Q&A: Jennifer Ling Datchuk

By Hamidah Glasgow | February 25, 2021

Organized by Strange Fire Collective (SFC), An Active and Urgent Telling features the work of six contemporary artists working with photography to honor the weight of lived experience through an intersectional lens. Stemming from SFC’s mission, this exhibition centers artists for whom questions of identity deeply affect their relationship to representation. The works included engage with ideas of visibility and invisibility, the reality of lives that exist outside of, or in opposition to, expected and enforced social norms, and the social and political power of speaking one’s truth. Each artist contributes nuance to a redefinition of the commonly understood fabric of difference through an active and urgent telling of their own lived experiences.

Original, in-depth interviews with each exhibiting artist will be posted on www.strangefirecollective.com during the exhibition to illuminate a more thoughtful understanding of the artists and their work. Exhibiting artists include Jennifer Ling Datchuk, Delphine Fawundu, Penny Molesso, Rachelle Mozman Solano, Irene Reece, and Chanell Stone.

Jennifer Ling Datchuk was born in Warren, Ohio, and currently lives and works in San Antonio, Texas. She is an Assistant Professor of Studio Art at Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas. As the child of a Chinese immigrant and grandchild of Russian and Irish immigrants, the family histories of conflict she has inherited are a perpetual source for her work. She captures this conflict by exploring the emotive power of domestic objects and rituals that fix, organize, soothe, and beautify our lives. Trained in ceramics, her works often use a myriad of materials ranging from porcelain to fabric or embroidery. Datchuk holds an MFA in Artisanry from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth and a BFA in Crafts from Kent State University. She has received grants from the Artist Foundation of San Antonio as well as Artpace to research the birthplace of porcelain in Jingdezhen, China. In 2016, she was awarded a residency through the Blue Star Contemporary Art Museum at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin, Germany and was a Black Cube Nomadic Museum Artist Fellow. She completed a residency at the European Ceramic Work Center in the Netherlands in 2017 and was awarded the Emerging Voices Award from the American Craft Council. In 2020, she was named a United States Artist Fellow in Craft.

HG: Thank you for taking the time to chat with me. I saw your work for the first time in Lenscratch and was immediately taken with it. To be more specific, it was the wearables that caught my attention. Tell me about them?

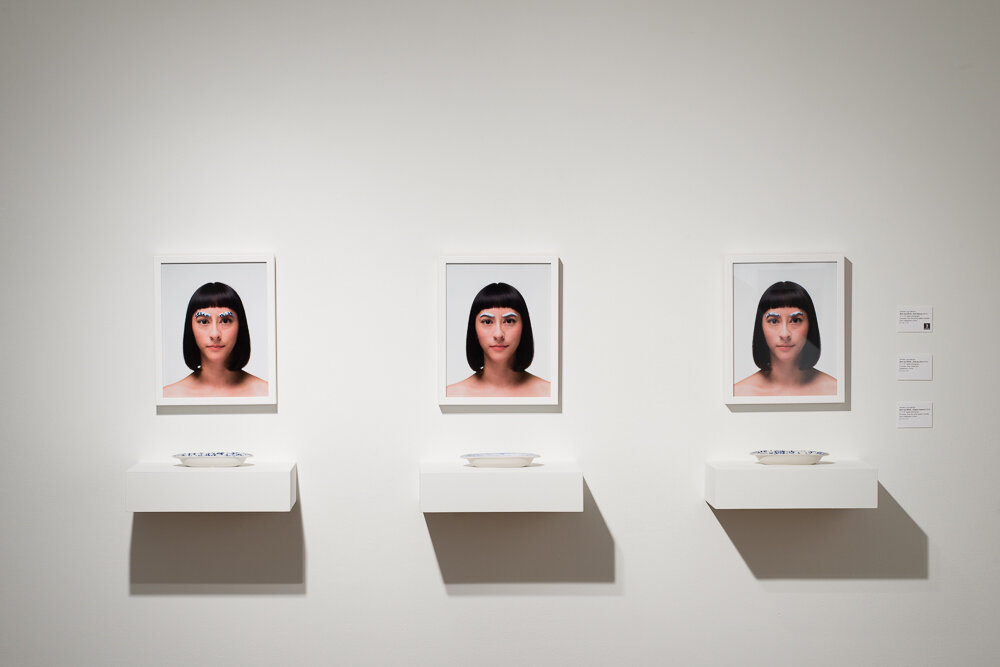

JLD: The wearables are blue and white patterned eyebrows made from porcelain. "Blue and White" is a series of three photographs documenting me wearing the porcelain prosthetics. I was interested in this idea of manufacturing identity and beauty. I wanted to adorn the space above my eyes with porcelain that has been plucked from a beautiful blue and white patterned tray. I am interested in the global migrations of porcelain and blue and white patterns, how they originated in China and traveled from the East to the West, and were copied and appropriated along the way. When I was in Jingdezhen, China doing research in the porcelain capital of the world, I walked into a tattoo shop for makeup. I saw a poster for tattooed eyebrow shapes with thick or thin tails and high or low arches. Each eyebrow styled was named after a Disney princess. This was an aha moment in my practice where I saw beauty standards from the West travel East and shared a similar journey to porcelain.

I perform identity by wearing the porcelain eyebrows. I drew inspiration from the green card and altar photos of my family. They looked stoic and are reflective of my experiences growing up Chinese - to be completely humble and don't show any emotion.

HG: Tell me more about performing identity and how that takes place in your work?

JLD: As someone who is biracial and the daughter of an immigrant, I often have to navigate and understand my own identity between two different families, cultures, traditions, and worlds. I think about what I am allowed to own and claim when I am judged on my appearance and often put in someone's prescribed box. These lived experiences inform what objects, images, and performances I make and how identity can be manufactured and created through adornment and decoration that is appropriated, appreciated, and if cultural reappropriation exists.

HG: You have an interesting family history and artistic background. Please tell me about your trajectory as an artist and how your family's histories influence your work?

JLD: Growing as the daughter of an immigrant, being an artist wasn't an option taught to me. I was supposed to be the dutiful Chinese daughter and become a doctor or lawyer. I very much wanted to be a lawyer and started studying it in school until I took my required art class. I fell in love with it and felt like something switched in my brain.

Looking back, I realize I was surrounded by making my whole life from my grandmother and aunties sewing in the home, the constant cooking, and my grandfather's creative use of cut electrical cords from old appliances to create a net for gourds to grow on. I had a unique experience growing up with my Chinese family in Brooklyn, NY, and my Caucasian family in Warren, Ohio. Each side of my family had a set of things we did and didn't have to do as my brothers and I were seen as too white for my Chinese family and too Chinese for my white family, so we existed in a third culture. I think identity is layered and can be complicated and growing up, and even today, I still get asked, "what are you?". This question has really informed my practice, and I explore this through materials like porcelain, hair, and found objects through object making, photography, and performance.

HG: Please talk more about the differences between your Chinese family and your Russian/Polish/Irish/Caucasian family and how that has influenced your work and worldview.

JLD: These differences are what created the third culture I exist in. I clearly remember waving goodbye to my cousins as they were forced to go to Chinese school on Saturdays. My mother said we didn't have to go, and it was never forced upon us. I think it was because we were half and already "American." The other side of my family culturally celebrated and acknowledged their Slavic Eastern European heritage with food, but they ultimately passed for white and "American." I felt like I had to code-switch between the two to make them more comfortable with me but also to receive love from them. A few years ago, I heard a speech from then-President Barack Obama about how millennials are the most racially diverse of any generation before them. I think about this all the time and how these third culture stories are everywhere but not often represented in mainstream media and art. Everyone just wants to see themselves and their stories reflected back to them in the world.

Girl Boss from Don’t Worry Be Happy, 2019

HG: Is the Girl Boss work from the, Don't Worry Be Happy body of work? I'd like to hear about those pieces and the motivation behind them.

JLD: Don't Worry Be Happy explored the social expectations placed on girls and how this pressure translates into womanhood. I wanted to confront how little girls are taught to be seen, not heard, perpetuating our roles as empty vessels for the desire and fulfillment of men. In Girl Boss, I created the image of a woman with rhinestone barrettes in her hair that sparkle "girl" and "boss" with slip cast figurines. I was seeing Instagram images and tv interviews with a woman wearing barrettes with identifying and empowering labels like "boss," "feminist," and "money," but these words did not express how women still earn less than men, the wage gap still exists, and a lot of these issues are even more out of reach for women of color.

One figurine is from a 1970's hobby mold of an Asian girl with her stereotypical China bob haircut, rice pickers hat, a heavy yoke across her shoulders, a dragon embroidered on her jacket, and she stand barefoot. Her body and identity are fetishized in her labor. The blue and white figurine is a collectible produced most likely in Germany of a white woman wearing a kimono and should yoke with buckets. Her labor is fetishized yet feminine and white-washed.

We still have so much more to do to shatter the bamboo ceiling and climb even higher to break the glass ceiling.

Lucky

HG: This write-up about the Porcelain Power Factory piques my interest; how did you form this endeavor?

The Porcelain Power Factory reclaims the past lives of objects to raise the social awareness of causes that we need to fight for. This new body of feminist, functional works are created by Texas-based Jennifer Ling Datchuk. Motivated by Trump's body-shaming and brags of sexual assault, this work is made to empower women's movements. The functional works are a statement of resistance and feminism and a way to give back.

JLD: Working in clay and the history of ceramics, I am surrounded by a lot of mass-produced objects and slip-cast production molds that probably existed in the realm of kitsch. I found that a lot of these ceramic figurines and objects were perpetuating racist, misogynist, and sexist. If you are what you eat, then what are we with the objects we collect, decorate, and surround ourselves with. I found the boob cup mold at an abandoned ceramic supply store in San Antonio.

I hate these types of sexist and misogynist molds, and I've seen these objects in touristy shops with suntan lines or forms for creamer. I took the mold so no one could use it ever again. It wasn't till I heard Trump's and Billy Bush's conversation that the idea came to create the Pussy Power Cup.

Truth Before Flowers, 2019

Pussy Power Cup

HG: Your series, Truth Before Flowers, also speaks to empowerment and discovery. Materials that in the past have defined gender roles are re-imagined as tools of deconstructing patriarchy. Tell me more about this.

JLD: "Truth Before Flowers" disentangles histories and traumas to find empowerment through objects of womanhood. Porcelain objects inspired by the history of teacups and dinnerware allow me to speak in dualities, especially of fragility and resilience and ultimately the struggle between diversity and the flawless white body. Materials like porcelain and hair have crisscrossed the world and are migrations of identity and have the power to tell stories. In the 60's and 70's, textiles and pottery were considered women's crafts and not art, hobbies taught at community centers, churches, and after-school programs. I often think about how these were taught to women to keep their hands occupied and keep our voices in domestic spaces and out of public spaces. I want to deconstruct established hierarchies of materials and champion the handmade. There is a lot of shame and isolation in our stories, and I am frustrated that we have not overcome more as women. Through pain and perfection, these objects amplify female voices, reconstruct our identities, and celebrate our truths.

An example of this can be seen in my piece "Don't Play Nice," and consists of a small porcelain teacup and saucer. Upon closer inspection, you see the teacup is really a small megaphone decorated with found ceramic decals in floral patterns. I think about how as little girls, children really, we were taught to play nice with tea sets and not taught to yell, scream, shout, and amplify our voices.

HG: Live To Die, seems appropriate for a body of work produced in 2020. From your website:

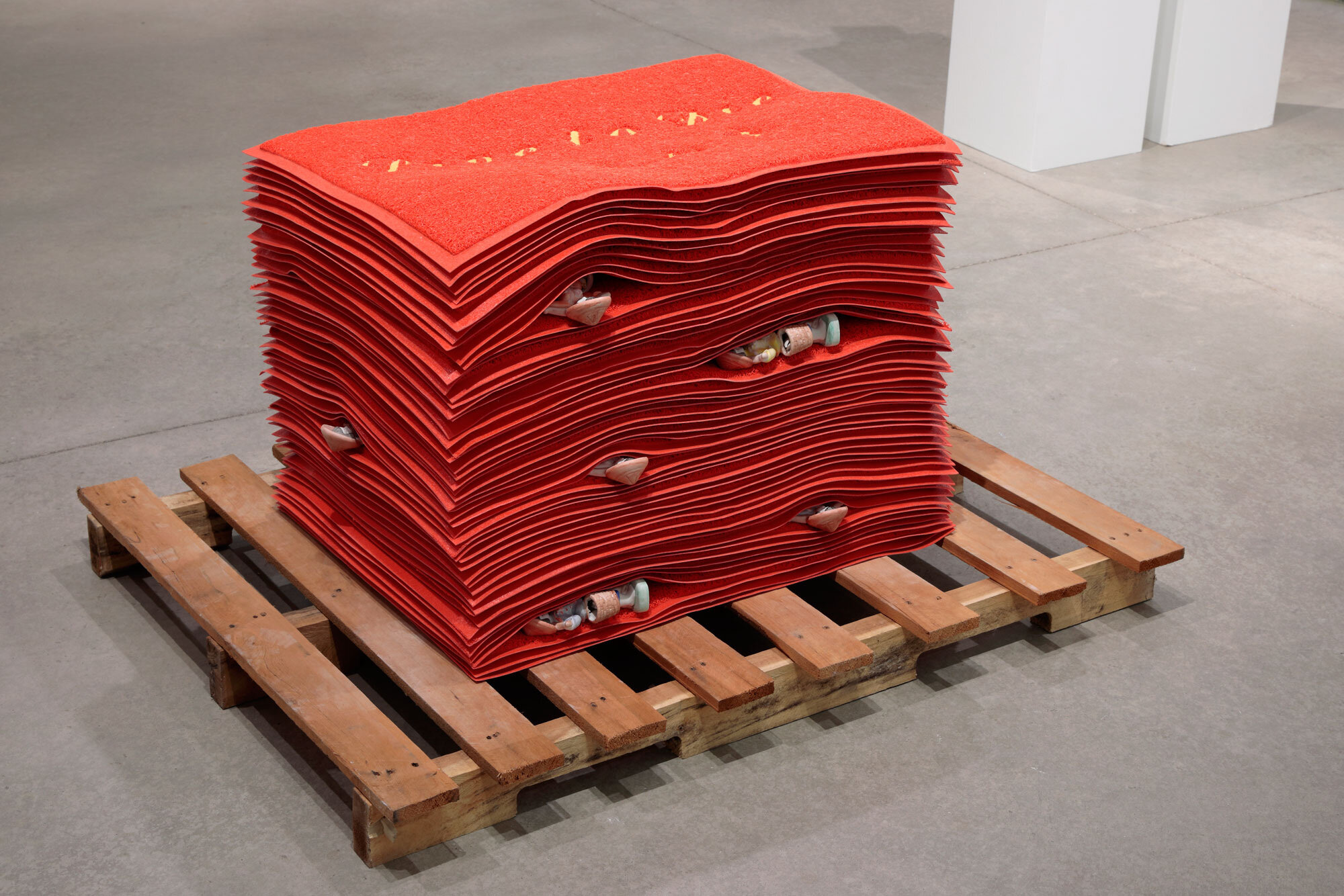

"Red doormats that say "welcome" in Chinese and English are found in front of almost every Chinese restaurant and business all over the world. These mats are markers for crossing thresholds, the objects below our feet that welcome or receive us as we work, spend, desire, and consume. This red is symbolic of good luck and fortune in Chinese culture but synonymous with anger and passion. The pallet rack with the stacks of mats embossed with the phrase "Live to Die," a morality statement found at the bottom of alphabet samplers from the 1800's. This phrase stitched onto linen by the hands of young girls who probably did not fully understand the darkness and futility of these words."

Disrupting the perfect stacks of doormats are golden figurines of a young Asian girl, barefoot, wearing a rice pickers hat, and carrying a heavy load on a shoulder yoke. They become buried under the weight of the mats, hidden and obscured, but we know they are there. Her labor and presence invisible to the objects we so easily order and buy but so much a part of this cycle of consumption and fulfillment.

I often think of the label "Made in China" and how it's associated with cheaply and poorly made objects. What makes their labor and bodies any less than that of American labor? We need to acknowledge and confront the capitalist systems in place that have created an American ruling class that has put profits over people for decades and continually exploit global inequality.

Please tell me more about the use of red, and its meanings, what alphabet samplers were, and the young women that stitched these linens.

JLD: I approach red through its significance and power in my Chinese culture as a symbol of good luck, happiness, and fortune. It's hard for me to see it and not think of a red baseball cap, a hat most likely mass-produced in China to symbolize "American" values and thinking.

Alphabet samplers are woven pieces of fabric that showcased needlework styles like cross-stitch and embroidery. They often included the alphabet, numbers, morality statements, the name of the person creating it, date, and decorative motifs. In the 18th and 19th centuries, there were schools devoted to teaching young girls the patience of individual stitches to learn important skills in running a future household. They are considered the first form of education for females in the United States, and we know now that these schools were most likely only for affluent families. I've been researching the morality clauses found in these samplers, and one that sticks with me was made by a young girl named Fanny Hills and at age 9 in 1848.

She stitched "Fidelity and Truth is the Foundation of Justice," and I wonder if she ever knew the power of these words and how over 100 years later, we are still searching for justice.

HG: The exhibition, An Active and Urgent Telling, delves into lived experience and the importance of the narrative from a first-person perspective. How do you see your work fitting into that framework?

JLD: The title "An Active and Urgent Telling" to me is a call to action. As I type this, violence and racism against Asian Americans are on the rise and exacerbated by the continued rhetoric around the pandemic. Often this community has stayed silent, and our stories are not depicted, our histories are not taught in schools, and we have contributed so much to the building of America. I bring these histories to my work and the stories of the women in my family whose stories were not passed down because they were not sons, and their stories did not matter.

I use the power of the image and the porcelain object to construct and present these layered and complicated stories. Porcelain as the material and metaphor for globalization, commodification, and appropriation but speaks of dualities like fragility and resilience.

HG: Thank you for your time and for sharing your work!

Live To Die, 2020

All images © Jennifer Ling Datchuk