Q&A: hector rene membreno-canales

By Jess T. Dugan | August 3, 2017

Hector Rene Membreno-Canales was born in San Pedro Sula, Honduras and grew up in Allentown Pennsylvania. After serving in Iraq, Hector used the G.I. Bill to move to New York City and study photography at the School of Visual Arts (SVA). While at SVA Hector interned at the Museum of Modern Art, Magnum Foundation, Hank Willis Thomas Studio and Stephen Mallon Films. He was later invited to study Public Affairs & Journalism at the Dept. of Defense Information School, Fort Meade, Md.

Hector's work has been featured in The New York Times, L’Oeil de la Photographie, CNN and The New Republic. He is currently an MFA candidate in the Dept. of Art and Art History at Hunter College, City University of New York.

Jess T. Dugan: Let’s start at the beginning. What inspired you to be an artist and what led you specifically to photography?

Hector Rene: I bought a camera just before leaving for Iraq. I had no intention of making art nor did I have much training or understanding of how images worked. I brought a camera because I wanted to remember the experience. I didn’t want to miss a single moment from my time overseas. Taking photos was cathartic. I photographed everything, everyone, and everywhere. I came home with hundreds of pictures, and with the help of a former photo instructor, I put together a portfolio to apply to college.

JTD: Tell me about your series Hegemony or Survival. How did you begin working on this series, and what was your motivation for gleaning narratives and aesthetics from art historical work?

HR: I am interested in art’s ability to look at our past, present, and future in a single image. While studying photography and media at the School of Visual Arts, I met several other Iraq/Afghanistan veterans who were too using the GI Bill for college. I became interested in Art History broadly, especially in the institutional powers that commissioned and acquired works of art, e.g., the Church (Michelangelo), the Crown (Velázques), the Court (Rembrandt), the State (William Hogarth), and Dutch Tradesmen (Van Beyeren). I shared my interests and ideas with other veterans and we viewed this collective history through our personal lens.

The same institutions that collected the greatest works of art had similar interests in projecting power by declaring war. Similarly, justifications for war included religious, political, and economic resources. This project blossomed into collaborations between veterans in my immediate community. We would begin by discussing a particular topic, artwork, or object and build a photo around it.

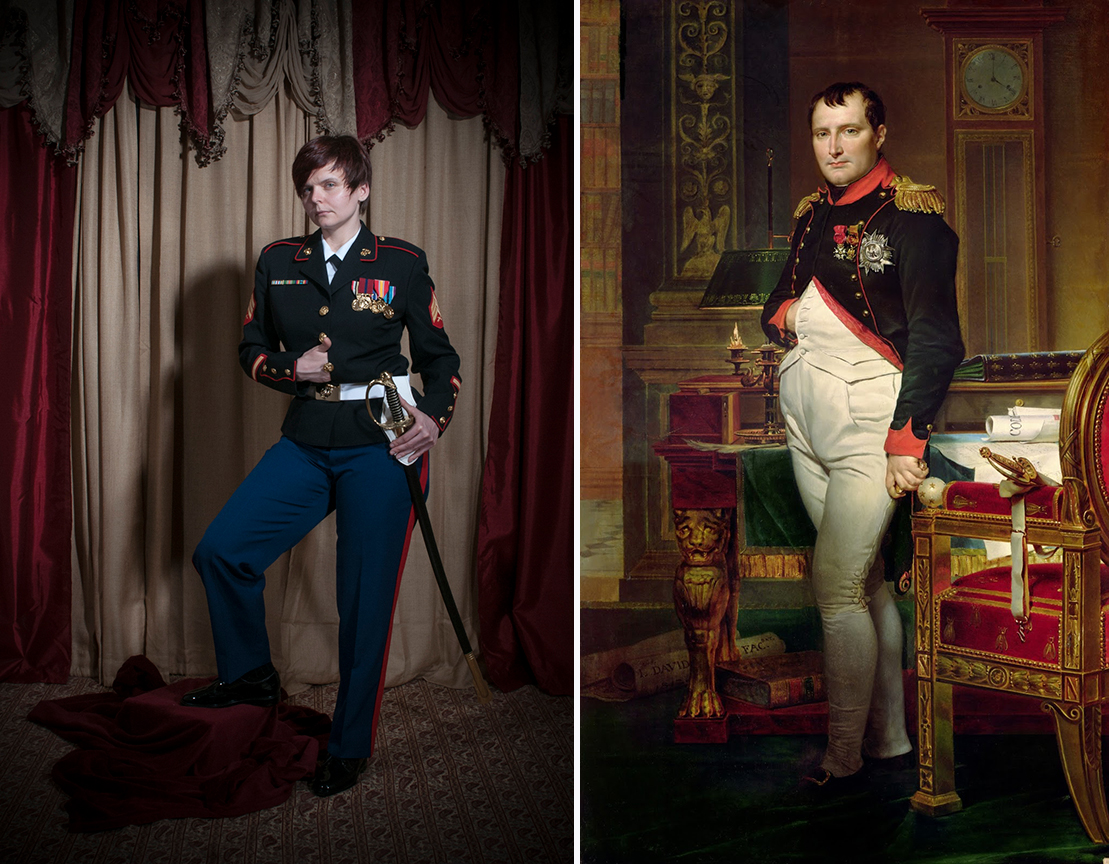

Once such example is The Empress Napoleon:

Left: from Hegemony or Survival

The method of juxtaposing motifs and narratives from Art History with contemporary military culture serves as a vehicle from which to look at the cyclical nature of history.

I recreated Jacques-Louis David’s The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries (1812) with a woman Marine who is an Iraq Veteran and Art Therapist.

The modern battlefield has created space for women to lead men in combat, not being measured by gender but rather ability. Although one could presume the Marine in this photo takes great pride in her ability and position of leadership, we must consider at what cost to her.

After Napoleon’s unprecedented rise to political power (becoming the first emperor of France not born of nobility via his military successes) came subsequent criticisms from both subordinates and opponents. The Marine in the image and the metaphor of a Napoleon complex work in tandem to contrast the experience of feeling that you have to work twice as hard to be taken half as seriously because of your body. In this case, rather than short stature, the correlation is to gender.

From Wargaming

JTD: I’m interested in your series Wargaming, for which you photographed a massive war-game involving 24 NATO countries, 31,000 troops, and thousands of military vehicles. What do you feel are the motivations for individuals to recreate war in this manner? Are the participants primarily veterans? What was your experience, as someone with military experience, photographing this event?

HR: Large-scale exercises are very commonplace in the military. It’s a great barometer for leaders to measure combat “readiness.” Every year there are big exercises with multi-national logistical demands. In some cases, troops are alerted and must be able to report to a location across the Atlantic Ocean within 24hrs. To accomplish this requires pilots, loadmasters, flight plans, loading plans, safety-briefings, and paratroopers jumping out of planes.

To be fair, the first time you parachute a truck out of the back of a plane, shouldn’t be when your life depends on it.

From Wargaming

I’m interested in the theatricality of Wargames, the performativity of masculinity, and the spectacle of power. I’m also interested in how these images function as photographs. They are documentary in form; they are the recordings of an event in time, light, and space. They did in fact take place, however their relationship to truth is dubious.

There is a long history of war imagery used to shape narratives of strength and power, no matter their factual accuracy. Think: Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s 1851 painting, Washington Crossing the Delaware. Washington did in fact cross the Delaware, but did he look this heroic doing it? Probably not, considering Leutze was in Germany when he painted it.

Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware

JTD: Your work focuses on the military, ideas of patriotism, and the experience of veterans in the United States. Because of your personal experience in the Army, there is a kind of tenderness to your work that, at least to me, seems to be lacking in many other projects about the military. To what extent do you think your work depends upon you having shared experiences with your subjects, which allows you to engage on a deeper level than a photographer from the “outside” might be able to do?

HR: It is very important for me to engage with this community however; I don’t believe a photographer must necessarily be a veteran to engage with the topic. It certainly helps but, if veterans only engage with each other about their experiences, then we risk missing valuable insight into our blind spots. Making work about my military service puts my beliefs under scrutiny. The process forces me to think about these experiences very deeply.

From Hegemony or Survival

JTD: Topics such as the military and patriotism are highly charged, socially and politically, perhaps more so now than before. Do you view your work as being sympathetic, critical, some combination of both, or something else entirely?

HR: This is a difficult question for me to buttonhole. I am ambivalent about having a definitive position because I have mixed feelings. My military service does not imply I have underwritten every US Foreign Policy, but I am (as author and veteran Phil Klay describes) proud to have “put myself in a position of responsibility during a time of war.” The more interesting question to me is not one of sincerity or cynicism but rather, if patriotism has in fact become embedded in the lexicon, do we have the consciousness of mind to understand its implications? Are we enablers? Is it political? Is it capitalism? Or is it simply a matter of National Security? Perhaps all of the above when “Support our Troops,” becomes a talking point.

From Wargaming

JTD: Writing about your series An Index of Patriotic Consumption, you state, “I am interested in the commodification, consumption, and representation of patriotism in advertising, media, culture, and religion.” I’m interested in the idea of how patriotism seeps into other aspects of American life and culture, including consumerism. What led you to begin this series, exploring, as you write, a “less discernible national identity”? How did you identify objects to photograph?

HR: I began collecting World War II adverts a couple years ago after discovering that major corporations like Coca-Cola, Nestle, Budweiser, General Motors, and Goodyear were advertising products by likening them to a collective sense of patriotic duty. The ads typically explained that if it was good enough for our “boys on the front line,” then it’s good enough for American Domesticity.

Those ads worked as a springboard for me when I learned of a 2015 Armed Services Committee report by John McCain that disclosed how the Department of Defense spent over 7 million dollars between 2012-2015 to sponsor military-related promotions with NFL teams. That’s when I began creating an index of patriotic consumer culture, often found on the sides of beer cans, ketchup bottles, and Johnson & Johnson Band-Aids. You can spot Digital camouflage and American flags on everything from beans to bullets these days.

From An Index of Patriotic Consumption

JTD: Your work seems especially prescient at this moment, given the current social and political climate in the United States. How has the current political climate affected your work? Do you feel a responsibility to make work that is politically relevant or socially-engaged?

HR: Although the rhetoric has grown vigorously and more people are participating in these conversations, this hasn’t affected my work per se. What I can say is that the political ideologies change over time, but it’s important that our military stays out of the politics, that shape the policies, it’s sworn to uphold. It’s a conflict of interest. This of course becomes increasingly difficult to maintain when major military policy announcements are made via twitter.

JTD: What are you currently working on, and what is on the horizon for you as an artist?

HR: A classmate recommended a text by Hito Steyerl titled A Tank on a Pedestal: Museums in an Age of Planetary Civil War. It’s been very helpful and piqued my interest in military and political monuments, especially ones that have been defaced as symbolic acts of protest. These include the widely broadcast toppling of a Saddam Hussein statue in Baghdad, the over 3,500 Lenin statues removed throughout Ukraine since the fall of the Soviet Union, and a destroyed Hugo Chavez monument in Venezuela. I’m unsure if the research will make for interesting pictures, but I’m excited by the potential.

JTD: Thank you so much, Hector. It has been wonderful talking with you!

From An Index of Patriotic Consumption