Q&A: Meg Handler

By Rafael Soldi | March 8, 2018

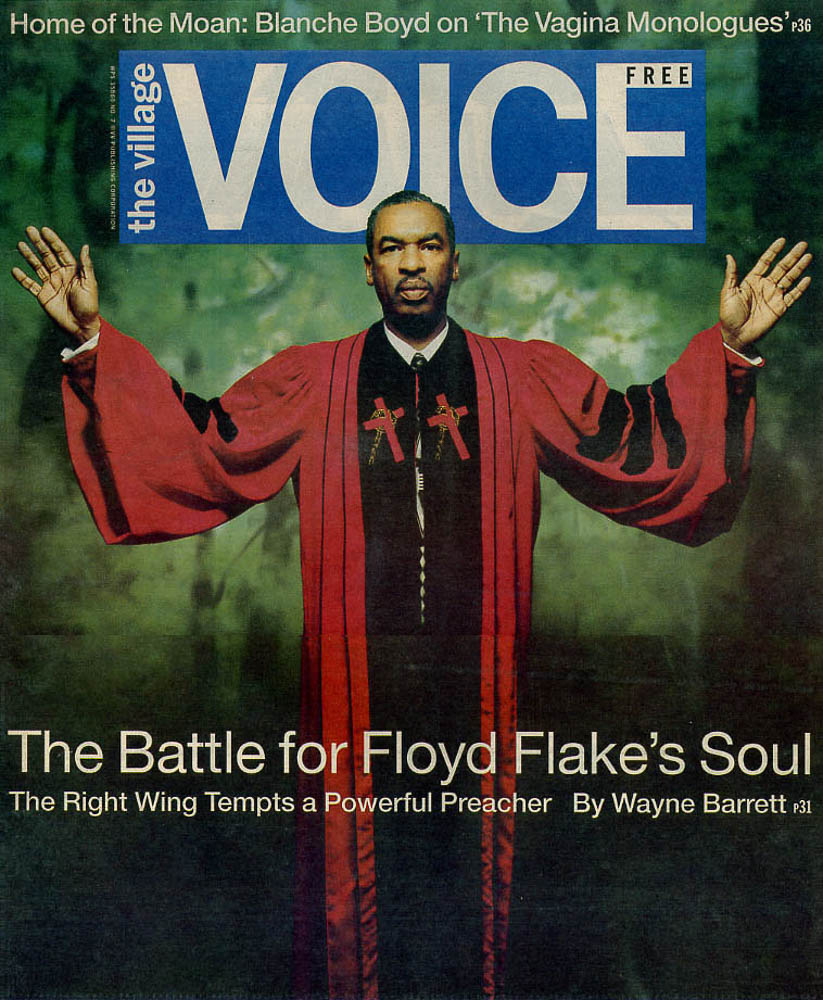

Meg Handler is Editor at Large for Reading The Pictures and a contributing editor for Hat & Beard Press. She is the former photo editor of The Village Voice. Following The Voice, Meg worked at U.S. News & World Report, Blender, New York Magazine, COLORS and Polaris Images. She has edited a number of books, including the monograph, Phil Stern: A Life’s Work, PAPARAZZI by Peter Howe, and POT CULTURE by Shirley Halperin and Steve Bloom, Mad World: An Oral History of New Wave Artists and Songs That Defined the 80’s, and DETROIT UNBROKEN DOWN by Dave Jordano.

In 2017 Meg co-curated ‘Whose Streets? Our Streets! New York 1980-2000, at the Bronx Documentary Center.

After 20 years of immersion in the photography business, and having worked with some of the great photographers in New York and abroad, Meg now lives in Chicago. Meg received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography from The Rochester Institute of Technology.

Rafael Soldi:You’ve been working with and around photography for a very long time. Currently as the Editor at Large at Reading the Pictures and prior to that at the Village Voice, New York Magazine, and others. You’ve also made some very good pictures of your own. We’ll get to go a little more in depth into all these phases of your career, but give us an overview of how you first fell in love with photography and your path from then to now.

Meg Handler: I studied photography at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), I was in the fine art program. So this is 1988 to 1990, and I didn't have a background in photography yet but what I had looked at as a kid was Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and Life magazine. So my inspiration was contemporary documentary photography, and the program that I was in was resistant to that. We were encouraged to do conceptual work but I loved having a Rolleiflex around my neck and making portraits with it.

When I went to New York after school the most natural place for me would be at the Village Voice because it was progressive and I aligned with that—it was independent, it was outspoken, and it was carrying on the same tradition of the photography that I loved. That was in the mid 90s and I had decided early on that I didn't want to make a living as a photographer but I wanted to work with photographers. So I did my work on the side photographing what I wanted and had a job as a picture editor.

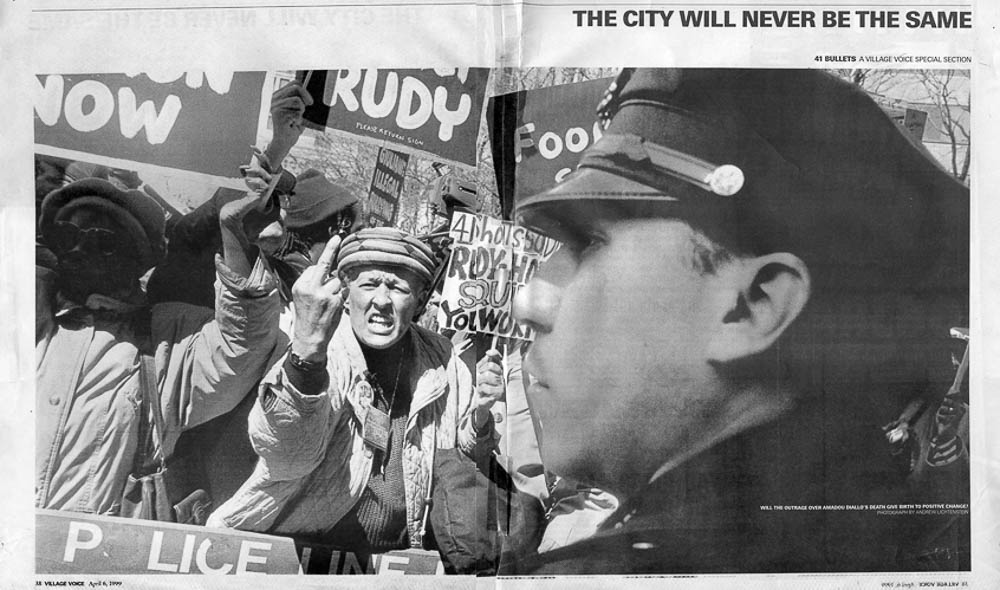

RS: So you land at The Village Voice in 1995. By now 31,500,000 HIV/AIDS cases have been reported in the US, Bill Clinton is in office. Every era has its defining moments, and as a photo editor you get to direct how those moments are seen and consumed. What was it like making those choices in a paper like The Village Voice post-80s and before the new millennium and 9/11?

MH: When I got to New York in 1990 we were in the midst of the Gulf War. I grew up in a upper middle class suburb outside of Detroit. I didn't have any experience with activism or demonstrations or protests. That's where my interest in crowds and looking at how people gather came from. I was interested in how people spoke their minds. Alternatively, the Gulf War "Welcome Home parade" was interesting to me because I had historic photographs in my head, Diane Arbus, etc. You know, we consume history through pictures and so to be part of that for me was important. In 20 more years we're going to talk about what that Gulf War homecoming parade was like, what it felt like, what we saw.

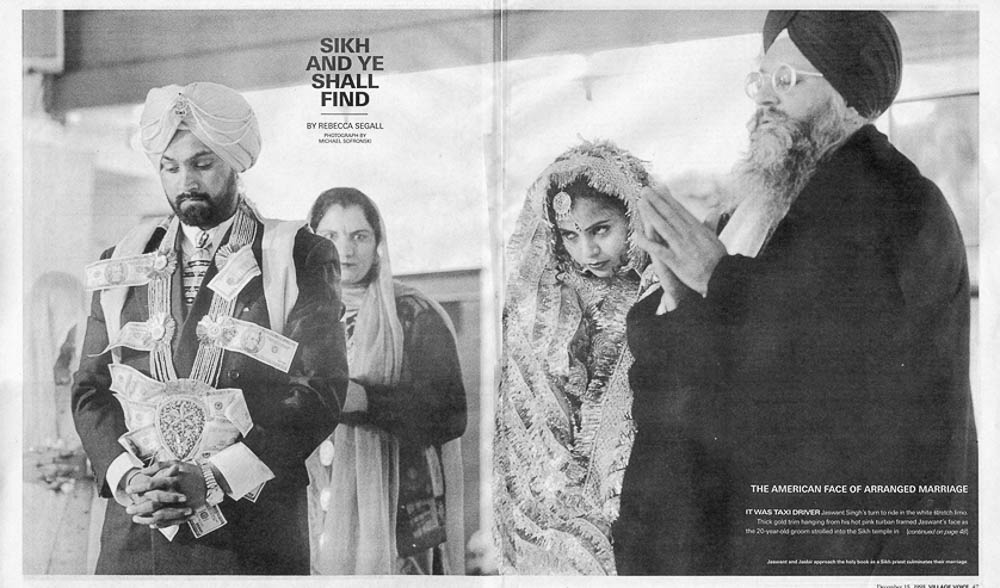

Once I got to The Voice I had already been living in New York for about four years and I read the paper every week. It was my goal to get in there and I felt I was the right person for it. I wanted to give opportunity to young photographers and work with people like Sylvia Plachy. One of my goals was to find the right person for the right assignment. Because our stories represented a diverse makeup of people, we needed to make sure our photographers were diverse too so the story was told from the right perspective.

RS: What is one of the most unforgettable assignments you worked on?

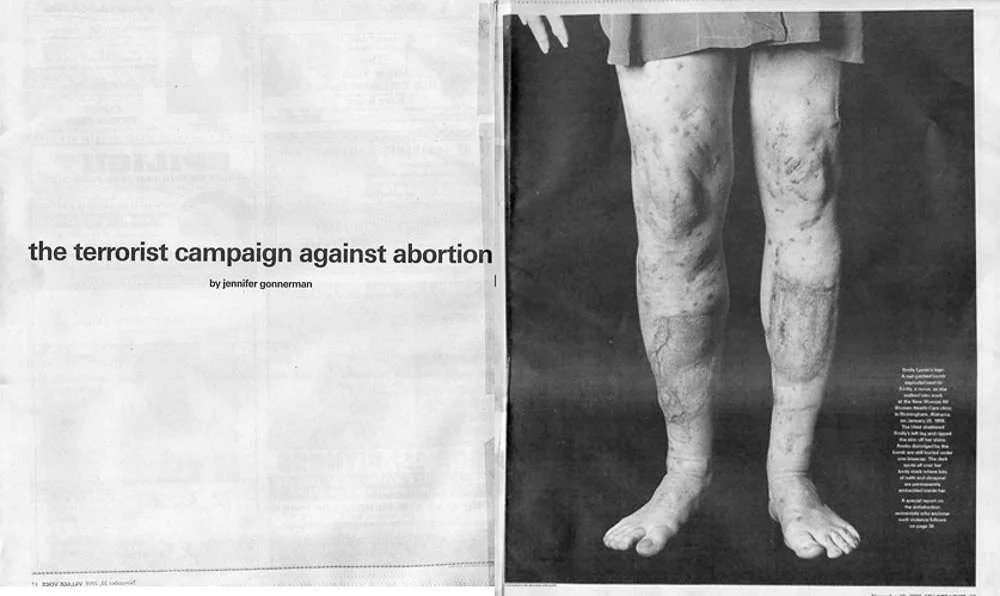

MH: Did you see a scan of a spread on my website that featured a photograph of a woman’s legs?

RS: Yeah, I was going to bring it up, it’s such a powerful photograph!

MH: That woman, Emily Lyon, was a survivor of an abortion clinic bombing, in Birmingham, Alabama. She worked there and she was walking into work and they blew up the clinic. She had skin grafts all over her body.

The conversations was, you know, how do we really send the message of how evil and violent and ugly this movement is. The 90s were a hotbed of reproductive rights activism, and they were also really violent. Doctors were shot and killed, clinics were blown up. By the time I had gotten to The Voice I had already been photographing the pro-choice and the pro-life movement, I’d spent years before looking at that. So this was of particular interest to me.

Image on The Village Voice by Melissa Springer

RS: What kind of impact did it have?

MH: We sent Melissa Springer to make this picture and it had a huge impact. This is all pre-social media so I don't recall what the letters said, but all of us knew that this was the way to tell Emily’s story. We got some letters saying, that's really graphic, or, thank you for publishing that photograph. And I think it was probably more that, people were grateful and respectful that we would take that risk. There was a time when you did not cut the heads off of people in a portrait.

RS: And that hand, it’s brilliant!

MH: Oh, the fingers. I mean, this was risky. It was risky because it was graphic. It was risky because we weren't showing her face.

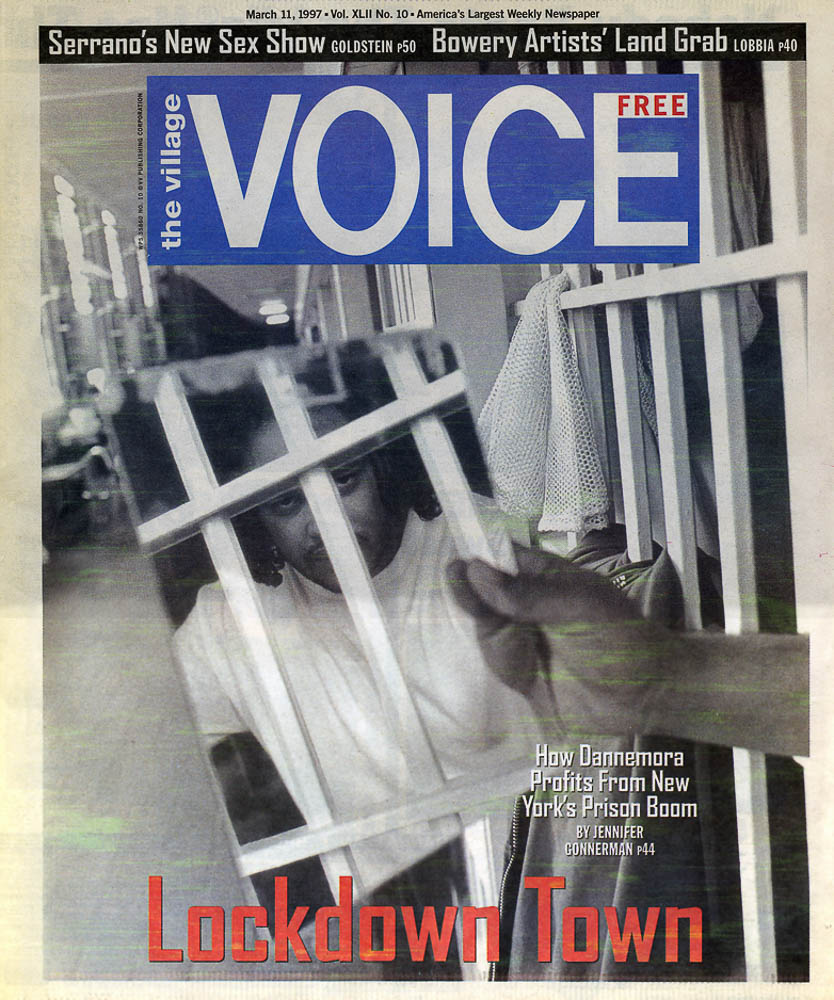

Some people felt cutting off the face was removing her dignity, and I can see that reading of it. But I just think that this was a really creative, impactful, important picture. The woman who wrote the piece, Jennifer Gonnerman, now writes for The New Yorker, it was her article that changed the rules at Rikers Island. [Kalief Browder committed suicide after he had been held in solitary at Rikers].

Celebrities were cool to photograph, but this was something else. This is the most important picture to me.

Opening reception for "Whose Streets? Our Streets! New York City 1980-2000" at the Bronx Documentary Center. Photo by Edwin J. Torres (source)

RS: So, tell me about “Whose Streets? Our Streets! 1980-2000,” how did this come about?

MH: I personally had photographed a lot of demonstrations in the 90’s. There was a group of people who were also shooting demonstrations and they were all freelancers. Most of us were politically involved progressive thinkers.

At that time there was a progressive photo agency called Impact Visuals that existed from the mid 80s to the mid 90s. There is a group of about 20 photographers who were involved in Impact. So in 2015 I got contacted by Tamar Carroll, a historian and professor at RIT, my alma mater. She was working on a book on 100 years of activism and social movements in New York. She wanted to license some of my photographs, but as we were talking I brought up a lot of names—I naturally wanted to help and connect her with this group. As we talked I thought, this is a show. This is a show and I have the perfect place for it.

We put a proposal together and pitched it to the Bronx Documentary Center (BDC). For me, from conception, the show had to be at BDC because it’s a community organization. It didn’t fit into a traditional museum or white box gallery. Once BDC agreed to do it, it became a very personal, all-absorbing project with twenty eight photographers. The reason we had 28 photographers was because we wanted to have all the boroughs represented.

We could not predict the results of the election. This show was scheduled to open on January 15th, of 2017, and through the fall we thought it was going to be a celebration. We thought it was going to be a party. We thought, here we are 20 years later and we’ve made change and maybe these pictures are partly responsible. We thought we’d be celebrating our first female president.

After the election there now was this paradigm shift. We were wondering how to make this show respond to current events, and then the Women’s March happened the weekend of after our opening. I think all of us realized that the work we did in the early 90s inspired the work we're all doing now. I’m now photographing activism here in Chicago.

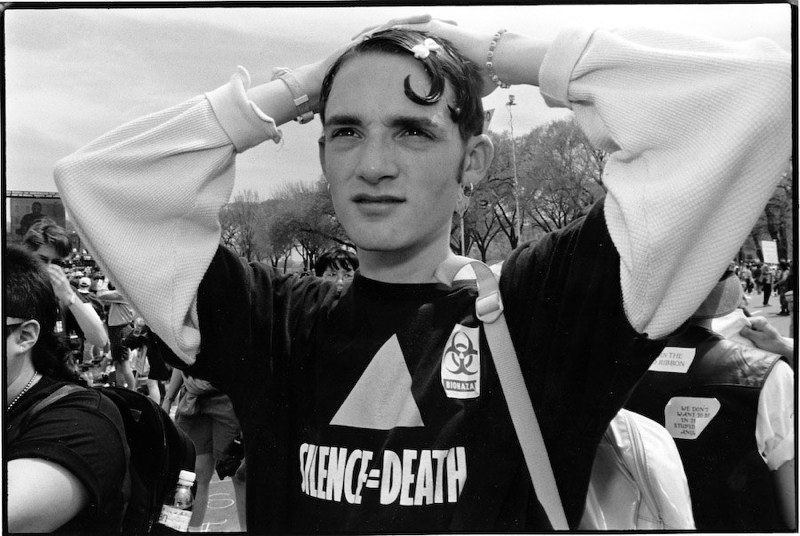

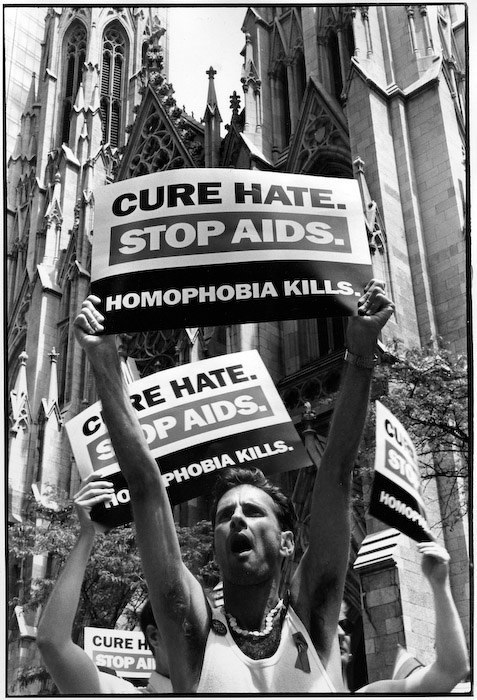

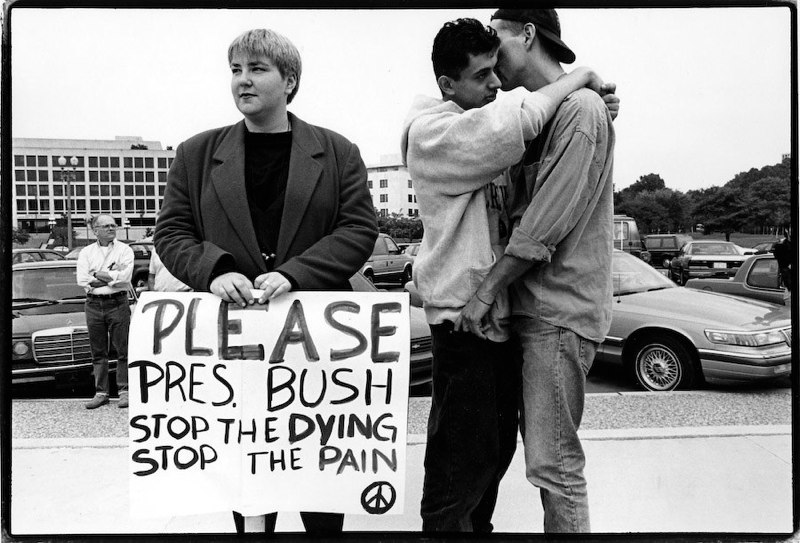

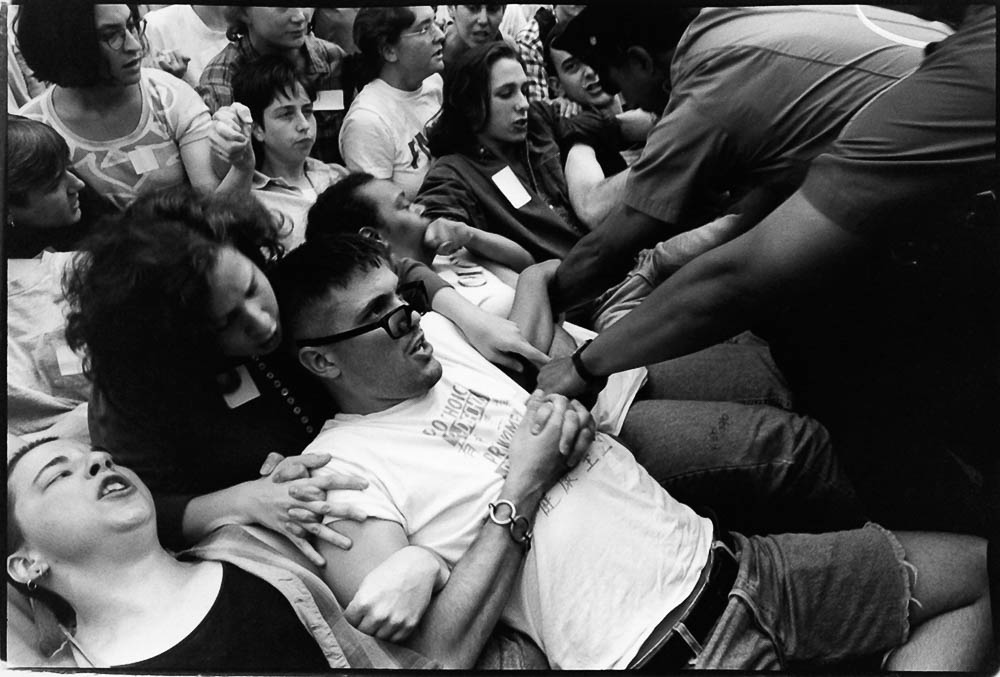

© Meg Handler, ACT UP Demonstration

RS: Your images of the ACT UP demonstrations are so powerful. A lot of that sorrow and anger and frustration feels very familiar today, with Black Lives Matter (BLM).

MH: You know, they're both epidemic. Deaths from AIDS, death by cop had and have created an environment where people have to put their bodies on the line. That's how I see BLM, they’re not just marching once a year. They’re activists every single day. And when you put your body on the line, you’re getting arrested almost every week. The ACT UP members, BLM group—this is historical activism. Here on the South Side of Chicago, almost every family has been affected by gun violence. There are churches and groups setting up vigils and demonstrations every Sunday.

RS: Many of the pro-choice rally images remind us that not much has changed. At the time I’m sure all those rallies seemed important, but now these are images of truly historic moments of resistance and revolution. Did you understand then how important these acts you were witnessing were?

MH: My intention was obviously to document history. But only hindsight provides you with the depth of understanding. I photographed an action in Washington D.C., where members of ACT UP brought the ashes of their loved ones, and at their request, the ashes were thrown on the White House lawn.

That was happening as police on horses were coming up against the crowd. It was very dangerous and heart-breaking. Think about how powerful that concept is. I don’t think it’s never been done again. So, I knew it was important, but I didn’t have the foresight then to understand how important it was.

© Meg Handler, ACT UP, Ashes Action, Washington D.C., 1992.

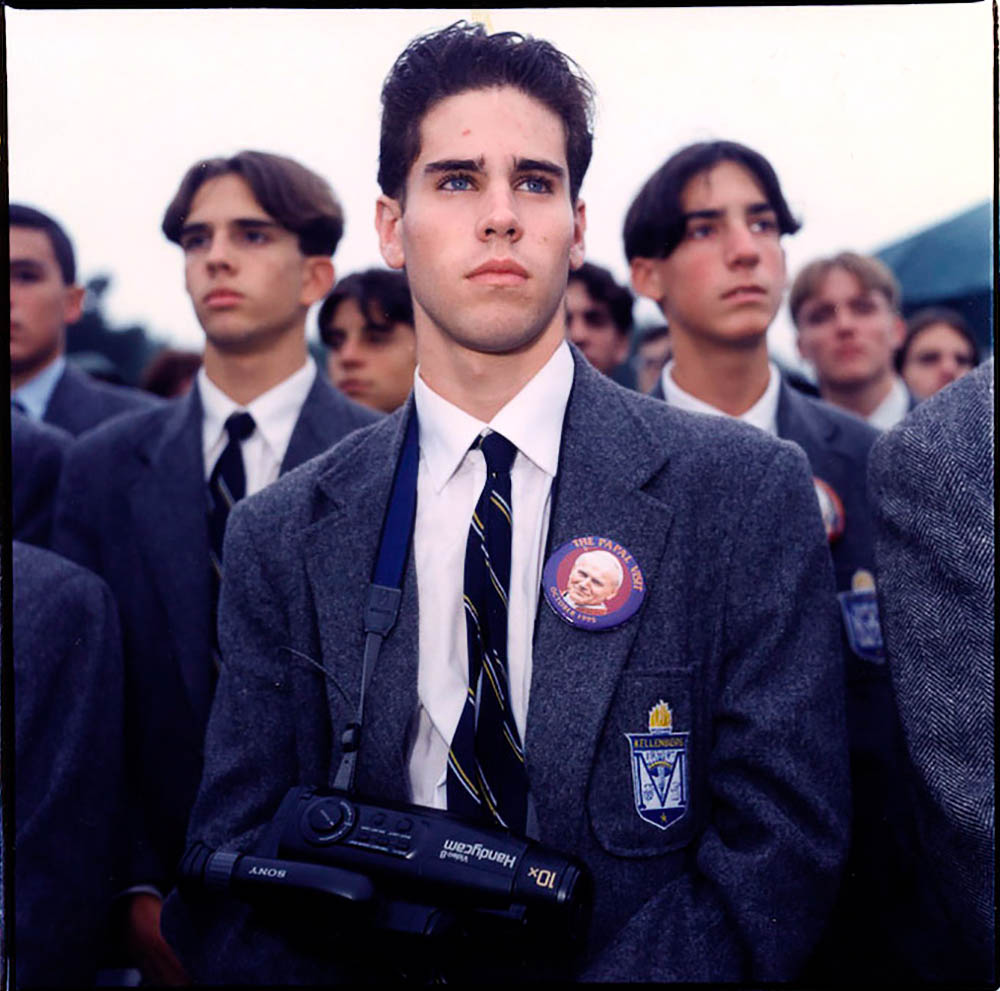

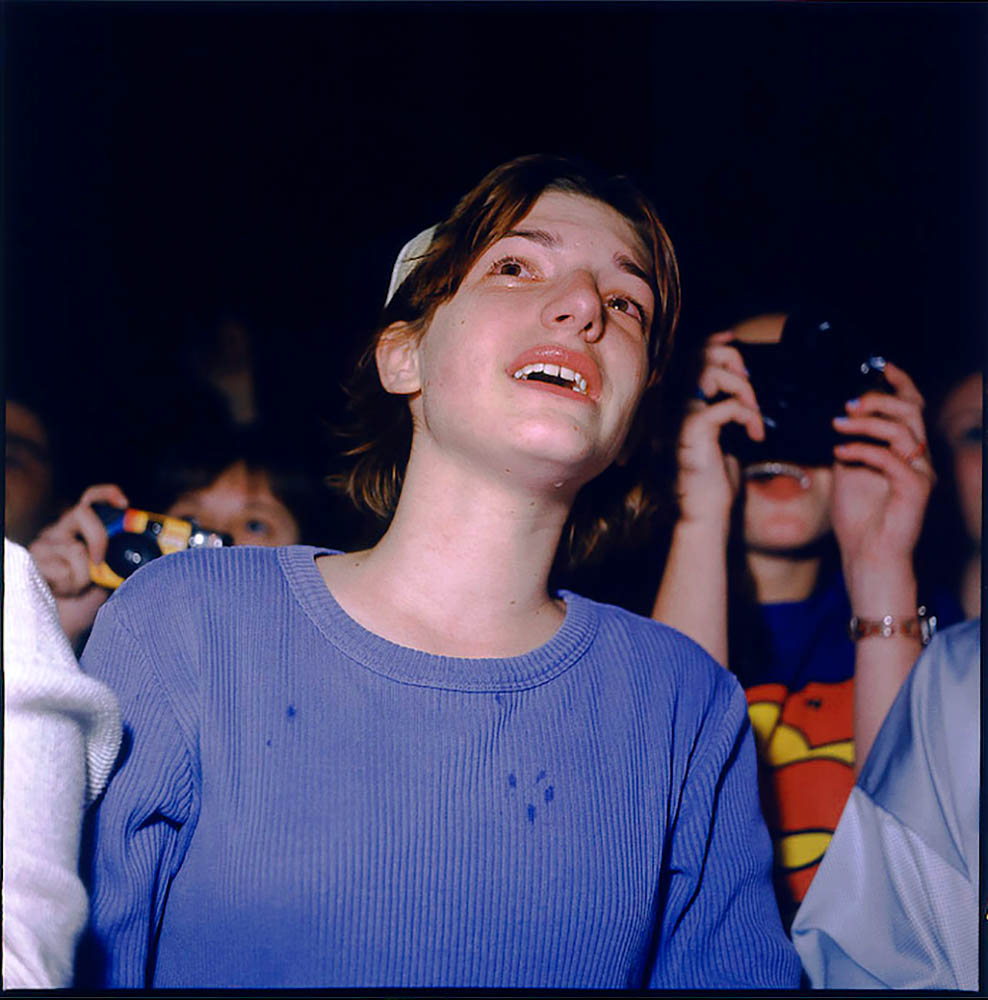

RS: I love your photos of fans—at rallies, pope visits, Elvis death week, sporting events, concerts. They are so utterly of a specific American zeitgeist and show our country’s all-in attitude and cult obsession that is the root of our divisiveness. But these images also clue us into a country that is so young, naive, impressionable, still grasping to form an identity in a global civilization that is thousands of years ahead identity-wise. At the same time, devotion, worship, the need for a guiding light and optimism are all such universal notions. Can you tell me more about what drew you to these subjects?

MH: OK, well, first of all, everything you just said is mind-blowing for me because it's exactly what I want people to see in those pictures. I had been photographing what I called “religion in the streets”, and in in a way I considered the pro-life movement part of that too. I had been doing that for a year or so when I saw on the news that there was a Jesus sighting, in Washington Heights.

© Meg Handler, Jesus Sighting

People were seeing Jesus in a bathroom window. I ran up there and people were in awe. I mean, they were out of their bodies. I'd never seen anything like it. The irony is that I did not see the image of Jesus Christ, it was condensation between two pieces of glass. And I realized in that moment that people see what they need to see and that it is driven by a deep commitment and relationship to whatever their personal iconography is. Then I started to see how people looked, at a Garth Brooks concert in Central Park (there, I photographed a man holding a Confederate flag)—This pop worship is just something that was purely American to me. So when I saw this Jesus sighting I thought, OK, if people look like this looking at a bathroom window, what do they look like when they're seeing the pope? What do they look like when they're going to death week at Graceland? What do they look like when they see Gillian Anderson at a an X-Files convention?

These reactions come from the depths of who these people are. And after going to many events it proved to be true that people will lose themselves over anything and anybody if they convince themselves. The old ladies at Elvis death week and the people at the Garth Brooks concert in Central Park looked exactly the same as the people seeing the Pope. The commercialism aspect of these events was also important to me and I tried to include some of the merchandise in the photos.

RS: I love the Pope jacket, it’s super punk and really unexpected.

MH: I love that picture so much. Here you have a 13 year old girl a teenage girl in a Pope patched jean jacket, what could be better?

© Meg Handler, Papal Visit

RS: I’ve heard that today we consume more images than words, which would make photography the language of today. Visual literacy is paramount, we should be teaching it in schools. I love what you and your team are doing at Reading The Pictures. What is this platform about and what is your role there?

MH: So, first, yes, I think that that that statistic is is probably true, everything is coming at us so quickly. It’s important to have a culture that is visually literate, that understands what they're looking at.

I started working with Michael Shaw, the publisher of Reading The Pictures, about five years ago. I was originally producing the salons, which are online panel discussions on different subjects in the news. Day-to-day, I research news photographs that I think would be interesting to write about. I create assignments for our contributors and work with them. Most of our contributors are academics, they teach rhetoric, theory, semiotics, and communication so they come at news photography from a critical perspective.

www.readingthepictures.com

It's a challenge to plow through everything and figure out what's important, what people want to read about or look at deeper. Having a 27-year background looking at pictures, I’m critical with what I choose to put in front of contributors or what I choose to put in front of my publisher.

When the site began, there were daily essays on one or two pictures. But as our way of absorbing information has changed we had to change and we've created a bigger presence on Twitter and Instagram. Those platforms really work for us because everyone is used to looking at pictures with a description below, which is what we were already doing.

I have a great publisher who encourages my creativity and my strengths, from him I've learned how to think about pictures differently. Reading the Pictures is so important. In an age where newspapers are firing their photographers and asking writers to carry a camera, every day we’re justifying why photographs are important.

RS: What other projects are you working on right now?

MH: In addition to my work with Reading the Pictures, I’m doing some editing for Hat & Beard Press, a small press out of L.A. that does art and photography books. I’m also working with historian Rick Perlstein, his focus is on the rise of the conservative movement. Reaganland, is the next in Perlstein’s series (Nixonland, Invisible Bridge). I'm doing the photo research and editing, and copy editing.

RS: That’s exciting! Thank you for taking the time to chat.

MH: I'm glad you took the time and I'm glad we could chat. Thank you so much. Really appreciate it.