Q&A: Marisol Malatesta

By Rafael Soldi | October 11, 2018

Marisol Malatesta works and lives and works in Treviglio Bergamo. She studied at the Universidad Católica del Perú where she graduated in Fine Art (Painting) in 2000. She received a Post Graduate Diploma and a MFA from Byam Shaw School of Art at Central Saint Martins in 2002 and 2003.

Her recent solo shows include: My nose grows Now! Luis Miroquesada Garland Gallery and Sala 770 at the Ricardo Palma Cultural Centre, Lima 2017; Orange beats Blue, Blue beats Yellow, Yellow beats Orange at Maquis Projects Gallery, Izmir 2014; AΔB at Spazio19, Bergamo 2014; Corrosion of the Character at Vegapunk Projects, Milan 2014; Parts of the Face are Not Likely to Move Much Either at the Peruvian Embassy, London 2010.

Her work has being included in group shows and projects such as: Art Recipe Book Project 2018 Arts University Bournemouth; DROP: Beyond Boundaries, Looking Down on Art, Goodman Art Centre, Singapore, 2018; Messages From a New America, The 10th Mercosul Biennial, 2016; An Argument for Difference, TSA Gallery, New York, 2016; Connecting Worlds at The Drawing Room, London 2014; Remesas: flujos simbólicos / movilidades de capital at Fundación Telefónica, Lima 2013; The Europe Triangle at the Royal College of Art Gallery by The Goethe Institute, London 2013. She was selected for the Jerwood contemporary Painters 2007 exhibited in London, Cardiff and Manchester.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Marisol, thanks for chatting with us! Fill us in on our trajectory, from Peru to the UK to Italy. What brought you to these cities and what role have these transitions had on your practice?

Marisol Malatesta: I grew up in Ica, Peru, a small city south of the capital. It was like growing in a Magic Realism environment, a city that celebrates grapes and wine, a place where witchcraft practices had a strong influence in the idiosyncrasy of the people as well as religious processions, earthquakes and legends. This syncretism between religious and pagan is something I grew up with and it is present in my work.

Painting became an obsession since very early age. I use to attend a painters group in Ica when I was thirteen, classical music was played in the background, it was amazing.

So the most natural thing was to go to Lima, the capital, to study at University. I was sixteen, clumsy and shy. In Lima I finished a bachelor’s degree in painting, which focused on technical skills; this is something that forged my practice and that continued to define my work through out my career. After finishing Uni all I cared about was to go to Europe to see the paintings that I saw only in books. I obtained a scholarship to study a Post Graduate and an MA in London, and I ended up staying for 15 years. Now I live in Treviglio, a city between Milan and Bergamo where I continue my practice as an artist and recently me and my husband Simone have started Tilde a project that involves ancient grains, baking and art.

A lick and a Promise. Oil on Canvas 190 x 170 cm, oil on linen, between 2010 and 2015

RS: How has your training in traditional techniques influenced your work, and how have your more conceptual explorations manifested through these methods?

MM: I come from a very traditional art education in Lima. An education that gave priority to skills, with a strong technical approach—there I specialized in painting. When I say painting I mean painting: hours and hours and years of training. Sometimes it felt pointless, it was very much an exercise of contemplation while there were very serious and complicated social and political contexts outside the university walls. But we all learn perseverance and strategies to canalize frustration. It is not until later that I realized that in that kind of practice there is a potential political approach, one that questions technology and what is that makes us human. When you are forced to that kind of training all you dream of is to leave and to discover new ways of expression. I went to London. That was different; somehow I was confronted with a system that focused on more conceptual approaches to art making. It forced me to take some distance from what I was doing and it made me much more critical towards my own practice.

Italy now is something I am still trying to understand; it is somehow going back to the beginning; back to traditions. I am enjoying the beauty of the cities, art history, food, and I find interesting the obsession with fashion and design. It is having an effect on my work but I am still processing it.

RS: In what constitutes and unusual relationship, the abstract and the figurative are somewhat symbiotic in your work. Can you expand on this and other contradictions within your work?

MM: Figures tell stories but abstract forms speak for themselves, I find myself constantly in the dilemma of negotiating the two.

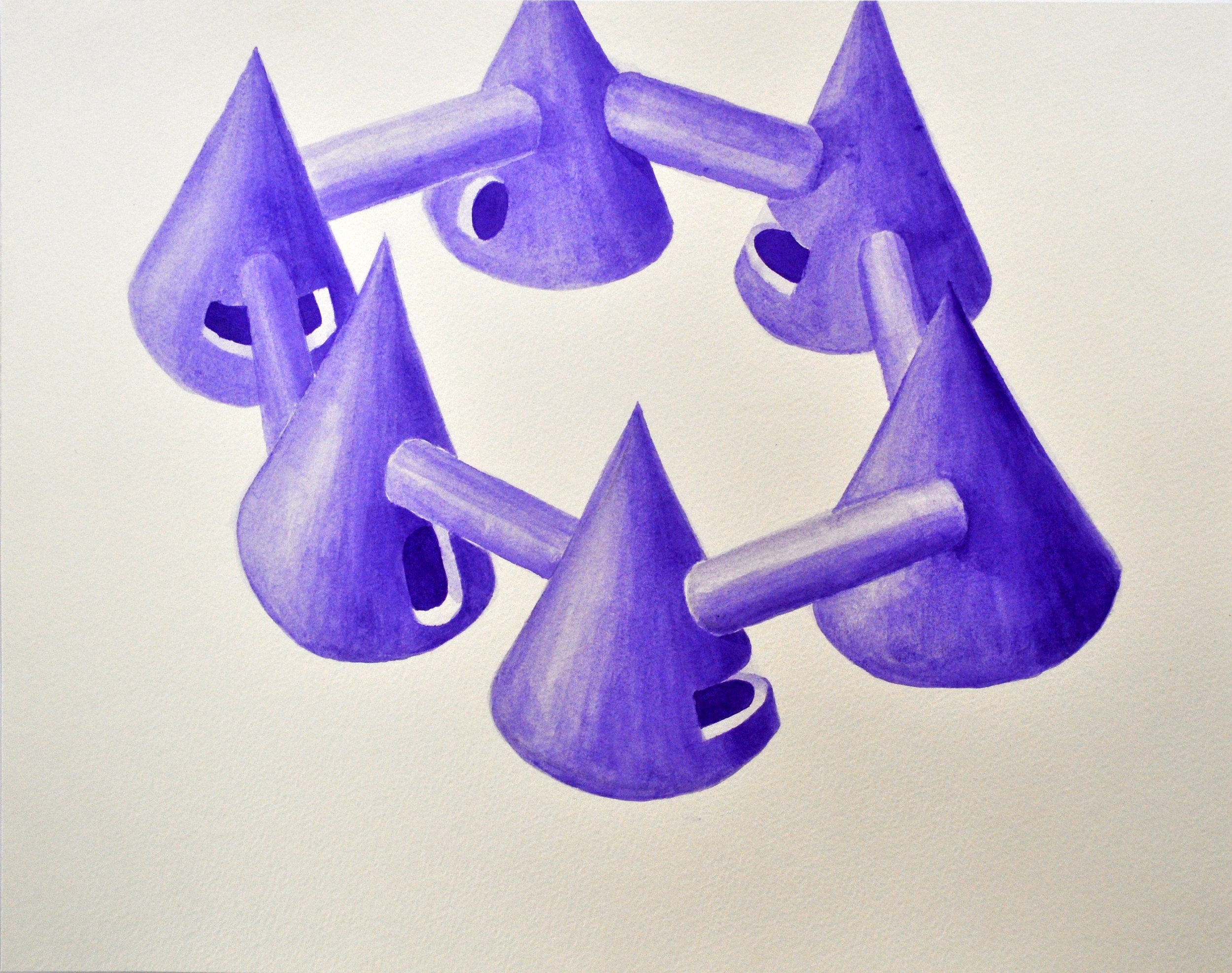

I use the nose to represent a face and that element opens different associations, symbolically it refers to lies and formally to a cylinder that also reads as a phallus, therefore suggesting narratives of sexuality and power. These forms are both abstract figures and figurative representations.

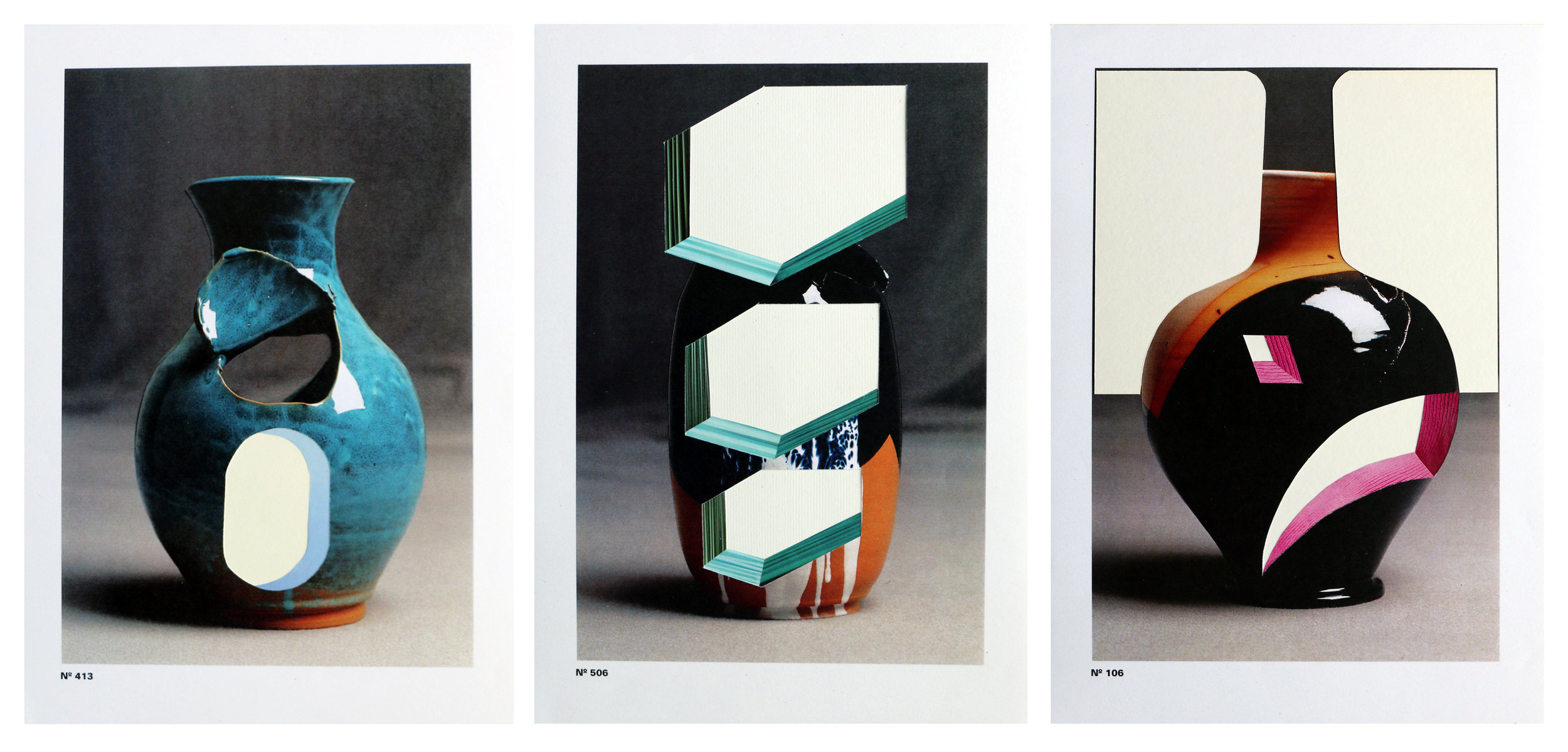

I like playing with forms by creating oppositions—for example, oppositions between functionally and futilely, most of my ceramics for example loose their purpose by means of holes or peaks placed in wrong places.

In my practice oppositions try to coexist, a compulsive but also a very controlled technique go hand-in-hand. In my paintings I try to achieve painstakingly tridimensional effects but layering makes the opposite effect, it becomes a heavy surface more to do with accumulation and time than just pure optical illusions.

I think is becoming the ethos of my work this fixation with failure and process.

~o~o, 30 x 40 cm oil on linen, 2016

RS: The art world can often feel intimidating. How have you carved out a place for yourself that feels both challenging and nurturing?

MM: By keeping a respectful distance, I think, and also by creating my own agencies. I really enjoy doing projects with other artists and independent curators; I don’t depend solely on the art market.

The bakery we just created is a platform for research and artistic collaborations, but is also economically sustainable! This balanced between time for practice and economical survival is something that is not talked about that often, but it is in the core of art practice. All artists are always negotiating the two. I guess one has to decide what kind of compromise to make.

I have also taught at the Arts University Bournemouth for more that 6 years before coming to Italy and now we organize a residency here in which the bakery is involved. Teaching is both invigorating and economically rewarding.

RS: Over time you’ve created language of your own, you employ primitive shapes and forms that are both lighthearted and humorous but often mask a darker sub-context. Where do these come from, what role do they play, and what impact have you found them to have?

MM: I think this has happened with years of making. I have gone through different periods and explore different subjects and materials but somehow there are recurrent themes that keep coming back, like the mask and the humor. I am interested in primitive forms, basic objects that try to explain the unnatural—an underworld. I don’t think I want to be cynic with my work as I think cynicism often masks an incapacity to have a position towards an issue. Humor on the other hand only appears when something is wrong, unsettling, or threatening but at the same time is ok; this is something I’m interested in.

AΔ, Brick dust and acrylic on canvas 45 x 45cm and White primed canvas 50 x 70cm. AΔ, Sanded brick, 4.5 x 21 x 11cm with triangle (sanded brick, 2.7 x 3cm

RS: Some of your work features futile narratives performed by masked of headless figures. I find these fascinating... a little funny and a little disturbing. Can you elaborate on this strategy?

MM: These masks are really concrete objects that read as faces. I am interested in the psychology behind not having an identity. Also I am interested in creating a stage, a theatrical representation of reality. Masks work perfectly.

I am also interested in the mask as a pure pictorial representation. I came across a book: Charles Le Brun (1619/1690) ‘Expressions of Passions,’ which is a detailed study on how expressions should be depicted in painting, for example: ‘Wonder: ...so the face also undergoes very little change in any part, if there is any change, it is only in the raising of the eye brows, but the two ends of it will remain level; the eye will be a little more open than usual, and the pupil will be situated equidistant from the two eyelids, and immobile, fixed on the object which causes the wonder…’

I loved how concrete and abstract this descriptions are, they influenced some of my most iconic paintings of masks.

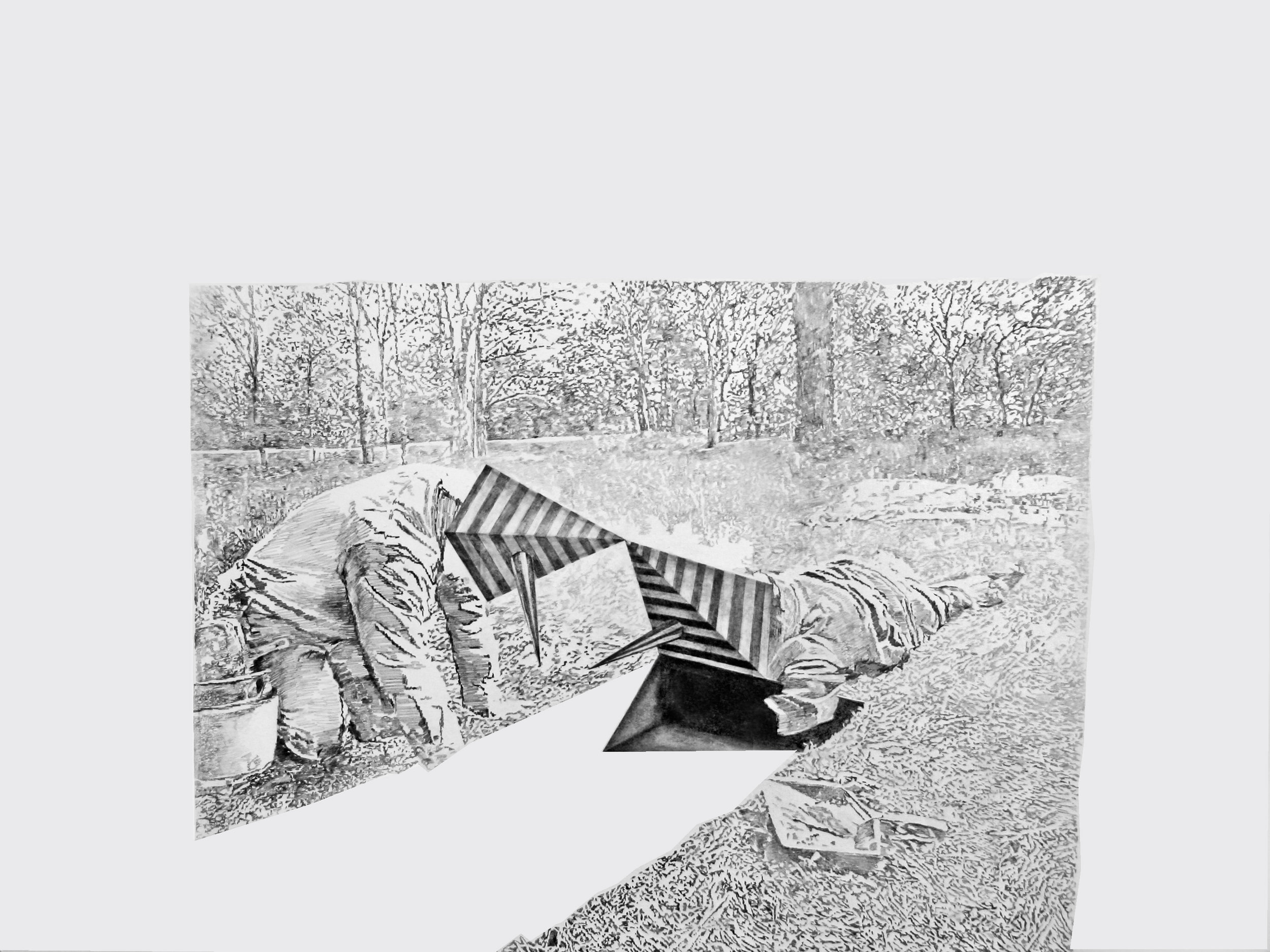

Equivalent 0, from series AΔB, 40 x 40 x 80cm, ink on two papers weaved, 2014

RS: Talk to me about your newfound relationship with bread, and where life is headed at the moment.

MM: Bread and ceramics have a lot in common, they need to be shaped mainly by hand and baked in high temperatures, also both come from natural resources. Bread and ceramics are ancient’s practices that served ritualistic but functional purposes in different moments and cultures. So it was a natural process to fall in love with bread.

Simone, my husband is a master baker specialized in sour dough bread; thanks to him I started to discover bread few years ago. Fermentation is an incredible thing: it is basic but also universal, is concrete but also poetic. In some ways bread has shacked my grounds, it is difficult to explain but sometimes it seems more relevant than art—it made me questioned my practice and the futility of it. We are in a historical crisis of food production, and this makes bread so relevant.

We joined forces to create Tilde. Tilde is a bakery as well as a platform for research, sharing and collaboration.

In Italy there is a revolution of ancient grains. These are grains that were produced before the industrial revolution and that are not genetically modified. These flours are difficult to work with but are perfect for natural fermentation. We also work directly with stone mills; the ethos behind Tilde is to have the control of the full circle of production (agriculture, mill, baking, costumer). At the same time we think of Tilde as a cultural place for art and research. We held a residency with art students from Bournemouth University. They come to experience bread-making and then do a show (always bread-based). We started two years ago and is full-on, tiring at times but so much fun. We hope to collaborate with artists as well as food experts, producers, etc.

Though my love for painting is stronger than ever. Questioning doesn’t mean that you stop.

Life Extension, 30 x 40 cm oil on linen, 2016