Q&A: Regina deluise

By Rafael Soldi | Published on April 14, 2016

Regina DeLuise was born in Brooklyn, NY. She graduated from SUNY Purchase with a BFA and an MA from Rosary College, Graduate School of Fine Arts in Florence, Italy.

Regina is represented by Benrubi Gallery in NY and has exhibited her work internationally. She received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1993 and has traveled throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan and Europe. Her work is represented in private and public collections including The Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum in NY, Brooklyn Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Smithsonian Museum of American History, Houston Museum of Fine Art, and the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal.

Regina is the Chair of the Photography department at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) and has previously taught at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, The Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC and the University of Georgia, Studies Abroad in Cortona, Italy.

Rafael Soldi: We met at MICA, when you were my teacher. I know I speak for a lot of people when I say that you are an excellent mentor and you've inspired many of us in a deeply meaningful way. What role has teaching played in your life and practice?

Regina DeLuise: Thank you for saying that Raf. Teaching is very important to me. You and many others have enriched my life and practice beyond measure. At best, teaching is a dialogue, a constant inquiry illuminating an ongoing conversation for all involved. I started teaching at the invitation of Robert Kozma at Pratt. Teaching wasn't something I intended to do. My goal in going to grad school was to buy time, to get my practice back to the center of my life, not to get a degree and teach.

But, I very happily found myself in the classroom. The first revelation was that I had something to impart. I had been working on my own for about 6 years and I didn't have an immediate sense of that. Teaching gives me the opportunity to look critically at my own practice and voice what is important to me as well as consider what might be universally important. Young artists follow their inclinations, influences and interests. The art school experience puts pressure on those instincts; forces you to be articulate, not only in your picture making, but in the personal choices you make about moving into your life. Teaching gives me a front row seat in understanding how one establishes and sustains a life in art.

RS: You see so many students enter the art world as young artists, and the landscape is changing so quickly. What was it like to be a young artist in New York in the 1980's and how did the AIDS crisis color your experience?

RD: Big question. My teachers traveled to teach at Purchase from NYC. They were represented at galleries there and created a link to the city for me. Jed Devine—teacher then and lifelong friend, influenced more artists than he’d care to discuss—was represented by Daniel Wolf Gallery and recommended me for a once-a-week gig when I was a Junior. I traveled to the city and worked on Saturdays for a period. Upon graduation, they asked me to interview for a job opening. I was working there two weeks after I graduated and stayed for two years.

There weren't many photography galleries at the time, Light, Witkin, and Daniel Wolf Gallery were among them. In the early 80’s Daniel Wolf, collector and gallerist, was creating the photography market that exists today. He was hugely influential. It was a beautiful gallery on 57th Street that exhibited a large range of work. Extraordinary 19th century, mammoth plate photography by Gustave LeGrey, Carleton Watkins, & Eadweard Muybridge, work by Helen Levitt and Eliot Porter. Joel Sternfeld first exhibited American Prospect there. Daniel represented John Coplans, Jed Devine and Todd Papageorge. It was an exhilerating place to be right out of undergrad and was a continuation of my education and then some. Lee Friendlander, Gary Winogrand and Paul McDonough would come into the gallery after shooting in Central Park. Daniel was working with so many interesting and engaged collectors and curators of the day. Weston Naef, Sam Wagstaff, Maria Morris Hambourg, John Waddell, Susan Kismaric, Harry Lunn, etc. Although his gallery closed in 1985, he is a legendary collector, engaged in notable projects independently and with his wife, artist and architect Maya Lin. It was extraordinary to be a part of such an influential gallery. One interesting bit—we reviewed work of photographers on a weekly basis. Such access! I learned MoMA did the same thing and dropped off my portfolio the summer after I graduated. John Szarkowski bought two of my photographs which was obviously thrilling. This gave me some confidence and made future rejection much more palatable. I had a very fortunate start.

Jan Groover, another important teacher and friend was among the first photographers to cross over into the 'art' market. Her color still lives were making an impact. She was printing in an edition of 3 and destroying her negative. Jan’s work sold for $3,000, at that time, which was more in scale with painting than photography. She was represented by Sonnabend and Blum Helman, art galleries, not photography galleries. I'm getting a bit mired in particulars here, but, this is all to say what was happening around me and how things were different.

We did what you're doing now though, meeting other artists, going to openings, exhibiting and expanding our own experience. There was a different kind of access for sure, but there was no internet. I see what you can create through this medium as comparable. Perhaps in comparison, my experience was somewhat provincial. It was a very incredible time in my life. NYC was much rougher and real then I think it is now. It continues to be an enormously important place for a young artist to be... until it's not. And that's totally individual.

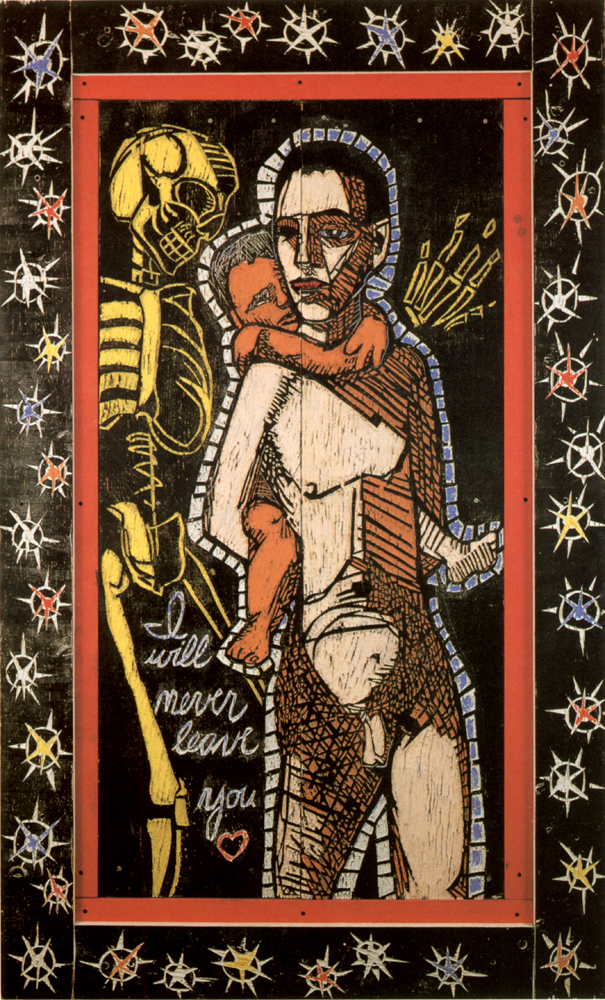

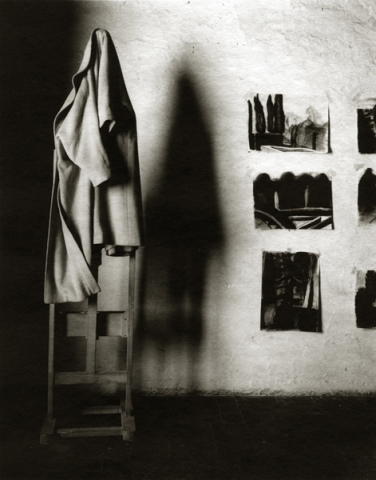

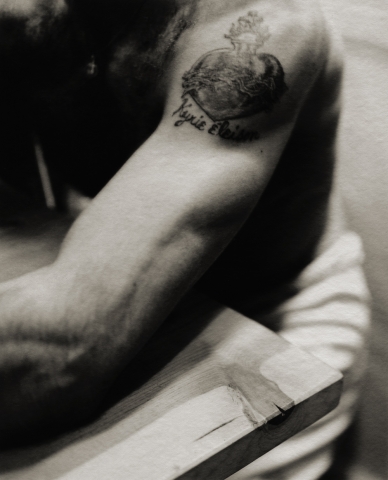

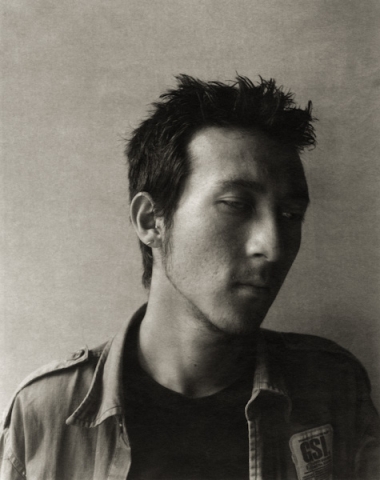

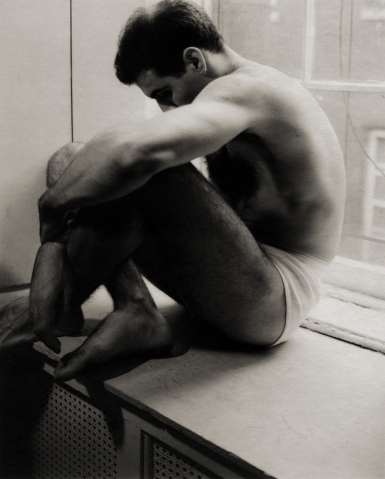

© Regina DeLuise, Adrian with Promise

I went to the city after undergrad with many of my peers and joined close friends who had left college earlier, Adrian Kellard among them. He and I shared an apartment on the Upper East Side. I worked at Daniel Wolf Gallery and he worked at Broome Street Bar. He used our apartment as his studio. He’d carry large planks of pine back from the lumber yard on the East Side in the 90's to our 5-story walk up. Adrian carved, painted and assembled his work there. He was a prolific and ambitious artist. It wasn't that unusual to come home to find him in discussion with some pretty interesting people—Holly Solomon, Lucas Samaras, Fr. Terrence Dempsey or Henry Geldzahler for example. Ultimately, he was represented by Susan Schreiber Gallery in Soho and was reviewed and written about quite frequently. We were making our way, which meant figuring out how to continue to make work, show our work and have a job. That hasn't changed. (We weren't asked to intern and work for free. I can't get my head around this.) Some of my friends did commercial work and created successful studios, but I felt clear about not wanting to make a living in that way. I continued to gravitate towards gallery and cooperative galleries before I came to teaching.

The AIDS crisis was real and terrifying. I don't want to speak in broad terms about this, but will say that Adrian contracted AIDS in the 80’s. He was considered a long time survivor at that time, living with AIDS for 5 years. I was there with him throughout. He was on the front line of all aspects of the disease. The personal, the political and existential. He never stopped making work. Adrian was in and out of one support group after another as all the other participants would die. He had a doctor who died before he did. Like so many others, Adrian went through so much and so bravely. His work, which centered on his sexuality and relationship to Catholicism, was bold and impactful—it went from very angry to exquisitely poignant. Adrian was a beautiful man and extraordinary artist.

A year or so after his death in 1991, I left NY and lived in Vermont for 5 years. I became the executor of his estate and in recent years have placed it in collections across the U.S. The most comprehensive exhibition; Adrian Kellard: The Learned Art of Compassion was exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Religious Art in St. Louis in 2011.

© Adrian Lee Kellard, Promise, 1989 / 75 " x 45 1/2"

My NY was much more gritty—Ed Koch was mayor, Reagan era in full tilt—the city was rife with activism. ACT-UP was everywhere. I was part of WAC, Women's Action Coalition (WAC is WATCHING) modeled after ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and the Women's Health Action Coalition. Women artists, organized around the outrageous Clarence Thomas, Anita Hill hearings and a rape on St. John's campus. Paula Cooper Gallery became the place to plan ways to move from frustration into action related to women's rights. We had a DRUM CORP! One of the most compelling actions I took part in was right before Mother's Day at Grand Central Station. We produced a Mother’s Day card with a rose on the front that contained statistics of how much money was owed to women in child support. Our card listed legal and health resources for underserved women. During morning rush hour, a huge pink banner reading, IT’S MOTHER’S DAY: $30 Billion OWED TO WOMEN IN CHILD SUPPORT was carried out in front of the information train board and unfurled by two women as the drum corp pounded. We quickly handed out hundreds of our ‘Mother’s day’ cards. As you can imagine, the drums in the concourse of Grand Central Station were thunderous. The banner, and this number in billions made for a powerful action.

NYC may not be gritty, and may or may not be the site for actions today, but your generation continues on and is deeply committed to effecting issues of inequality. I see tremendous bravery all around me. I see apathy too, which I don’t understand. I didn’t understand apathy in 1992 either though. The stakes are still so high.

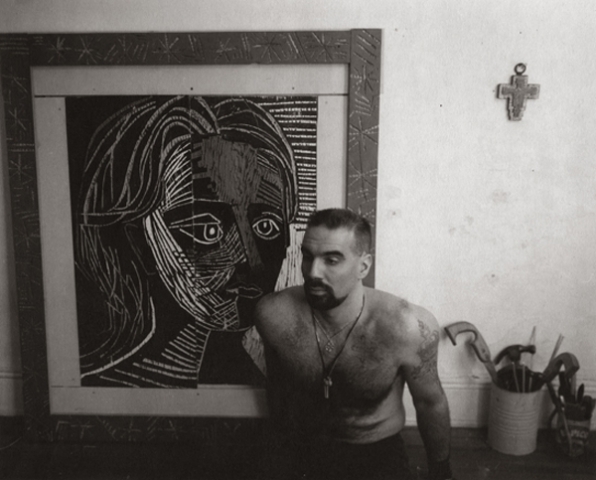

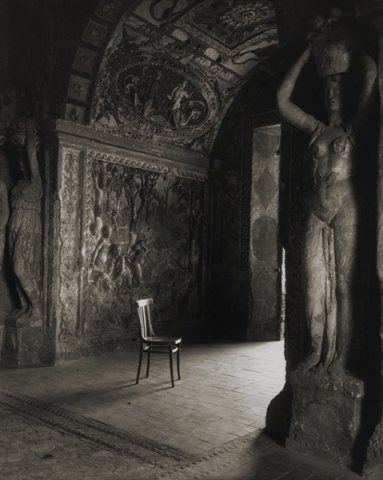

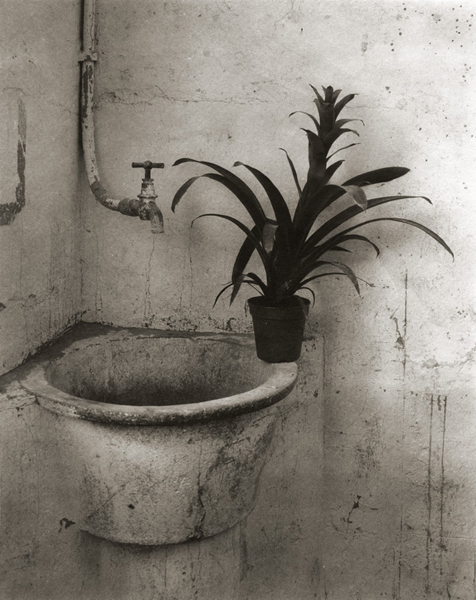

©Regina DeLuise, Adrian's Studio

RS: You mentioned to me that travel speaks to your mindset, though not necessarily to your work. Can you elaborate on that?

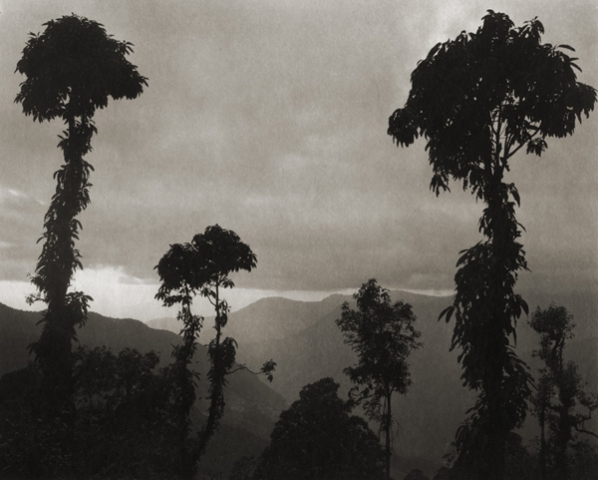

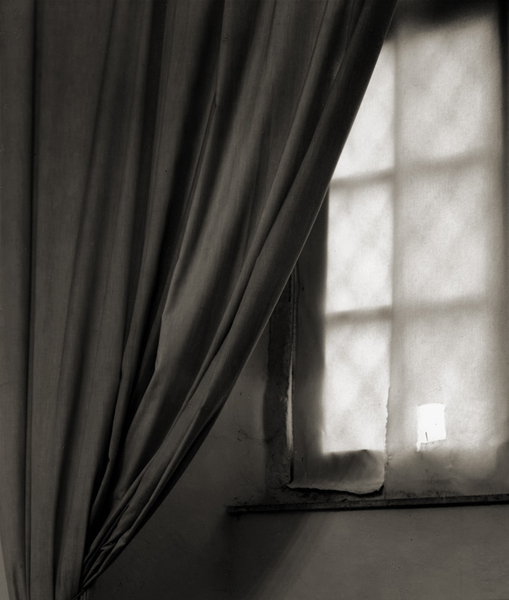

RD: When I say travel is more about mindset than place, I'm referring to my desire to keep something of a shaky ground under my feet when working. When I travel, I don't know what I'll find. I'm really drawn to the not knowing, the air feeling different, having the challenge of communication, a surprising quality of light. These kinds of things... The greatest benefit as well as the greatest challenge of being an artist is working with what is yet to be discovered. You have to trust yourself when you're out in the world, you have to trust others too. Learning to find one's balance on the moving platform of a creative life keeps me agile. Travel is one way I experience this. The blank space of a studio—or time alone to work can function in the same way.

©Regina DeLuise, Jungle Trees

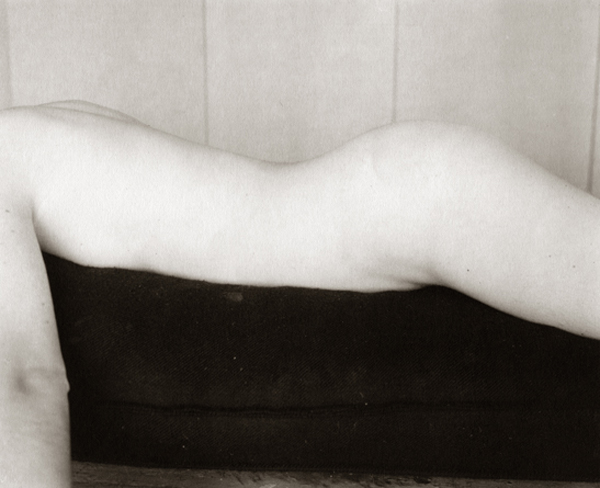

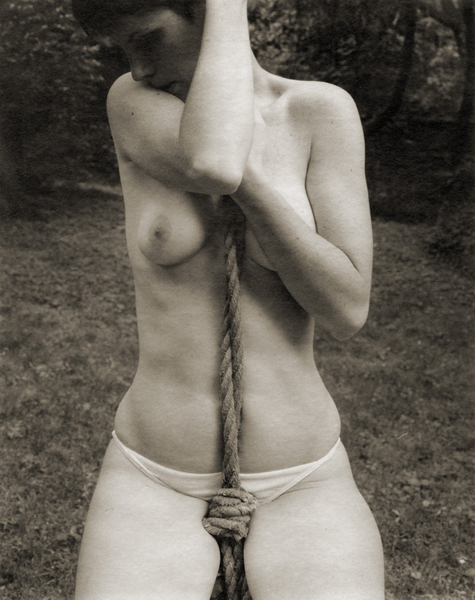

RS: The figure has a strong presence in your work, not necessarily because there is a lot of it but because your portraits have a transcendental quality. You handle the figure in a quiet and meditative way, which perhaps speaks to your process but also to your nature. You've photographed people who are close to you over time, but other subjects are strangers or acquaintances. Somehow, regardless of how well you know the subject, there is an intimacy that prevails throughout. What attracts you to the figure, and how do you bring about this intimacy when a subject is not close to you?

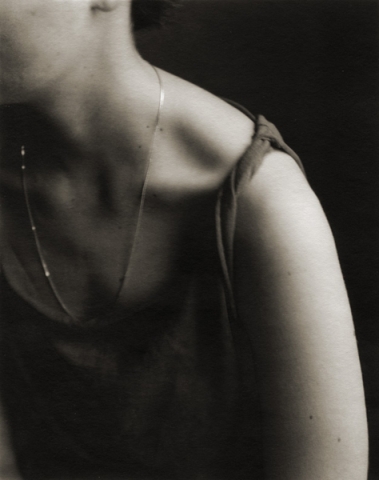

RD: The body was my first subject. It remains a constant, always compelling to me. The sensual, visceral, tactile nature of the world has always been my ground. When handled skillfully, how our natural surroundings have impact, how my interpretations can change a viewer's mind is a mystery. It’s about imposing myself and ideas on the world .. it’s about trying to define myself...I choose to do this in relation to the natural world. Why does a ‘simple’ Sugimoto seascape blow my mind? It’s endlessly fascinating to discuss (why I love teaching) but at the end of the day, it's about commitment. My love of the large format camera and palladium printing are explained here too. I can handle and manipulate my materials, feel the paper, mix my emulsions, experience the heat of the sun if I’m printing outside. It’s about the sensual aspects of life, the physical body, emotion, experience. It’s not cerebral for me.

© Regina DeLuise, Nude Leaning Forward

RS: Let's talk a little bit about process. For the majority of your career you've worked with an 8x10" camera and the platinum-palladium printing process. Let's talk first about your image-making process, there is a mystery and poetry in the act of veiling yourself behind the camera, both psychologically and physically, since you are, in fact, hiding under a cloak. It seems so counterintuitive to procure blindness to make an image, which is so much about seeing.

RD: The action of working with this camera is it's own kind of poetry. It stops time. I'm not talking about the shutter and aperture thing. I’m talking about the expectation of how to photograph, how to find your subject. It takes a long time. If it’s a portrait, that time allows the sitter to drop artifice and self consciousness. They watch me dance around, manage this big camera, pick up and move it here and then there, and back again. I'm talking to them, directing them from under the dark cloth. The artist becomes disembodied. The sitter can have their own experience, imagine what I might be seeing, being observed becomes more abstract. They project themselves (essence) if they intended to or not. In the best of my portraits, the ones you find transcendent, that must be part of the power of the image. It's certainly a kind of collaboration. The 8x10 keeps the mystery in the action of making pictures. It’s incredibly physical. And yes! This camera does protect the photographer, allows so beautifully for unanimity. Do you agree? My camera is my veil. It really feels like I’m doing a disappearing act and making space for a kind of alchemy.

RS: I definitely agree! I would think almost every photographer finds comfort behind the camera, for obvious reasons—and it's a slightly different experience for each. I know Avedon liked shooting from the hip so his sitters would look at him and not the camera. I'm in your camp, for me the world looks different through the camera and something very magical happens when it veils my normal way of seeing.

I've been thinking a lot about making work in a long-term context. I think when we are young it's harder to make sense of the work we make, and there is often more pressure to explain ourselves. Artists with long careers have a context in which to nestle their new work, and a larger base from which to expand. With a long and prolific career like yours, what are some of the surprises, beauties, and challenges of making new work whilst looking back at your oeuvre? Does it get easier over time, or do the same challenges prevail?

RD: This is a good question Raf, one that’s been interesting to consider. I wish I could say it gets easier. Sometimes I think it’s like trading one kind of insecurity for another. In the beginning, making pictures was uncomplicated for me. There was a kind of naivete at work for sure. As time goes on and you have a greater context, you have more complex questions to consider. If I feel relevant in my own set of questions, I’m good. If not, terror can still strike. But this is important. This is the whole question of finding one’s balance on an ever changing platform, remaining agile. Being an artist is not for the meek of heart.

This said, it is incredibly satisfying to look at all the years of work. And I will take your expression of nestling new work into that oeuvre! I like that. There certainly is a broad base on which to stand now and wonders keep showing up. Nietzsche’s quote ‘a long obedience in the same direction’ speaks volumes to me. That’s what it is, continually moving forward in the same direction, being tenacious about the whole endeavor. Life has it’s twist and turns, but picture making has remained at the center of mine. I see my life in my work. I see my life in relationship to the world in my work. It is stunning to see what I let myself imagine my life to be, become just that.

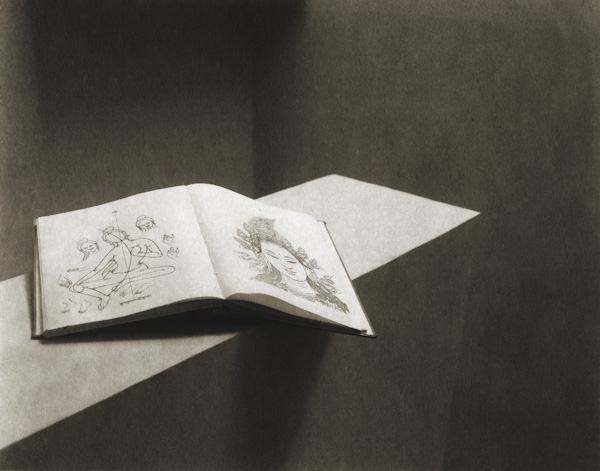

© Regina DeLuise, Bird Book

RS: What's next for you?

RD: I’ve been the Chair of Photography at MICA for 4 years now. It’s been incredible to have the opportunity to impact the growth of our department. You and I had a conversation as I began my tenure. Do you remember? You said, 'MICA Photo has all the ingredients to be great.' I took that to heart and worked very hard to bring all that energy together... to shine a light on the incredible artists that have come out of our program, optimize the experiences and avenues of success for our current students, and connect MICA Photo to the contemporary moment in our medium. I hope I’ve been successful in this endeavor. What’s next for me is taking it back to my own work. I’ll be doing a residency at VCCA (Virginia Center for the Creative Arts) this summer as well as traveling abroad for a month. I'll move from Chair back to faculty in the fall and am really happy about being in the classroom, more connected to the students and their process. I’m planning my 2017 sabbatical too, so what’s next is a renewed focus on my work.

RS: I do remember that conversation and it does not feel like it was 4 years ago! I've been blow away by the energy that you and the new faculty have brought into that department and it shows in the work being produced by the current students and recent grads, which is the ultimate test! I'm looking forward to seeing all the exciting things to come in your practice.

All images © Regina DeLuise