Q&A: kenneth guthrie

By Jess T. Dugan | August 1, 2019

Kenneth Guthrie (b. 1993) earned his MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago in 2019. He obtained his BFA in Studio Art with a Photography emphasis from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock in 2016. Guthrie’s work explores notions of personal identity and representations of queer people through performance-based photography and video projects. His images have been exhibited nationally at Colorado Photographic Arts Center (CPAC), LATITUDE | Chicago, Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts (MCLA), and have been published in Communication Arts, PDNedu, Photographers Forum, and The Magenta Foundation’s Top 100.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Kenneth! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today! Let’s go back to the beginning. How did you originally discover photography, and what was your path to getting to where you are today?

Kenneth Guthrie: Hi Jess! I am so excited to be speaking with you! Thank you for having me on Strange Fire. I first discovered photography when I was a student in junior high through fashion magazines like Vogue, Elle, and Paper. My father passed away when I was a young child, and growing up with that trauma was hard because I didn’t really know how to cope or express how I was feeling in certain situations. I saved up for my first camera and started constructing little sets and backdrops for self-portraiture in my room, where I quickly fell in love with the medium. In high school, I was the photo editor for my school’s yearbook and newspaper, and just kept pursuing art in college until I finally made the decision to switch my major from a BA to a BFA. I worked in art galleries on campus, was involved in student-run exhibitions, and jumped right out of my undergraduate program to pursue my MFA in Photography at Columbia College Chicago, where I had been wanting to attend for a very long time. Now I’ve graduated with my masters and am working full-time in my field.

JTD: When you and I met, we spoke about your experiences living in the South as a gay man and struggling to feel like you could be fully open about your identity. How did this experience affect both your life and your work? How has this changed now that you’ve spent several years in Chicago (or has it)?

KG: I carry a lot of conditioned shame that I try to resolve through my photographic projects and artwork. For the longest time, I’ve always felt the need to make work that deals with personal identity because I feel I have so much more to learn about myself. I struggled for a while when I first started making the work because I had no idea what to say, I didn’t know about my community’s history and language, and I had to really dig deep and educate myself. Growing up in the South, I didn’t feel there were a lot of people like me, because you feel that the world tries to hide you most of the time. Moving to Chicago, I was able to grow personally and as an artist in an environment that is more accepting and diverse. I’m learning to be kinder to myself through my photographic processes and am eager to turn the camera away from me and onto to others and make new connections.

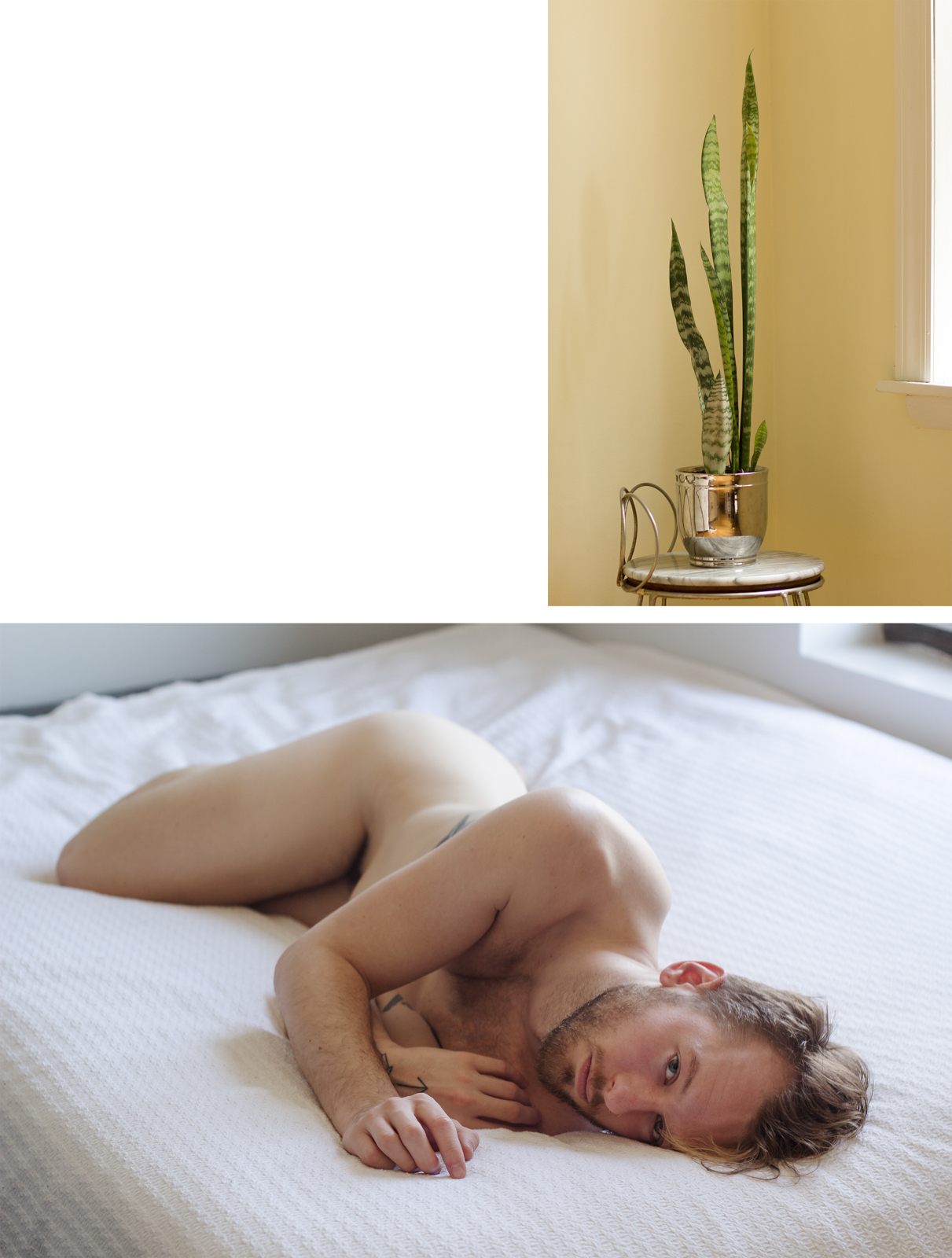

JTD: Tell me about your project The Way You Look at Me, which, you write, “reflects upon expectations of gender expression and performativity through the lens of a queer code.” How did it come to be? Is it ongoing or completed?

KG: My project The Way You Look at Me initially began with a Polaroid camera being passed back-and-forth between myself and Rich. We would make nude snapshots of each other and direct each other’s gazes, poses, and the overall scene. During this time, I was thinking a lot about that shame mentioned earlier, mostly sexual shame. As the project developed, I began to think more about queer signifiers through clothing and symbolism, as well as gestures. For me, I always felt insecure being labeled feminine or “too gay,” especially by other gay men. By performing different spectrums of gender expression, I am able to question the role of representation and true identity within photography and how this influences the act of looking at others. This project is complete.

JTD: What was your process for making work with someone so close to you? Were there moments when one of you wanted to make a photograph but the other did not? How did you navigate the inherent issues surrounding photographing such an intimate personal relationship?

KG: All of the images, which are based on my personal experiences, are created in my head and then sketched if needed. Before I made an image that included Rich, I would discuss my vision with him, set limits, and then schedule the shoots. When Rich is in that scene I usually give him the remote to release the shutter when he feels comfortable. This allows him to feel in control of his body, the experience, and that’s what I think creates that highly intimate mood in my image while still being constructed or staged. There were definitely moments of the photos feeling like work or not really connecting, and I think the most important thing about navigating the issues that come with making intimate projects like this is communication and distance. I think that trying to be objective as much as possible is important, although hard. Keeping clear communication about intent as well really helps make everyone feel comfortable about what’s going on.

JTD: Tell me about your video Slim Non-Masc Faggot Bundles Faggots. You exhibited this alongside The Way You Look at Me in your recent MFA thesis exhibition. How do the two projects overlap or inform one another? Do you see them as one larger project, or as separate entities?

KG: Slim Non-Masc Faggot Bundles Faggots is a performance video where I repeatedly select and bundle sticks to form faggots. The title of the scene references language used within gay culture mostly by white cis-gay men when navigating sex. In the 19th century, women made insufficient livings off gathering sticks to make fires at home, gaining the title “faggot-gatherer.” In the past, many household acts such as doing the dishes, folding the laundry, or repetitive household chores have been considered more feminine tasks. I use repetition as a traditionally femme act to reclaim the activity of bundling and challenge traditional gender roles within society. I believe that this video project definitely informs The Way You Look at Me by discussing expectations within the gay community, how individuals look at others, and the weight of external factors that create negative biases. I met Rich on Tinder, an app where you repetitively swipe left or right (Left for no, Right for yes) until you match people. The swipes usually are based off of the one second opinion of whether or not that person is attractive or “masculine presenting.” I feel that juxtaposing the two pieces in an exhibition creates tension around my questions of representation and authenticity.

JTD: Can you speak about the importance of visibility and representation, both in your work specifically, and also more broadly?

KG: I think visibility and representation is important in my work, however I believe I can push myself further when dealing with those topics and am super excited to do so in my next project. I use Slim Non-Masc Faggot Bundles Faggots to really criticize and reclaim language used by cis-white gay men in the community. I believe that, as a white queer cis-male, I have a responsibility to talk about and create conversations around the prejudices and sexual discrimination projected by those within the community. I think that in a bigger context, representation is extremely important. I think a lot about museum access and representation, and who is able to go to certain institutions and see themselves represented in some form or another.

JTD: What are some key influences for you, and/or what are you inspired by right now?

KG: I was really inspired by Rana Young’s The Rug’s Topography and D’Angelo Lovell Williams’ work when making The Way You Look at Me. I think creating and maintaining a creative community that I can share and process work with and talk about projects is something I’m looking to be influenced by now that I’m out of school. I’m feeling drawn to meeting new people and creating connections through making portraits.

JTD: What are you currently working on? What’s on the horizon for you as an artist?

KG: I’m currently working on the beginning stages of finding a new project. I’m beginning mind mapping exercises, making lists, and trying to find something that’s important to me to talk about through my photographs. I’m working full-time, however, I would love to get into museum volunteering or teaching classes on the weekend. I’ve taken a break since getting out of grad school; I’m feeling ready to get back into my studio practices.

All images © Kenneth Guthrie