Q&A: Kyle Vu-Dunn

By Rafael Soldi | November 9, 2017

Kyle Vu-Dunn (b. 1990, Livonia, MI) studied Interdisciplinary Sculpture at The Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) between 2008 and 2012. He has exhibited work in Los Angeles, Dallas, Baltimore, and New York City, with an upcoming solo show in Chicago in April 2018. He currently lives and works in New York City, where his solo show Leaves Don't Thank the Sun continues at Sardine Gallery until November 12, 2017.

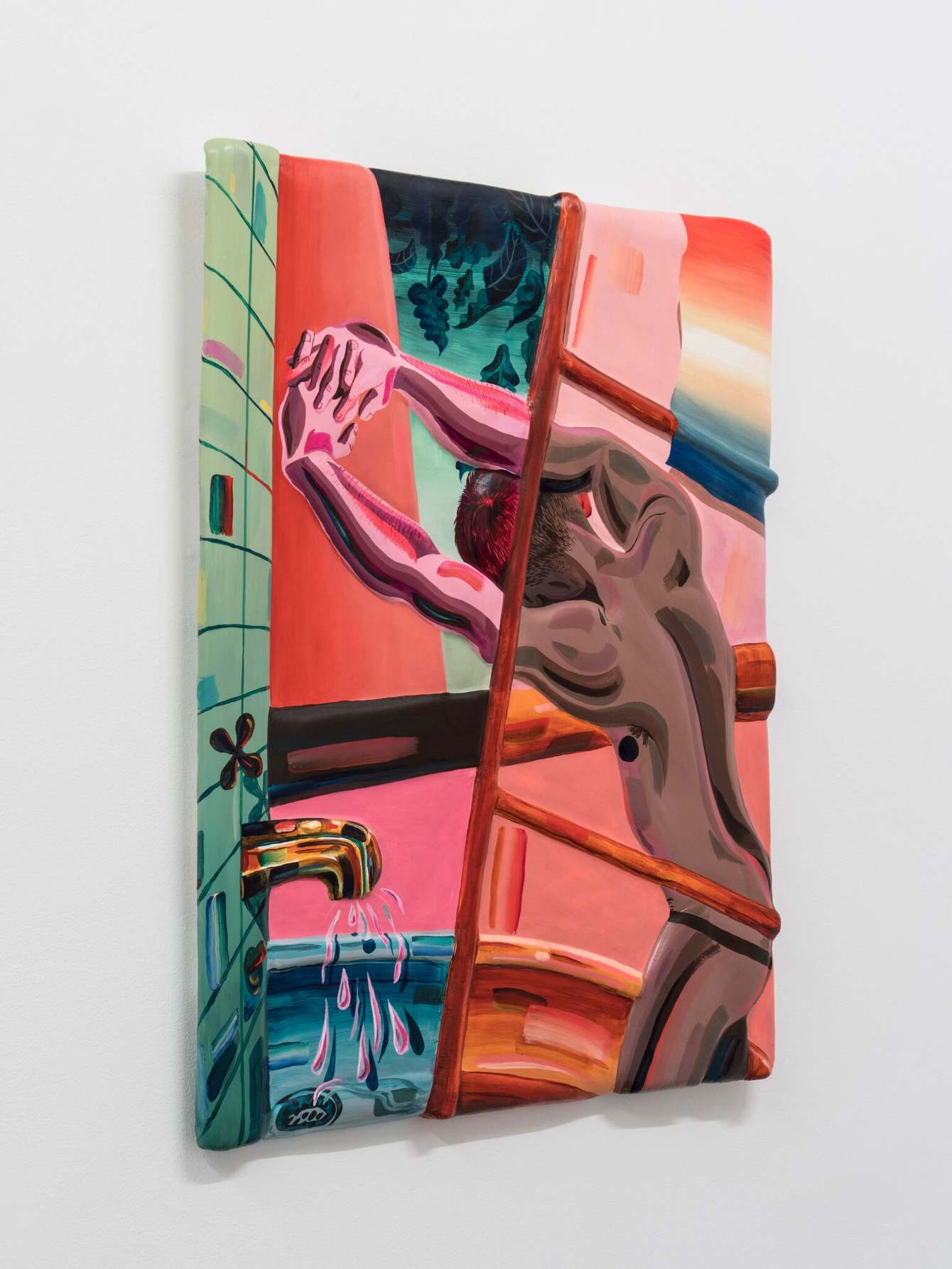

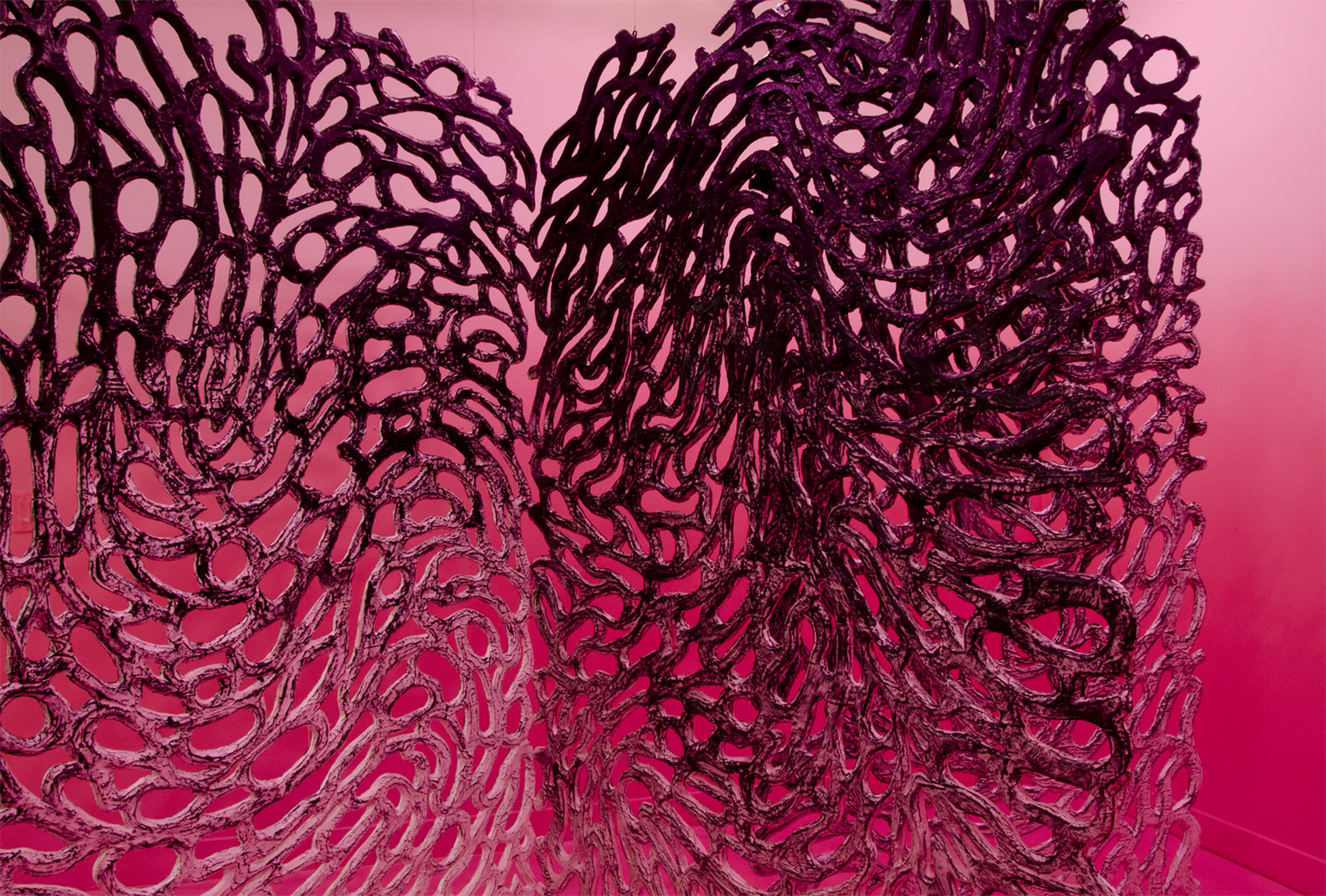

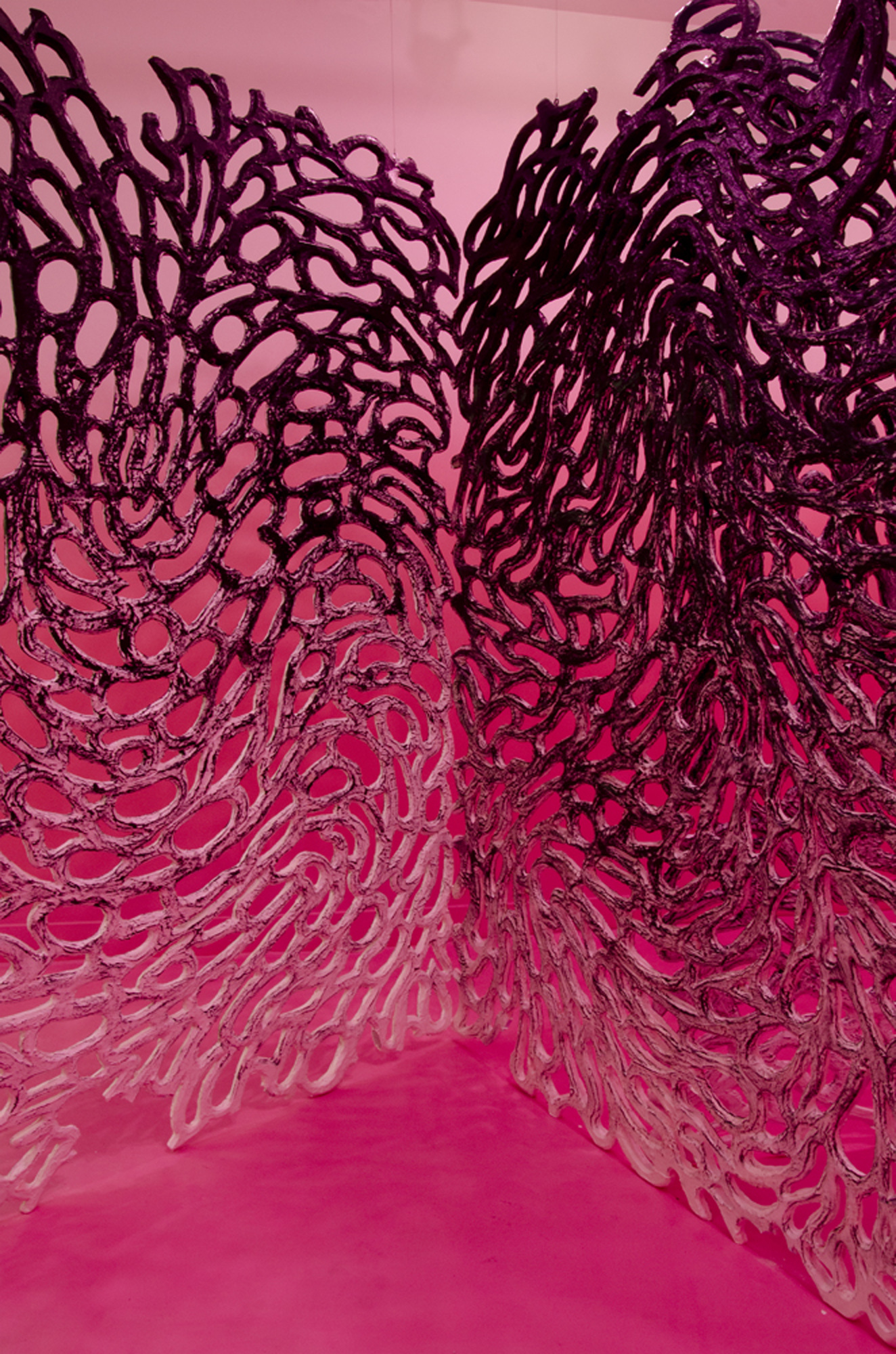

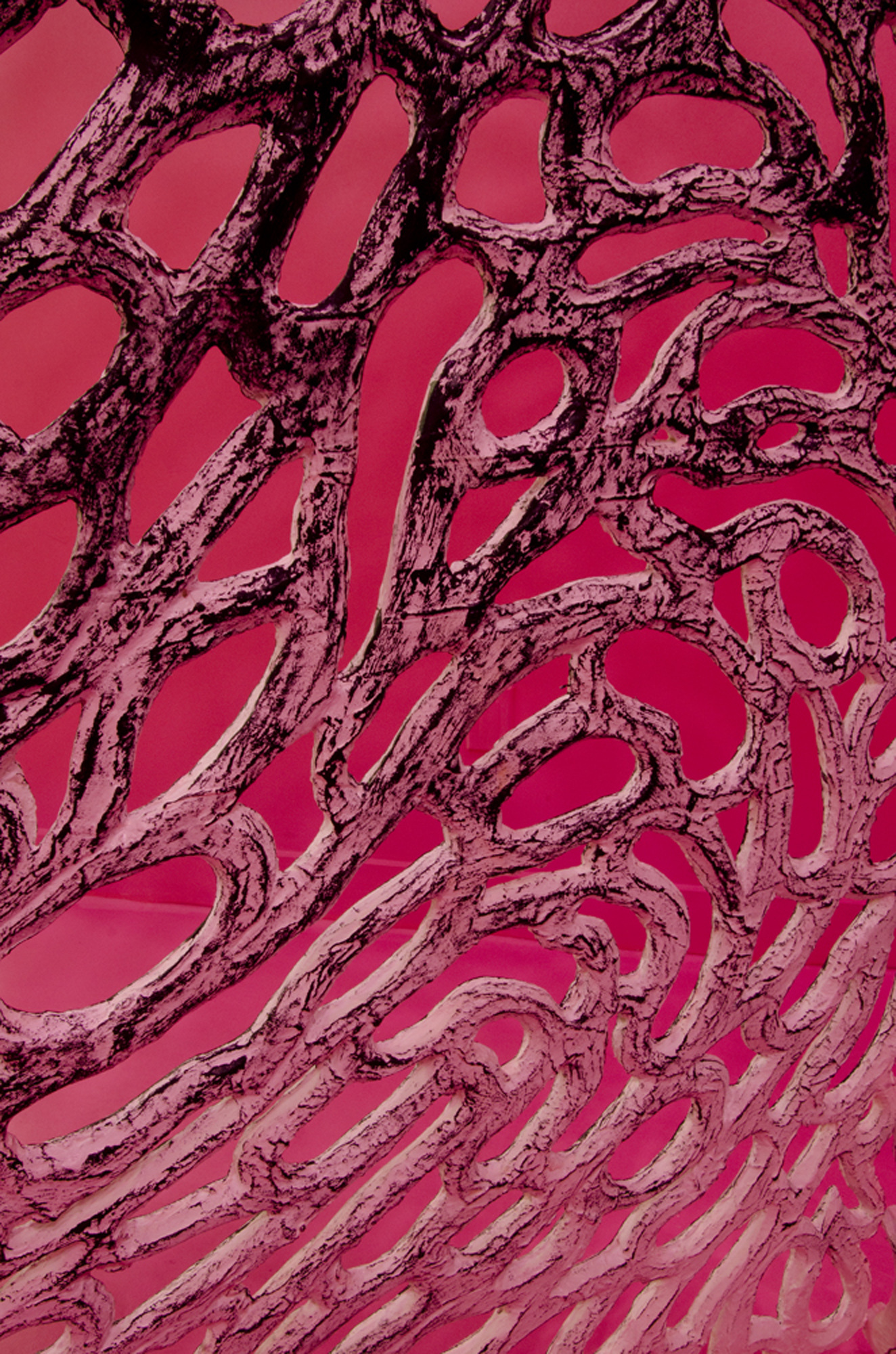

Installation of Leaves Don't Thank the Sun at Sardine

Rafael Soldi: Let's talk about the evolution of your process. As you've experimented and perfected the formal elements of your work, how has your process changed and evolved?

Kyle Vu-Dunn: I used to assemble my reliefs from multiple carved parts and build the narrative of the work as I went. But as I’ve grown more confident in image making, I’ve changed gears and carve the whole relief from one block of foam. This takes planning, which I have achieved with more detailed studies before the carving work begins; I choose color to heighten the sensuality and emotion in the work, and these small paintings help me to pin down the specific character and composition of each before I begin.

As a sculptor-come-painter, making relief work, I had always balked at simply filling in canvas or paper. I enjoy the autonomy and further control over the image that the sculptural element provides—if it doesn’t have to be flat, why should it be? But these small studies have evolved into making traditional drawing and paintings on paper on the side, which is a productive way for me to quickly cycle through ideas that I can bring back to the more complex relief work.

Big Stretch in-progress documentation

RS: Do you work in project form, or do you see all of your work as being one thread? or both?

KVD: The evolution of the narrative element in my work has been one of greater specificity over time. My work from last year could be read more allegorically—as the figures and surrounding accouterments (vegetation, curtains, etc) floated on a lattice like structure, the elements of the composition were more isolated and read like stage props. In my new work, there are similar male figures but there is no negative

space, and the domestic/garden spaces they inhabit are more fully realized and specific.

These works recount my own experience as a queer man and the desires I have for the world we live in. Misplaced masculinity does so much harm in the world, and boys are taught at a young age to police themselves and their peers to not show emotion or vulnerability, to not be sensual. A friend posted an incredible essay recounting this phenomenon called “The Legion Lonely” by Stephen Thomas. It describes the rise of loneliness in men as a direct result of their socialization as boys, namely that they are taught to not build a support network or trust their own need for other people, other men and women, for physical and emotional comfort. I think any images we can make of men allowing themselves to be soft is important.

Formally speaking, there are of course recurring elements whose novelty is exciting when you first discover them; you use them in various fashions throughout the work, and eventually cycle them out. I’ve currently been making ribbons of refracted rainbow gradients in this way—both as a reference to gay imagery, as well as the emotional state of the figures. I picture intense high moon or noon when these light effects occur as a time of both action and rest that speaks to the way the figures are both languid yet confident.

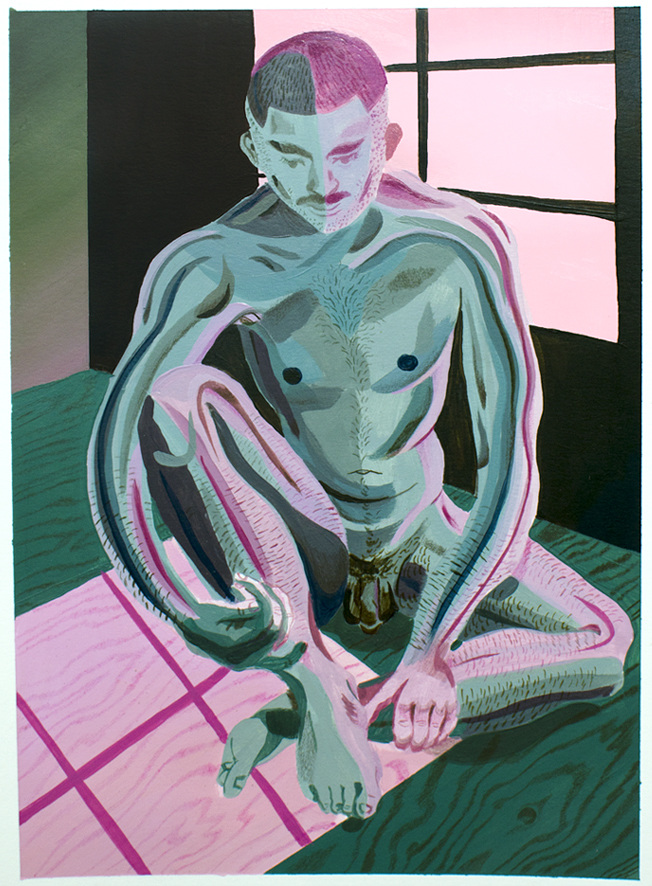

A Nail in a Cherry Pit, 2016

RS: Using the male bodies in a tableau coded with desire is a technique that has been around for ages, except now we have the freedom to make these performances more explicit. But we saw it in the work of Thomas Eakins, George Platt Lynes, George Tooker, Paul Cadmus, Duane Michals, etc. Do you ever look back to queer artists of the past and their coded language? If so, who resonates with you?

KVD: I would say Takato Yamamoto’s work has influenced me in this respect. The line quality in his work is exquisite, and there is a provocation in his mens’ gaze back at the viewer that radiates energy and electricity. There is a feeling of both haughtiness and a genuine smirk, something mischievous, in

his characters that I find fascinating. His work is often quite explicit, but coded language there is indeed—Saint Sebastian struck with arrows, heavy phallic flowers and compositions structured with windowpane like structures between viewer and subject that implies a certain voyeurism.

I also use found vintage gay photography as a source of inspiration. Occasionally a more beefcake-y kind of 1960s studio shot, but more often real candid photos that have a genuine sweetness about them. I find these simply through deep Google image searching.

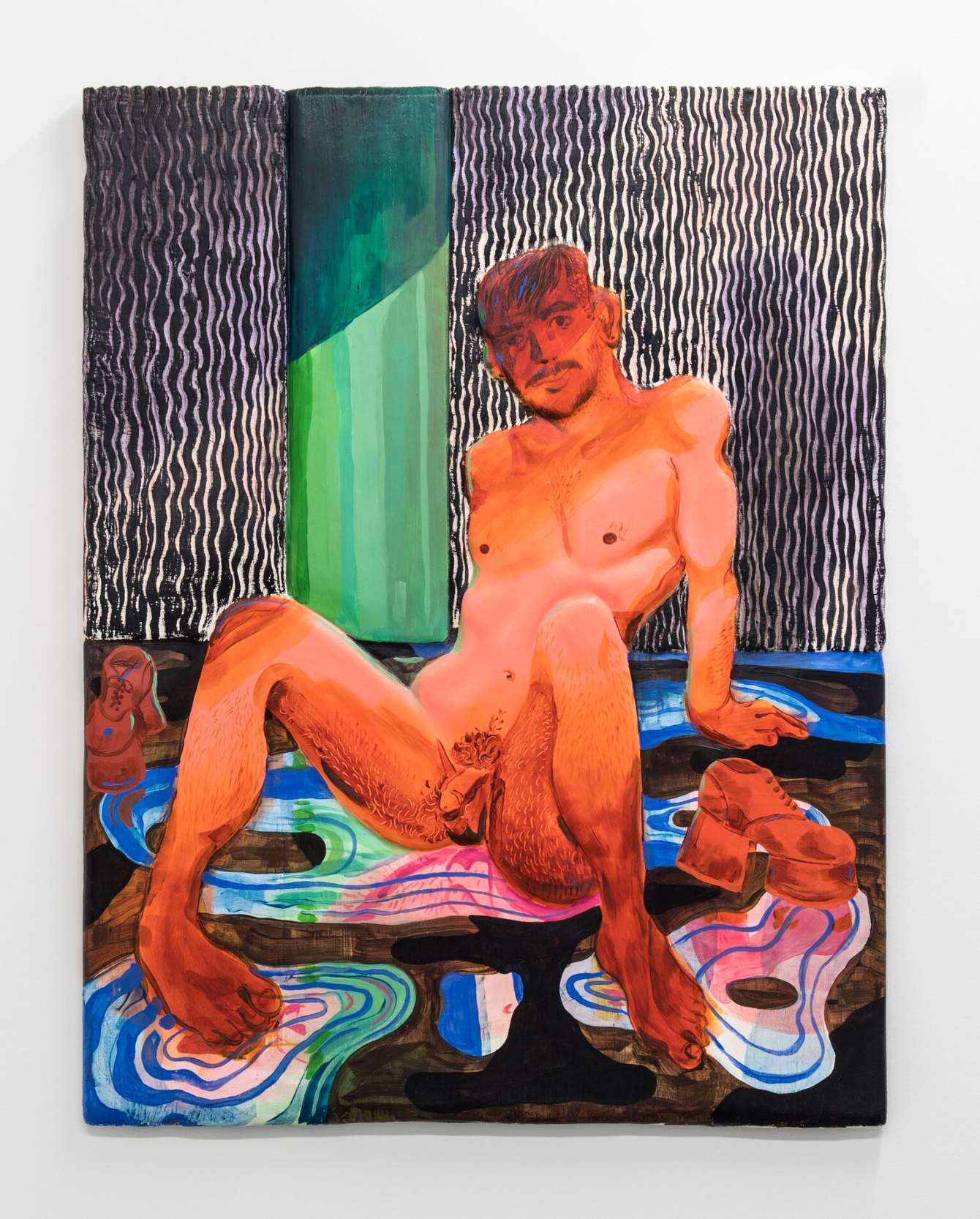

For Us Weeds, 2016

Foam, plaster, fiberglass, acrylic, gel media, lamé on panel 50 x 46 x 4

RS: One of the universal challenges of being a queer artist today is that the moment your work has a hint of queerness, it's not given an opportunity to be anything else but. How have you navigated this issue? Do you find that you have to fight for your work to exist in another context?

KVD: It is a struggle. I think we are reaching a critical mass at the moment in which queer imagery and culture-- and the contemporary vehicles of it such as magazines and TV shows—is reaching a wider audience than ever before. I used to have a more knee jerk reaction to being pigeon-holed, but now I feel like I just am going to make what I want to make and people can contextualize it as they wish.

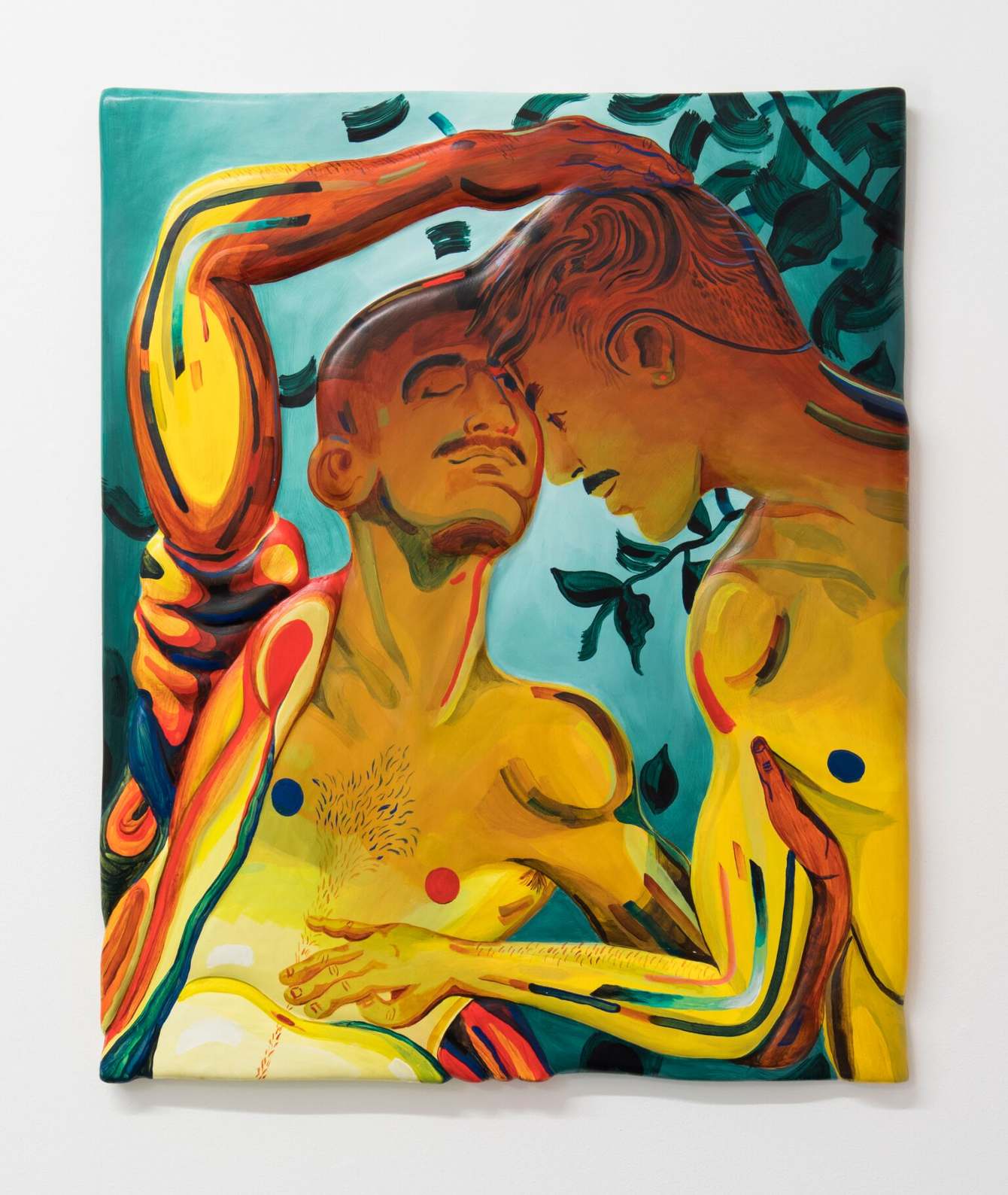

Blue Crush, 2017

Acrylic and crayon on fiberglass and plaster reinforced foam

35.5 x 31 x 1"

RS: What role has Instagram played in the development of your practice?

KVD: I think Instagram is a great leveling force in the art world. But it is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it cuts out the middle man between you and your audience, and maybe renders moot old institutional models: you have to have an MFA for people to notice you, you have to work at such and

such a place, etc. But on the other hand, it also has increased people’s appetites for new content, and can sometimes feel like an exhausting cycle where you are trying to entertain your followers rather than produce good work. It also de-incentivizes risk taking, as people may come to expect a certain “product” or “image” from you. That being said, I have gotten a lot of professional opportunities from it, and like everything, is probably best used in moderation haha.

RS: What are you obsessed with right now?

KVD: I am currently obsessed music-wise with the album The Red Shoes by Kate Bush; the last great book I read was Parable of the Talents by Octavia E. Butler; and I’m a little late to the party, but Kiki’s Greek restaurant in the Lower East Side in NYC is the last great restaurant I’ve been to.

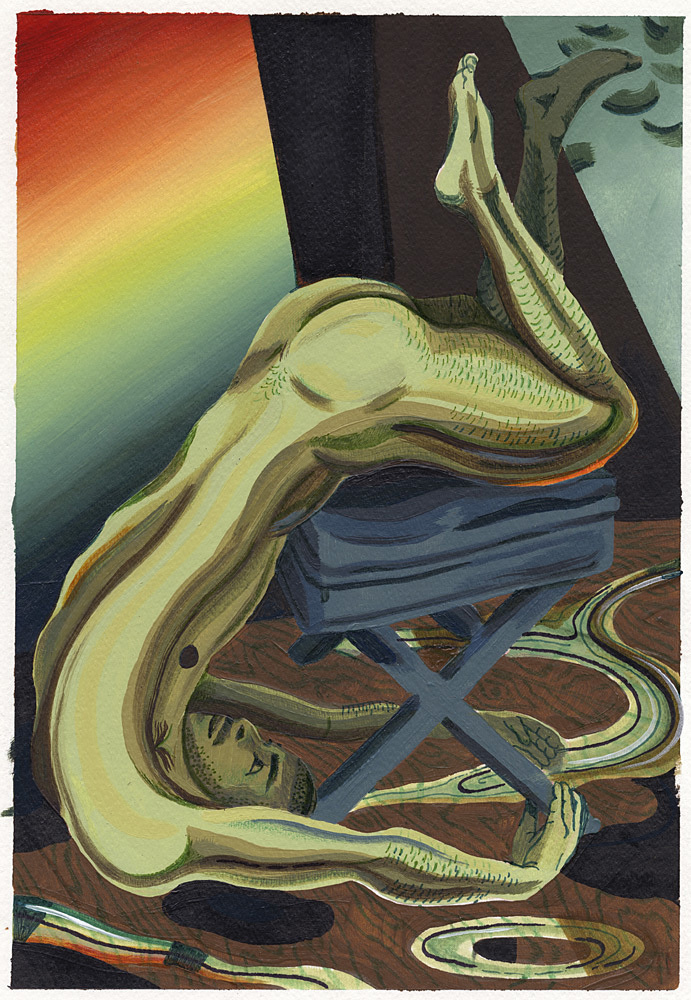

David's World, 2017

Acrylic, crayon, and pencil on paper 13.25 x 9.75"