Q&A: Janie Stamm

By Jess T. Dugan | September 5, 2019

Janie Stamm was born and raised on the edge of the Everglades in Broward County, Florida. She is a craft-based artist currently residing on the western banks of the Mississippi River in Saint Louis, Missouri. Her work focuses on preserving Florida’s environmental and Queer history in the face of climate change. She uses a craft-based practice to tell these stories.

In the spring of 2019, Janie received an MFA in Visual Art from Washington University in Saint Louis. She was most recently the recipient of the 2019 John T. Milliken Foreign Travel Graduate Award, a Regional Arts Commission grant, a Dubinsky Scholarship to study at the Fine Arts Work Center, and the Frida Kahlo Creative Arts Award from Washington University in St. Louis. Her work was featured on the cover of the December 2016 issue of Poetry magazine. Janie has shown work throughout the country including Los Angeles, Atlanta, Chicago, and throughout the Saint Louis regional area. After finishing up a residency at ACRE in Wisconsin, Janie will be an artist-in-residence at the Cite Internationale des Arts in Paris for the last few months of 2019.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Janie! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. Let’s start at the beginning – how did you discover art making, and what was your path to getting to where you are today?

Janie Stamm: Me and making go way back. We first met when I was just a little kid figuring out my fine motor skills. I don’t exactly remember the first time I picked up a crayon or marker, but I do know that it was love at first scribble. My parents quickly caught on that I had a knack for making art and have always encouraged me to keep creating.

One of the things that brought me pure joy when I was a tiny baby artist was going over to my grandma’s house. She is a lifelong crafter and was my first art teacher. I knew that every time I went to her apartment we would be making something amazing like sewing dresses, hot glueing gems onto old AOL cd’s she would get in the mail, and making crepe paper gardens. She gave me the skills that are at the core of the work that I am making today.

In 2011 I graduated from Savannah College of Art and design with a BFA in both printmaking and animation. After school, I moved to Chicago where I worked for a couple of different print shops as an assistant. While I was living in Chicago, I went through a three-year art drought. I was suffering from a mix of artist block, depression, and anxiety. I struggled to make work. This (art making) was a thing I had my whole life, something that brought me immense amounts of pleasure, and the loss of it was devastating. I spent many days feeling overwhelmed by the fact the I wasn't able to make and couldn't muster the energy to even try because I was so scared of failing.

Daily Snake Drawing

But then one day in late 2015 I had a break through.

I started a daily drawing project. For a full year I drew a snake every single day and posted it to social media. The idea of posting it onto the internet forced me to hold myself accountable, knowing people were possibly watching and following what I was posting. I filled up two sketchbooks with 366 different snakes. The daily drawing project allowed me to re-introduce myself to making art. It was slow-paced, but the exact therapy that I needed. My little snake drawings gave me the confidence to finally apply to grad school, something that I had been dreaming about since I finished at SCAD.

This past spring I graduated with my MFA in visual art from Washington University in St. Louis. Going to grad school was one of the best decisions I've ever made in my life. It opened my eyes to the possibilities of what art can be an allowed me to discover myself as an artist.

Dorothy

JTD: You work in a wide variety of media, including fiber, sculpture, installation, and printmaking. What is your process for developing a piece from idea to object? Do some ideas call for specific physical manifestations more than others?

JS: I'm very much all over the place when it comes to creating my art. I never really sketch anything out because I've come to find that when I do draw out my ideas I tend to never revisit them. It's almost like they die in the sketchbook. So now I just work intuitively and let my materials tell me what they want to be. I go in with a slight game plan, just enough to have a rough idea of possibly something I may be might make. Really, it's just a little thought in my head that I hope turns into something that can be considered art.

I used to be a really big control freak when it came to my art. I set a million different rules of what my art could and couldn't be instead of allowing it the space and freedom it needed to become what it wanted. I limited myself to just the things I was trained in while in undergrad, and never let myself venture out of my tiny boxes. While in grad school, I realized the importance of being open to different processes, especially things that I had written off entirely, like my love of crafting. Now I'm a changed artist! My favorite thing to do is to dabble in as many different making modes as possible. At the moment, I am rather smitten with craft-based techniques such as embroidery and papier-mâché.

Birth

JTD: Tell me more about the element of craft in your work. How did this come to be an important aspect of your practice?

JS: Craft has always been a part of my life, but I’m ashamed to say that I never viewed it as ART until I got to grad school. For years, I disregarded the medium as merely a hobby or a pastime instead of fine art, but for some reason, while in grad school, something switched in my brain. I realized that craft is ART and that the things my grandma taught me are just as important as learning how to paint, sculpt, or write.

After realizing the obvious, I welcomed craft back into my practice with arms wide open. Honestly, it has changed my relationship with my art. I has allowed me to truly enjoy everything I make now so deeply. I think that is largely because my grandma poured her heart and soul into giving me the knowledge of how to craft with love.

There is a certain familiarity that comes with craft-based techniques that is very relatable to a lot of people. It’s nostalgic and comfortable because crafting is often the way kids are introduced to art and art making.

JTD: In your work, you explore the idea of loss, although through two channels: the loss of queer communities and spaces and the loss of places and cultures due to climate change. How did these two interests develop and become a significant part of your practice? Do you feel that they overlap, or are they two parallel threads you are exploring simultaneously?

JS: I’m originally from South Florida. I was born on the island of Miami Beach and raised on the edge of the Everglades. Over the course of my life, I will watch as sea levels rise and begin to cover the place that shaped me into the person that I am today. I will watch as my personal history will drown alongside the histories of queer folks and nature in the State of Florida. Loss is something that I am preparing for and dealing with at the same time. At times, it feels like I am in this perpetual state of mourning, but for something that is slowly going away.

The two definitely reflect each other. The way we treat our environment (that includes wilderness and urban landscapes) mirrors how queer people and queer space is treated. Both are often forgotten about and society doesn't pay attention until it is too late. I feel like it takes something fully disappearing like an endangered species or the oldest gay bar in town for people to be like “Oh, wait a minute…maybe we should have done something to save that.” I’m tired of waiting until things are gone. I want to celebrate them now, while they are still here.

Beach Notes II

JTD: It’s an interesting moment for queerness; simultaneous with (and perhaps directly in response to) a rise in mainstream visibility, we are losing long-held queer spaces, as you mentioned, and, in some cases, communities. What is your reaction to this shift? And in what ways has it affected, or inspired, your work?

JS: This is something I have such mixed feelings about.

It makes me so happy to be living in a time where I see queer people on TV, in museums, and the faces of various campaigns. I love that the world is finally starting to see queer folks; I mean, we have always existed, it’s just now that we are finally getting the attention that we deserve!

I question whether or not society’s consumption of queer culture is beneficial for the queer community. Sacred places like neighborhoods, dance clubs, and bars, where queer folks live and socialize with one another outside of the heteronormative world, are becoming few and far between. Trans people, specifically trans women of color, are under a constant threat violence. It saddens me that when I look around, I don't see the people who claim to support us fighting for us. Those consuming queer culture need to stand alongside us when we need help instead of just being around to party with us during Pride.

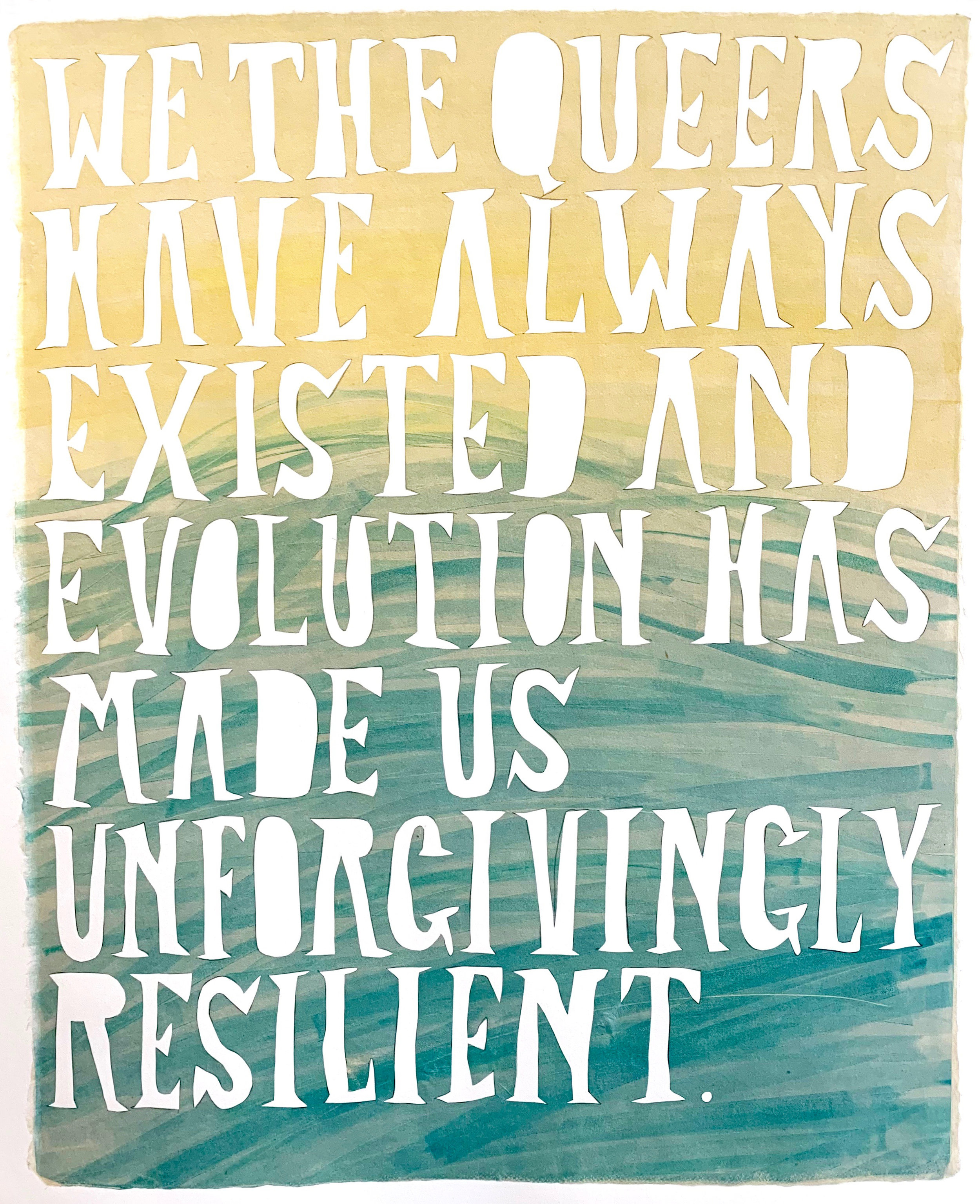

I use my art as a platform to educate people on queer existence. Nearly every single piece of art I make is discussing queerness; whether it’s queer history, current queer life, or what a queer future might look like. Visibility is one of the cornerstones of my work. I’m a firm believer in the idea of how good it feels to see yourself represented in something. I can’t help but wonder what my life would have been like if I had seen a queer person growing up. Would I have come out earlier (just for reference, I didn’t come out until I was 24)? I recently worked a pride event where I was blown away with how many young queer kids I saw walking around with their parents. These little kids know exactly who they are and nobody is questioning their existence.

If anything, I feel like this is a strong moment for queer art. It’s a time where people are starting to pay attention to what is going on in the queer world. It was most recently the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, a pivotal moment in LGBTQIA history where the gay rights movement is said to have begun thanks to the actions of Marsha P. Johnson and other queer folks who were at Stonewall. Queer folks are finally being given space in institutions that once wouldn't show our work but now want us to take up real estate in their galleries. But, bouncing back to my uncertainties, I just hope this acknowledgment and consumption of queer culture is genuine and long-lasting as opposed to a temporary fetish.

June 12, 2016

JTD: Your work is deeply connected to history, but also pulls from the present. Tell me about the memorial quilt you made in response to the massacre at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando. How did it come about, and what was its final form?

JS: I was staying with my parents in South Florida when the pulse nightclub shooting happened. I was up late and remember watching the shooting unfold online. At first it was a shooting at a Florida nightclub, then it was casualty count, and then it became a shooting at a gay nightclub on a night dedicated to Latinx folks. I remember exactly where I was, what I was doing and what I was looking at when I heard the news that 49 people were murdered at a gay club in Florida.

A week after the shooting I was driving to Chicago (where I was living at the time) with my dad and we stopped in Orlando to see the memorial. I cried the entire time I was there. It was a devastating to thing to see. I’ll never forget the heaping piles of colorful flowers surrounding the names and photos of the people who were murdered. I’ve thought about Pulse every single day since the shooting.

June 12, 2016 (detail)

A year and a half after the shooting I began to think about making a piece of art talking about what happened. I wanted to make something that could serve as an object designed for healing. I decided to make a memorial quilt. The piece was largely inspired by the epic NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, a community created work of art that memorializes those who have died of AIDS through the act of quilting. The AIDS quilt serves as a documentation of life and I wanted to bring that essence into my quit.

In the Spring of 2019, thanks in part to a grant from the Regional Arts Commission of St. Louis, I finished my most important work of art to date: an 8 foot by 8 foot, hand-stitched quilt that serves as a memorial to the 49 queer folks who were killed at Pulse. The quilt is constructed of bright colored felt, shimmering seed beads, and rainbow yarn tassels. While I was making it, I was very intentional not to get frustrated during the process. I wanted to channel as much positive energy as I could into making a piece out of love and mourning.

June 12, 2016 (detail)

JTD: Where do you draw inspiration? What are some things you’re currently looking at or thinking about?

JS: I pull inspiration from nearly everything that surrounds me! I feel like anytime I go anywhere, like a park or even to an antique store, I absorb a ton of visual information. Over time that information seeps into my hands and then into my work.

Currently my eye has been focused on a few specific things: souvenirs from Florida, queerness/queer community, animals, and folk art. I live for anything campy, kitschy, and tacky. I try to keep my art full of humor, incorporating things that are nostalgic and remind people of childhood.

JTD: What are you currently working on, and what’s on the horizon for you as an artist?

JS: At this very moment I am getting ready to go to Paris where I will be an artist in residence at the Cité Internationale des Arts for two months. While I'm there, I will be researching Paris’ LGBTQ history with a specific focus on underground lesbian culture. I plan on making a series of embroidered vests that will tell the stories of different places and people who have shaped Parisian lesbian life into what it is today.

After I return from Paris, I plan on working on some more personal pieces using Floridian citrus as a metaphor to discuss queer sexuality and identity.

All images © Janie Stamm