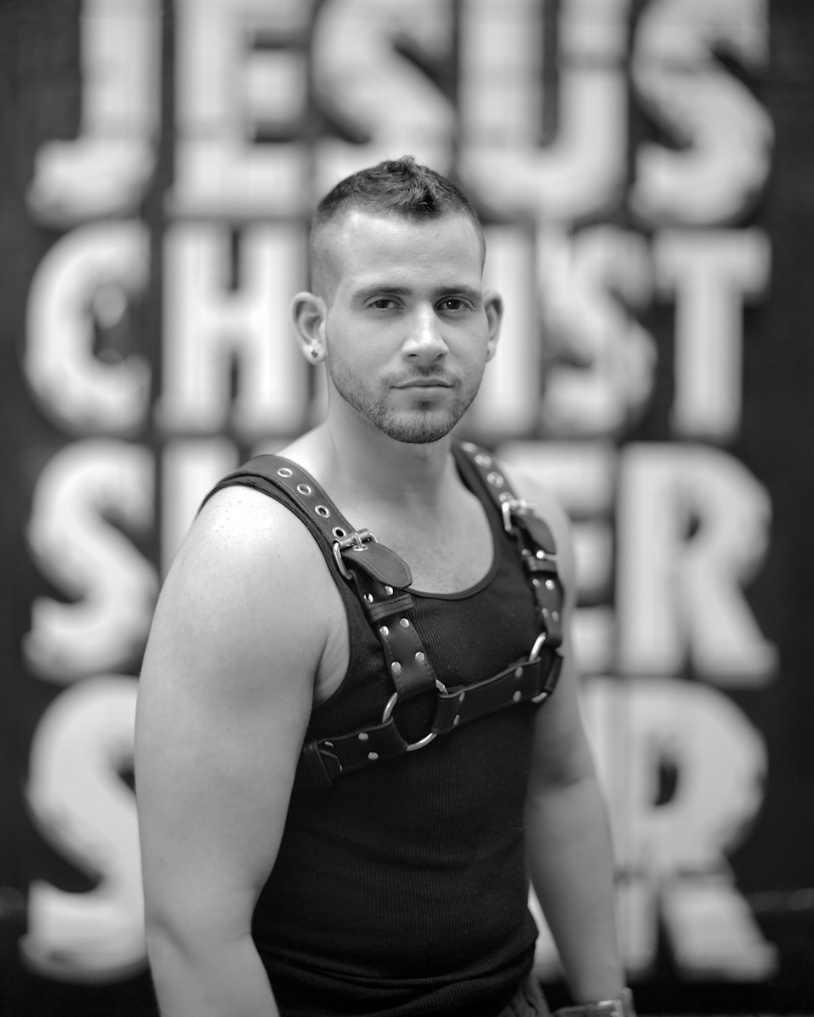

David; Okalhoma City, OK 2005 (Nokona, TX to Defiance, OH)- See America By Bus

See America by Bus was a culmination of my focus on the American “underclass” and it was there amongst the communal benches in those Greyhound stations were I first encountered the unusual circumstance of approaching two or more subjects, strangers to both myself and each other, and asking them to appear in a portrait together. That scenario led me into the Touching Strangers work. Now that I have some perspective on Touching Strangers I think that work merged my interest with crossing external boundaries of race, gender, and class, with something deeper and potentially meaningful in my own subconscious.

Shameerah, Gloria, and Rhonda; Amarillo, TX 2005 (Shameerah- San Bernardino, CA to Newark, NJ) (Gloria and Rhonda- North Las Vegas, NV to Tallulah, LA)- See America By Bus

JTD: Your photographs feel very hopeful and optimistic, yet also very authentic. I remember when I first met you, I was so relieved that you were such a nice, gentle person, because that is the sense I got through your work. I would have been so disappointed if this was not the case. Perhaps a better word than optimism is sincerity; your work feels very sincere, and many people are unable to be sincere in their work. How do you feel that this sincerity, or optimism, or whatever it is, is related to who you are as a person and the particular life you have lived?

RR: Thank you. I’m really happy that you get that feeling when looking at my work. I don’t know if it’s a question of authenticity or being comfortable in your own skin? I feel pretty good about myself and I am driven to share exciting things that I made with my friends and colleagues. I think a lot of art gets bogged down in academia and the conceptual and it forgets how to convey feelings and emotion. I even suspect that art, which elicits emotion, is regarded with some suspicion. In the end I think you just have to do what comes natural to you and not worry too much about where it falls.

JTD: You seem to be constantly photographing and always curious. Where do you find inspiration for making work? What’s next?

RR: I’m inspired by color, light, form, sex, food, culture, architecture, cities, music, nature, television, and film. It comes from a multitude of sources.

I’m almost exclusively focused on completing Manhattan Sunday and I am happy to report that it is on track to be released as a book by the Aperture Foundation in the fall of 2016.

All images © Richard Renaldi