Q&A: Johanna Warwick

By Rafael Soldi | Published on April 13, 2017

Johanna Warwick is a graduate of Massachusetts College of Art and Design MFA Photography 2010, and Ryerson University BFA in photography 2006. She is a British born, Canadian raised photographer now working and living in Baton Rouge, LA where she is an Assistant Professor of Photography at Louisiana State University. She has exhibited in New York, Toronto, Los Angeles and other major cities across North America. She was most recently exhibited in Fresh at Klompching Gallery in Brooklyn NY, and was a selected artist by Lesley A. Martin as part of her Guest Room curating for Der Greif online magazine. She recently had a solo exhibition Monuments to Strangers in Dallas, TX, and has several two-person exhibitions of the work coming up across the United States in 2017.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Johanna! Thank you for being part of our latest exhibition. Let's talk about All That Love Allows. Where were you in your life at this moment and how did this work help you understand your relationship with your family?

Johanna Warwick: I began working on All That Love Allows when I moved to Boston and began grad school at MassArt. It was the first time I had lived a significant distance away from my family, and it gave me the space I needed to really step outside our family dynamics and consider them from a removed space. I began to question my relationship to my mom and her illness, as well as the changing roles of my brothers and I to our parents. I was able to think of the specific narratives I wanted to show and what they could say about our family.

RS: Has your perspective on this work changed overtime?

JW: Definitely. I still really love those photographs, but I think they were very specific to what I was experiencing when I made them. In hindsight, making the work helped me to begin to accept my family, and recognize that everyone always did their best. It may not have been what I always wanted, but it was their best. I've often thought about going back to the series, to continuing it further - but I think they would be very different photographs. The things that I worry about now in our family, are different than back then.

RS: The photographs in Between The Ground and The Sky are not just formal studies of a marble quarry. Can you elaborate on some of the metaphors for mortality and passing that are present here?

JW: Sure. I began this work after wrapping up on All That Love Allows. I was thinking more and more about my parents mortality, but wanted a break from photographing people. I wanted to work in an observational manner, to try and look at death and loss. I came upon the marble quarry through a friend, and after some research learned it was where the marble was coming for veterans graves. After my first trip to the mountain, I was struck by how much the place became a metaphor for loss, not just the material. This beautiful, immense landscape was being hollowed out, changed and broken. I used this research and visual language to hopefully create a feeling of considering mortality.

RS: How did Monuments to Strangers get started? At which point did you notice a connection between the material and the representation of women in the media, and how did you choose to address this?

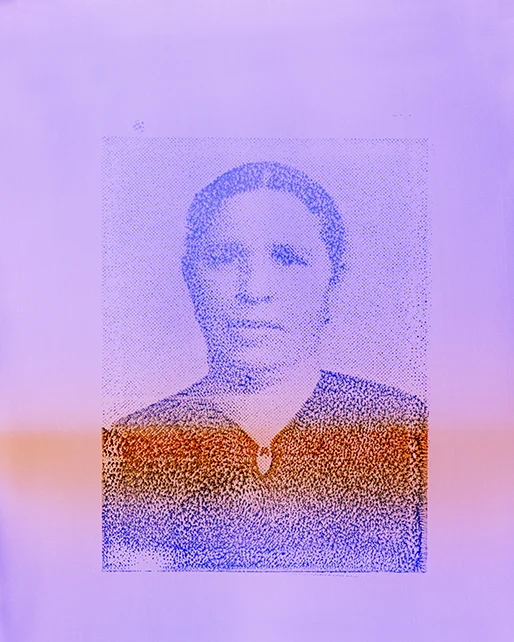

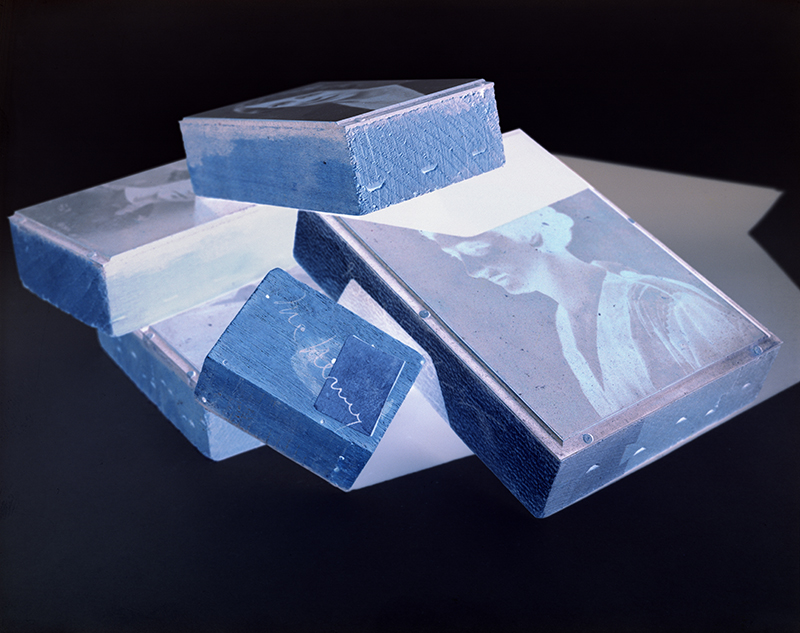

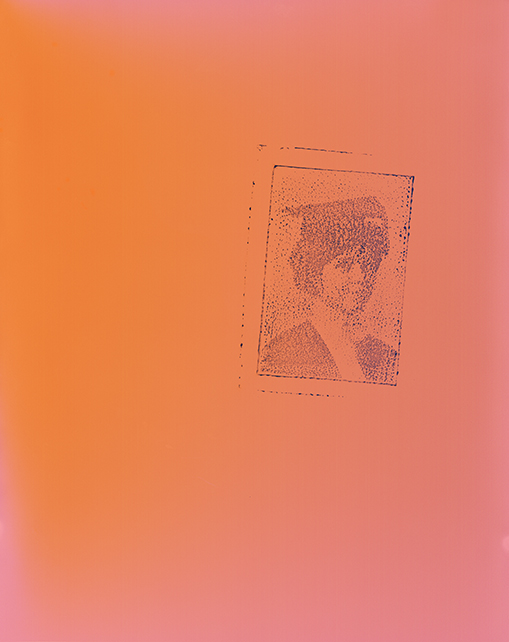

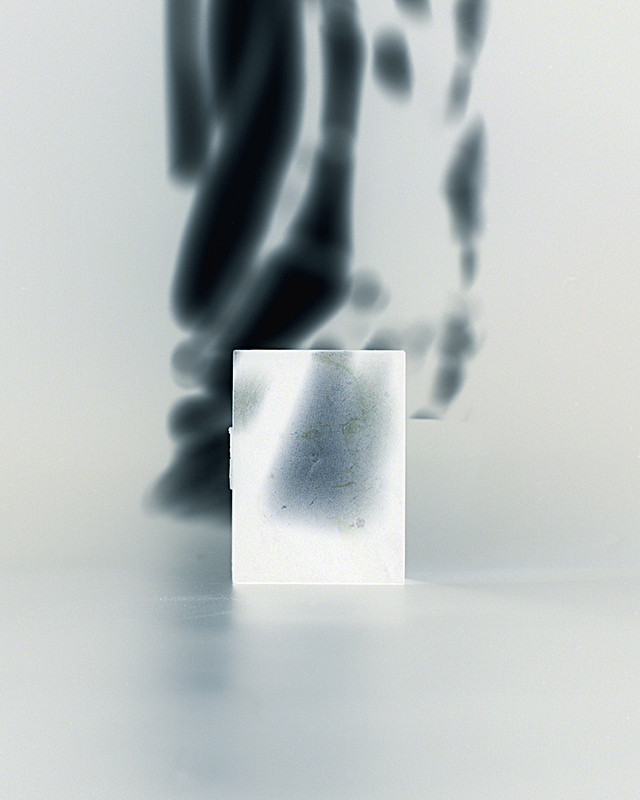

JW: I first began this work while still working at the quarry. I happened to see these little printing blocks lined up on a shelf in an antique store, and was struck by how reminiscent of graves stones they were. I took them home and began to photograph. Like most of my work, I started in a relatively simple place, and then the project took on an entirely new life. I started collecting as many blocks as I could find. In this search, it became overwhelmingly apparent almost all of them were of white men. I don't know who the people are, but these blocks were used in American Daily Newspapers between 1880-1960. I began to really look at representation, and didn't want to just re-present these images of men that had already been celebrated in one way or another. I decided that when I did find women or people of color that I wanted to single them out, to show them in a bigger way than they had been before. To that end, the images of women are all made with a camera-less process, made as singular portraits, and are printed at 32x40". In contrast, I photograph the men often in large groups and print them small. I hope in these decisions when seeing the work it becomes apparent, the under representation in history and my attempt to right that in some way.

RS: Has the current state of our political climate changed the way you relate to this work? Do you feel a different type of kinship with the women in this work, or in any way energized by your "collaboration" with them?

JW: Absolutely! The political climate has definitely pushed me more into the importance of trying to show these women, to try and rebuke the system. I love the idea you brought up of kinship and collaboration with these women. I don't know if I'd really thought of it that way before, but it's a beautiful way to interpret it. I hope I can do right by these anonymous women in our history.

RS: Can you elaborate on some of the techniques you're using to achieve the formal elements in this work?

JW: I think of making work as problem solving. This series has been different for me as it's the first time I've really worked in the studio, and essentially have had to figure out how to photograph the same object over and over again. I will often change the way I'm making the work to reinvent the photos, from studio light, to natural light, to adding in additional objects, to making physical prints of the blocks on film, creating camera-less images of the women. All of the blocks are a negative image, so after I photograph them I have to scan my film and invert the file. This allows you to see the portrait as a positive, while all the space around the block becomes negative. I love how the glow of light and shadow and shift in colors describes these people.

RS: What's next for you?

JW: I'm still continuing to work on Monuments to Strangers, and think I will be for some time (as I keep on the search for women and minorities). I do though miss photographing out in the world and so have begun a new body of work. A year and a half ago I moved to Baton Rouge, and 6 months ago my husband and I bought a home in a previously segregated neighborhood. We are now very much a part of a community that has an incredibly dense history. I've begun to photograph, and hope to eventually create a body of work that can speak to this place.

All images © Johanna Warwick