Q&A: Mariela Sancari

By Rafael Soldi | April 14, 2022

Mariela Sancari was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1976. She lives and works in Mexico City since 1997. Her work revolves around truthfulness and fiction in images, using personal narratives to explore the boundaries of the scope of photography as a means of representation.

Winner of the VI Bienal Nacional de Artes Visuales Yucatan 2013 and PHotoEspaña Descubrimientos Prize 2014, her work was selected for the XVI Bienal de Fotografía from Centro de la Imagen and received an Honorable Mention in XI Bienal Monterrey FEMSA. She received an Honorable Mention in the Official Selection Artemergente National Monterrey Biennale 2012. She has participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions in Buenos Aires, Guatemala City, Mexico City, Oaxaca, Sao Paulo, Athens, Barcelona, Belfast, Bratislava, Busan, Houston, Jaipur, Londres, Los Angeles, Madrid, among others. Her work is part of the Instituto de Cultura de Yucatán Collection in Mexico, Centro de Artes Alcobendas Collection in Spain, the Joaquim Paiva Collection in Rio de Janeiro, Fundación Televisa and Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City and other private collections.

[ESPAÑOL]

Mariela Sancari nació en Buenos Aires, Argentina en 1976. Vive y trabaja en la Ciudad de México desde 1997. Su trabajo gira en torno a la identidad, la memoria y la veracidad y la ficción en las imágenes. Utiliza narrativas personales para explorar los límites del alcance de la fotografía como medio de representación.

Ganadora de la VI Bienal Nacional de Artes Visuales Yucatán 2013 y del Premio Descubrimientos PHotoEspaña 2014, su trabajo fue seleccionado en la XVI Bienal de Fotografía del Centro de la Imagen y recibió Mención Honorífica en la XI Bienal Monterrey FEMSA. Obtuvo Mención Honorífica en la Selección Oficial Artemergente Bienal Nacional de Monterrey 2012. Ha participado en numerosas exposiciones individuales y colectivas en Buenos Aires, Ciudad de Guatemala, Ciudad de México, Sao Paulo, Atenas, Barcelona, Busan, Bratislava, Houston, Jaipur, Los Angeles, Londres, Madrid, entre otras. Su obra forma parte de la Colección del Instituto de Cultura de Yucatán, del Centro de las Artes de Alcobendas en España, de la Colección de Joaquim Paiva en Río de Janeiro, de la Fundación Televisa y del Centro de la Imagen en la Ciudad de México.

Scroll down for interview in Spanish.

Baja la página para leer la entrevista en español.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Mariela, thank you for chatting with us.

Mariela Sancari: Thank you for the invitation, happy to be in conversation with you.

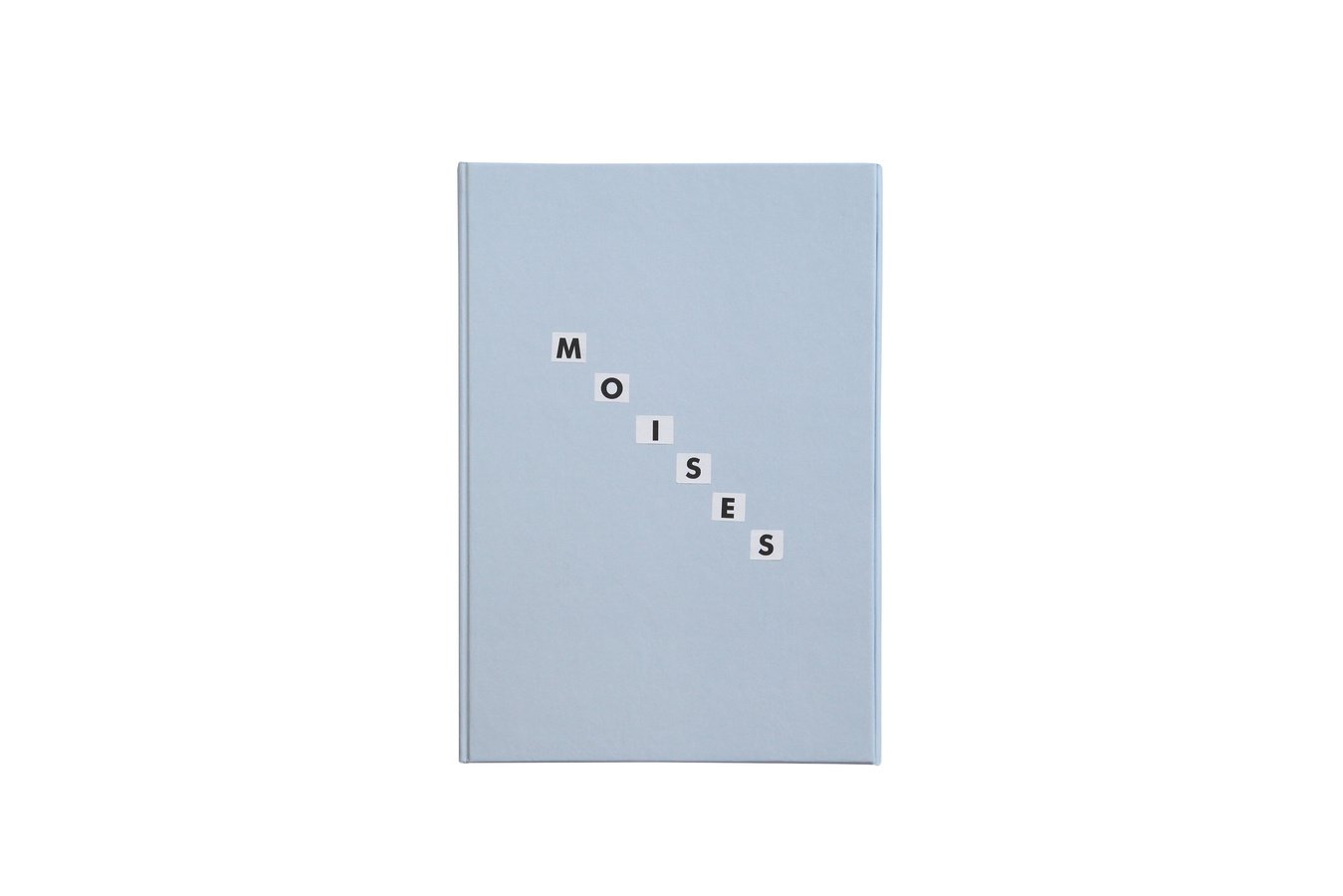

RS: I’d like to steer our conversation today toward your recent book projects, both their conceptual frameworks and the book itself as a medium. I want to briefly touch on Moisés, which is an earlier project that received a lot of attention. I want to start there because it seems it laid a foundation for much of the work you’re doing today. Can you briefly explain the premise behind Moisés and what are some of the big picture tools and strategies from this project that continue to be a driving force in your practice?

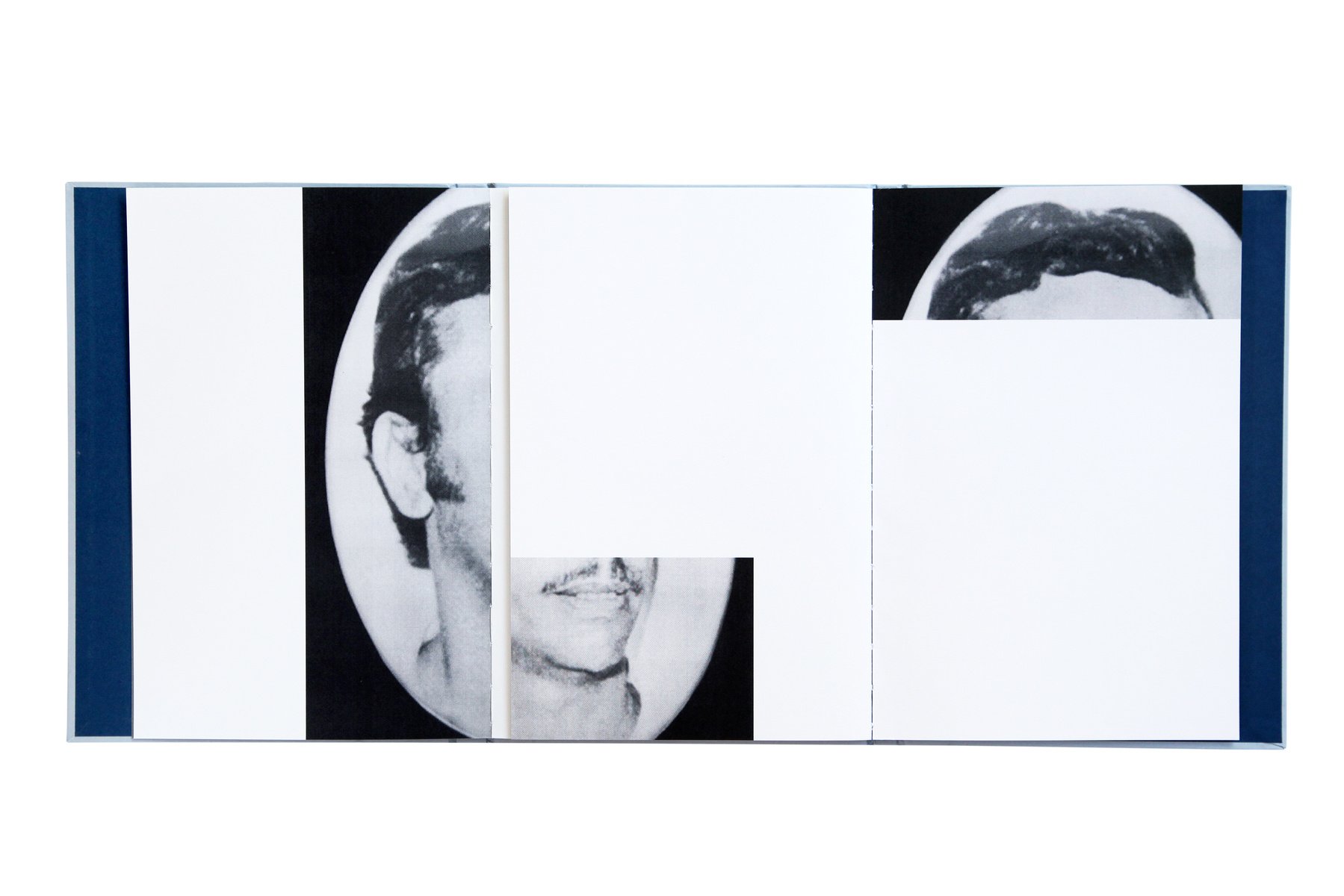

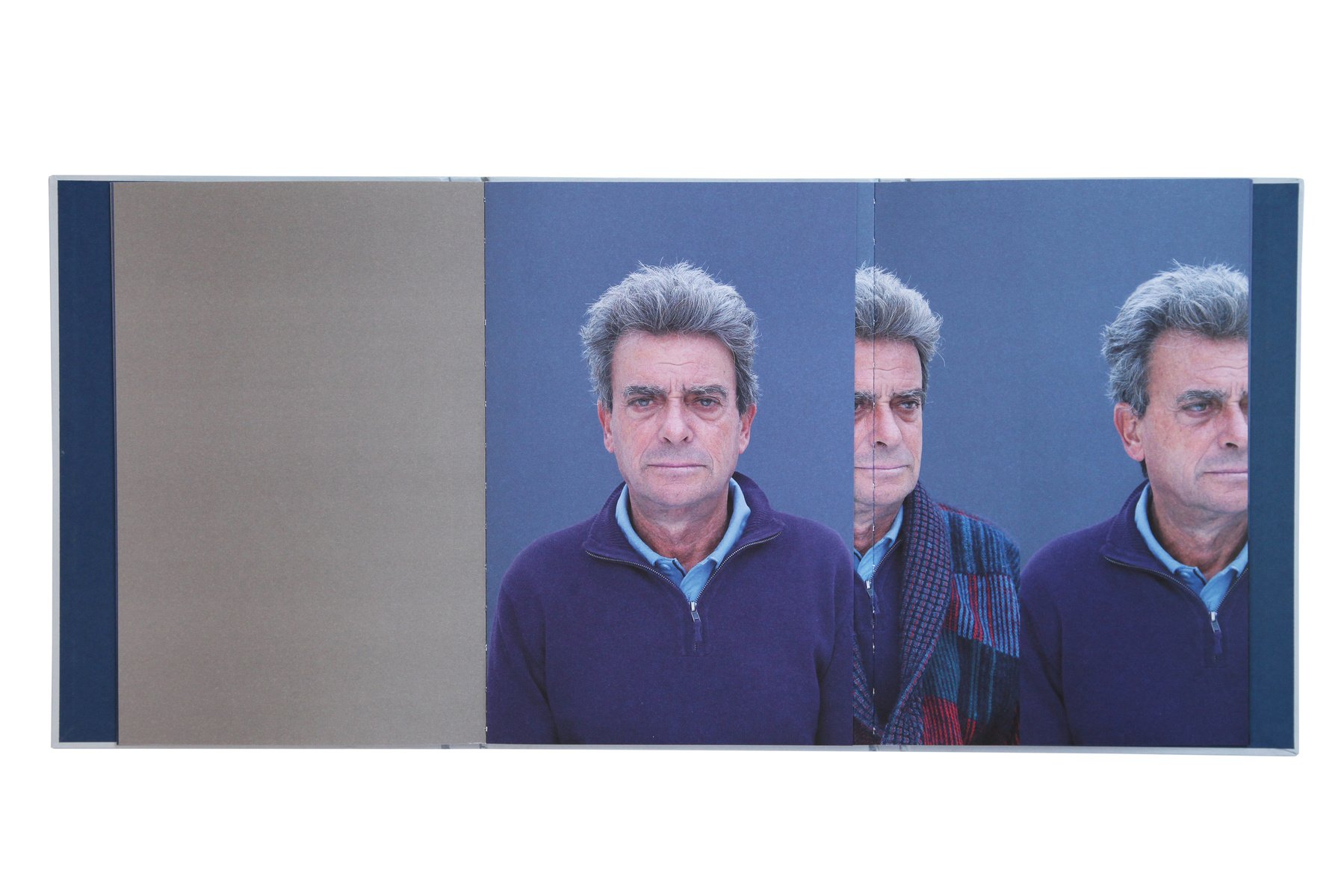

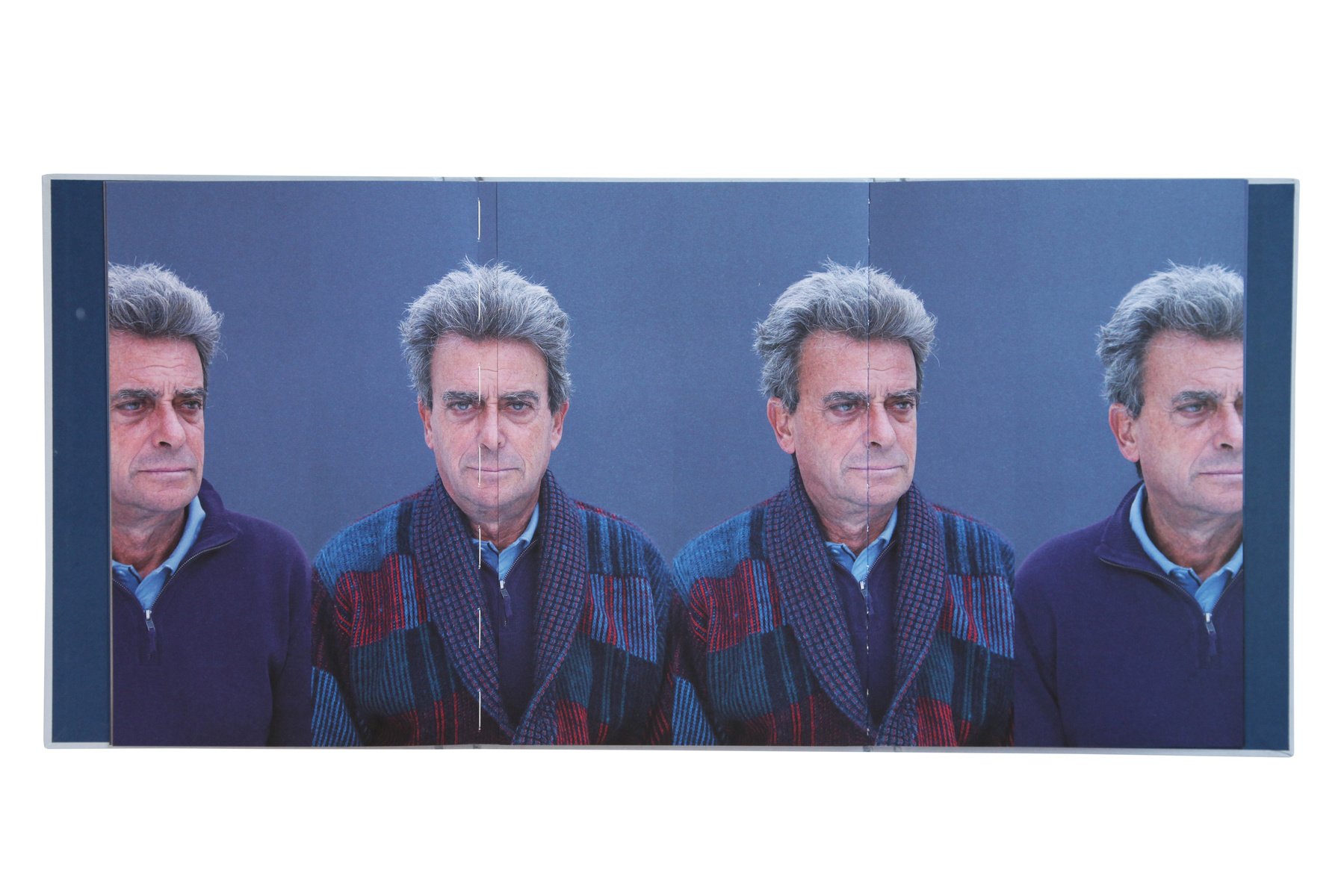

MS: I always refer to my project, Moisés, as an impossible search: an attempt to rebuild my father’s image through fragments of portraits of men his age had he still been alive. The project is born out of a syndrome my twin sister and I share in which, when one is unable to see the deceased body of a loved one, the grieving process is interrupted in the denial stage. I discovered it to be a syndrome many years after I began experiencing this, while researching this project. Since our father’s death, my sister and I have often experienced the feeling that we’ll run into him in the street, by chance, upon turning a corner.

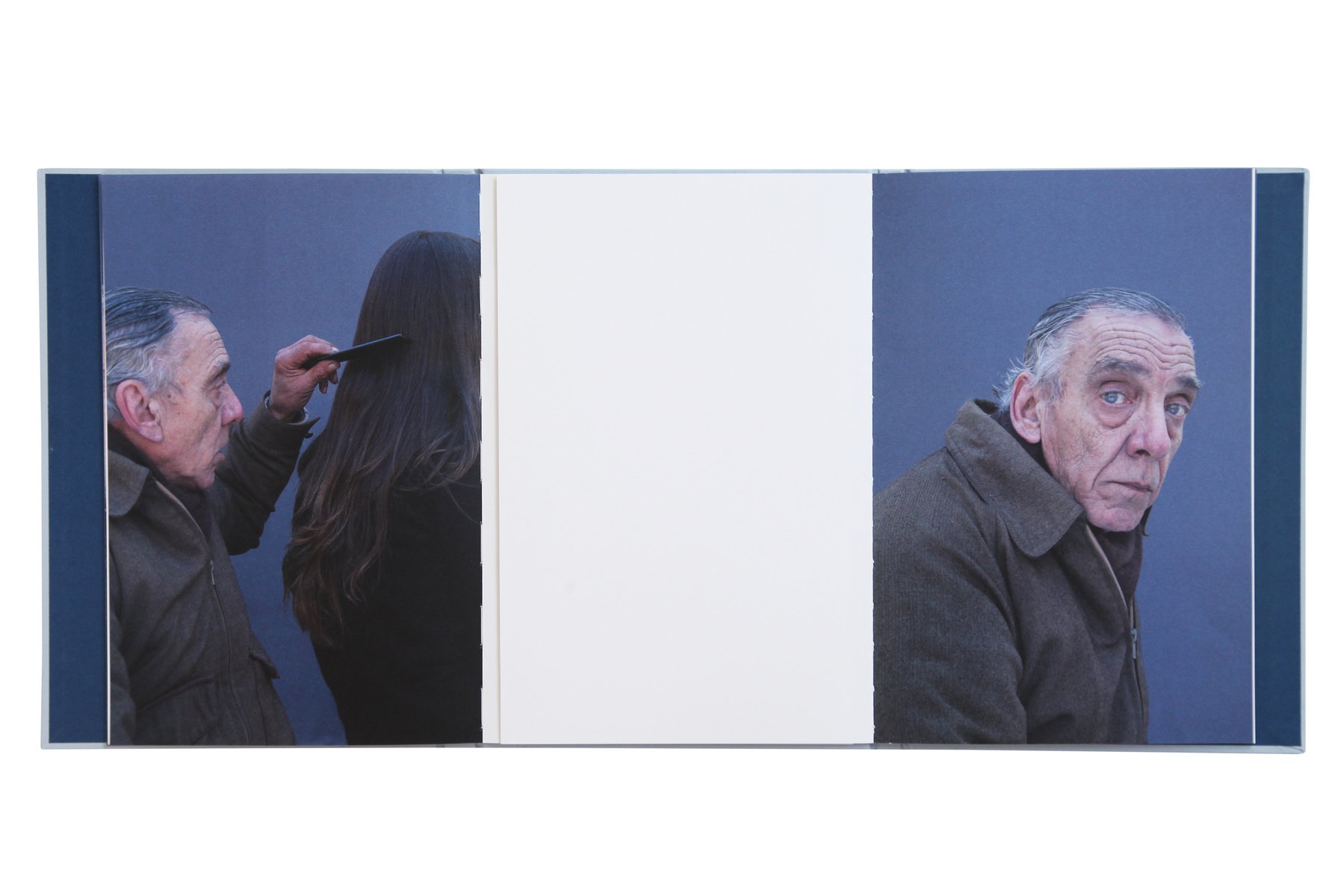

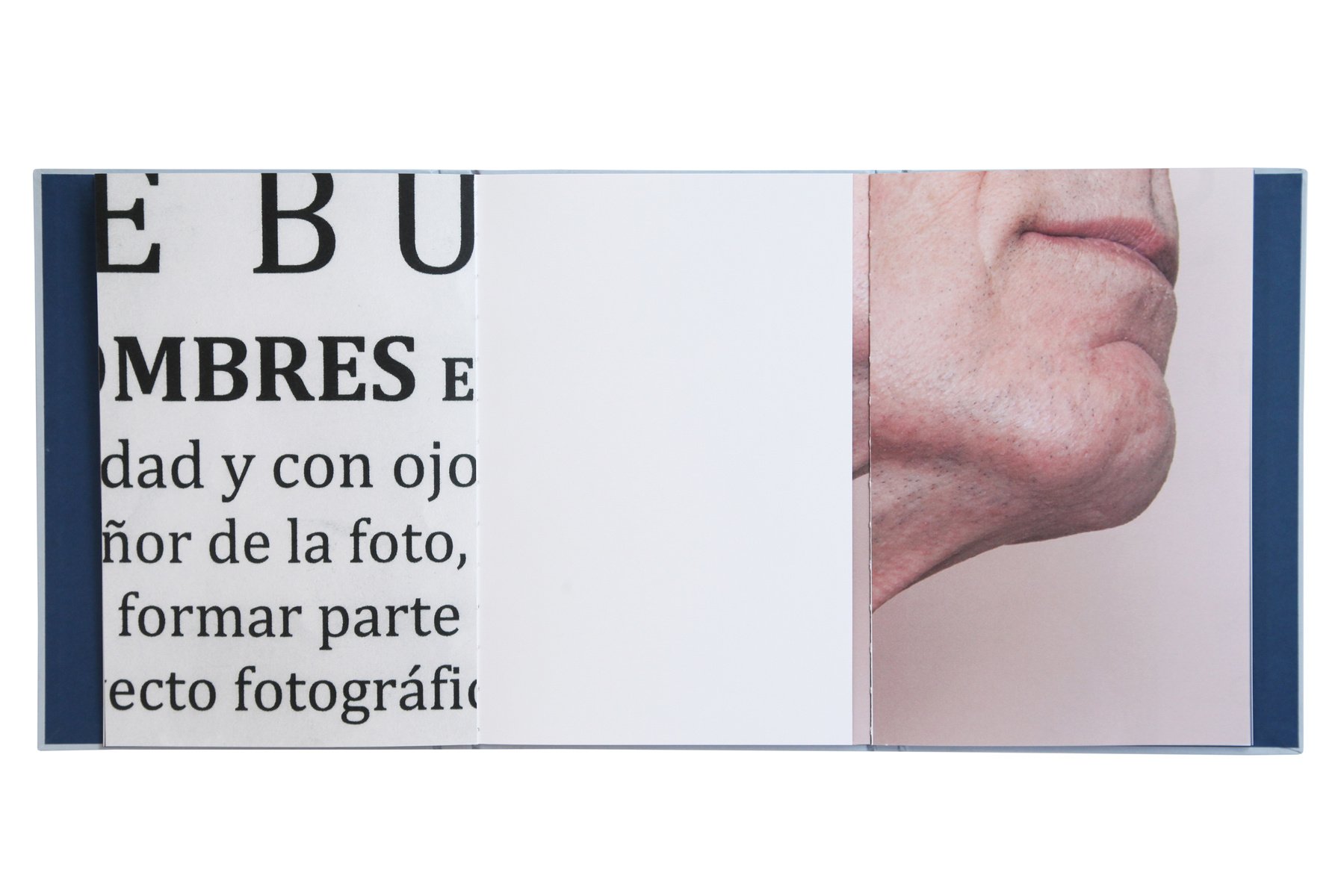

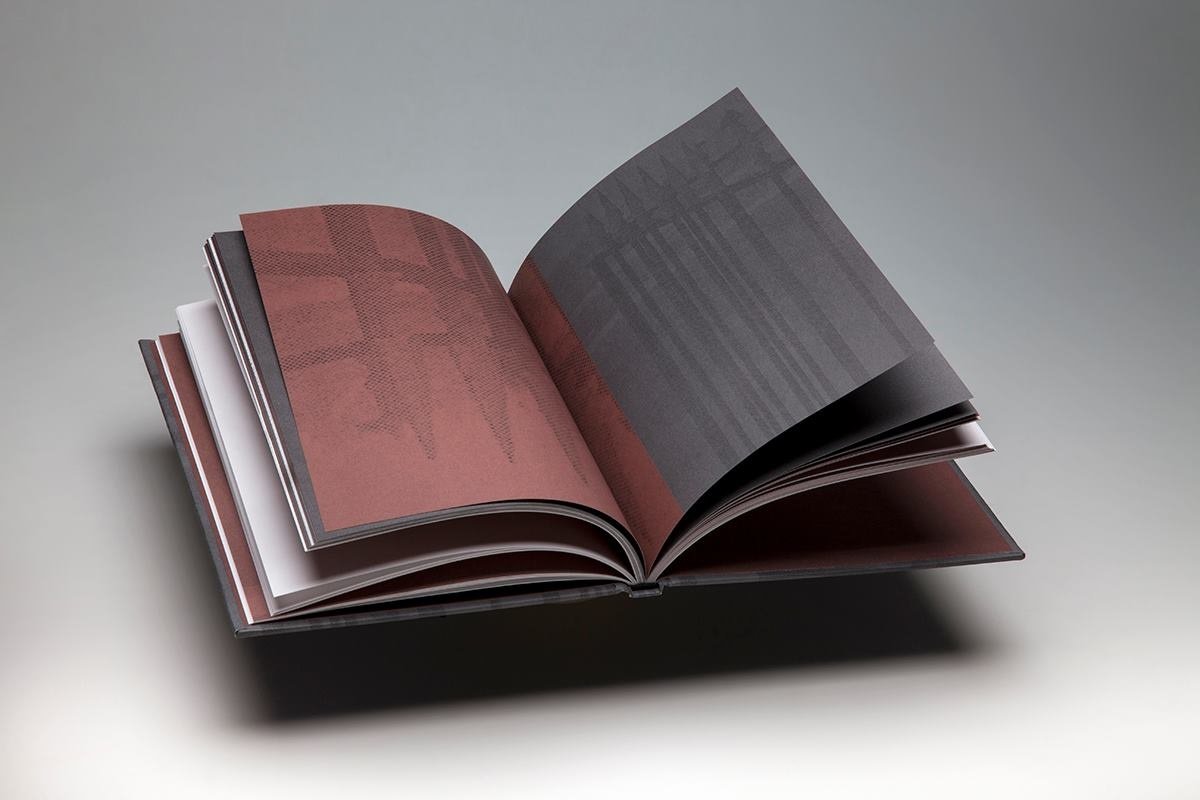

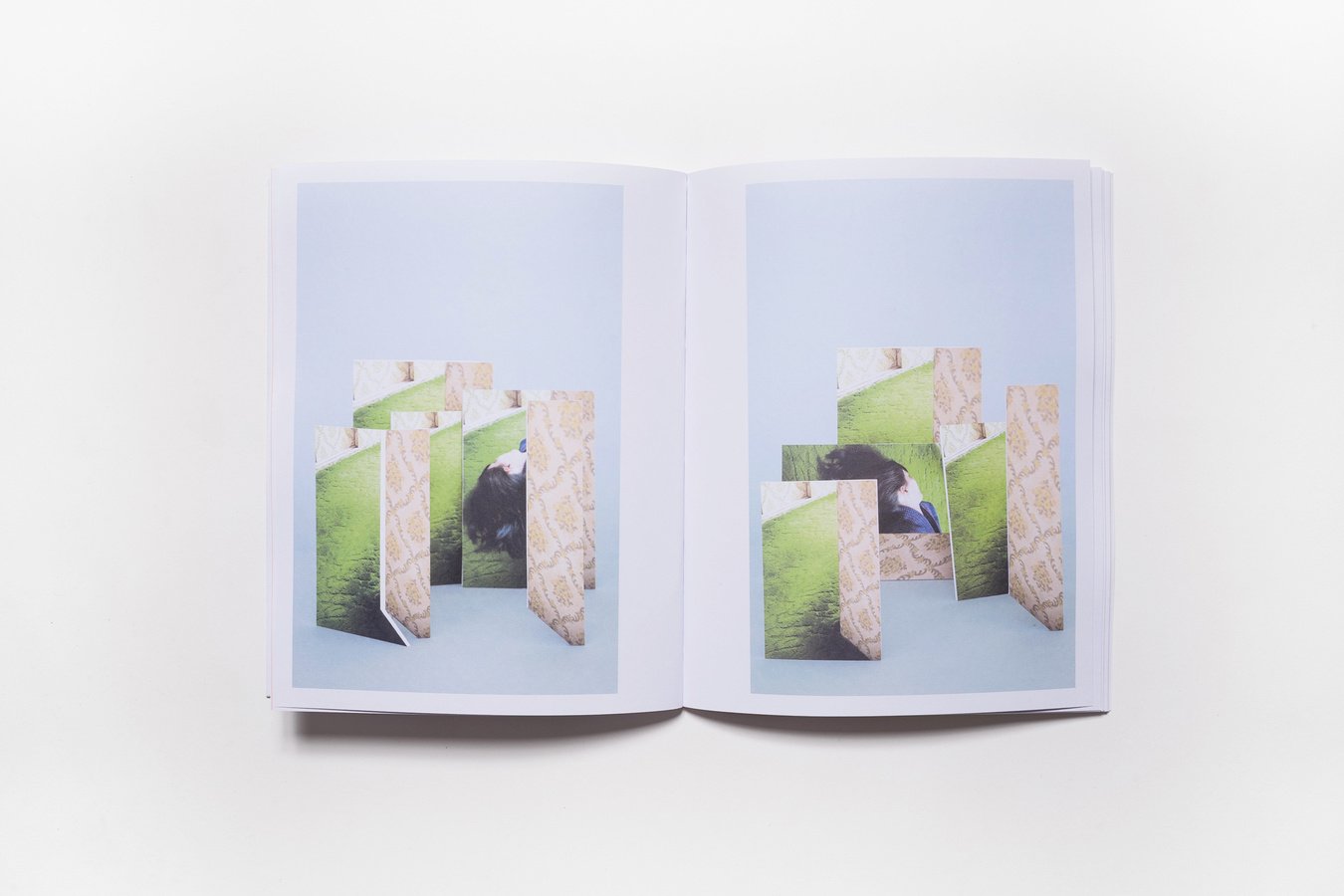

There are many ideas that appear in the Moisés book that, as you mentioned, continue to be a constant in my work. I’d say the idea of the book as an experience is the one that continues to shape my practice the most today. When I began working on the first book maquette for Moisés it was clear from the beginning that I wanted to the viewer to relate to my experience making the photographs. Most notably, the book’s architecture—the way the viewer turns the pages, staggered—mirrors my own search for my father’s impossible image. Turning one page from one side, then from another, successively, immerses the viewer into a feeling of searching, revealing, and finding while at the same time they may lose themselves in the likeness of the portraits of these men in the book.

Since this first publication, I have been interested in exploring the potential of the reading process as the moment/space in which meaning is created.

RS: Your book Mr. & Dr. is essentially an intervention on an existing archive or narrative. What attracts you to the possibilities of revisiting an existing story or material repository?

MS: I’ve always believed in adaptations, revisitations, rereading, and versions as a space for potential narratives. Both my partner—who is a writer and co-author of this book—and I are interested in the notion of “intertextuality”: how our work is informed by infinite references we hold and encounter.

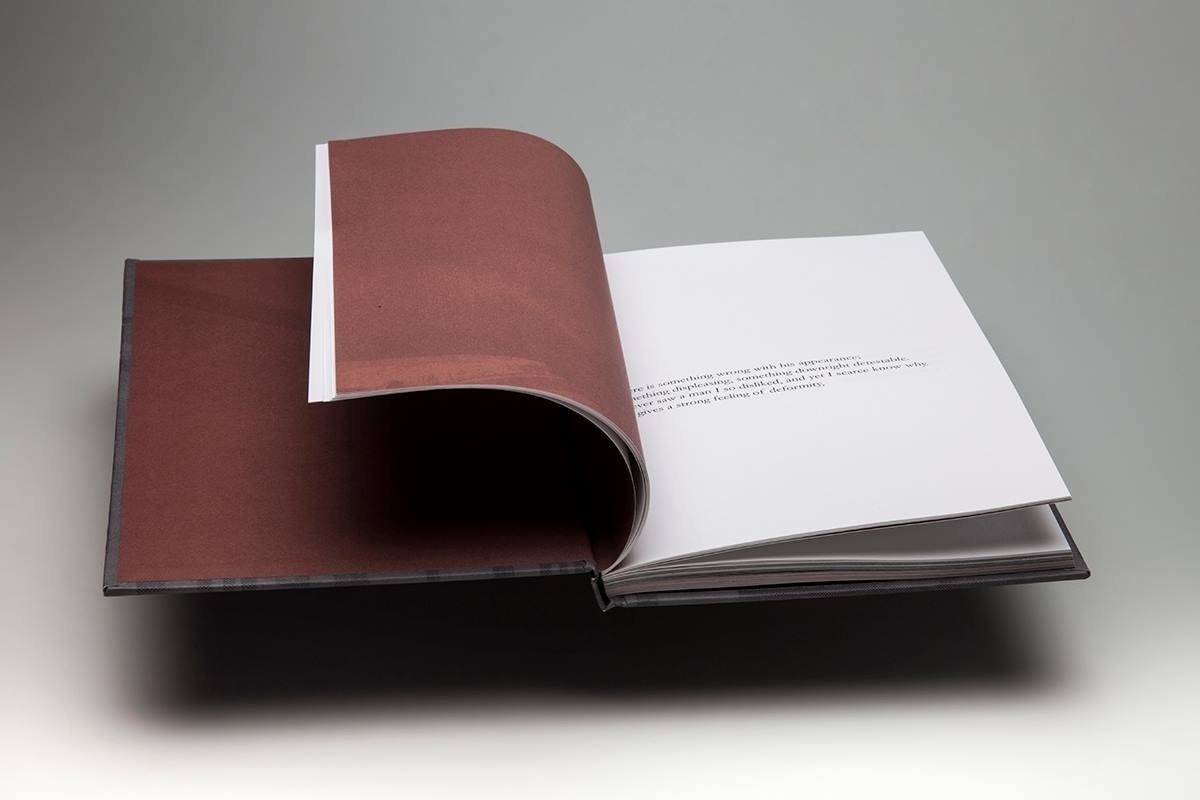

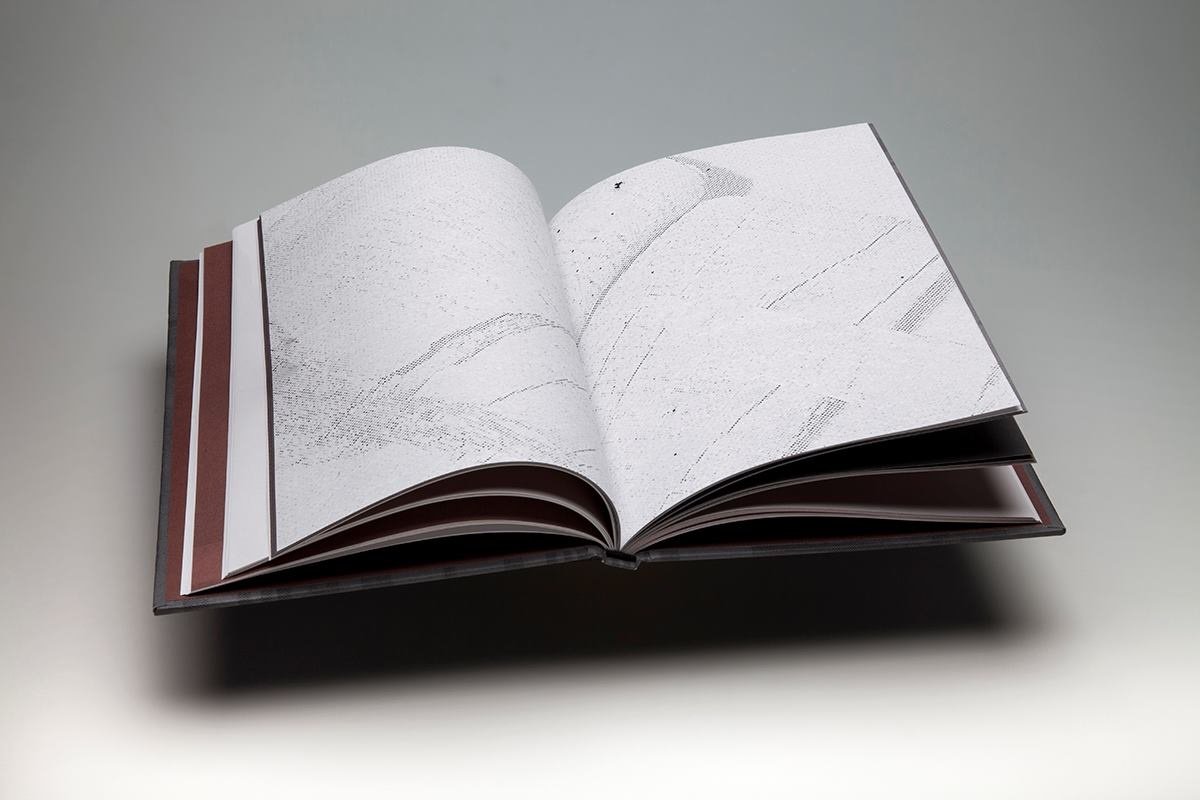

We decided to take on this adaptation of The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson from the fear of the unknown, of that which we do not understand, instead of through the lens of the binary that inhabits every person—which is also the lens through which this novel is most commonly analyzed.

He worked with the original English text and adapted the first part to narrative poetry. The second part, Dr. Jekyll’s confession, is also edited primarily in length. I worked with images from my archive to create collages which I then intervened with a process of “degradation,” attempting to transform them into more graphic—rather than photographic—works. With these elements, paired with the absence of a traditional narrative structure—unlike Stevenson’s story, we decided against protagonists—we attempted to break or displace the hierarchy that is generally established between image and text, in which the text tends to anchor specific meaning for each photograph. Through the repetition, fragmentation, the impossibility of clearly describing what the images depict, our aim was to create an atmosphere that would evolve and accompany the reading.

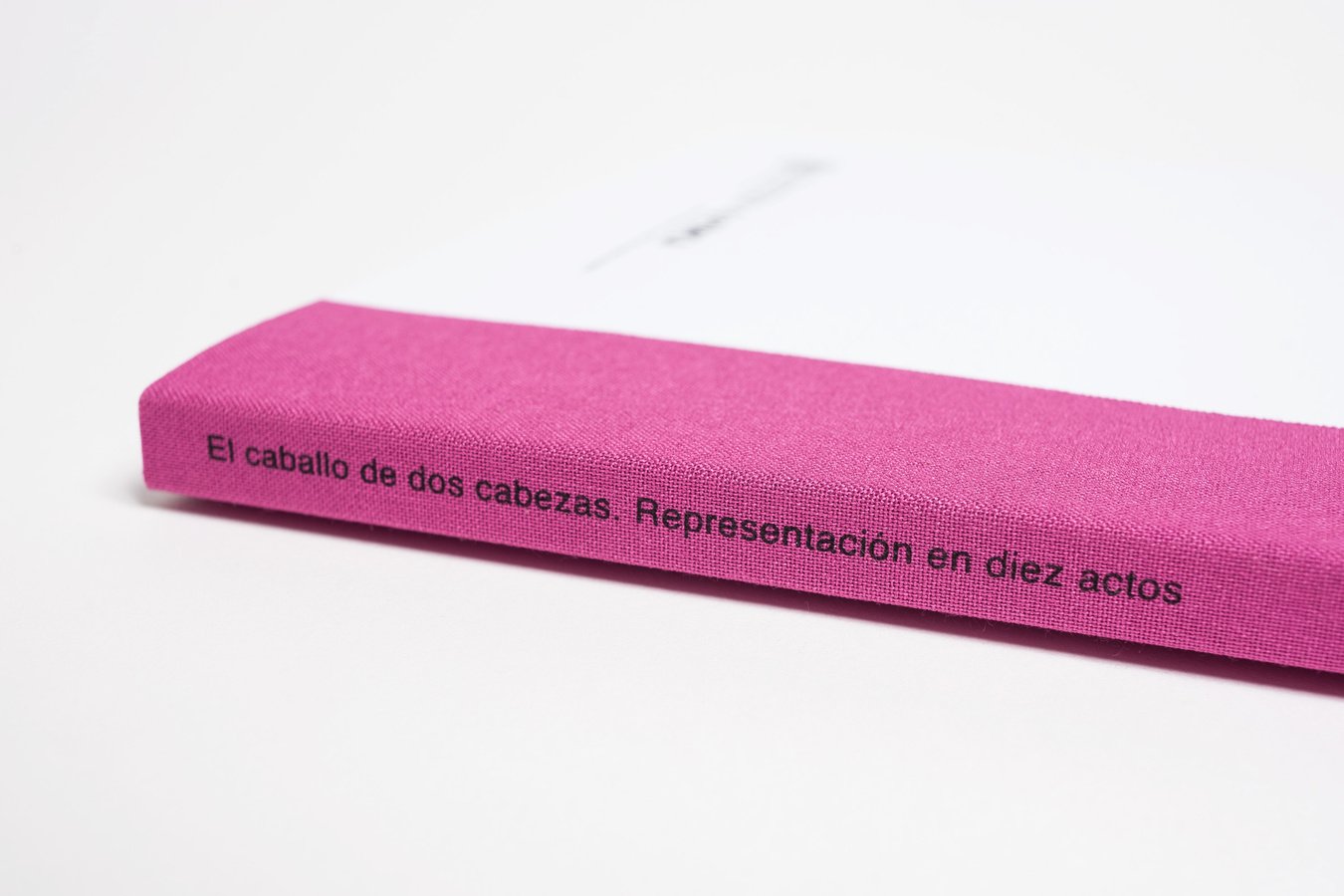

RS: I want to spend some time with your most recent work, The two headed horse, which is also a book titled The two headed horse. Reenactment in ten acts. First I’m interested in your relationship to the book as an object. Books are one of the primary ways in which narratives have been disseminated throughout history, and remain a symbol of the most traditional and enduring record of the world’s tales. As you aim to disrupt the way we relate to traditional notions of narrative, memory, and storytelling, why is the book the right form for your work and what’s your particular relationship to that medium.

MS: In this work in particular—a recreation of photographs from my series The two headed horse (self-portraits with my twin sister)—the concept for the book existed even before the series of photographic recreations did. This led me to think of it as a book-device that functions as a sort of script to bring a performance to life. That is, that the book becomes the work itself when it is activated, when it is materialized through its embodiment.

I’m interested in rethinking the status of the book as a material object, and as such, the notions of finality, fixity, and stability that are often adhered to it. Often books are considered the conclusion of a process, the last link in a long chain that begins with a photographic series, which are then exhibited, and finally land on the page of a book. The two headed horse. Reenactment in ten acts operates as a moment in that process, not as a finite ending. It enables a passage, a space for exploring the transition of a fixed image into a performed one. Through this performance, the images are formed (given shape), and alongside the book they open up to new meanings.

RS: Can you give us an overview of The two headed horse. Reenactment in ten acts? It’s a layered and complex project, please share a bit of the conceptual ideas behind this work, and some of the practical elements that you executed and which we see in the book.

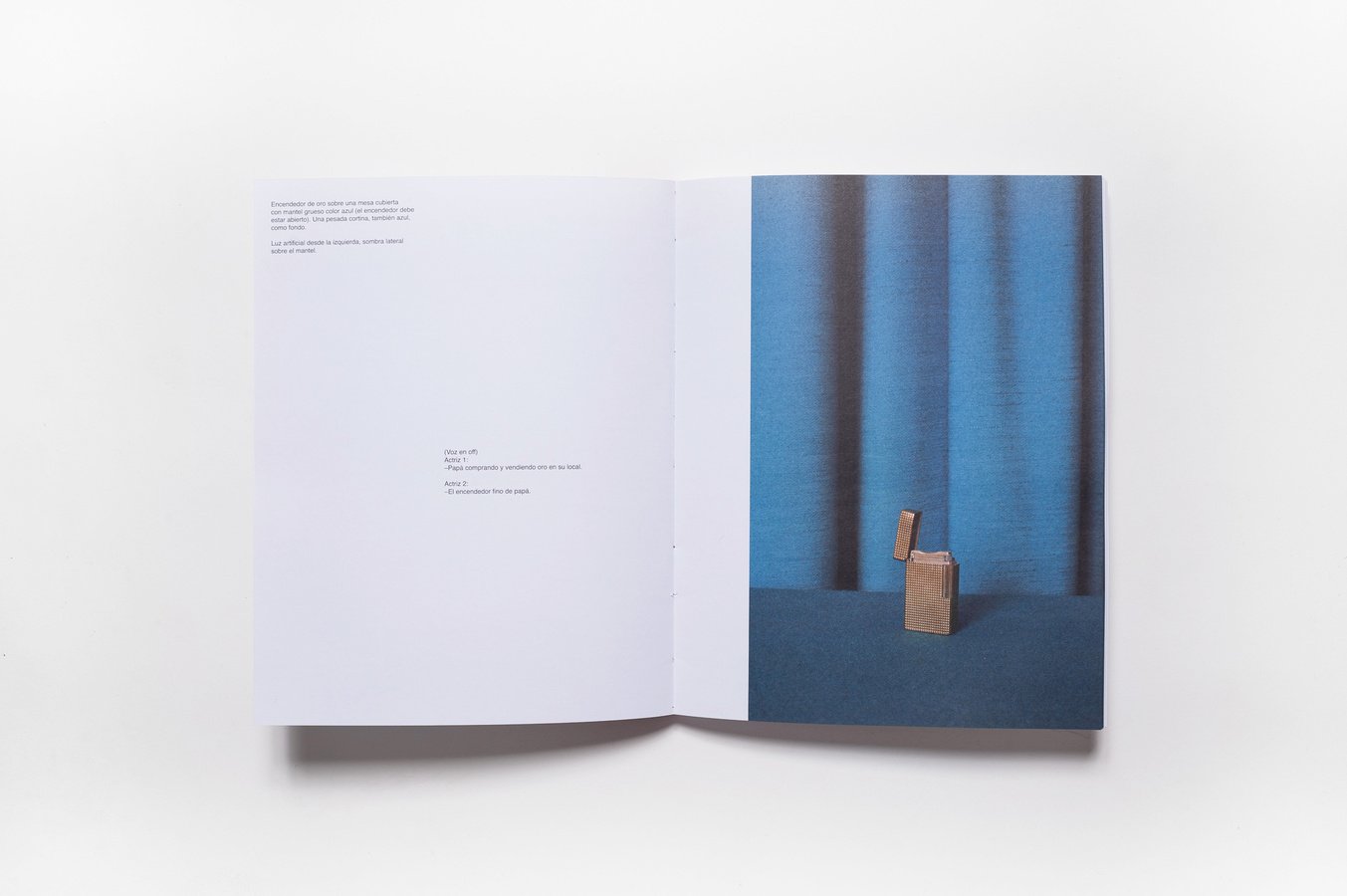

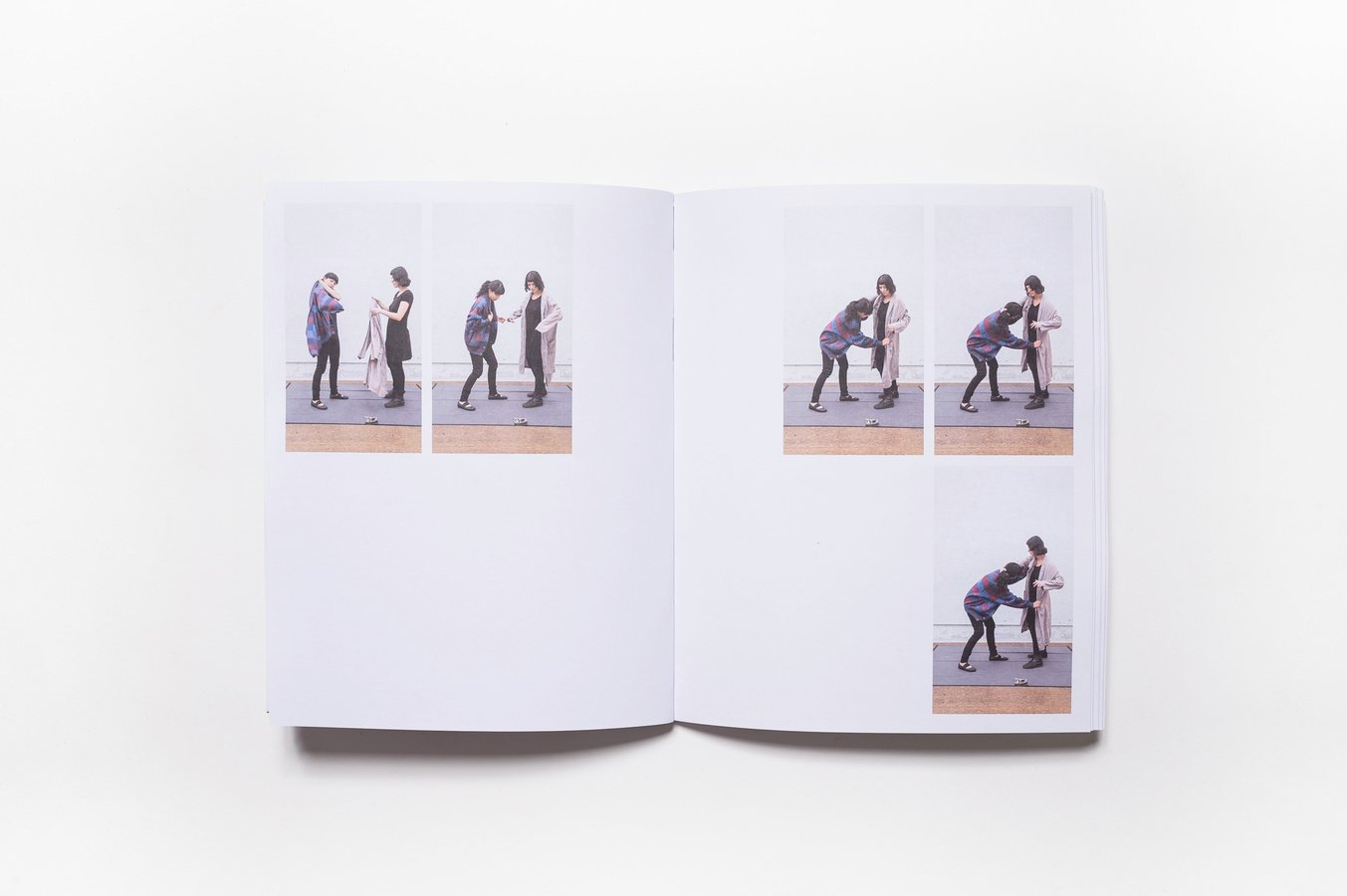

MS: This project re-signifies photographs from a series titled The two headed horse—which consisted of self-portraits with my twin sister that revolve around memory and fiction. Conceived as a performance, the reenactments explore the power of the body to dismantle meanings given to images, and to analyze the different ways we can read them once they are activated through the body.

With this idea in mind, I invited amateur performers to “embody” my photographs. In these sessions, I captured video and photographs of the performers’ representations of my original photographs. The resulting images are what appears in the book.

The final part of the process was the writing of the different texts that appear in the book—dialogues, notes for the performers, and technical annotations related to each scene. All the texts carry the same typographic treatment, without hierarchies on a visual level, with the intent to allow the texts to become affected through the embodiments themselves rather than by their visual treatment on the page.

RS: In Andrea Soto Calderón’s essay, she points out that “pondering other ways of making images beyond the representative regime is not the same as saying that images should renounce representation. It is not a question of no longer using representation. […] The challenge is rather to release the hold on the logics of representation […] in order to start examining the potential of images to articulate dissident modes of imagination, unexpected modes of gazing to see that which has never been seen.” I think imagination is a powerful tool for those navigating trauma, and world-building can be a meaningful exercise in understanding our own stories and the stories of the world around us. Imagination helps us put aside narratives rooted in binaries and normative constructs. Can you respond to this notion?

MS: I absolutely agree that imagination—and fiction—are powerful and necessary tools to articulate new narratives, to inhabit and shed light on experiences outside of binary and hegemonic norms. Ursula K. Le Guin reminds us that the imagination is the singular most useful tool that humanity possesses.

I also think that, in relation to images, the work of imagination should be aimed at destabilizing the traditional functions that have been assigned to photographs, and to introduce new logics that enable impermanence, the provisional, the transitory, the ephemeral.

RS: Lastly, you’re currently in Barcelona completing an artist residency. What can you tell us about your work there? Anything you’re able to share?

MS: I’m continuing my work in relation to the performativity of images, and the body as a way to break down or disturb narrative frameworks long-assumed as unique. This is a field I am exploring slowly, with my arms outstretched and with a hesitant step, but I’m trying to enjoy not walking in a straight line.

RS: Thank you Mariela, a pleasure chatting with you.

MS: My pleasure!