Q&A: Odette England

By Hamidah Glasgow | December 16, 2021

Odette England (b. 1975) is an Australian/British artist, whose artwork has been exhibited widely across the US and internationally.

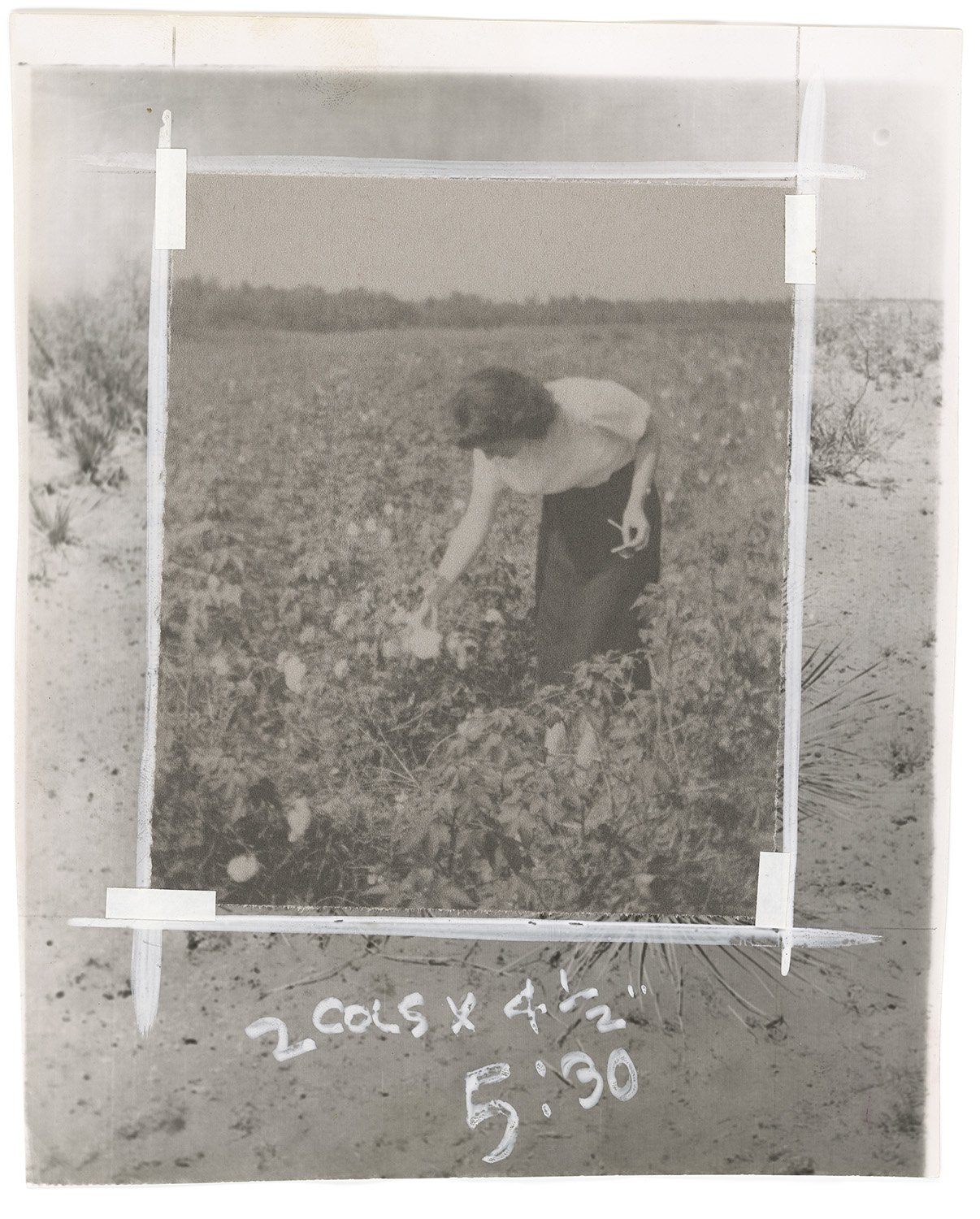

Odette England uses photography, performance, writing, and the archive to explore themes of autobiography, land, gender, and ritual. She often manipulates her negatives and prints, intervening with their surfaces. She uses expired film, broken cameras, and tainted chemistry. Since 2005 England has revisited and photographed the remnants of her former farming community. She walks the land with her parents who lost their livelihood to falling milk prices and a lack of government investment in agriculture. Many of the images England creates are unique, in keeping with the stories they reference.

HG: Odette, it has been such a joy working with you on the current exhibition through the Center for Fine Art Photography, Degrees. Your processes for creating work and your thought processes are unique. Tell me about the trajectory of the series as it stands now.

OE: Likewise, Hamidah, it’s a privilege to be partnering with you in a visual conversation about something all of us are responsible for: our earth, our home. This is the first body of work I’ve made where an extreme weather event – a series of mega-fires that became a national ecological catastrophe – unfolded around me as an artist. A little backstory: on December 20, 2019, now known as Black Christmas, more than 120 fires raged across southern Australia. The fire at Cudlee Creek, a small town in the Adelaide Hills, destroyed 500 homes and buildings, 5,000 livestock, and burned 25,000 hectares of land. I was visiting my folks at the time, who live about 20 miles from the fringes of the fire zone. I had intended to spend my two months in Australia photographing in our former farming community. The fires changed that. We instead traveled in and around Cudlee Creek making photographs and helping people and animals.

December 20 was especially windy and hot. It got to 48.1 degrees Celsius (about 118.5 Fahrenheit). I spent that day photographing the sky. It changed so rapidly, the fires created their own weather system, turning from blue to grey to mud red.

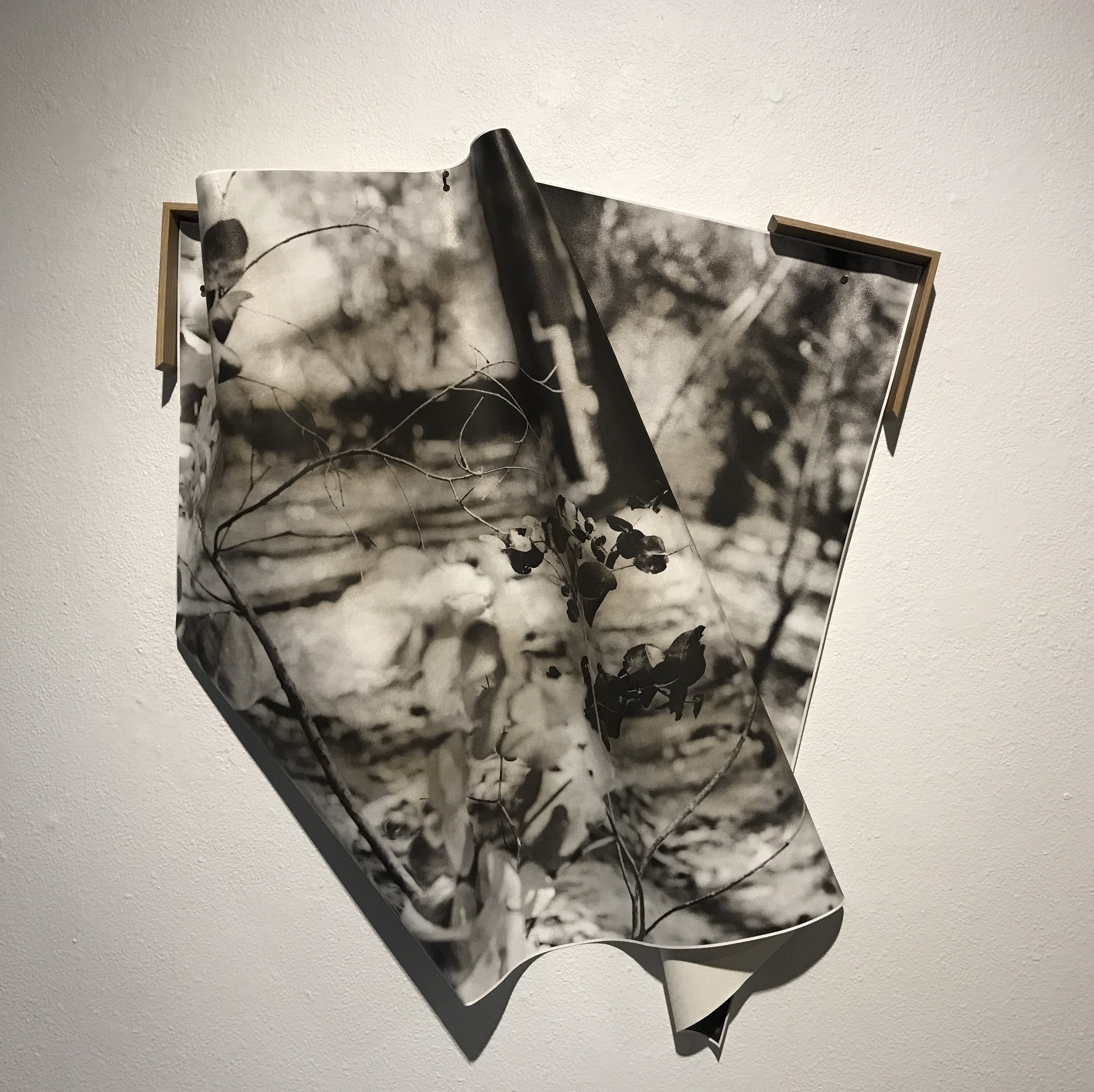

When I returned home to the US, I processed the films but was disappointed with the results. The images felt incompatible with what I’d seen. I made some test prints and hung them in the studio. I took them down after a few months. I felt disillusioned. There was no visceral quality. After a long period of looking, and then not looking (which is sometimes more important), I realized the photographs were failed substitutes for the reality of all the ash and smoke in the air. So, I rubbed ash into my darkroom prints, which I’d collected on a whim, not knowing how important it would become. I printed onto raw unfinished canvas, which I folded and crumpled to mimic flames, to honor the identity and shape of fire. I created my own ash-based paint and doused my prints. These generative, explorative acts of disrupting print norms and standards turned my works into surfaces for feelings. It took seventeen months to get to that.

I’ve since become fixated on the limitations of shapes and frames. Painting, photography, and printmaking still favor squares and rectangles, hung on walls. Fusing mediums for this work was also freeing. Even though I record information with my cameras, I almost always elaborate on it. I’m an elaborator, which is a medium and discipline all its own.

HG: You are very trusting of the people you work with and allow them to create their own spin on installation of your work. That trusting is so much a part of your collaborations with your family and it requires a great deal of non-attachment. How would you explain that to people?

OE: Thank you for choosing the word non-attachment, which is about being attentive and thoughtful, as opposed to indifference which relates to apathy or dispassion, even carelessness. I’m attached to people, working with them, contributing with them. People are infinitely interesting, precocious, and wild.

Growing up, we didn’t value ‘stuff’. We cherished stories, heath, humor, wisdom, and giving everything a go. My folks prioritized learning in-the-world through doing rather than having. We had few toys; instead, we were encouraged to make the most of a 200-acre ‘playground’ for our imagination. This upbringing is, I think, one the reasons I feel comfortable undertaking heinous acts with family snapshots, like cutting myself out of them. I’m not cutting my actual body, I’m cutting a flat representation to see how it feels as a gesture, as an act of permanency. It doesn’t cause me physical pain because I don’t associate the ‘thing’, the photograph, with my personhood. I do remember feeling naughty in cutting the first one, and then thinking, hmmm, let’s try it with negatives. And then maybe I’ll hole punch some, then bury some, then… Because once I do it, I can’t take it back. Irreversibility can be seriously sexy. How far is too far? I don’t know yet because I haven’t gone too far.

Trusting others in the artistic process seems underutilized and undervalued. Curators, exhibition managers, preparators, handlers, archivists, printers, framers, all can teach us something new, exhilarating, edifying about our work if we’re ready to let them in, to welcome input and pay attention to their insights. I’ll never have all the answers to my work, nor should I expect to. When I make something, it has its own personality and wishes. It commands its own space. It’s my job to be flexible and responsive to what the work has to say, to tune in, which means a lot of waiting. The ensuring conversation I have with my work can also make me feel exposed, that’s a very good thing. And when the work leaves me, it’s positioned, hung, lit, read, understood, discussed, critiqued, and dismantled in all sorts of ways I can’t predict. Trying to exert too much force or pressure on any of that feels disingenuous.

Non-attachment requires a different kind of faith. I never think my work should own me. I don’t need to fixate on every detail. Everything goes wrong, and breaks, at some point. My work constantly changes (as do I). Inviting others into the process feels authentic and kind. My work is richer for it. And I am, too.

HG: I’d like to hear about how writing fits into your day. Are you a person that writes every morning or someone that writes when inspiration hits? When did you first realize that you are a writer?

OE: My love of writing comes from a long history of participating in oral storytelling. Which is to say, first, listening. Storytelling was part of daily life at the farm. Every farmer I know loves to spin a yarn and most are very good at it. They tend to be economical with their words, they use few adjectives, even fewer metaphors. In hindsight, storytelling was one of the cheapest forms of entertainment available to us. It was about sharing, getting closer to people, and fostering community. Oh, and being comfortable with laughing at each other’s failures and silliness and mistakes in a loving way. In that respect, it was a valuable training ground for how to open yourself up to others, to be generous with your ears and your attention. We learned about life and each other’s strengths and weaknesses through the shortest and tallest of tales. In the absence of books, my younger brother and I made up stories about finding fairies or buried treasure or mythical places. I learned about friends and relatives who’d passed away, or lived far away. Dad is a fantastical storyteller and the older I get, the wilder the same stories I’ve heard since childhood get. Mom is the writer. She’d get out her old blue Remington typewriter and author letters to those too far away to call. She also crafted concise captions for the snapshots she’d take with her Kodak Instamatic, then cut and stick them into albums late at night.

Committing to words is a daily discipline. Sometimes they come hard and fast, my mind forms sentences quicker than I can get them out. That’s exciting. Or I’ll be in bed and a little idea pops into mind and I have to get up and note it down because in the morning it won’t be as good or as sharp. I don’t have a preferred time of day for writing and I don’t wait for a mood or feeling to strike. I feed my writing by reading every day, and by choosing an image to write about every day. Any image, usually not my own, ten minutes of freewriting. Sometimes I’ll write prose or a list of bullet points. I have lots of notebooks filled with ‘image observations’.

This summer I listened to the author Eileen Myles talk about writing. One of the many things they said that has stuck with me is that we have permission to be deviant in our writing. I love that sentiment: being eccentric and unexpected and unorthodox because we can. And, because it’s fun.

HG: I’d like to hear more about this statement from your website. “Many of the images England creates are unique, in keeping with the stories they reference. She mixes preciousness and the unrepeatable with low-fi processes.”

OE: Every story in the world is a one-off. Some seem similar (and familiar) but each is distinctive. Even hearing the same story is unique experience each time because where we are, how we’re feeling, what else is going on around us, inside us, influences us.

I trained as a painter so I’ve never felt pressured to make a photograph in one way or another. I read that the photographer Jan Groover felt similar, adding that she felt no need to make even a “good photograph”. I like thinking of a photograph as a single experience of thousands of micro decisions cropped from the expanse of the world. That single experience is my material starting point. It becomes my world of potential.

Photography is so much about precision, being or feeling in control of a device or situation. I like negating photography’s exactness, being rascally with my negatives or prints. I don’t white-glove my past and feel little need or obligation to treat my work like that. This isn’t to say that there isn’t care for what and how I make. My upbringing was hands-on, improvisational, making-do, seeing our bodies and touch in almost everything we did. Besides a painter and ceramicist, my paternal grandmother was an extraordinary baker and florist. Spending time with her and mom at county fairs was an excellent education on how care can reveal itself in hand-made objects, from pastries and clay pots to exquisite floral arrangements of roadside weeds.

When it comes to making, I run toward risk; the risk of slippage, things collapsing or malfunctioning or on their way to ruin. I’m certain it’s because that was my visual reality. Nothing was new or pristine. Sure, our clothes were washed and the dishes done each day. But that’s not what I remember. I remember the cobwebs in the kitchen curtains, the fine layer of dust on top of the rusty water heater in our bathroom, the threadbare brindle carpet in our living area, the rotting apricots that littered the eastern side of our farmhouse at the end of the summer. Dad’s defective tools. Stray sheets of roofing iron, lengths of baling twine lying around. Love, neatness, value, and preciousness are good at trampling, confusing, and conflicting with one another. I experiment with that a lot in my work.

One thing to add: studying photography at a technical college in London was exactly what I needed to fill gaps, but the knowledge I gained was at odds with how I wanted to make. I wanted to be rough and imperfect. However, taking time to pick at those oppositional forces taught me useful, necessary skills. I did resist learning some things because once you learn it’s almost impossible to un-learn. I’d rather mess up through not knowing because that’s where magic reveals itself. I love not being able to repeat a gesture because I didn’t exactly what I was doing in the first place.

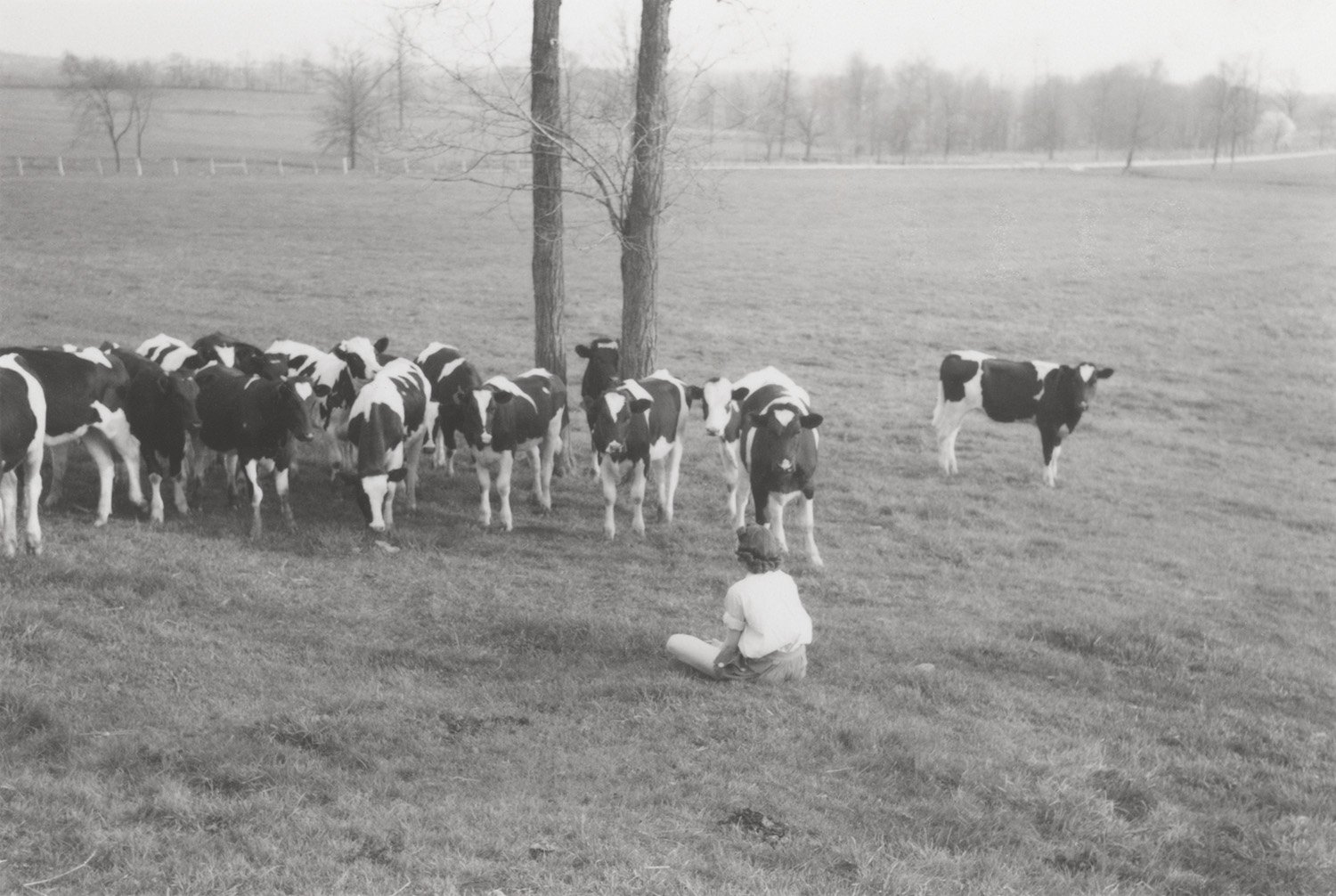

HG: On to the Dairy Character work. Tell me about the combination of your experience growing up on a dairy farm, the things you learned at an early age, and what those things began to mean to you later as an adult.

OE: Growing up on a remote dairy farm was a wonderful and challenging combination of extremes and opposites. Magical and limiting, fun and hard work, lots of hands-on learning and exploration, no concerns about strangers or getting lost. Actually, ‘getting lost’ was something I loved to try to do. Ours was, and still is a small, largely male-occupied community; there were first, second, third generation farmers; several immigrant families from The Netherlands and Ireland and Germany, all dairy farmers. Our farmhouses were sandwiched between the sand hills to the south and the Murray River to the north, which is Australia’s largest. There were no asphalt roads, no shops, no taxis or movie theaters. So, there was a prolonging of childhood on the one hand but also a very early, very direct learning of labor. I grew up knowing that information and experience was stored in our bodies, which helped us to troubleshoot and be resourceful, and now those attributes are primary, foundational aspects of my art practice. We grew what we needed; we rarely threw anything away; if someone needed something and we had it, we gave it. If someone’s cows got out, it was everyone’s problem to solve. But within this very collaborative extended family I was also aware of being a girl and what that meant for me labor-wise, yet as a first-born daughter, I was assigned jobs that perhaps I wouldn’t have otherwise, like learning to drive Dad’s truck when I was about nine years old. And I think it’s worth saying that the differences between rural life and town or city life only become more pronounced when you move from one to the other. When I went to the city for high school, culturally I was miles behind my peers. They’d heard of things and seen things and read things – books, television, films, art, events – that I had no clue about. The flip side was that I knew how to gut fish, bale hay, whistle to a fox, skin rabbits, change tires, bake pies, light fires without matches, all useful, practical stuff.

HG: When did you realize that you are a feminist?

OE: It’s likely I realized it well before hearing the words ‘feminist’ or ‘feminism’. I don’t recall anyone saying it or talking about it at the farm but I do remember earwigging on a group of male farmers one day protesting the new veterinarian in town, a woman, and one of them commenting that it [her being hired] was because of “women’s lib and all that shit”. I thought about that experience a lot when I was working on Dairy Character, so much so it ended up as one of the short stories in the book. The idea of a female being in charge of the health of most important females in a dairy farmer’s life – his cows – was at that time outrageous and unnerving to many of the men. I wish I’d known at the time how to participate in that conversation.

There are things placed onto our bodies by other people, history, and ancestry. I have numerous questions pinned to a board in my studio, two of them being: What is placed onto my body that informs my backstory? How are female bodies implements that some men try to manipulate? So much of Dairy Character is like an acknowledgement of my inability to find the kind femaleness I so desperately wanted in a place I love to this day; and that my understanding of femaleness was colored by what men told me it was.

HG: Speaking of being a feminist, Cropping Us In, has similar ideas as Dairy Character. Is there any conflict within you about how you grew up and the patriarchal world of the farm?

OE: I’m fond of the author Lewis Hyde, and in his book A Primer for Forgetting, he writes that if you want to secure a lie, you need to surround it with a moat of forgetfulness. I think for the longest of times my head was turned towards a rosy glow of nostalgia about the farm and our community; and hovering like a moth in that glow made me forget about some of the realities of that lifestyle. One of the conflicts I still wrestle with is how to inscribe both love of people and place and criticism of people and place into my work in a fair way (since I can’t be subjective). Even that word ‘inscribe’ is like a cut that creates a scar. Some scars are visible, some are not, and because I refuse to abandon my past, and because I’m not willing to accept it either, I make photographs about it, I recreate it…I’m paraphrasing Louise Bourgeois here, that recreating and reworking what is behind us can propel us forward in new ways.

In working on both Dairy Character and Cropping Us In, I read a lot about women and farming; books like Preserving the Family Farm and With These Hands, and I found myself wanting to point out that even now, rural females don’t share fully in the occupational inheritance of agriculture; they’re frequently excluded or marginalized from important resources, and this exclusion is the result of ongoing social processes of patriarchal culture. This social construction of agriculture is reinforced by certain types of myth-making, which work to disadvantage farm girls and women.

One of my favorite things about autobiography and history is that they’re not about providing answers, they’re about providing context. And so, I try to focus on that.

HG: Ah, yes, Context is so vitally important. Thank you for a lovely interview. I could go on and on with questions, but we only have so much room here. Don’t be surprised if I continue sending them to you privately.

OE: Thank you!

All images © Odette England