Q&A: James Bouché

By Rafael Soldi | May 14, 2020

James Bouché (b. 1990) is an artist living and working in Brooklyn, NY. He graduated from MICA in 2012 with a BFA in Printmaking. Recent exhibitions include Family History Center (Baltimore, MD), Dimensional Reflections (Baltimore, MD), Implicit Dimensions (Richmond, VA), and On Human Limits (New York, NY).

Rafael Soldi: Hi James, thanks for chatting with us. Where are you writing from? What’s the environment there like right now?

James Bouché: I’m writing from Brooklyn, NY. My partner and I moved here from Baltimore at the beginning of this year (lmao perfect timing, I know). For the most part, everyone in our neighborhood has been staying indoors and the vibe is pretty calm. Very thankful to live near a grocery store that’s been well stocked. I’ve been able to settle in and start some projects while we’re stuck in doors but I’m excited to explore the area more once we can be outside again.

RS: Let’s start with broad strokes, because we’re going to get into some of these themes more in depth later. Where do you come from, how did you get to art school, and how does your upbringing inform your work?

JB: I was born and raised in San Diego, CA, but moved to Chesapeake, VA for the latter end of middle school and high school. My father and my grandfather were in the Navy and although we didn't move often, I spent a lot of time on military bases. My dad would show us the various aircraft carriers, amphibious ships, and submarines he was stationed on. I knew pretty early on that military life wasn't for me, but growing up around such an ordered and utilitarian environment had a lasting impression.

Around when I was seven years old, my family joined the Mormon Church. I don't remember what the catalyst was, considering we weren’t particularly religious before that, but it unfortunately became one of the defining characteristics of my childhood. I guess there are a lot of obvious connections between military life and Mormonism; a clear path with strict moral guidelines, symbolic ceremonies, and a flat definition of right and wrong. Though during these experiences I had a tendency to balance that side of my life with slightly more poetic interests like competitive figure skating or signing with a deaf choir. I wouldn't describe myself as a theatrical person, but I definitely appreciated a little drama.

Like most young artists, I loved to draw and I was accepted to an arts magnet high school that exposed me to traditional printmaking techniques and photography. Most of my classmates went off to study art in college and when I was visiting MICA I fell in love with Baltimore.

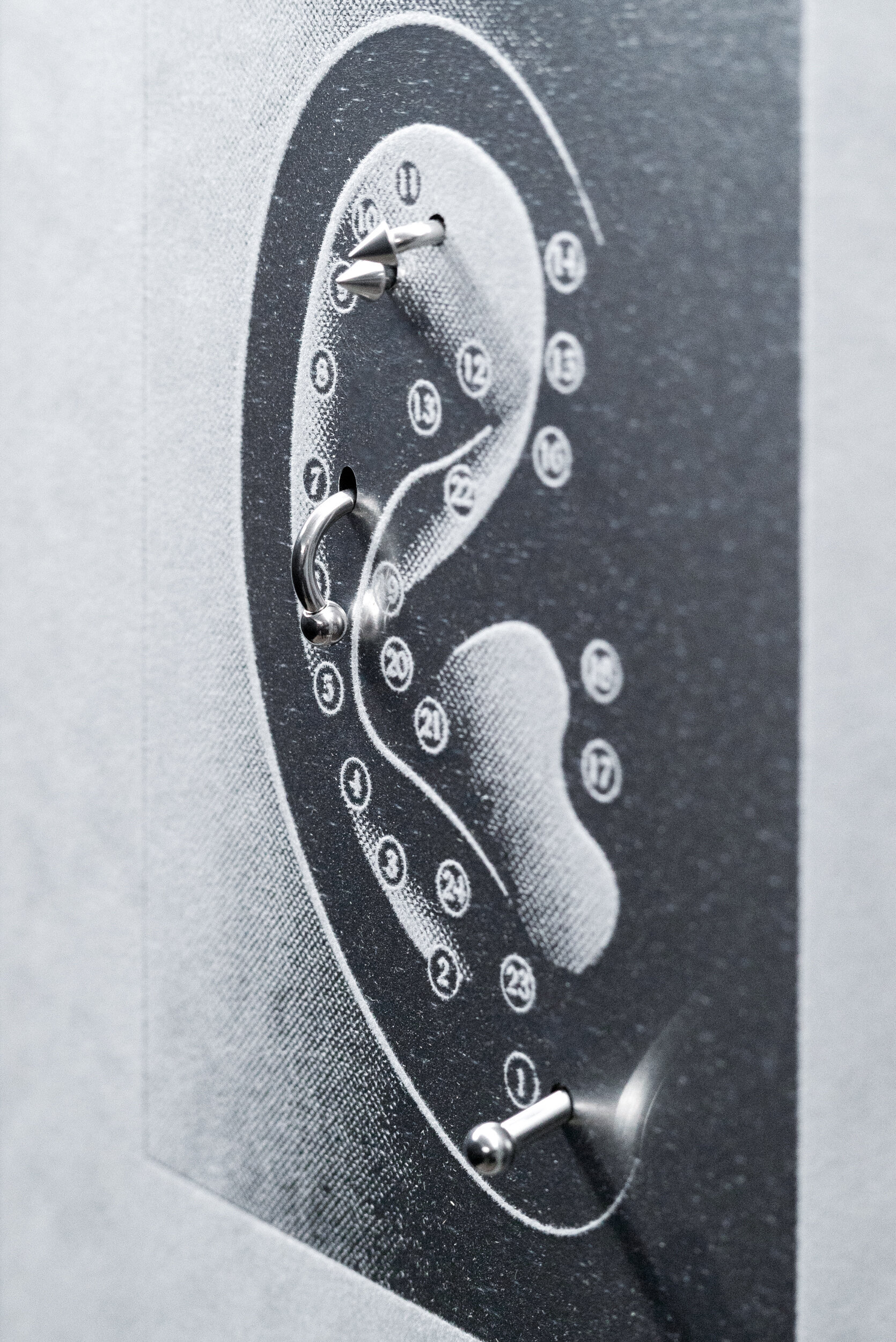

I Buy Myself Roses From Safeway, felt, wood, metal hardware, paint, zipper, 16x20in, 2017 © James Bouché

RS: So you become a printmaker at MICA, but your work is hardly ever representative of straight-forward printmaking techniques. Can you talk about what drives your interest in material and process experimentation?

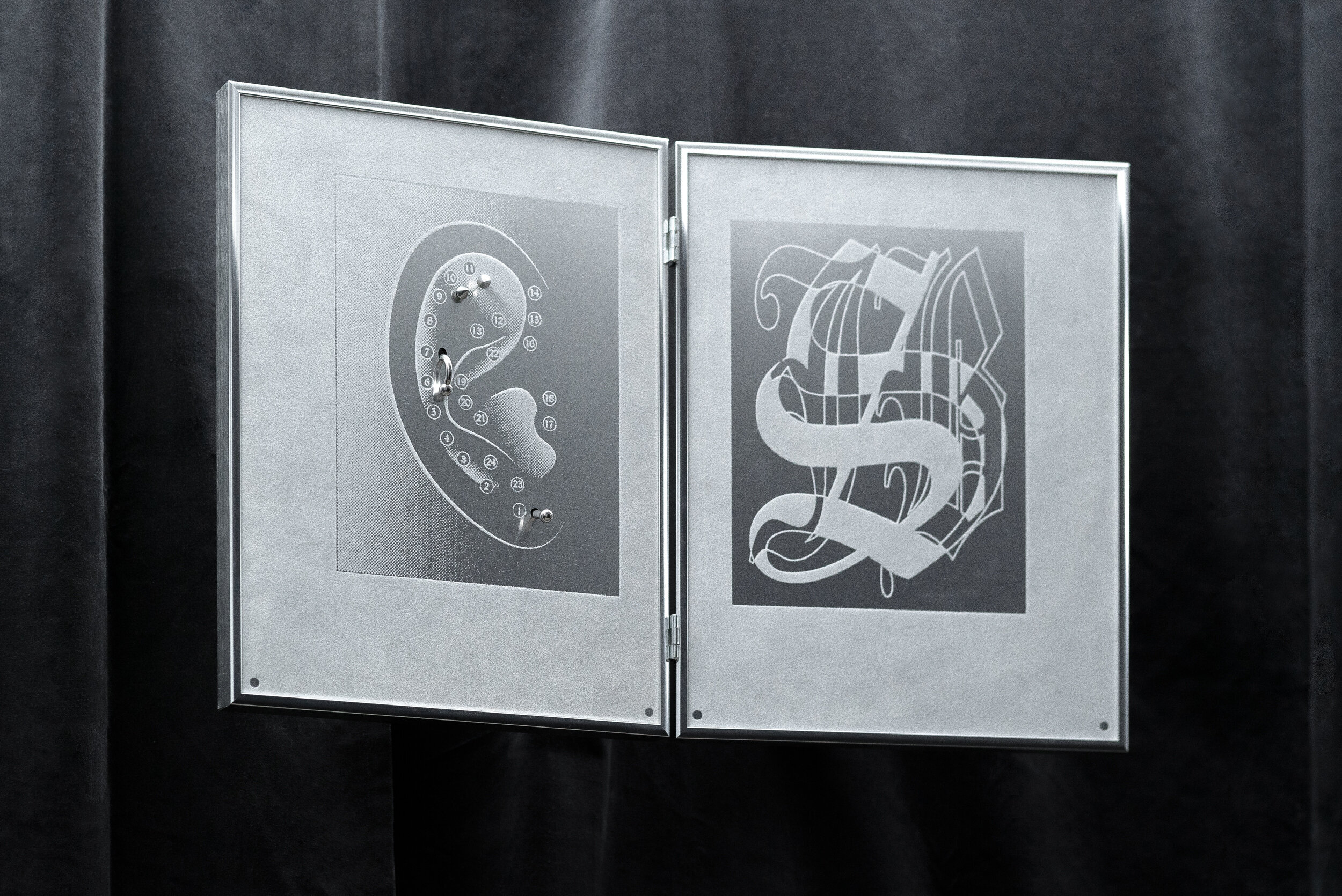

JB: While I was in college I was very much a "Printmaker" and almost exclusively made traditional prints, hoping to one day be a master printer. Every new print was centered around practicing and mastering a different technique in either lithography or screen printing. It wasn't until the end of my senior year that I started thinking more about the content of my work, its context and my rationale for printing by hand. After graduating I continued to make a few prints here and there but I realized there are so many other materials and processes that could inform the content of my work better and more fully than traditional print media. I think I still approach new projects like I would a print. Things are layered, planned out beforehand, and usually labor intense with a strong dedication to craft. Now, I only make a print when I think it makes the most sense conceptually. The work I made for my most recent installation, "Family History Center," could only be made by screen printing. Without getting too technical, I printed an enamel based ink onto aluminum panels, and while the ink was still wet, I flocked it with powdered velvet. Even though it had to be printed by hand, the final result doesn't resemble what most people would consider a standard screen print. I really like trying to find the balance between wondering how a piece was made and being content with not knowing because the content keeps you occupied.

RS: In your exhibition “The Holy Ghost Goes To Bed At Midnight” you mention that the work is “an apology for my participation as a child in the practice of baptism for the dead.” Can you share a bit about this practice and how you’ve chosen to address it? It seems like you’re hesitant to point the finger at the church, but rather take the burden on yourself for your actions as a child.

JB: So, within the Mormon faith, in order to get into one of the kingdoms of heaven you have to be baptized in the church. This includes people who have already passed away who didn’t have the opportunity in life to convert. Because of that, a cornerstone of the church is the practice of baptisms for the dead. Worthy members enter the temple, bringing names of ancestors with them (or be given names at random), and they are baptized as proxies for the deceased. There's been a lot of controversy and tension between Mormons and the Jewish community the past few decades with baptizing the names of Holocaust victims.

Mormon members can start performing this practice at 12 years old and it’s thought of as a rite of passage. Before I was old enough to start questioning my faith in the church, I went to the temple a few times and was baptized for people I did not know. Now that I'm older and have had a chance to reflect, I do feel a guilt for having participated in this practice of involuntarily bringing people (so to speak) into a faith, adding them to the church’s numbers and records.

"The Holy Ghost Goes to Bed at Midnight" was me trying to recreate the feeling of being in an empty church at night—trespassing in a hollow space, now devoid of people and doctrine. I thought of the installation as a collective piece rather than a showing of individual works. The defining changes to the gallery, the custom chair railing, felt wainscoting and three diffused hanging lights that made the room uniformly dim might initially go unnoticed. I wanted viewers to feel like they were walking through a memory or a dream. In some ways I wanted it to be a reflection of my experiences but also a way to process and articulate this personal guilt more than pointing a finger at the church.

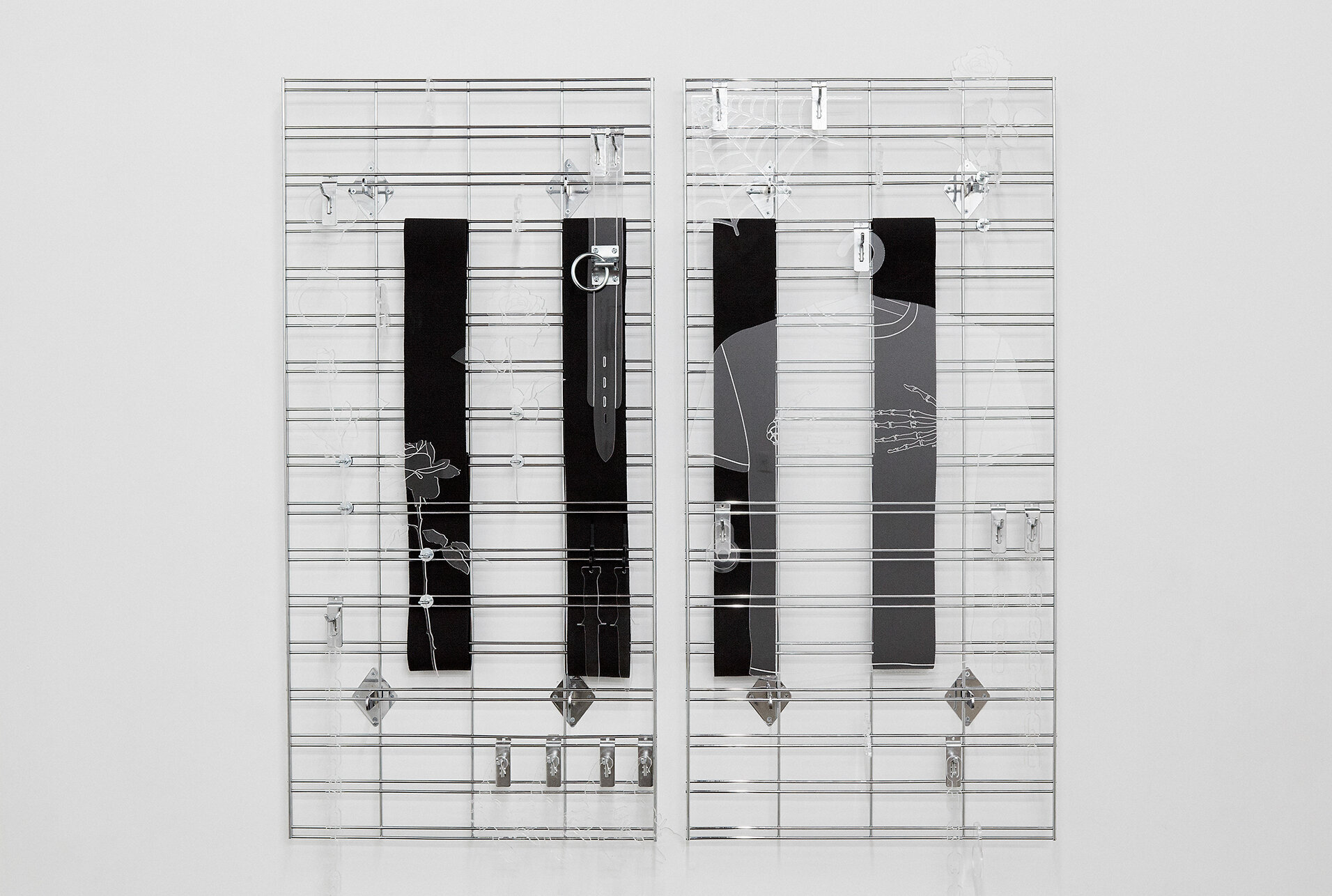

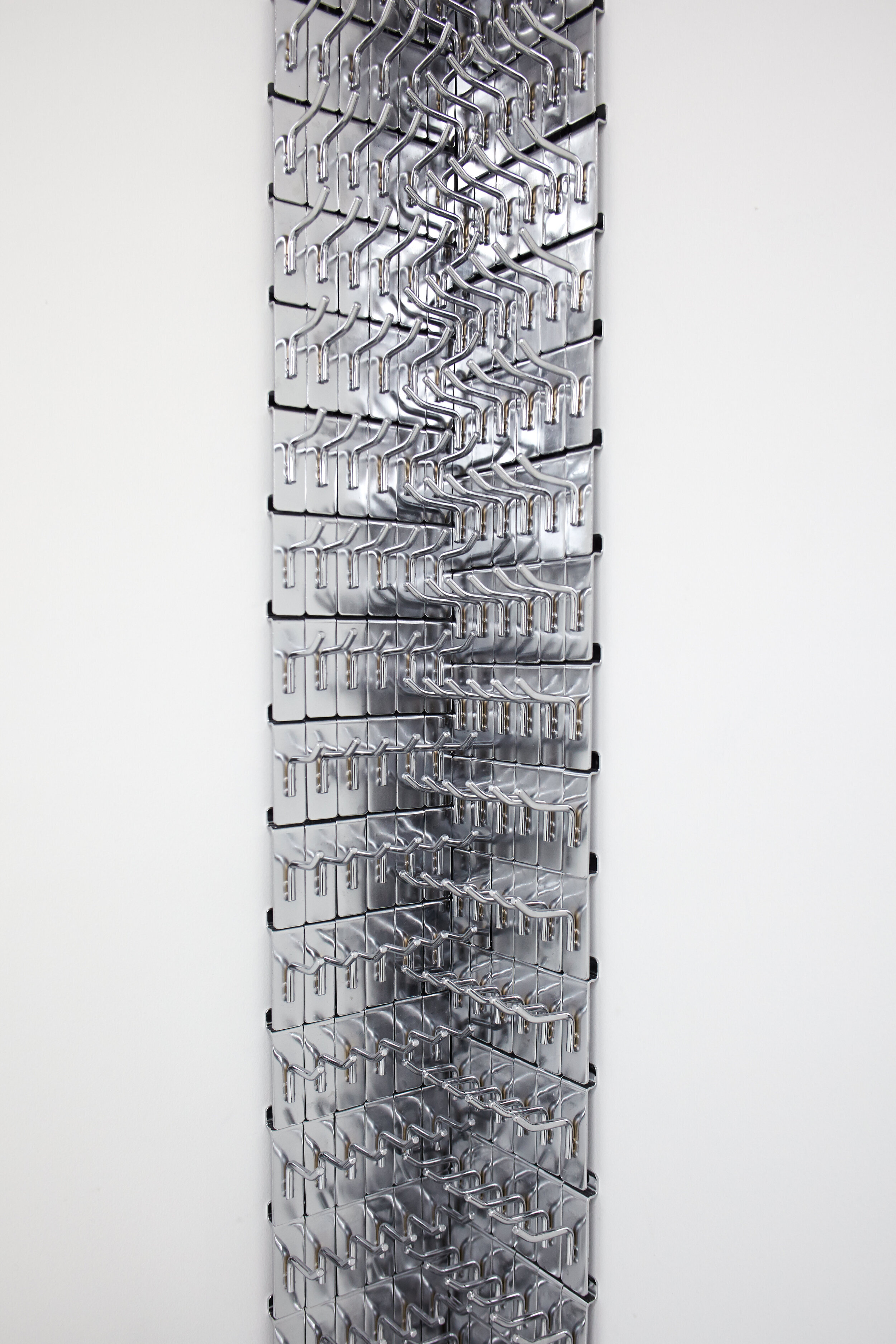

In Smoke, CNC routed acrylic, bike hooks, approx 90x36 in each, 2019. From Transparencies.

We’ve Met Once Before But It Was Just A Dream, CNC routed acrylic, LED lights, galvanized steel, hardware, 72x72x36in, 2018. From Transparencies.

RS: Around this time—starting with “Holy Ghost”—we begin to see the outline of a curtain or flowing veil, which goes on to become a recurring trope in your work. It begins as a supporting element in your installations and then it becomes a primary subject in “Transparencies.”

JB: My use of the curtain imagery started with the "Holy Ghost" installation as flat wall decals representing a ceremonial veil you’d pass through in the temple. The veil symbolizes a physical place where the line between earth and the afterlife is thin. That installation was the first time I really started making work that was heavy and personal to me and I felt the need to start balancing my introspective installations with more simple representations of beautiful and poetic moments. Sometimes it's nice to be able to just visually enjoy something and not feel the need to delve into childhood traumas hahaha. I can be a little more playful with material that way as well. The most recent curtains I made were out of a grey tinted acrylic that I CNC routed. When hung in a window, they're just visible enough to be noticed and appreciated but aren't really functional objects. I love this in between state of the material, the function and idea of the veil itself. But maybe there's just something so nice about fabric blowing in the wind, ya know?

RS: Are titles important to you?

JB: Titles have become increasingly important to me as I get older, but whether or not they get updated on my website is a different story haha. They're an entry point to the work, especially for the pieces that are more specific to my childhood and are a little harder for the general public to approach. I like to give the viewer just enough clues to dig deeper, but only if they'd like to. It's like a choose-just-how-deep-you-want-to-go approach. I spend a lot of time thinking about how my installations interconnect but if someone just wants to appreciate them at face value it's totally fine with me. The Mormon subject matter I've been working with the past couple years is, by nature, kinda mysterious to the general public and I try to make sure it still feels approachable and that people are able to connect with the work in their own way.

RS: Tell me about your recent exhibition “The Family History Center”. What was it about, where did it take place, and how could viewers experience it?

JB: I thought of "Family History Center" as a companion/second part to "The Holy Ghost Goes to Bed at Midnight''. The first installation was meant to be this lingering and sometimes romanticized memory, while FHC is the cold bureaucratic side of a modern religious institution. A major cornerstone of the Mormon faith is being sealed for eternity to worthy members of your family. Through genealogy work, names can be found for baptisms for the dead allowing the deceased to be sealed to living relatives. There’s a genealogical research and storage facility in Utah named Granite Mountain Records Vault, owned by the church, that collects information for members and nonmembers alike. I tried to replicate some of those parameters by installing the show at a 10x20’ storage unit in Baltimore. It was open to the public by appointment only with me guiding them through the space. It's a show about skeletons in every family's closet and considering whether you may be a weak link in the family chain.

RS: There’s a very specific aesthetic language to your work that can be read in different ways. Where does that language—piercings, chains, buckles, straps, hardware—come from?

JB: While there are a few influences for this visual language in my work, funny enough, early 2000’s Hot Topic plays a big role. When making art about my childhood, it made sense to me to incorporate the aesthetics I was interested in at the time. Being an aspiring goth child in a conservative household, I wasn’t allowed to purchase the more extreme clothing accessories I wanted so I had to improvise with things I could purchase at the hardware store. Chains and studs are very much tied to my first outward display of defiance. A simple piercing in the ear of a cis male Mormon immediately tells other members that they are questioning their faith. Within the first week of college I went to a mall kiosk and had my ears pierced. When I went home for fall break that year I didn’t need to say anything to church members and they didn’t ask if I was attending service in Baltimore.

RS: How do you feel about people who may read it as an aesthetic borrowed from the BDSM community?

JB: This is something I’ve thought about quite a bit since being part of an installation titled “xXx” with two then-Baltimore-based artists Laura Judkis and Colin Schappi. Although I’m not especially “kinky” in my home life, I think there is a lot of shared ground between the kink and queer communities at large. Both have a desire/need to deviate from the concept of a patriarchal “Nuclear Family” and are able to define for themselves what types of interpersonal and family dynamics can be created. I think that’s why the kink aesthetic has become so engrained in queer culture. It is a visual representation of letting go of society’s heteronormative roles. I’m not suggesting a viewer would be able to get all that just from looking at my work, but I hope no one from the kink community feels as if I’ve appropriated their culture.

RS: What’s next for you?

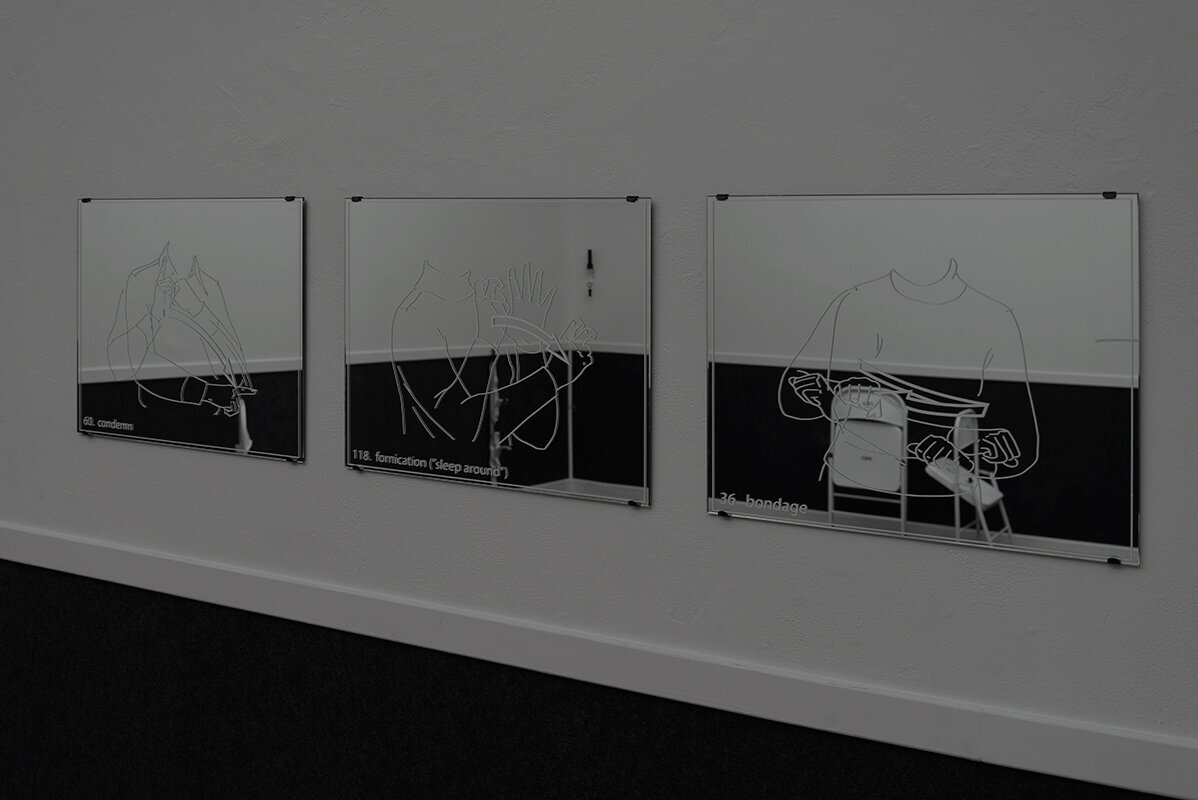

JB: I’m currently planning a couple installations to try and churn out this year. One of them retells the Kiss of Judas as a little gay kiss in the woods and the other deals with the traumas and toxic atmosphere of a cis male locker room. They’ll be similar to “Family History Center'' in that I’m trying to install them in alternative spaces outside of a traditional gallery context. I think the setting of a show can be a powerful tool to carry a message and further inform the work. I’ve also been experimenting with the more functional side of my art, working on some small home good designs and most recently starting to work for a New York based furniture designer, Asa Pingree.

All images © James Bouché