Feature: Kottie Gaydos

By Rafael Soldi | Published August 10, 2017

Kottie Gaydos is an interdisciplinary artist from Rochester, Michigan. She holds a Master of Fine Arts from the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, MI and a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, MD. Gaydos’s work is held in private and public collections in the U.S. and China, most notably, the Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, MI. Gaydos serves as the Director of Operations, Curator, and Editor-in-Chief of Special Publications at the Detroit Center for Contemporary Photography (DCCP). Additionally, she is an adjunct professor at Towson University and the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, MD, where she lives and works.

Rafael Soldi: The moment we graduate from college is essentially the beginning of an artist's career. For you it was an unusual start—tell us about that adventure and the resulting work, From Awake to Awake.

Kottie Gaydos: At the time of my graduation from MICA I was awarded the Meyer Travel Fellowship, a grant which funds the making of a substantial photographic project and provides a solo show for the recipient after one year. At the time, I was distinctly aware that the award postposed the usual post-collegiate panic; I didn’t have to worry about what to do next. At the outset I never would have guessed that this project would become my sole focus for the next three years.

From Awake to Awake is the product of my time spent in the Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture with a family of Khampa Tibetan Nomads. I went with the intention to follow the story of Gesar, an 11th century enlightened warrior king, of whom the Khampas are said to descend, but found myself so enamored with the place and people of this small clan that I deserted my plans and stayed with one family the whole time. The Genong clan moves three times a year. They spend the summer months high up in a grassland pasture called Dashika. In the spring and fall, transitional moves take place between Dashika and Gerte, a valley pasture with stone homes that are a manageable distance from the nearest town. Most of my days were spent in Dashika, helping when needed, watching the kids, and being in the presence of the mountain, Mjera. I spent the first year traveling on horseback, going from small summer festivals at the highest points in the region, to following a film set as they travelled the grasslands making a movie about Gesar. The next two years were much more fluid, I often stayed with a friend in town and helped manage her guesthouse and cafe. I learned how to fix electrical problems and cook for twenty people, how to run down a mountain fast in a lightning storm, how to speak without words, and how to fall in love with a place that is not my own.

From Awake to Awake became a reflection of those experiences, particularly of my love and affectation for the place.

From From Awake to Awake

RS: You approached this time/project with a lot of uncertainty. How did the project change over time, both over the three years, and now that it's had a life of its own?

KG: During my first few months there, I made interviews with a wide range of people about Gesar’s story, I photographed and recorded in a way that I felt was expected of a documentary project. I quickly realized, however, that I was not in control of my time in the region. This is a truth that any traveler will know intimately, but I also found that the Tibetans have their own pace and that I could not force people to adhere to my arbitrary timeline. Additionally, the Chinese government was in control of events and festivities in the region, many plans would be suddenly changed because the government had determined a festival should not be held. During that time the government was very wary of large groups of Tibetans gathering, and perhaps even more so of allowing western tourists to be present at such events. During the Dalai Lama’s birthday one year I had to make an unexpected trip to the grasslands because the police had announced that all foreigners must leave the area. The grasslands were out of their reach, and so I got on the back of a motorcycle and left town to wait it our. This is all to say that I quickly let go of any structured schedule.

From From Awake to Awake

I also realized that projects evolve and grow from the original impetus to make them. As a young art student, the turn around time for work is likely a few weeks at the most. When you are able to give the work time and space to shift and become something which was not planned, it is a far more fruitful process.

Halfway through this project, a local monk and my former translator, was killed. It was a tragic death and I found myself at the edges of the mourners and within the events more intimately than a stranger. The experience sunk into me and began to shape the work into what I now see as a record of life in a rugged landscape. In retrospect, I see, too, that this is where vulnerability and the interest in the sacred and ritual came into my work.

RS: A challenge you faced was the responsibility of entering a place to which you were a stranger and finding a story to tell without fetishizing or appropriating the stories of those there. How did you balance this issue?

KG: I think the place and my time there provided the solution for me. Living in the grasslands, out that far in the elements, can leave you feeling raw and vulnerable if you are not raised in it. On my first day in Dashika an ill yak wandered into the compound of tents and died there. The men were all away on a trek and so I helped the women drag the corpse away. That same trip, lightening struck a tent a few miles away, killing an elderly woman and some of the yak herd. Out of the context of the time and place these things sound dramatic, even to me, but in the middle of it I just took it in. I noticed, slowly, that I had become comfortable seeing animals that had died from starvation or disease when I would go on walks around the mountains and hills, but the sudden death of the monk really shook me. It was then that I realized the place had moved so deeply into my being that my vulnerability must become part of the work.

I would go back to the States and process and view the film and review my journal entries. After this second trip, I noticed that the images had changed. I had used a Mamiya RB-67 on this second trip, making many photographs with the 11 pound studio camera handheld. It seems a bit silly now, but the work was much more magical because of it. The images blurred and were suddenly removed from a concrete representation of a person or landscape. This meshed with my journal entries, which were often lucid and fragmentary, to create a work that felt honest to my time in the place and the time between the subjects and myself.

Journal entry, From Awake to Awake

RS: Talk to me about this idea of "thin places," how does it show up in your work?

KG: I love this phrase, and first heard it used by the late poet and theologian, John O’Donnohue. In a conversation with Krista Tippet he spoke of landscape and beauty in a way that resonated with my experiences of vast and quiet places. I think it must have been 2011 or 2012 when I first heard it so the Tibetan landscape would still have been very much with me, despite being back in the States. There is a mystery to certain places, whether from their vastness (like the ocean or Himalayas) or because of their history (like the forests of Lithuania or the fields of Gettysburg). The idea of “thin places” seems to satisfy two core themes in my work: nature and the sacred. I have a reverence for the quiet places in the world, and I am grateful to have had the opportunity visit many such places. Within them, I find a sacredness. Of course, I am not alone in this—and perhaps because of that, I am curious why we as humans seem to crave the sacred and the natural. I’m waxing on now, but at the close of the From Awake to Awake project, I was deeply affected by not being in that place, in a kind of mourning for the grasslands and the mountain. To cope, and perhaps to also cope with not having any further life plans set up, I began a three year attempt to get a Fulbright to Ireland. My research followed a similar path as it had with Gesar, and I was reading oral histories of Ireland. There is such a deep rooted commitment to the landscape in that country. There is a real sense that the land is embodied. There is also a belief, perhaps not as widely accepted in modern times, that there are places where the veil between this world and the world of magic and darkness is thin. That, I believe, is where “thin places” truly comes from. I was thinking a lot about the veil between life and death, both from the previous work and from the loss of a loved one and so this idea sunk its heels in and stayed with me. I still think about it quite a lot.

From Notes on Loss

Essentially, I find the world a very romantic place, and one that is not at all what we allow ourselves to see in the day-to-day. I would like my work to touch that flame, even just a little. Though the work never quite gets there, each project is rooted in a kind of quest for those moments in which living is conflicted and places are charged. There is a book, by Keith Basso, titled Wisdom Sits in Places, this strikes that same nerve; the earth is our archive of energy. That can be taken as literally or as metaphorically as one is comfortable with, but I believe there is something sacred in the watchful bystander. Thin places have become a metaphor for landscapes that have borne witness.

During one stay in the grasslands, I was walking within a rocky formation with a friend and she began to build a cairn for a friend that had died. At the time, I was familiar with the hiker’s use of cairns to mark the path, but this use of the stacked rocks, she told me, was a marker of one’s life. Unlike the cairn I had known, this was meant to fall down with time; as too, the passage of time would allow the builder to release her grip on the memory of the departed. I think I have always been interested in the way that we mark the places and lives that we leave, or that leave us, but my most recent work attempts to take this on more directly.

RS: There was a dramatic shift in your work recently, from figurative and straight photography to abstraction and installation. Did that shift catch you by surprise?

KG:The installation element certainly did! And, to be honest, I’m still grappling with how to manage it. In some respects this is only a reflection of more global trends in photography at the moment: that sudden re-realization that the photograph is an object after all and can take up three dimensional space. When I decided to pursue a graduate degree, I knew that I wanted to take my work back into the studio and create a practice that was more inward and experimental. What I find fascinating is that the work, though incredibly different both in appearance and in process, is an investigation into the same questions that I have been asking over and over: how do I visualize the experience of the body in relation to a place or into itself? And, how do I visualize that which is felt, but cannot be seen?

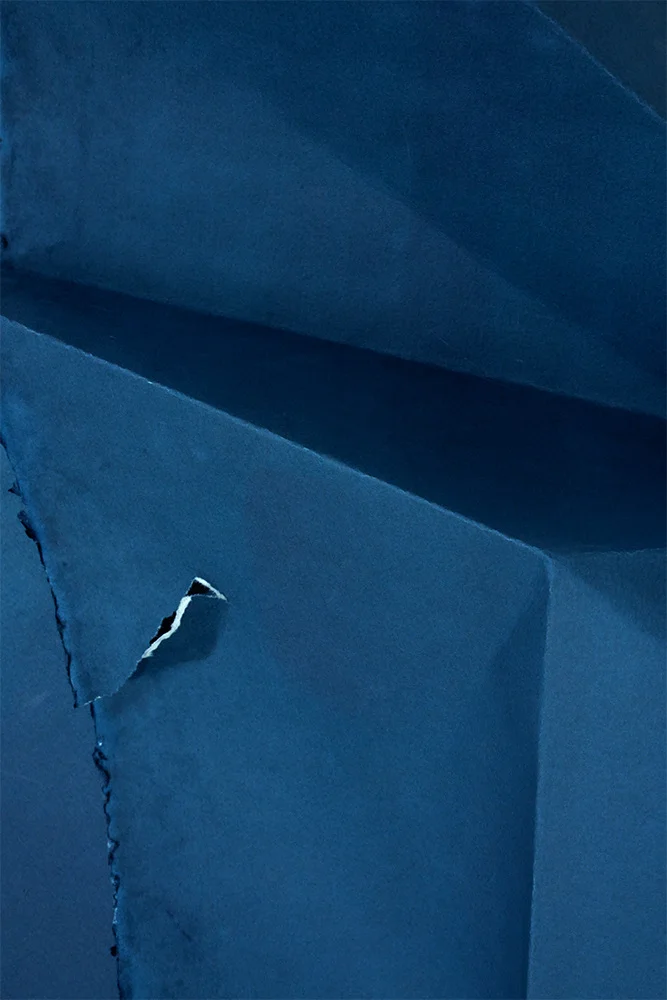

Unfixed, Fold No. 3, archival pigment print, in artist frame with unfixed cyanotype emulsion, 60x41in

Unfixed, Cairn No. 1, porcelain dipped in unfixed cyanotype emulsion, dimensions variable

RS: Your new work features large-scale photographs paired with fragile, totem-like stacks of ceramic vessels. These seem precarious and gallery staff are instructed to leave the scene as-is if the formation collapses and breaks. There are so many references here that are consistent with the poetics of your earlier work—questions of the body, of fragility and vulnerability, of loss. To that tension and impending uncertainty of collapse you then add the photograph, which is fixed in place and essentially a large swatch of blue, like an ocean, bringing a sense of symmetry and stability. There's even a contrast between the rectilinear tears and folds in the print and the organic clay forms, much like life and time are a backdrop for our own flawed, fragile bodies. Do any of these readings align with what you were thinking in making this work?

KG: Yes, definitely. It’s lovely to hear you read that in the work. In the early stages of the process I was struggling to keep the work separate from my experience within my body and my experiences of vulnerability. It seemed essential as a motivator for my interest in the work, though, and so I began to think about the experiences of my body in relation to my creative interests. I have always been aware of my body as something seperate from my experience of self in a way that I believe many cis-gendered people experience only in phases (such as an aging body or a body after motherhood). Though never in dire harm or ill, my body has been a subject of much emotional and medical attention. I was born with a cleft lip and palate and had many surgeries throughout the first 15 years of my life to work to repair it. As a college student, an autoimmune disorder caused my hair to fall out and my immune system to weaken. While neither of these experiences negatively impact the way I go about my life today, they have meant that I have been very aware of the workings of my body and the physicality of vulnerability from an early age.

From Unfixed

The work, I hope, lives in a space of duality that reflects my contentedness with my body’s challenges.

I simultaneously do not want the cairns to fall over and yet, if they break, they will become something new, and I would like to see what they become. Maybe, too, when the stacked vessels are in place the viewer will sense, as they approach, that there is something open and vulnerable to them; a thinness to their current success. The cairns are an attempt to make physical those spaces where in loosing something—something else is gained: to make the viewer aware or sense that something could be lost.

The field of blue, is very grounding. It is easy to get lost in blue; it satisfies both the sadness within the human experience and suggests the calm embrace of healing, like the ocean as you mention. The stacked vessels speak more directly to the temporal nature of our bodies, time and vulnerability are intrinsic to this. We are so deeply connected to our physical experience and selves, that I think this is often considered the greatest loss, but what happens when you ground that vulnerability in something much more open and vast? For me, that is where the rub is: the space between the two, our need for our bodies to go on forever in the “ideal” state, and for the emotional to not become too encompassing.

RS: What's next for you? What have you been up to lately?

KG: I have a residency coming up in the winter at the Vermont Studio Center where I will be as a sculptor—an concept which still baffles me, but one which will provide a lot of space to explore! I have been cataloguing shadows, recently, and am curious how to move forward with them in mind. The dissonance I just spoke of in the Unfixed work is something I would like to continue to explore. Junichiro Tanizaki wrote, in In Praise of Shadows, that “we find beauty not in the thing itself but in the pattern of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates… Were it not for shadows, there would be no beauty. I suspect that this will continue to be explored with paper. Paper is such a fascinating material: It scars like the body, one sheet may take on many different forms, it is fragile and has the capacity to contain multitudes.

From Unfixed

RS: Can you share with us something random, anything at all, that you've seen or noticed lately that inspired you or gave you a new perspective?

KG: I am learning Japanese, and am still in the early stages of grasping the structure of the language. In Japan, you often do not speak directly of something or of a person, you describe and allude to your subject and meaning. This is very poetic, but also a bit challenging at times—particularly for a new speaker! What I have found interesting in this is how American I am. I want to say exactly what is on my mind in the most direct way, and I find it difficult to heed the social expectations that require assumptions and suggestions in discourse. I love that this has made me realize how socially connected I am to America and how much we are each a product of the cultural and historical make-up of the places we are from.

All images © Kottie Gaydos