Q&A: Kathleen Y. Clark

By Hamidah Glasgow | May 28, 2020

A Washington State native, Kathleen Clark lives and works in Southern California. She received an MFA from the University of California, Irvine, and a Bachelor of Arts degree from The Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington. Her work explores themes of history, social justice, language, and home. As a member of The Girl Artists of Portland, Oregon (1980-87), she received commissions and grants for collaborative performance and installation work from The National Endowment for the Arts, the Oregon Arts Commission, and Seattle Arts Commission and Portland’s Metropolitan Arts Commission. The group exhibited at COCA, Seattle, the Portland Art Museum, Southern Exposure, San Francisco, LACE, Los Angeles, and PCVA, Portland. Over the years, she founded and directed several Los Angeles art and photography galleries; served as editorial photo editor at Los Angeles magazine, LA Weekly and Sunset magazine, and directed publicity at the NW Film Center in Portland, Oregon. She also served as photography faculty at USC and Art Center College of Design, where she continues to consult.

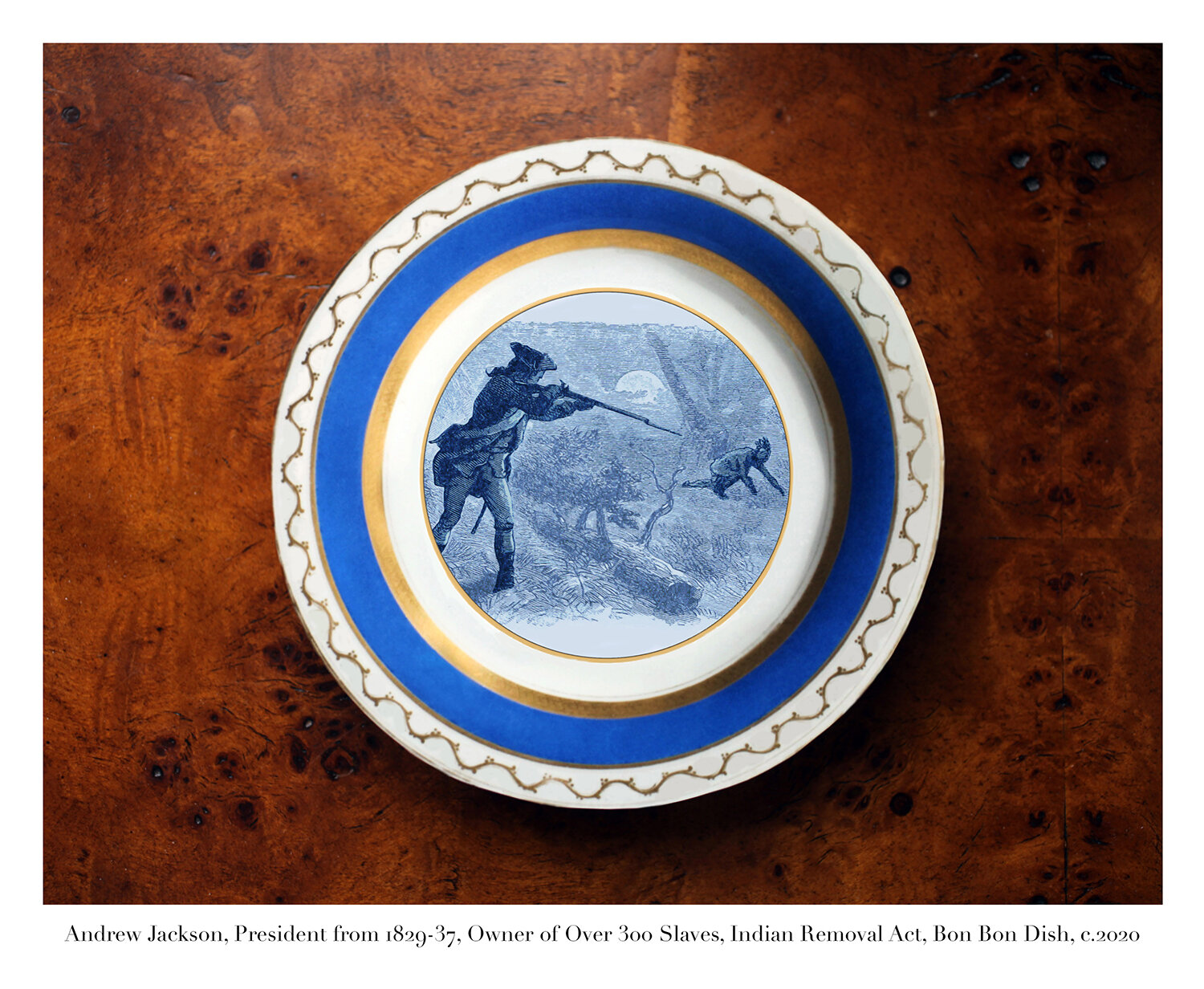

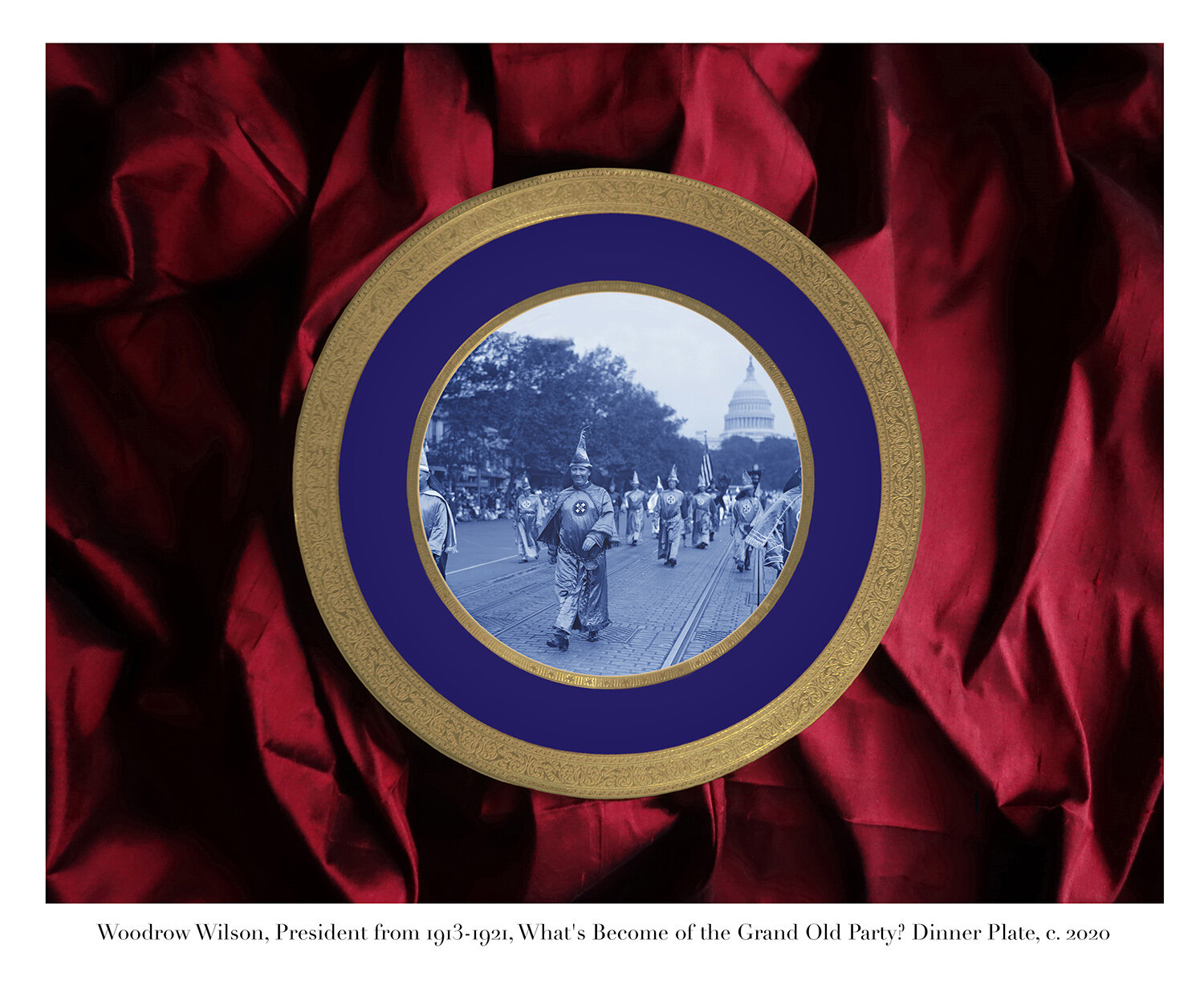

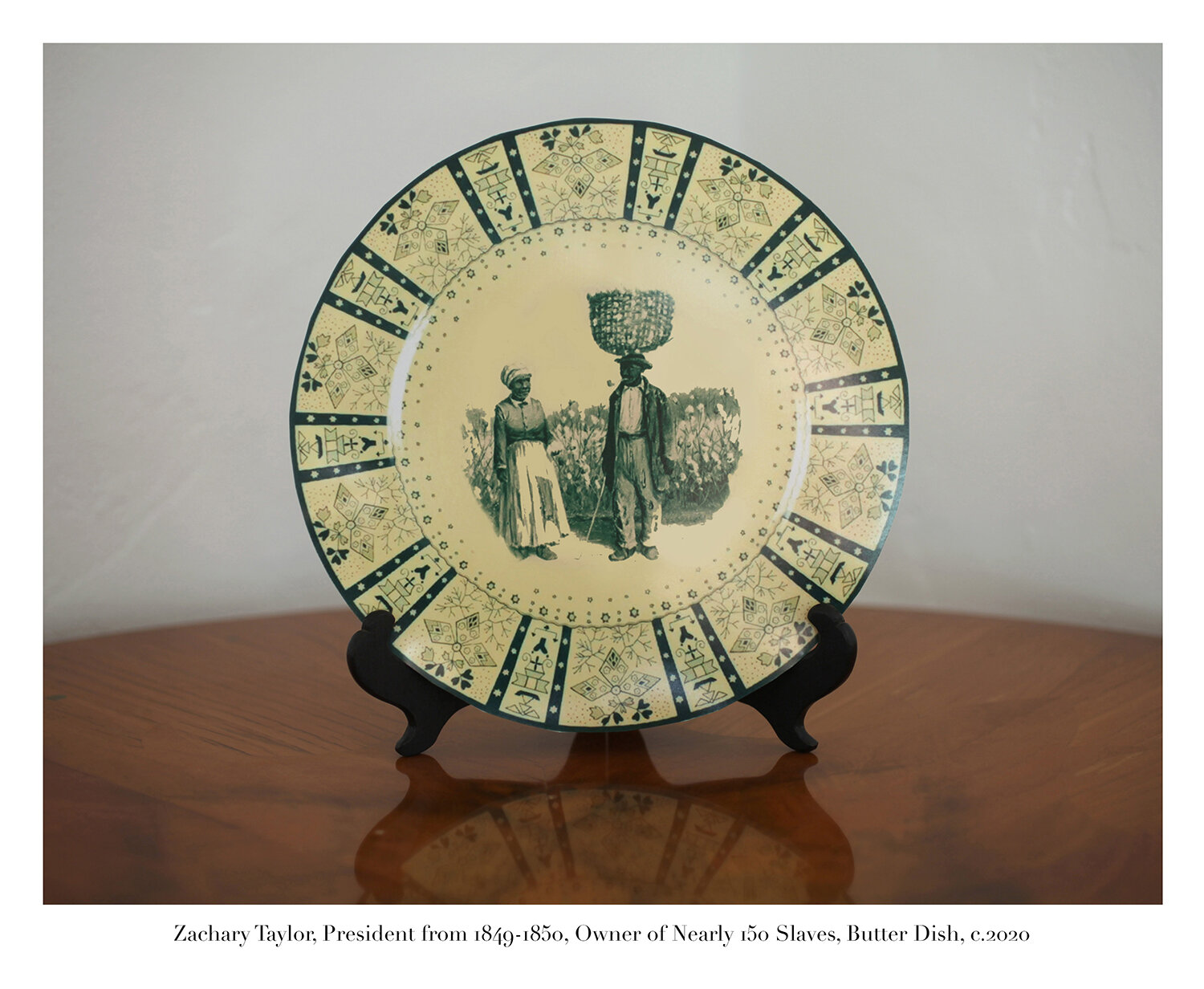

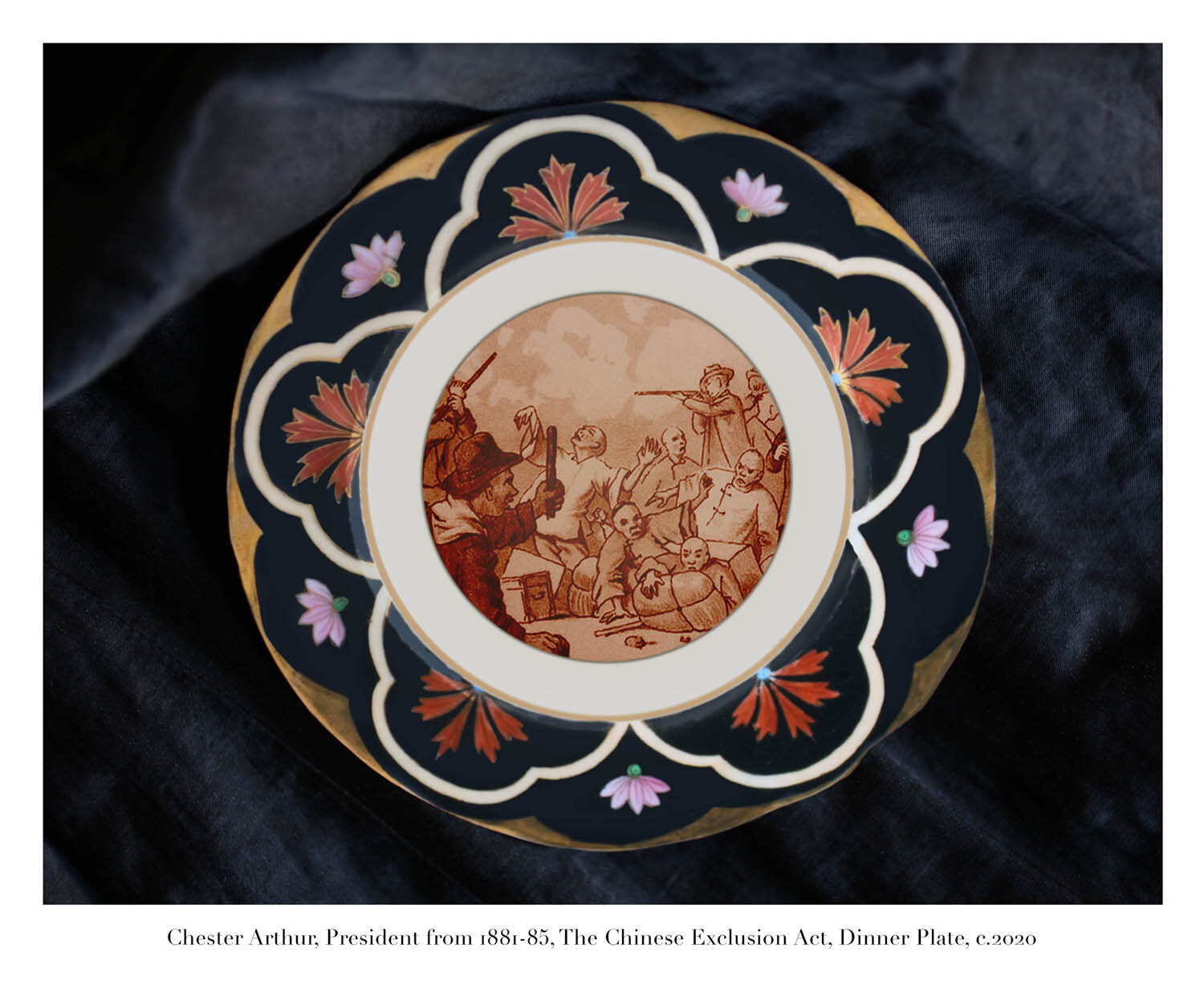

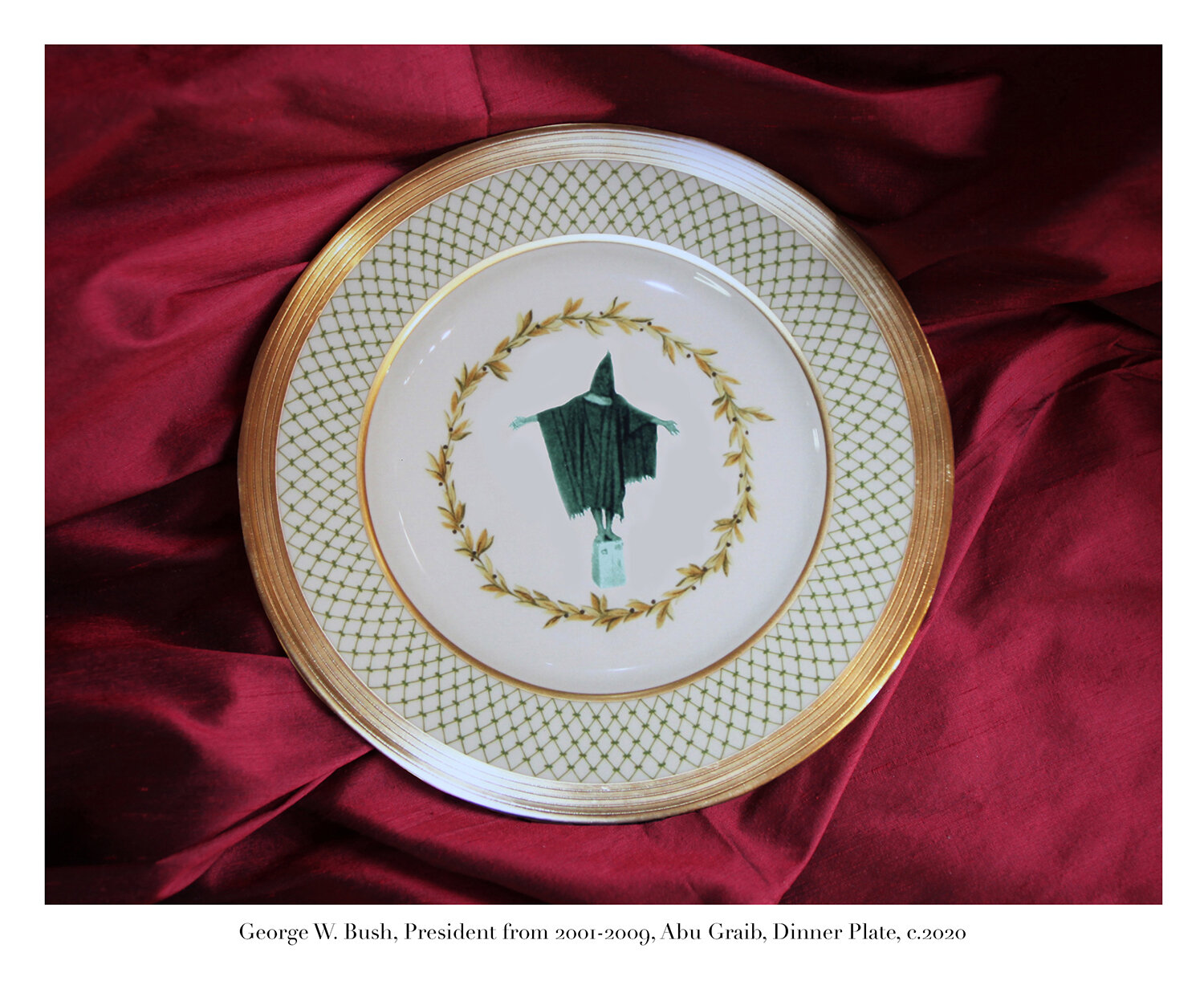

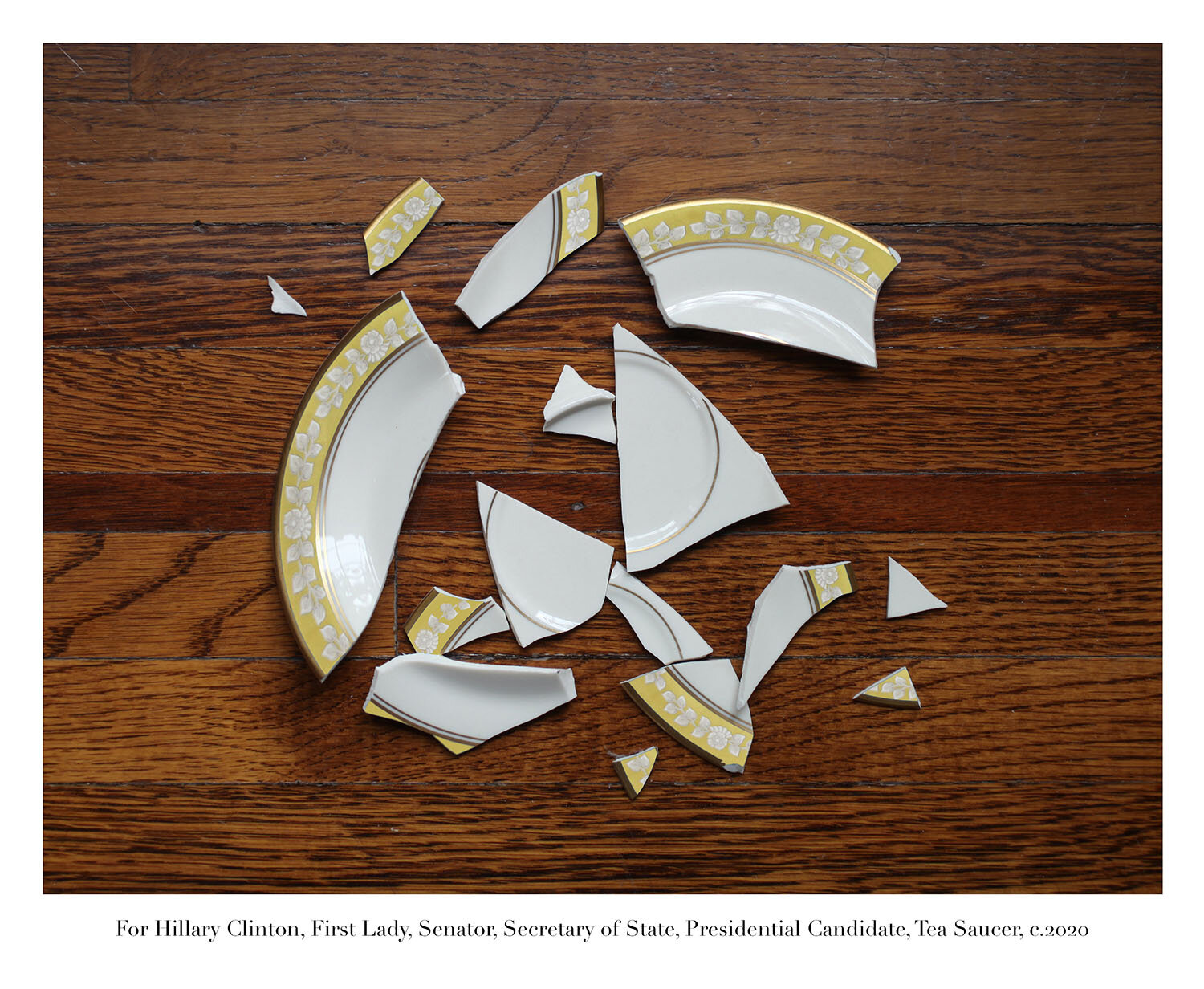

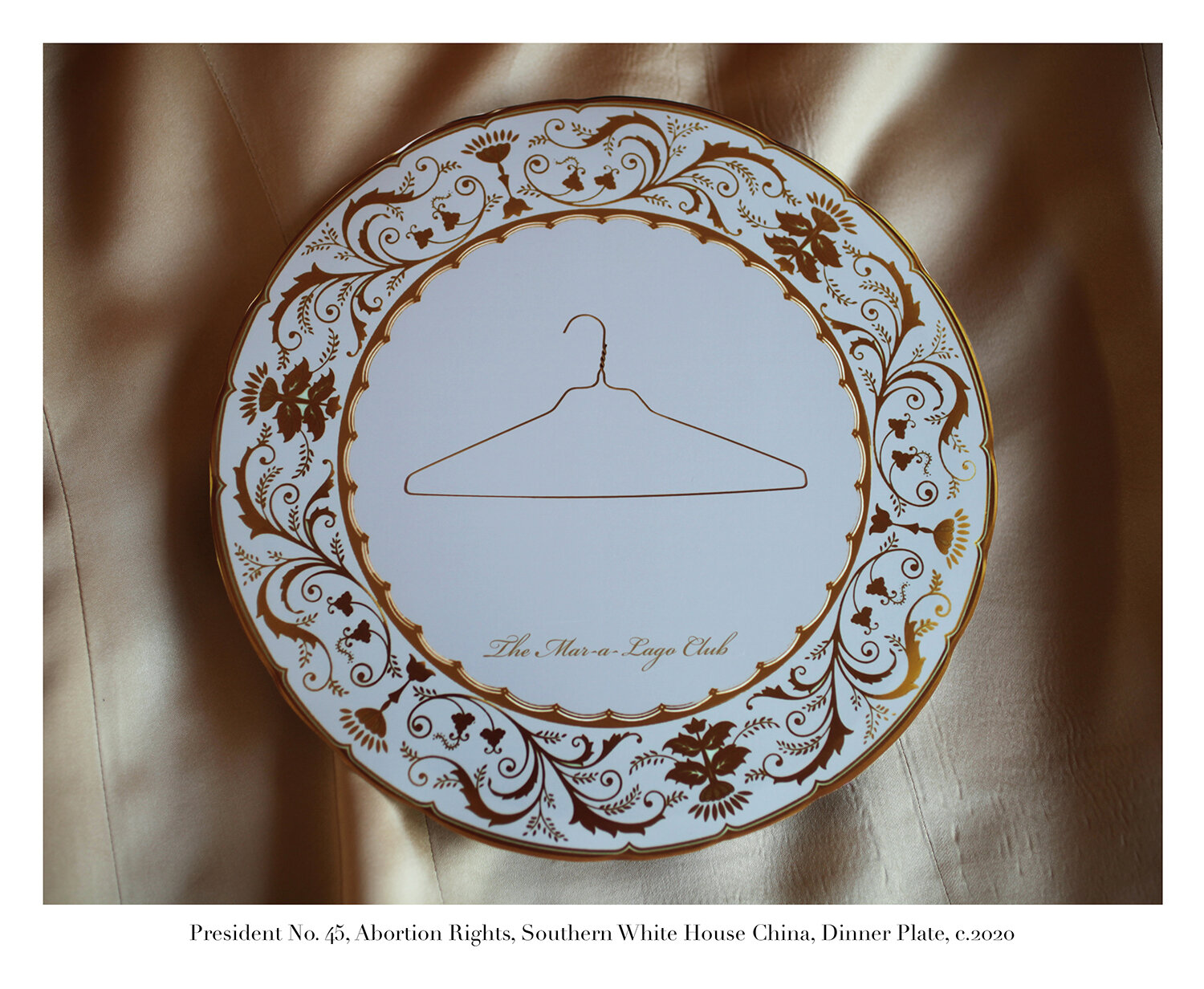

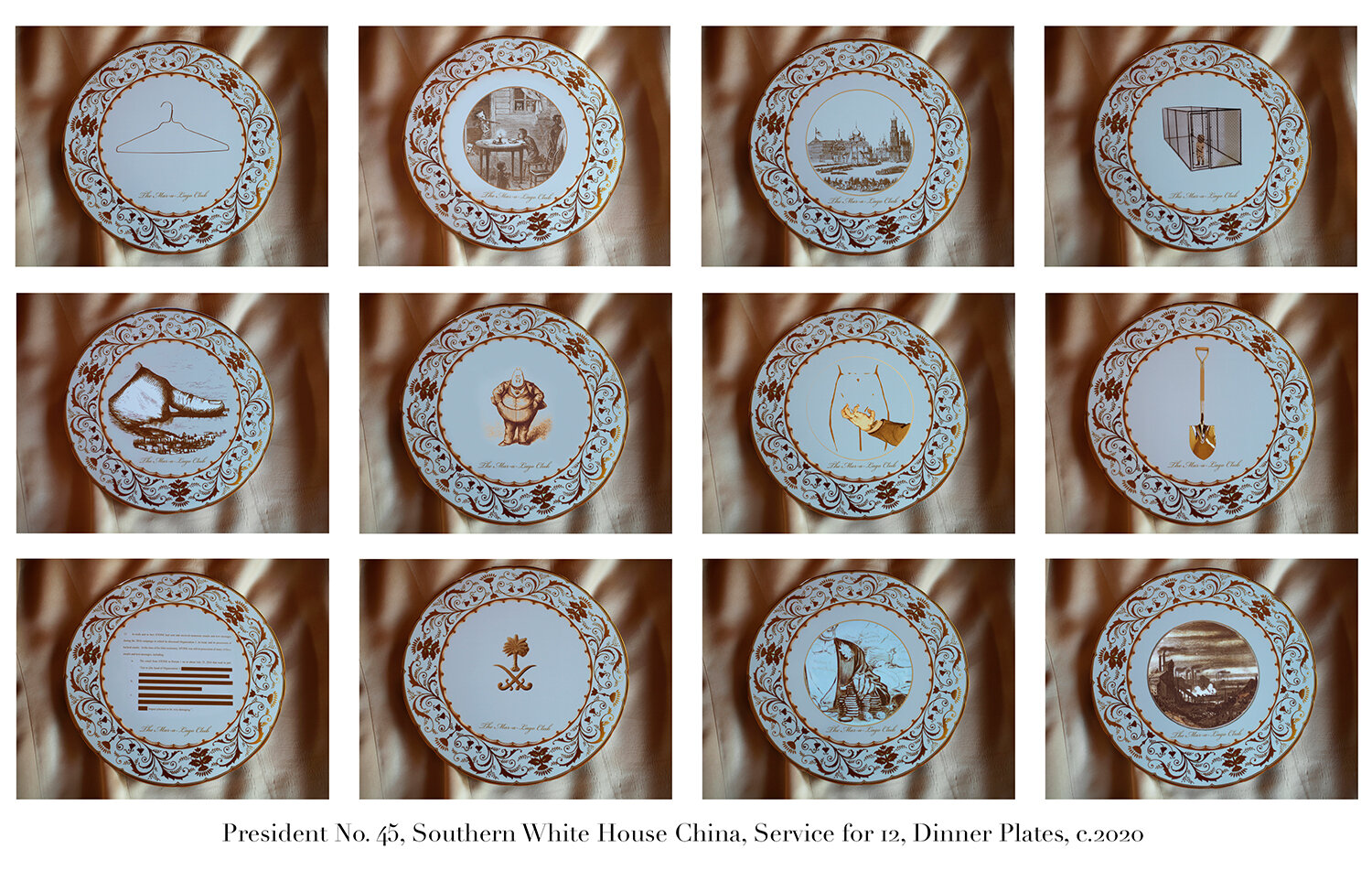

Inspired by early political illustrators who used their explosive imagery to reveal the injustice behind the country’s facade of equality, these re-creations look at presidential contradictions and pivotal judgements made throughout the nation’s history. My intent is to shine a light on often-destructive events which happened by decision or neglect within each administration, providing a stark contrast to the assumption of civilization and culture set around historic dining tables. – Kathleen Y. Clark

HG: What got you started on the creation of the series, The White House China?

KC: I closed down my gallery, Spot Photo Works, in February of 2016. It was the height of the campaign for the presidency and Trump was taking the political discourse into hideous and divisive depths. I was looking for a new project when my wife asked if I’d want to tag along on a trip to Washington, D.C. I jumped at the chance. I’d never been there, and really wanted to see it while Obama was still in office. I went looking for the iconography of America in architecture, sculpture, and public works. With her connection to U.S. Representative Adam Schiff, we secured tickets to the White House as well as a private tour of the Capitol and some insider events at the House and Senate office buildings-things I could never attend as a regular traveler. It’s funny to think now of us stowing our bags in Adam Schiff’s office. One of his interns was the son of a news editor, an old colleague. He was a local hero in LA, but nothing like the star he would become with 45’s Impeachment. I remember glancing around at paper weights and family photos (he was out at the time) and thinking how mundane and low key it looked -no pomp - nothing fancy.

At the White House, I took some photos, but it was more like visual note taking that I would translate later. I looked as closely as I could at the china collection across a velvet rope. When I was young, there was a big scandal about the huge sums Nancy Reagan spent on new china, it was familiar and intriguing. The Smithsonian Museum of National History has an amazing display of gowns of the First Ladies in all shapes and sizes and there were also samples of actual White House State china from a range of administrations that I could see close up, but I had no intention of working with the china imagery at that point. I just took more notes.

I also spent some time in the collections of the Daughters of the American Revolution. They have a beautiful genealogical library and I dug in there a few afternoons looking for ways my ancestors may have intersected with historical events in the American historical timeline.

The first drafts of The White House China plates came about the following July. I was looking through an old case of transparencies I have of antique engravings on the history of slavery. The images struck me as looking like toile patterns and I realized slavery illustrations could combine with china patterns and they would look as though they belonged together. That’s when I recalled the presidential china. My first versions were funky, but I heard myself laugh out loud. There was nothing funny about the images, if fact they were bleak and frightening. When I realized how the sinister slavery images mixed so easily with the sweetness of the flouncy floral and garland borders of the presidential porcelain, I just thought “whoa, this works – message delivered.” I recall while making the first plate I kept thinking “the contradictions of Thomas Jefferson.” It included Jefferson’s plate rim patterns along with engraved shackle images, which I later found again in the collection at the Library of Congress.

At first, I thought I could create a series from the Founding through the Civil War, to deal with slavery and the massacres of Native Peoples. That alone, seemed a huge project. Immediately, though, the second image that came to me was the Abu Graib photograph for George W. Bush. Then I knew I had to make an entire set – one for each president.

The concept behind all The White House China photographs, even the images that aren’t about race, includes the contradictions within each presidency. Each image has a certain elegance at odds with greed, avarice, violence or failure of some type. The use of decor and public displays of grandeur masks menacing subtexts.

HG: What was your approach to the research behind the project?

KC: I looked at everything I could find from personal collections, the Library of Congress, the National Archives, various museum, state and library archives. I collected, read, and stumbled onto related topics, constantly discovering a million things I didn’t learn in school. I started looking at auction houses and political paraphernalia. There were two distinctly different research tracks: one was the political narrative of what happened historically that became the central image of each piece and the other track was researching the actual china patterns.

Halfway through the project, I found an old book on political ceramics and discovered a porcelain Jasperware medallion that showed an image similar to one I was using of a black woman in shackles called Am I Not a Woman and A Sister? It was made by the Wedgwood ceramics company to promote the cause of the abolition of slavery in the late 1700s. I had no idea that ceramics had been used in this way in the distant past, but it felt right to follow in its footsteps.

Later, on a roots and photo road trip with my younger brother to Virginia and West Virginia, we found more abolitionist china at the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University. They were dishes and teacups for children to teach them of the horrors of slavery.

HG: I’m imagining that there was a lot of information to sort through between the political slant given by the authorities at the time and the truth as you unearthed the details, is that correct?

KC: I’m interested in history, but I’m not a historian so my research in some places was rigorous and other places it was pretty superficial. I read some early correspondence and spent more time looking at historical imagery and ephemera than reading old texts. I did read newer texts about various administrations and acts and laws, trying to understand more of what the presidents did or didn’t do and what they stood for.

I also used genealogical research applications, because I’d been trying to string together an understanding of my paternal family line that went through tobacco country in colonial Virginia. That research led to discovering a particularly heinous 7x Great Grandfather, who placed an ad for his runaway slave in 1770 Chesterfield, and his family’s slave cemetery where the remains of 81 human beings had been found. Without knowing it, I shared a complicit heritage and that really got to me. It really spoke to the tragic flaws of foundational America and in my own lineage.

Meanwhile my son, who is adopted, discovered that he’s 16% African American and along with gaining a wonderful new branch of family stemming partly from early Creole New Orleans, I began to see how our own existence paralleled with the life of the country.

All roads were merging.

HG: That is a deep revelation of your family. How do you move forward with that knowledge?

KC: I put it into the work. I was interested in knowing my own history so I might infuse the historical work with the personal. More contemporary iterations of my family tree moved westward and thankfully evolved with more humanitarian ideas. Still, it came as a shock. Somehow the old quote comes to mind: “We can’t know where we’re going if we don’t know where we’ve been.”

HG: There is much revelation about previously enslaved families yet not much about the families that held enslaved Africans. Is that something you intend to follow-up on?

KC: I’ll keep digging into the historical as it fascinates me on a personal level. I don’t know where that will take me. I don’t plan on further work on enslavement, but I can’t say that it won’t come up again. There’s certainly an abundance of reasons in contemporary society to keep at it. Still, empowerment is sounding awfully good to me right about now.

HG: What was the biggest surprise you found in your research?

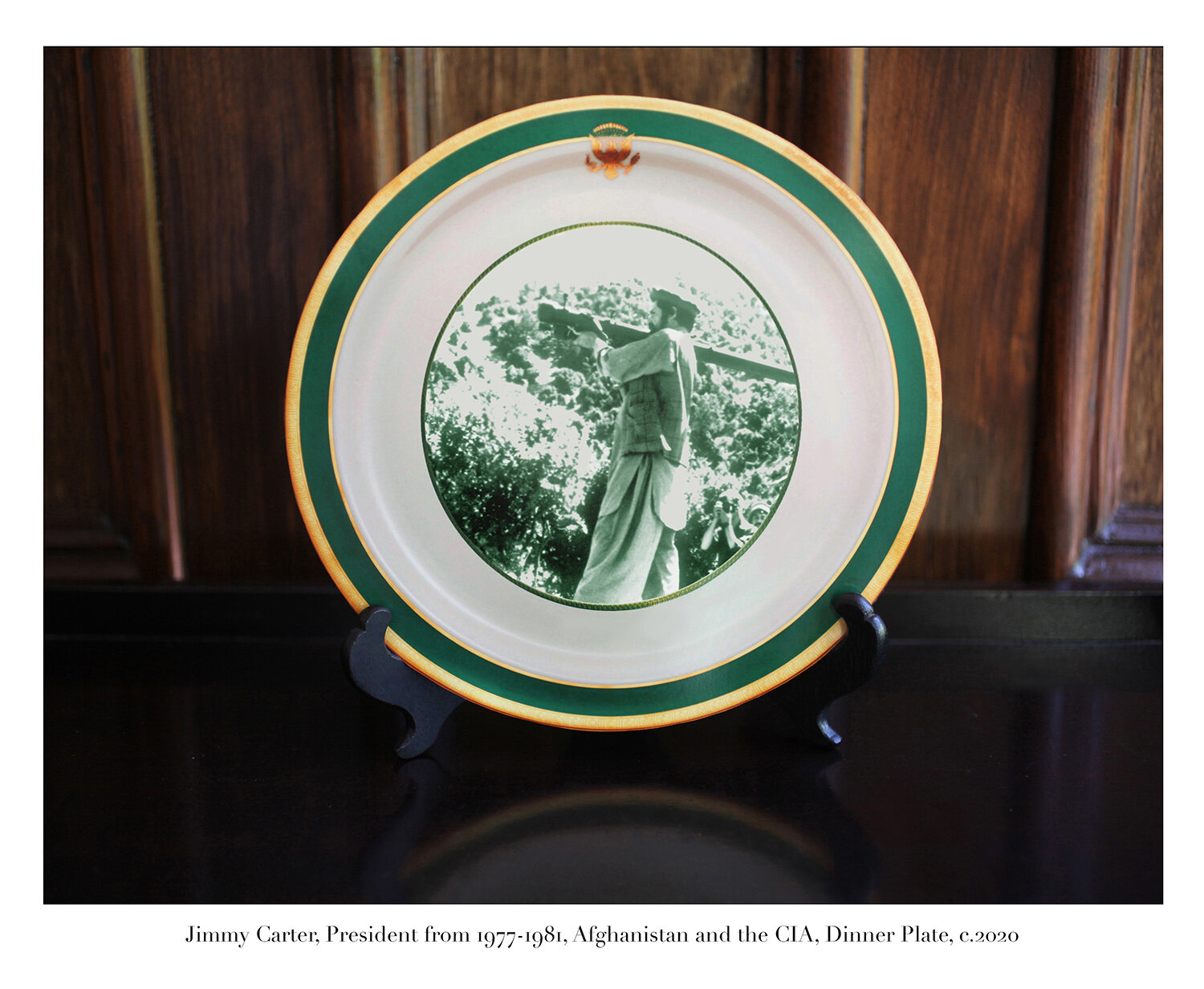

KC: Jimmy Carter. He’s the first president I ever voted for and I got him wrong for the longest time. I think I put blinders on because we see him now as such a generous human being. I mistakenly didn’t dig deep enough when researching him and my first images for him were nothing but positive. This winter I sat down with my long-time friend, the New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis. We poured over all the pages in my book dummy and she gave me the best, most rigorous and useful critique. Carter was a sticking point. She was sure there was something darker that he was responsible for and just couldn’t put a finger on it. The next day she sent a link to an article in The Nation which brought back Carter’s involvement in what became America’s deepening mire of Afghanistan. Carter pretty much did the wrong thing by trying to do the right thing.

Actually, there was another really great surprise. I knew that John, Abigail and John Quincy Adams were opponents of slavery, but in reading about JQ, I found that following his presidency he served as attorney on behalf of the escaped slaves of the Amistad ship. He presented their case before the Supreme Court and won. In 1841, the Mende tribesman were returned to Sierra Leone. The concepts behind the majority of the photographs in the series deal with the time period each president served, but I broke form with JQ Adams by memorializing an historic contribution that fell outside of his presidential term. I think I just needed something to be positive.

HG: Is there one plate that hits you the hardest? That has the most emotional impact for you personally?

KC: As tragic as many of the images are, I feel the most moved by the plate for Barack Obama. It was one of my earliest, and I can still feel the plate in my hand while imagining what might happen. It was November of 2016, just after the grim election. It was the diametric opposite of how we all felt when candidate Obama spoke at the Democratic Convention that summer. It was the opposite of every time he ever spoke with compassion and elegance and intellect during his 8 years in office. He made us proud every time. The great wound was discovering just how many people felt the opposite and that was terrifying. I was utterly repulsed by Trump. I was sure he would do everything he could to rip apart anything Obama ever touched.

The subtext was that my parents and a brother became antique dealers in the 1970s, and I dabbled. That personal connection to objects colors the entirety of The White House China series. Deciding to make Obama’s plate turned backward related to the common practice in our house to flip an object upside down to read its maker’s mark. I was reckoning with what I felt certain would be an effort to erase all of Obama’s accomplishments. The fact that the label says The President’s House, Washington, Obama, along with an image of the Great Seal, is an act of defiance and ownership. He may be shoved aside, but we will remember.

HG: One question, I don't know how you identify. Do you identify as white? If so, how do you manage to make this work that is largely informed by white history? As you mentioned, there is so much that we don't learn in school. Did you fine yourself questioning all the sources and their white bias?

KC: I grew up in suburban largely white schools with a few Asian kids, a few African Americans and a few Latinos. As a white kid with fairly dark skin, from a young age, I was often asked whether or not I was Native American, Polynesian or Mexican. I remember thinking at age 5, that people seemed to be asking something else, or there was something behind the question and I wondered what it was and why it mattered?

Until recently, history has been seen through the eyes and pens of ruling powers, who controlled the spin. In America, white historians monopolized information about the White House. I would suppose that the bulk of U.S. citizens didn’t realize that until Michelle Obama spoke of watching her children play on the lawn of a house built by slaves, that in fact it was true. I wasn’t aware of it myself until seeing John Adams, the TV series with Paul Giamatti. Probably most people don’t know that the Statue of Freedom on top of the Capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C., was in fact sculpted by Philip Reid, an African American slave.

Journalism too, which was a source for many images at the core of The White House China, was controlled and operated by Caucasian publishers. Illustrators stood on both sides of the racial debate and images in the national visual archives reflect both ideas of equality and white supremacy. It doesn’t hurt to have an African American woman, Carla Hayden, currently directing the Library of Congress. However, there’s a lot of untold history to make up for in the national record, and that was before 45 started his dismantling.

I did question whether the story of colonialization and racial prejudice was mine to tell. I can’t speak to Black trauma or Native American trauma or Asian American trauma. It’s not my place. I can, however, speak to the role that Whites have taken in perpetuating it. It was shocking to me to discover all the eras in history where fear of immigrants and rampant prejudicial violence permeated American history.

Bias is everywhere and ignoring it won’t make it go away, nor will it allow a more complex look at identity. I also think it’s just important to stand up for each other.

HG: Of course, as white women we have no place to speak to the trauma of other people, but we have the responsibility to own our part of that ongoing trauma. Historically, white woman have ignored the hardship of others and placed themselves above the fray. If our families have been here for a while, mine have, we are part of the problem. Our ancestors created/perpetuated the institutional systems that exist today. In my opinion, we have to speak about this and teach people the history that is not told in school.

KC: Years ago, I attended a talk by Bell Hooks, and she said something about how we all needed to "decolonize our minds." There's just so much hard-wiring that needs to be re-programmed.

I think fully balanced education is desperately needed, and all Americans need to be schooled on the role of institutional racism. When it seemed Hillary Clinton would be elected, I thought one of the first things needed was a great boost in K through 12 education - in civics, history, and general literacy. Sadly, no catching up was done, and the damage is deeper than ever. Yes, of course, I believe in personal responsibility and active educational anti-racism.

HG: Thank you for sharing your work!

KC: Thank you!

All images © 2020 Kathleen Y. Clark