Q&A: patricia lay-dorsey

By Jess T. Dugan | February 18, 2016

Born in Washington, DC in 1942, Patricia Lay-Dorsey brings her training as a social worker (MSW, Smith College for Social Work, 1966) and over three decades as a visual artist to her work as a photographer. Her work has been exhibited internationally and has been featured in the New York Times Lens Blog, the Huffington Post, Feature Shoot, BBC World Update, and many additional venues. In 2013, her self-portrait project about living with a disability, Falling Into Place, was published as a book by Ffotogallery in Cardiff, Wales, and has received critical acclaim.

Jess T. Dugan: I'm intrigued that you became serious about photography relatively later in life. What motivated you to start making photographs and what was the impetus for this shift in your creative expression?

Patricia Lay-Dorsey: My interest in photography was a direct outgrowth of my keeping a daily blog for six years with written entries illustrated by point-and-shoot photos. By July 2006 I was tired of words and just wanted to take pictures, so I decided to get serious about photography, bought a Canon DSLR, took some photography classes, and never looked back.

I soon found that photography satisfied the need I have to connect with people, a need that had led to my getting a Masters in Social Work in 1966. It also allowed me to continue exploring my fascination with visual art that had blossomed when I’d returned to school to study fine arts in the 1970s, and had launched my career as an exhibiting and performance artist in the Detroit art world of the 1980s. And there was one more aspect of my character that photography allowed me to express, and that was my long-time commitment to global peace, social change and our common humanity.

I hoped that as a humanist photographer I could use my camera to break through the superficial views we sometimes hold of one another, views that can lead to misunderstandings and stereotypes. If I dared to share my own and my subjects’ stories with an intimate honesty, could it not counter prejudices that paint persons of a different age, race, ability, sexual orientation, religion, national origin and class as “other?” Was it not possible to use photography as a tool for social change? Was I naïve to believe that our common humanity would win out in the end? I chose to let my camera answer an emphatic “Yes!” to all these questions.

From Falling Into Place

JTD: The first project of yours that I saw- and was completely captivated by- was Falling Into Place, your series of self-portraits depicting your daily experience of living with Multiple Sclerosis. You have written about your desire to make work about disability from an insider point of view, and also about the challenges you faced regarding your own perception of yourself while making this work. Could you expand on that and tell me about the process of making this series? This project was recently published as a monograph and has also received a great deal of press over the past few years. What is it like to experience your photographs, which are intimate and highly personal, as they become public? How did your relationship with the work change?

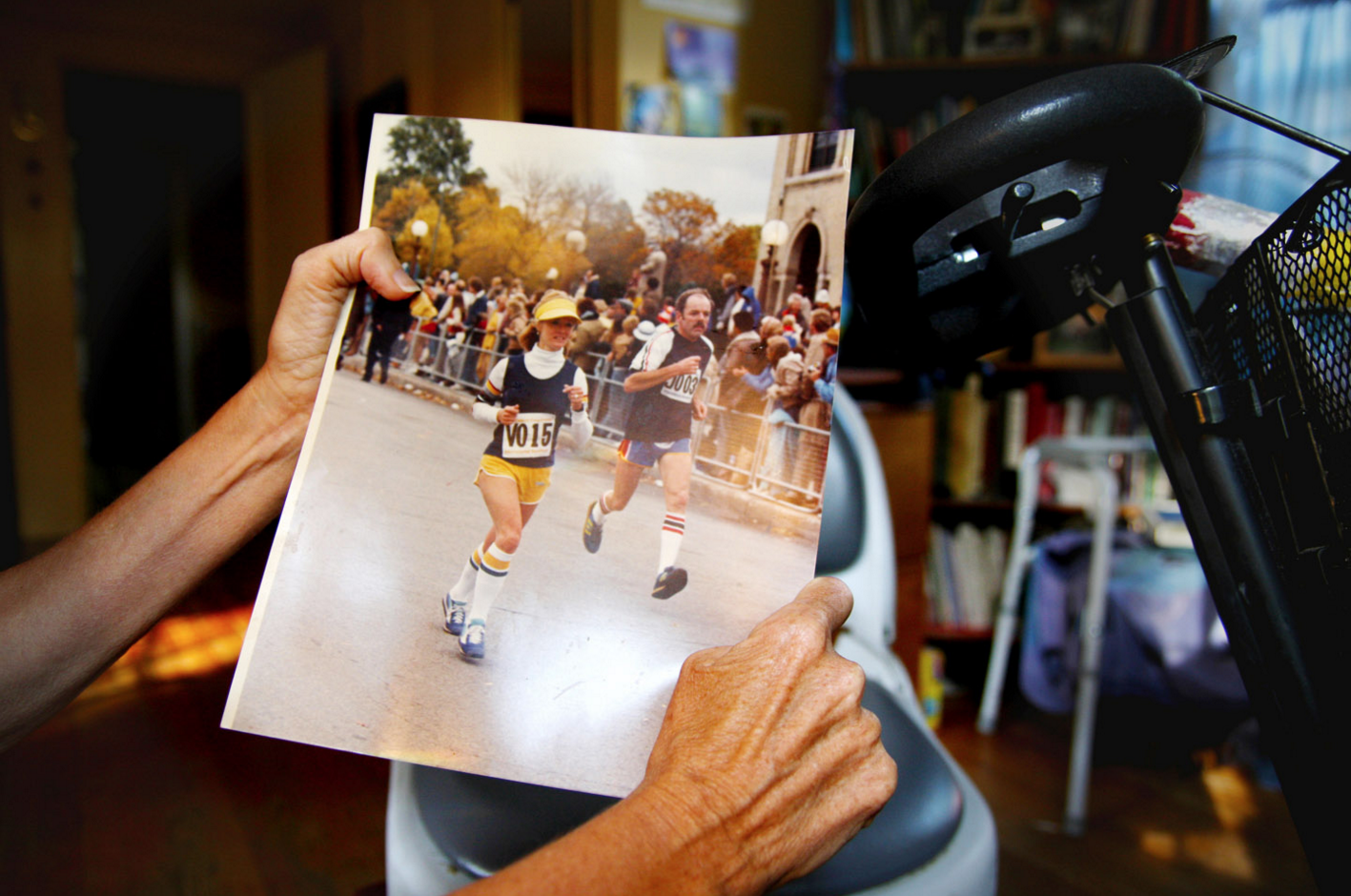

PLD: It was my need to tell the story from the inside that led me in June 2008 to start taking self-portraits of my day-to-day life with a disability. I had been diagnosed with chronic progressive multiple sclerosis 20 years earlier and was finally ready to confront my own feelings and experiences as honestly and forthrightly as possible. What I had thought would be most difficult, i.e., the physical act of taking the photos, proved to be the easiest part of it all. What was hard was looking at the photographs afterwards. I had never liked letting people see my personal struggles, like getting out of bed, getting dressed, and taking the falls that inspired me to call the project, Falling Into Place. So why was I now opening the door to sharing these most intimate moments with the world? I can’t really say.

From Falling Into Place

What I did begin to know firsthand was how it must have felt for the subjects of my earlier documentary projects to expose their lives through my lens, and I didn't like it. It wasn't that I minded other people seeing these intimate glimpses into my life; it was that I did not want to look at them myself. But I forced myself to take a good hard look at every detail the camera caught and in so doing, I began to accept my disability in ways I never had before. As a photographer, I began to see the outward appearance of how the MS affected my life as interesting rather than negative. And I finally recognized how hard my body works to do everything I ask of it. Feelings of gratitude replaced the feelings of shame that my defense mechanisms had partially covered up for years. I came face-to-face with myself.

This internal transformation has allowed me to use the photos, book and video of Falling Into Place as a springboard for discussions about disability, self-image and creativity using slide presentations, lectures, gallery events, interactive dialogues and classes with high school and university students, disability organizations, and the non-disabled and disabled members of several communities. Falling Into Place not only gave me the tool I needed to integrate my own personal journey, but to help others – both disabled and non-disabled – integrate theirs as well.

From Falling Into Place

JTD: I want to ask you about the notion of bravery. I imagine people often tell you that you are brave for making the work that you do. This is something I am also told about my work, and I don't always know what to make of it. On some level, we are dealt a certain hand, and all we can do is choose to embrace who we are and the life that we live- or not. To me, this choice is where the bravery lies. What are your thoughts about this idea in relation to your own life and work?

PLD: To be honest, the word “bravery” in relation to me and my work makes me uncomfortable. In fact, it was non-disabled journalists’ and photographers’ habit of describing the disabled subjects of their articles and photo projects as leading brave and/or tragic lives that compelled me to undertake my self-portrait project, Falling Into Place, in the first place. I was determined to tell the story of a disabled person’s day-to-day life from the inside so people could see that we are neither brave nor pitiful, but simply living the lives we have been given with as much grace and dignity as we can muster. We are human beings just like everyone else. If I am brave, so are you, and so is everyone else. We all have obstacles to overcome.

To me, bravery is much more than simply dealing with our challenges, be they physical, emotional, situational, economic or relational. True bravery means going beyond what you and others see as reasonable or even possible. Someone like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was brave when he met violent hatred with love and non-violent resistance. My 76 year-old friend, Sister Julia Slowik, is brave when- after having been sent home to Michigan to undergo surgery and months of chemotherapy for cancer- she returned as quickly as her doctors allowed to continue companioning the people of her parish in the extremely dangerous city of Juarez, Mexico. When I look at the lives of Dr. King and Sr. Julia, taking and sharing photos of my daily life with a disability hardly qualifies as “bravery.”

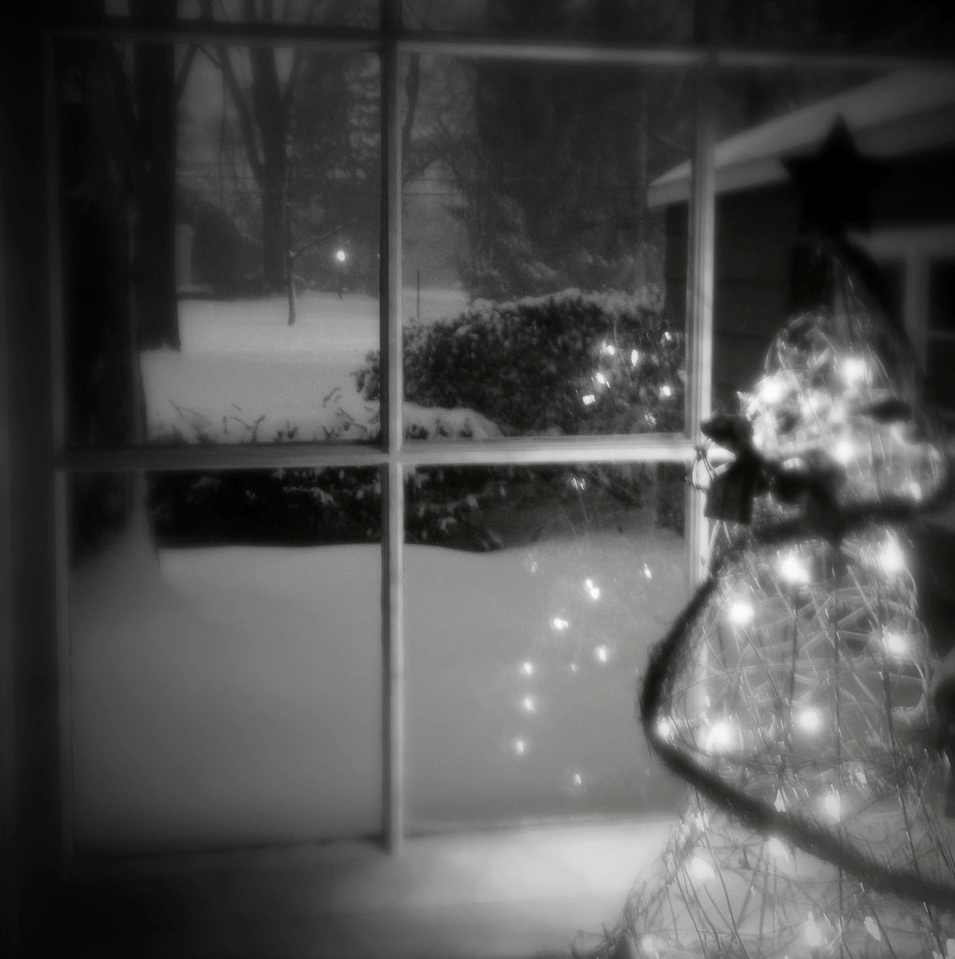

From Falling Into Place

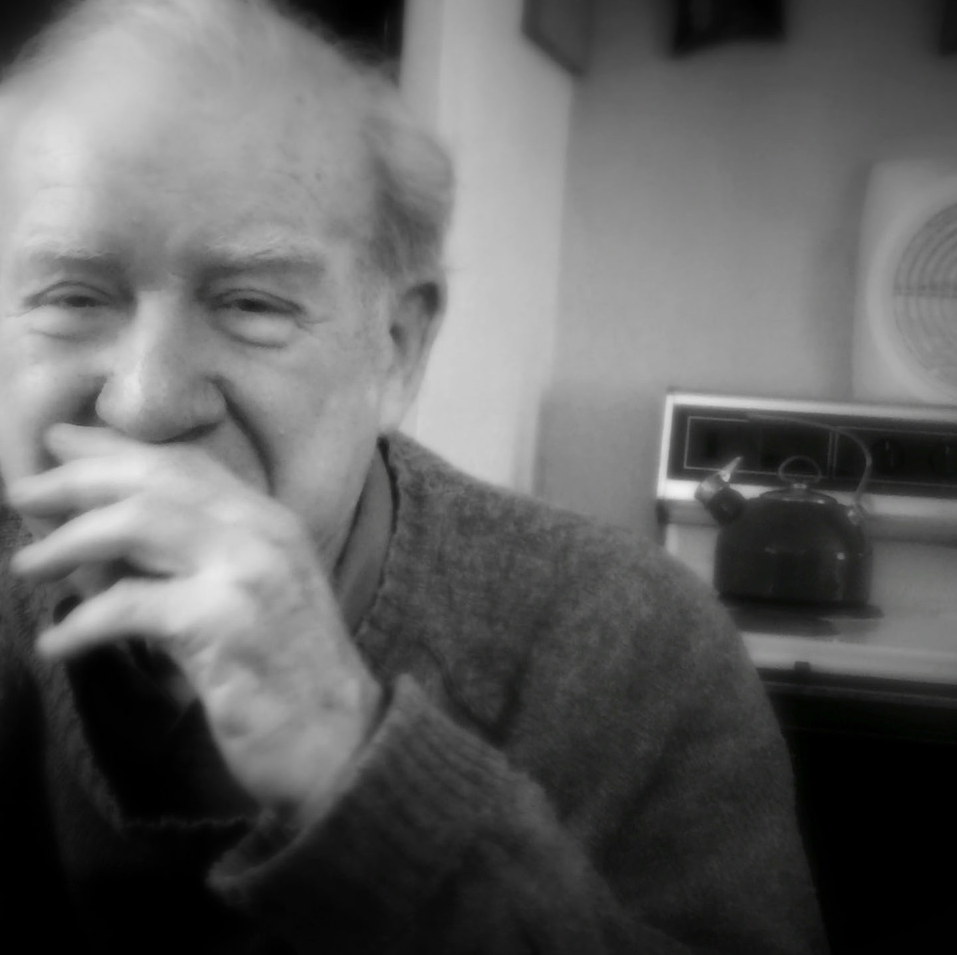

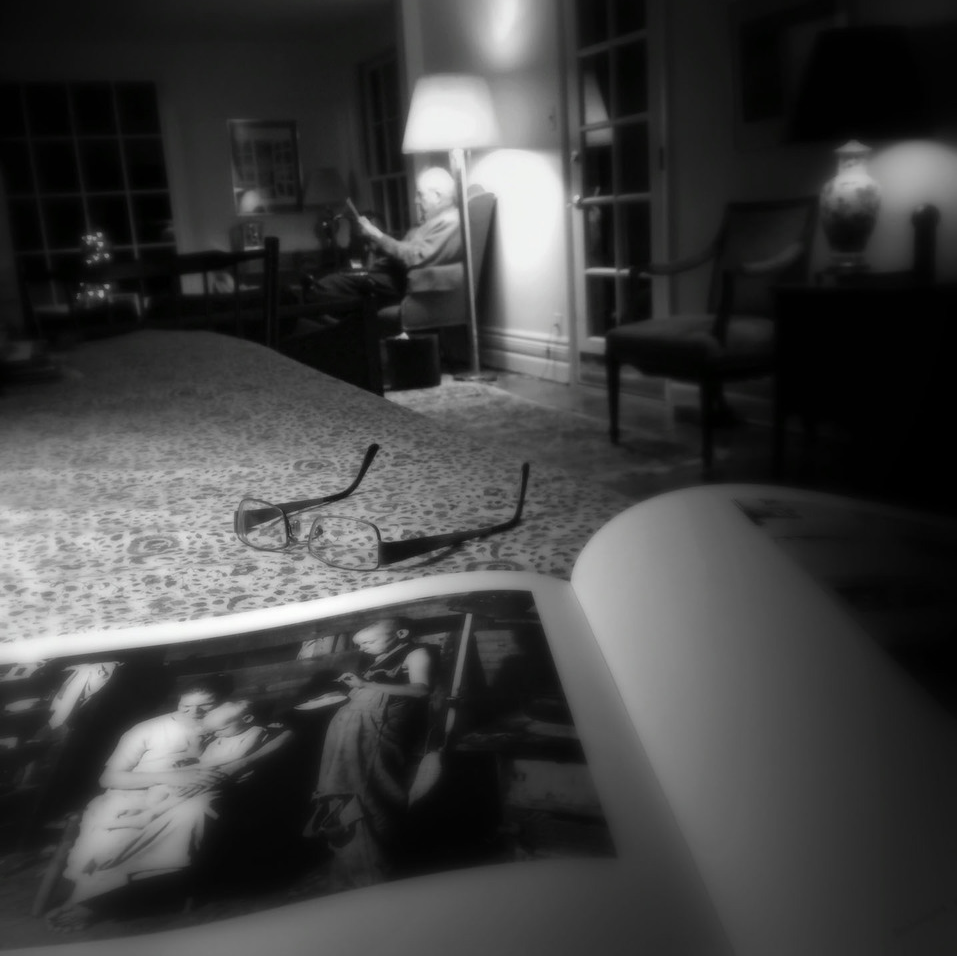

JTD: Tell me about your project Tea for Two, soft focus black and white photographs of your husband Eddie and your life together at home. I was moved to read that the title of the series comes from a song that Eddie has played on the piano and the two of you have sung together every night for the past 50 years. There is a particular kind of intimacy that comes with the passage of time. Having only been in my relationship for three years, I can hardly imagine what that intimacy must feel like over a lifetime. How did this project begin? What have you discovered through the process of making it?

PLD: The project Tea For Two started on January 28, 2015 with one blurry b/w iPhone pic that I took and posted on my Instagram feed @patricialaydorsey. The caption was, “I am trying to break my addiction to sharp focus." Within months I had taken and posted on Instagram hundreds of b/w soft-focus iPhone photos of my day-to-day life.

From Tea For Two

What started as an artistic and technical challenge soon became a new way of seeing. And the lens I used had nothing to do with aperture or ISO and everything to do with the life energies that surrounded me. I began to see that everything is in motion and sharp focus tried to freeze life and present it as static. With this new awareness, my old photos looked stiff and unnatural while my use of blur imparted a liveliness that felt real.

During the winter of 2015 we experienced the third coldest February in Detroit’s history. The snows that would not melt made it tough for me to get out and about using the devices I needed for my disability. My husband Eddie and our life together at home became my primary photographic subject. Not just what I saw but what I felt. I posted on Instagram every iPhone picture I took of Eddie and me, and shared stories from our many years together in my captions. The response from my IG followers was phenomenal! They saw something special and encouraged me to take this project seriously. In April, the remarkably positive responses to this project that I received at the New York Times Portfolio Review in NYC and Photolucida in Portland, OR, made it clear that my Instagram followers had been right. Several of the reviewers and photographers even wept as they looked through my prints.

From Tea For Two

There was obviously something about this intimate yet ordinary view of a long-term marriage that touched people deeply. But most importantly, focusing so much of my creative time and attention on this dear man and our life together deepened our relationship in unexpected ways. Not only did it show Eddie how important he is to me, but it helped me recognize and appreciate the unique bond that we share. Tea For Two made our marriage stronger than ever.

From Tea For Two

JTD: Your work is infused with radiance, warmth, and a passion for life and for others. To what extent do you think that your photography is influenced by your background in social work and your work experience over the past few decades? And where do you find inspiration?

PLD: I’d have to say that I find inspiration in what I see, hear, read, think and feel as I go about my day-to-day life. That’s why Instagram suits me to a T. Every morning I wake up not knowing what pictures I’ll take that day, what stories I will tell in my captions, and what dialogue they might foster between me and my followers or even better, between those who post comments to each other on my feed.

For instance, a few days ago there was an heart-wrenching dialogue between two residents of Flint, Michigan in which they shared through their comments back-and-forth to one another on my IG feed, exactly how they and their families are dealing with the horrendous man-made water crisis that is poisoning the children of their city. I have been staying fully informed on this situation and have been regularly posting photos – my own and others - accompanied by lengthy captions trying to put the situation in perspective. I have found that Instagram gives me the opportunity to use photography to draw attention to situations like this in ways that break down geographical barriers and help us see that we are members of one global family who care deeply about each other. I call it “creative activism.”

JTD: You seem to be getting busier with each passing year. What is on the horizon for you as an artist?

PLD: Yes, I am wonderfully busy these days doing interviews for online magazines and websites, preparing for solo exhibits in 2016 at Davis Orton Gallery in NY and Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, OR, looking forward to being a presenter this June at Bill Schwab’s Photostock 2016, and anticipating living in community on Captiva Island, FL for 4 weeks in 2017 with 8-9 multidisciplinary global artists during the Rauschenberg Residency that I was recently awarded by Critical Mass 2015.

Less and less do I feel it necessary to run around making things happen professionally because, in this close-knit world of photography, one opportunity seems to lead to another. The people in this global community are so generous-spirited and open to new ways of seeing that all we photographers must do is keep following our passion – which is taking photographs - sharing our work publicly, and trusting that our “babies” will find their own way if we let them. And most importantly, remaining grateful…

All images © Patricia Lay-Dorsey