Q&A: karen haas

By Jess T. Dugan | August 25, 2016

Karen Haas has been the Lane Curator of Photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston since 2001, where she is responsible for a large collection of photographs by American modernists, including Charles Sheeler, Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and Imogen Cunningham. The Lane Collection, which has recently been given to the Museum, numbers more than 6,000 prints and ranges across the entire history of western photography from William Henry Fox Talbot to the Starn twins. Before coming to the MFA, she received her MA from Boston University and held various curatorial positions in museums and private collections, including the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the BU Art Gallery, and the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover. Her recent activities include exhibitions, Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott; Edward Weston: Leaves of Grass; and Bruce Davidson: East 100thStreet; and publications, An Enduring Vision: Photographs from the Lane Collection; MFA Highlights: Photography; Ansel Adams; and The Photography of Charles Sheeler: American Modernist.

Jess T. Dugan: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. Let’s start at the beginning. How did you discover your passion for curating, and what led you to your current position at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston?

Karen Haas: I discovered my love of art history when I took my very first survey class in college having never really known that there was such a major until I got there! My parents had always taken us to museums as kids and as a result I felt very comfortable in all types of museums early on. To gain curatorial experience as an undergraduate art history major I did a series of internships that really set me on the path I still find myself following today. One was at the Yale University Art Gallery, which was the local museum nearest my home in Connecticut and gave me a basic grounding in what a curator does in a relatively small (but spectacular) collection. The other was at the wonderfully quirky (but also spectacular) Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum here in Boston, where I ended up working for the next thirteen years after I graduated from college. During that period at the Gardner I decided to go back to school part-time and as a grad student at Boston University I discovered the history of photography at the same time that I met and fell in love with a photographer and that really sealed the deal – there was no looking back and I’ve been focused on photography ever since. After that I worked at a number of different museums and private art collections, including the Boston University Art Gallery, the Addison Gallery of American Art, and since 2001, full-time at the MFA, Boston.

Karen Haas at the MFA Boston, 2015.

JTD: As with any occupation, there must be parts of your job that are tedious or difficult and other parts that are exhilarating and inspiring. What is your favorite part of being a curator?

KH: My favorite part of being a curator is interacting with the public. One of the major reasons I never finally completed my PhD was that I couldn’t handle what felt like the “ivory tower” aspect of academia. Having already worked in museums for years by then, I wasn’t happy holed up in the library just doing research and I wanted to work on projects that really spoke to people and write books that would get read.

JTD: Tell me about the Gordon Parks show you organized for the MFA. How did it come to be?

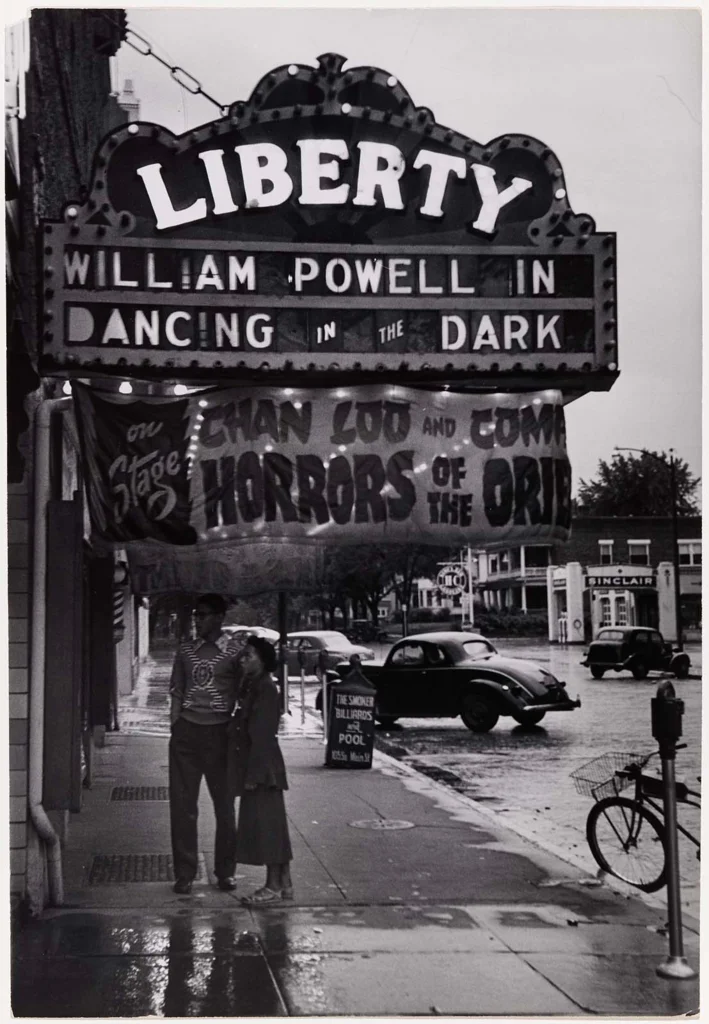

KH: The Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott exhibition (that opened at the MFA, Boston in January 2015 and has since traveled to the Wichita Art Museum and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) grew out of a completely serendipitous encounter. I was asked to write the photography entries for a recent catalogue, Common Wealth: Art by African Americans in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and was trying to learn more about a Gordon Parks photograph in our collection that was simply titled “Young African American couple in front of segregated movie theatre” and had never had a location or secure date attached to it. So I contacted the Gordon Parks Foundation where I discovered that our photograph was taken as part of a 1950 assignment for Life on segregated education that in the end never ran in the magazine. I was fascinated to delve into the riches of the picture files at the Foundation and subsequently read all of Parks’ Life notebooks and correspondence in the archives at Wichita State University to learn more about his plan to seek out his eleven classmates from the all-black elementary school they had attended in Fort Scott, Kansas and find out where their lives had taken them in the decades since he’d been back to his hometown. Luckily for me the Foundation invited me to write a fully illustrated book on the Back to Fort Scott story and they were willing to lend the virtually unknown prints for the exhibition, which was also incredibly exciting.

Gordon Parks, Outside the Liberty Theater, Fort Scott, Kansas, 1950, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Sophie M. Friedman Fund, © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

As my friends and colleagues will tell you I became obsessed with finding the now-lost layout of the summer of 1950 Life photo essay and, when that turned out to be impossible, trying to piece together the story myself from the photographer’s notebooks and my own research into the lives of Parks’ friends and families. When Parks arrived back in Fort Scott, a small agricultural/railroad town in the southeastern corner of Kansas, he was surprised to discover that only one of his classmates was still living there and that everyone else had embarked on the Great Migration to a variety of Midwestern cities in search of opportunity and freedom from segregation for themselves and their children. He made the decision to follow the steps of their northern exodus and managed to track down all but two of his friends in St. Louis, Kansas City, Detroit, Chicago, and Columbus, Ohio. Modeling his series of portraits of his classmates on Grant Wood’s famous painting, American Gothic (1931), Parks consciously posed his subjects and their spouses and children in front of each of their homes in the hope of countering widespread stereotypes of black families and presenting them as sharing the same aspirations and dreams as their white counterparts. Had the piece not been bounced in the end by the U.S. entry into the Korean War, Parks’ decision to try and tell the story of segregated education through the lens of his African American friends’ experiences would have been truly groundbreaking for a conservative weekly publication like Life which reached an audience of millions of mostly white middle-class readers in the years before the Civil Rights movement began in earnest.

Gordon Parks, Husband and Wife, Sunday Morning, Detroit, Michigan, 1950, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of The Gordon Parks Foundation, © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

JTD: You made several trips back to Kansas and surrounding locations to conduct research for the exhibition. What was your process of organizing, researching, and curating the show and corresponding publication, start to finish?

KH: Inspired as well by Isabel Wilkerson’s book, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (2010), my husband (who is a photographer and head of the MFA’s studio) and I decided to take some personal vacation time and try to retrace the routes that Parks’ friends took to all these different cities. Armed with their addresses copied down from the photographer’s notebooks, we searched in vain for any sign of the homes that the Fort Scott families had occupied in 1950 and were saddened to find empty lot after empty lot in the once-segregated neighborhoods now vacant and abandoned after all these decades. It was such an eye-opening experience for me, as a New Englander having grown up in the 1960s and 70s I realized how much I still had to learn about the beginnings of the Civil Rights era, Brown vs. Board of Education, and the painful history of segregation in education, employment, and housing, in the Midwest in particular, but in Boston as well. I’d visited Chicago many times, but never had any real sense of the city’s South Side, which was really the epicenter of African American life in this country during the postwar period and the place where Parks found three of his elementary school friends who had put down roots only a mile or so apart. One family was enjoying a very middle-class life, another was just barely scraping by in a cramped kitchenette apartment, and the last was mired in an abusive relationship and a seemingly hopeless existence. These three families represented the entire range of experience of Parks’ generation and the fact that they had all come from the same beginnings seems to have inspired them to share their very personal narratives with him in a way that they would not have had Life sent an anonymous white photojournalist out to report the same story.

Gordon Parks, Tenement Dwellers, Chicago, Illinois, 1950, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of the Gordon Parks Foundation, © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

JTD: What was the reaction to the exhibition? I assume there must be a ripple effect, inspiring new or renewed interest in Parks’ work and leading to conversations about identity and diversity. What has come from the exhibition thus far? What are your hopes for its lasting legacy?

KH: The reaction to the exhibition here in Boston went way beyond any of our expectations! NY Times reporter Randy Kennedy wrote a wonderfully thoughtful piece entitled “A Long Hungry Look” that greatly increased public interest even before the show opened in January of 2015 and I was thrilled that an exhibition of just over 40 photographs inspired so much positive press overall. Certainly most of the credit for that goes to the power of Gordon Parks’ black-and-white photography and his fame as Life magazine’s first African American staff photographer, but I think there was more to it as well. Now it seems a bit like ancient history (as sadly so much has happened since then), but our research trips throughout the Midwest took place soon after the public unrest following the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and we saw firsthand the boarded-up windows and other physical signs of its aftermath. So it came as no surprise that the topic of black lives resonated with our museum visitors, but what many people especially responded to was the way Gordon Parks managed to capture the strength and dignity of these small nuclear families who had posed for his camera some 65 years before, rather than simply presenting them as victims of an unjust system. It is easy to forget that this was a period in which it would have been dangerous for a black man to even look a white person in the eye when walking down a city sidewalk, so photographs like Parks’ would really have been rare to discover in the pages of the illustrated press of the day. But, as I mentioned to you, Jess, even seeing Parks’ images of the Detroit couple, Pauline and Bert Collins, featured on the massive banners on the façade of the Museum of Fine Arts during the run of our show was something that gave me a real sense of pride, even though we would all agree that such attention today is long, long overdue.

MFA Boston, 2015.

The ripple effect of the exhibition is somewhat difficult to measure, but I’m very pleased that it has now travelled to the art museum in Wichita, where the photographer’s archives are held in the Wichita State University library’s special collections. I felt a bit like I was taking the work of a local hero home, as Parks is such a beloved figure in Kansas and the public there is so familiar with his life story and extremely knowledgeable about his long and varied career. Wichita’s other two museums hosted Gordon Parks-related and Civil Rights photography exhibitions to coincide with WAM’s as well, which was an added bonus. Richmond, where the show is now on view, is another ideal venue because Virginia’s state capital has such a large African American community to begin with and its own well-known history of slavery, the Civil War, and hard-won segregation and Civil Rights battles. I was also pleased to realize that the Back to Fort Scott show at the VMFA would be on view opposite a large exhibition of Kehinde Wiley paintings, which I imagine will inspire many great conversations on the topic of black portraiture over time and across media.

My hope is that the Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott catalogue will help insure that there will be a lasting legacy for the exhibition. Books really have that power, as they live on even long after the show’s tour is complete and the objects are back in storage. And, in this case, the exhibition and publication are part of a larger series of projects that have been organized by the Gordon Parks Foundation and a number of museum curators across the country, with each project centered on a single Life magazine photo essay and each with its own beautifully printed book by Steidl. The cumulative effect of all these related projects has been a growing understanding of Parks the man and the pivotal importance of his career at Life, as well as a much more varied and nuanced look at a single photographer’s oeuvre than is usual. I’ve also learned that my book has brought far-flung Fort Scott families together and encouraged them to continue to share their stories with younger generations who might not have met Gordon Parks personally or necessarily known that their relatives were the subjects of a long-lost Life magazine story.

JTD: You and I have previously spoken about the lack of representation of people of color within major museum exhibitions and collections. Specifically in regard to the Gordon Parks show, you received feedback from visitors of color that they were moved to tears seeing his work featured on the banners that hung in front of the museum. I had a similar experience a few years ago seeing the banners for Catherine Opie’s retrospective at the Guggenheim along the streets of New York. There is incredible power in seeing oneself represented. Yet, for people in marginalized communities, this experience is unfortunately an exception rather than the norm. How do you view the role of both artists and curators to create, exhibit, collect, and publish representational media outside of the dominant realm?

KH: As a curator whose particular mandate it is to work on American modernist photographers, such as Edward Weston, Charles Sheeler, Ansel Adams, and Imogen Cunningham, in the MFA’s Lane Collection, I nevertheless try to make as many inroads as I can into righting the imbalance of representation of marginalized communities. The Gordon Parks project, as I mentioned, grew out of my having written on our holdings by black photographers for the Museum’s recent catalogue of its African American collections and my particular interest in Parks’ photography resulted from a 2013 show I organized of Bruce Davidson’s East 100th Street pictures shot in Harlem during the same moment in the late 1960s that Parks was there working on his “Harlem Family” story for Life. I’ve also made it my goal to seek out and acquire work for the collection by a much broader and more diverse group of artists whenever possible, including Dawoud Bey and Zanele Muholi who are active today, as well as earlier work by figures such as Graciela Iturbide, Yasuhiro Ishimoto, and Kamoinge group members, Louis Draper and Anthony Barboza. In addition, I am actively trying to acquire a cohesive group of Civil Rights era photographs, which is something that the MFA has in only very few examples and are becoming harder and harder to find in period prints. We have a relatively limited space to exhibit photographs in our galleries, but when I am able to curate a show like Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott, which enjoyed such a terrific public response, I do realize that there is a serious pent-up demand in our community for seeing strong and sympathetic work that focuses on people’s everyday lives and experiences. I can’t emphasize enough just how encouraging it was to realize that those photographs still spoke so vividly and stimulated so many great conversations among visitors, family members, school group classes, aspiring young photographers, and even individuals coming forward to tell me that, for example, they were the little girl in the photograph seated at the piano on Chicago’s South Side all those many years ago!

JTD: It is no secret that the art world lacks diversity in many ways and that many exhibitions and publications are made from a predominantly white, male, straight vantage point. As a curator, how do you view your role in changing this bias? What are some tangible ways of increasing access for a wider variety of voices?

KH: Yes, the museum world in general is still very lacking in diversity, the progress on that front has been extremely slow, and I’m afraid it’s hard to see that changing any time very soon. I think the same impetus to exhibit work and organize programming that resonates with a much broader range of people will be what ultimately leads to more diverse arts organizations as well – that, of course, and better financial aid to support the advanced degrees such occupations require and higher salaries once people are in those jobs. Nevertheless, my colleagues and I at the MFA are feeling very upbeat about the direction the Museum is going under our brand-new director, Matthew Teitelbaum, who is Canadian-born and came to us from the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. As a contemporary specialist, he is pushing us to expand our thinking about future exhibitions and publications and placing a real emphasis on finding new ways of involving a wider variety of voices beyond the strictly curatorial one that has been our usual model until now. For example, my contemporary colleague, Jen Mergel, is organizing a really innovative show that goes up next week called “Political Intent” which will give “insiders” like me—as well as other members of our larger community beyond the museum—the opportunity to focus on a different piece each week and discuss what to our minds makes our chosen piece “political.” (This is in addition to the actual works of art on the gallery walls, but these regularly changing images will appear on a screen in the gallery and also on social media and a dedicated webpage, including a variety of hyperlinks to other sources and encouraging the public to share their thoughts as well). I’m planning to feature our Lyle Ashton Harris photograph, Miss America (1987-88), because we’ve recently been so inundated with images of athletes draped in flags during the Olympics, that I think this stunning picture of an androgynous black nude, wearing heavily powdered “white-face” and an American flag, is worth revisiting as it touches on many very topical issues of race, gender identity, and changing definitions of beauty.

JTD: You are very involved in your local art community. What role do you think art plays in a community, and what role do you think creating community plays for artists?

KH: I try and stay as involved as possible in the greater Boston arts community and if there were more hours in the day I’d love to do even more. I currently serve on the board of trustees of a small community art school in my neighborhood of Jamaica Plain; I regularly teach classes and give tours to school groups and adults, do portfolio reviews for artists, and crits for students in the many photography programs in the area; I organized A Fragile Balance: Eight New England Photographers for the Magenta Foundation/Flash Forward Festival this last spring; and I’ve just been invited to create an exhibition of emerging young photographers for Boston City Hall in 2017. All these projects really enhance my work life and ultimately make me a better curator, I think, but my hope is that they also strengthen the MFA’s ties to the larger community which does not always feel that this is “their” museum or that it necessarily speaks for them. We are working very hard to change the public’s perception of what a museum’s role will be in the future and I believe that over time we’ll gradually come to be thought of more like town squares or community gathering places where the sharing of art and ideas (and food and drink!) will have an ever-more open, inclusive, and generous feel for all those who wish to take part. At least, I hope that’s true.

Karen Haas at the MFA Boston, 2015.

JTD: What’s next for you as a curator? What projects are on the horizon?

KH: I’ve just helped curate a show of Mexican works from the 1920s and 30s by Edward Weston, Tina Modotti, and Diego Rivera in our Art of the Americas wing that celebrates the MFA’s recent acquisition of a major piece by Frida Kahlo (Dos Mujeres, 1928), the first Kahlo painting to enter a New England museum. And opening on September 3rd will be my exhibition, Imogen Cunningham: In Focus, which I’m very excited about, as it features the major female figure among the American modernist photographers whose groundbreaking seven-decade-long career is surprisingly little known and is striking in its range and variety. I’d also love to continue to organize and jury photography shows outside the MFA and I have at least one book project in my head that I’m hoping will allow me to collaborate with West Coast colleagues and return to working on the 6000+ photographs in the Lane Collection, which was given to the Museum by Trustee Saundra Lane in 2012.