Q&A: Kelvin Burzon

By Rafael Soldi | May 8, 2018

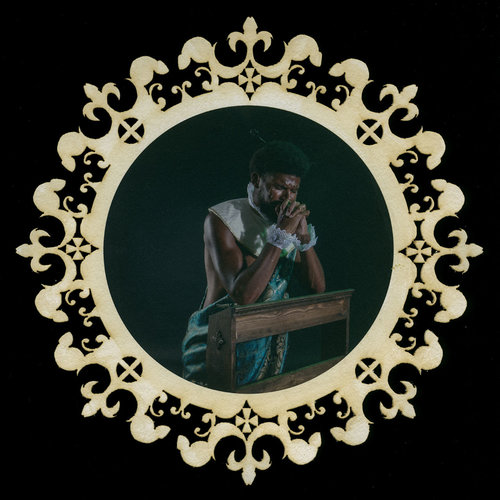

Kelvin Burzon is a Filipino-American artist whose work explores intersections of sexuality, race, gender and religion. He was born on March 26, 1989, in Bataan, Philippines. As a child growing up in a Filipino culture, Burzon’s initial ambition was to become a Catholic Priest. His work is inspired by cerebral influences growing up in and around the church.

Burzon recently received MFA degree from Indiana University's School of Art + Design where he developed his most recent bodies of work. There, he is a performing member of the African American Dance Company where he flourishes in a collaborative performance outlet. This outlet blossomed interests in critical race theory, photography’s role in people’s social identities, story telling, archival gaps and performance. He received his Bachelor's from Wabash College where he studied studio art and music. There, he became versed in painting, sculpture, ceramics and photography. He studied music history, violin and piano performance, vocal performance, as well as years of ethnomusicology. He was a musician and dancer in Wamidan World Music Ensemble in Crawfordsville, IN. He studied abroad in Florence Italy where he was exposed to a variety of religious works by Renaissance masters as well as studying oil painting techniques. Kelvin Burzon continues to push his work with inspirations from the past, recontextualized narratives and imagery of religion, paired with the never-ending stimulation and inspiration from the LGBTQ+ community. Burzon seeks to push the limits of his work by visually redefining and creating a new narrative for himself and those like him.

© Kelvin Burzon, The Living Bible

Rafael Soldi: You never planned to become a photographer. How did you end up pursuing an art career?

Kelvin Burzon: Actually, I was very hesitant to take my first photography course in college. As stereotypical as it may sound, felt the familial pressure to pursue medicine. Asian doctor I was to become. But, I was always good at art and wanted to take a course for means of stress relief. The only class left open was a black and white photography course taught by Kristen Wilkins. It was a three-hour course at eight o’clock AM; hence, I was always late and cranky. I never thought of photography as a valid art form. I’ve always fancied painting, drawing, and sculpture. So, I came into the course apprehensive. Long story short, I ended up throwing in the towel on my family’s dream of my future as a doctor and I chose art and music instead. I realized medicine was for serious people, and I was hardly serious. Except for when it came to photography. It had a way of demanding me to be serious. It forced me to face sincere and contemplative aspects of myself and life around me. It adhered itself into the way I saw everything and there was no way to shake it off.

© Kelvin Burzon

RS: How do the multiple dimensions of your identity—Filipino, American, queer, etc—show up in your work?

KB: Well, The work is prompted by American politics and social climate. Specifically, the inevitable collision of race, gender, sexuality and religion into politics. Filipino culture appears as a representation of the Catholic religion. I grew up in a culture inseparable from the church. And, I obsess about the customs, rituals and its visual language. I was most fond of Catholicism as the glue that perpetuated memories of my childhood in the Philippines. Lastly, queerness makes the final layer. My sitters all associate themselves as members of the LGBTQ+ community.

© Kelvin Burzon, from Noli Me Tengere

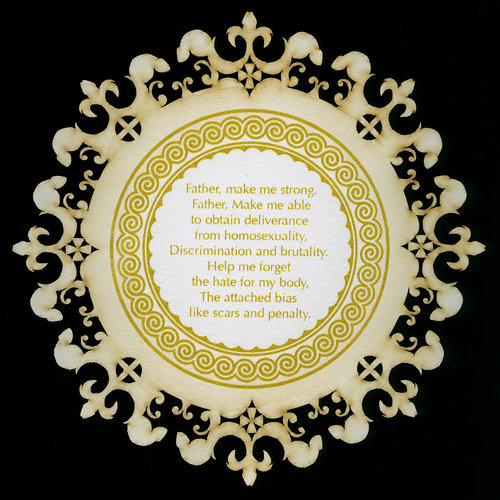

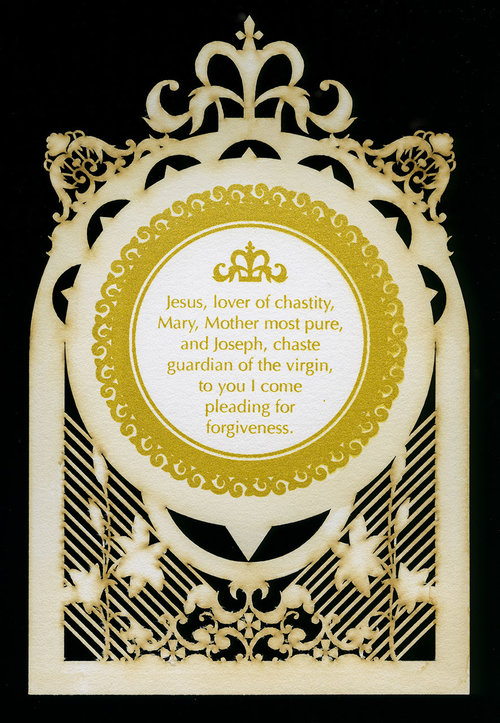

RS: Religion is a resounding thread running through your most recent bodies of work: Noli Me Tangere, Mea Culpa, Living Bible. Not only do you stem from a deeply religious background, but you also reside in Indiana, where Mike Pence signed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. In which ways are you borrowing from religious iconography and narrative to talk about sexuality, race, and gender?

KB: Religion acts as the base of the narrative and imagery. It is the visual foundation that I employ as a commonly understood language. I begin with the iconography, the narrative, and its deeply rooted significance in American and Filipino culture. I then pair that language with queer culture, sexuality and gender. I listen to my sitter’s stories, their life, and their identity and find a fitting depiction. By recontextualizing familiar religious narratives and imagery I point out discord, gaps in representation and disregarded issues all wrapped up in beauty and harmony that viewers intrinsically understand.

© Kelvin Burzon, from Noli Me Tengere

RS: I can tell just by looking at your work that you’re a perfectionist! Your lighting is dialed in, and your presentation is very deliberate. Can you tell me more about the part of your process that comes after taking the pictures? How important is presentation to you?

KB: As a performer and self-proclaimed control-freak, presentation might be the most important part of what I make. I’ve always argued that taking the image alone is only a small percentage of my process. The artwork is never done until an audience member consumes it. All images I make belong to a predetermined presentation, whether it’s meant to be in a diptych, a book, or the central image of an altarpiece. Presentation is never second thought, at most, it is first thought. I strongly believe in experience and performance, and that translates to my final products.

© Kelvin Burzon, Mea Culpa

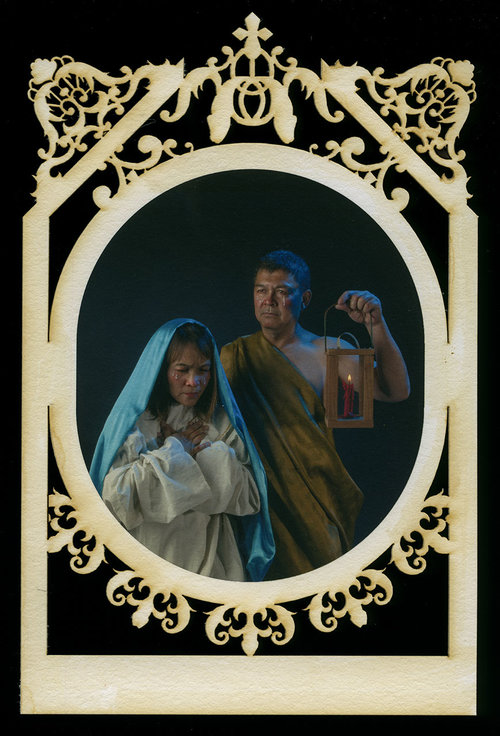

RS: Tell me about bringing your parents in to work with you in the studio. How was the experience of collaborating with them?

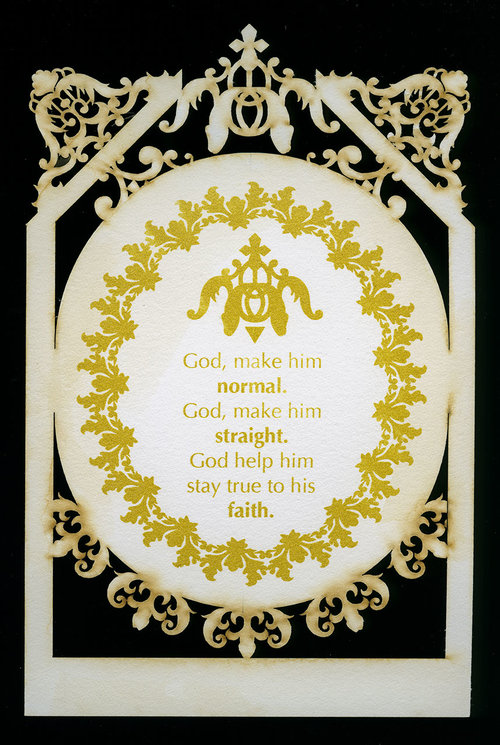

KB: My parents image, Mea Culpa: Maryosep, might be the most rewarding photograph I’ve ever taken. Yet, it still feels the most incomplete. (Maryosep is a Filipino compound word. It is the combination of Mary and Joseph and is often used as an expression of disbelief, surprise and amazement.) The Mea Culpa series stems from religious guilt and the appearance of religion by feelings of shame and remorse. The series is represented as prayer cards, laser-cut inkjet prints with screen-printed text on back. My parent’s image is paired with a prayer that reads, “God, make him normal. God, make him straight. God, help him stay true to his faith.”

The imagery felt the most incomplete for there is still so much to be said. I feel as if I’ve barely graced the surface on the amount of things my parents and I need to talk about. But, Maryosep was the most rewarding to make because it was my way of coming out to my family and revealing to them the work that I was creating. Never before that have I blatantly told them about my sexuality and lifestyle. It truly meant everything to me. I feel an incomprehensible amount of gratitude for them to lend me their image and help relate to the world the issues and struggles that I face with my work.

RS: You dabble in so many things—you’re even in a dance troupe! Outside of making photographs, what other interests do you have and how do they inform your practice?

KB: I’m interested in craft. I spend hours researching and watching instructional videos on wood working, sculpture and sewing. This appears in the handmade frames, set pieces, clothing, and props that I create for my studio work.

I’ve always considered myself a performer. I’m a violinist and pianist and have studied ethnomusicology and dance. I use this mostly in the studio. When interacting with a model, I use music to set the mood and to set a tempo, as if we’re about to dance. It informs our conversation and creates a cadence for both of us to exist in. My dance practice and movement vocabulary then takes the lead as I pose and instruct my models. I strongly believe that all portraiture image-makers should take at least one dance class in their career. Proprioception, or awareness of one’s body position and movement, is an important aspect of my studio practice. I have a flow of warming up the body, creating comfort, and movement exercises to achieve the body language and expression I am after.

RS: What's next for you?

KB: In about a week I will be leaving for the Philippines. I haven’t returned in eleven years and I intend to use the three weeks I am there to reconnect with family and the culture that I am using so predominantly in my imagery. I hope to reevaluate what it means to be Filipino in the perspective of a recently naturalized citizen of the United States. This trip will be a precursor to a new photographic series that will be responding to the surge of extra judicial killings in the Philippines.

RS: What are you obsessed with right now? (anything: a color, a song, an artist, food, a sport, a fad diet, your hair, whatever…

KB: Currently, I am obsessed with going to the movies alone. It sounds silly, but it’s something that I’ve always been afraid of doing. But, somehow being alone in a room full of pairs forces you to face a weird loneliness that by some means result in a feeling of accomplishment.

All images © Kelvin Burzon

Above: © Kelvin Burzon, from Noli Me Tengere

© Kelvin Burzon, Mea Culpa

© Kelvin Burzon, Mea Culpa: Maryosep

© Kelvin Burzon, Ectasy