Q&A: Frankie Rice

By Rafael Soldi | March 12, 2020

Frankie Rice was born in Truro, Massachusetts and lives and works in Brooklyn, NY and on the Outer Cape in Massachusetts. Previous exhibitions include “The name of this show is not: GAY ART NOW” curated by Jack Pierson, Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY (2006); “Eliminate” curated by John Waters, Albert Merola Gallery, Provincetown, MA (2007); “Wrestle,” Launch F18, New York, NY (2011); "(con)Text, curated by Tim Donovan, Sharon Arts Center, Peterborough, NH (2013), and "The Violators," Leslie-Lohman Museum, New York, NY (2018). Rice’s most recent solo exhibition, “The Arches” opened at LAUNCH F18, New York in October, 2019.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Frankie, thanks for chatting with us.

Frankie Rice: Hi Rafael. It’s my pleasure. Thank you for your interest.

RS: Let’s start at the beginning. Where are you from? How has this influenced the shape your work has taken over the years?

FR: I’m from Truro, Massachusetts, the town next to Provincetown on Cape Cod. The most influential thing about growing up on the Cape was all the nature.

Provincetown is an artist community and in the begging artists would go there for the clay and the light. My earliest work was very primal. I sculpted with stone, wood, horse hair, bones just mother nature and in her elements. After that it’s just a lucky place to begin for artist. Theres a lot of amazing talent and influence that flows through there, and it has an amazing past.

Hans Hofmann, Robert Motherwell, Norman Mailer lived at a time and made work in Provincetown. Even Warhol and the Velvet Underground preformed there one September. The culture is still alive thanks partly to the film festival, the Fine Arts Work Center.

RS: You’ve spoken of your work as a sort of “flip book,” where you iterate subtly on past works and your practice evolves slowly but always as part one single overarching narrative. Can you expand on this way of working, as opposed to single projects or themes?

FR: I believe in art telling a story. Even if my last piece is drastically different from my first, I want it to be known how I got there. I challenge myself to take each new piece a subtle step further. I'm not looking to shock my viewers—just a pleasant surprise. Movement plays an important role in all my work; in the individual pieces themselves and in the fluidity from one idea to the next.

RS: Why arches?

FR: I love idea that anyone can take a shape and over time create a language. Hopefully one that can speak for itself. I'm attracted to the history of the archway. First Etruscans and then ancient Rome. It’s such a simple shape that can comfortably reference monumental power, both astonishing and frightening. I see it mostly as a symbol strength and pressure.

I built my first arches from driftwood. It wasn't just driftwood, I looked for the whole root structure of trees. The ocean has a way of stripping and polishing wood so relentlessly that it can appear almost petrified—that’s the wood I wanted. What first attracted me to the archway was all its romance. When anyone ever walks through one they most likely enter someplace beautiful: Gardens, cathedrals. It’s been a long journey from where I was then to where I am now with my sculptures.

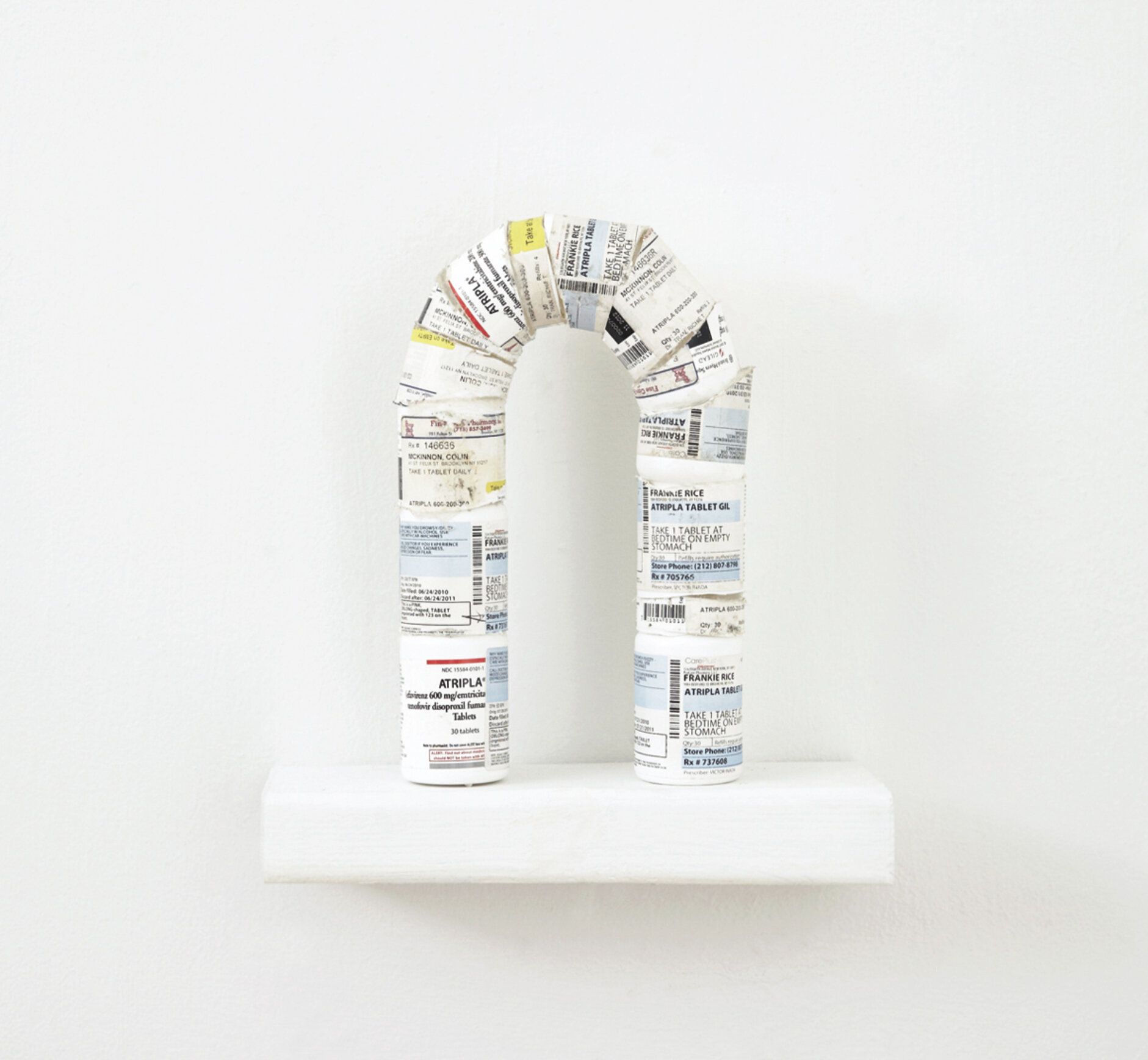

Truvada, 2012, Mixed media (Courtesy the artist and LAUNCH F18)

Rafael Soldi: For many years now you’ve made sculptures with bottles of HIV medication. How has this work evolved for you as drugs such as PrEP have changed the landscape and begun to erase the stigma of HIV in the queer community? [PrEP is a daily pill that HIV-negative people can take to reduce their risk of becoming infected if they are exposed to the virus by 99%]

FR: I was diagnosed with HIV before I could drink in a bar legally. I found out I was positive by having sex with some one that told me he was positive after the fact. I raced to the hospital because I heard about a drug you could take in the first 24 hours of being infected that gave you a 70% chance you wouldn't be. The doctors gave me 3 medications but the main drug was Crixivan. It felt like I had just been poisoned. I couldn't get the taste of it out of my cotton mouth and it was less then a week before I started pissing blood and had to stop taking it. I was already positive, not for the boy that scared me in to getting tested but from another time before. It remains a mystery.

After that, my closest friend, Caroline Thomson, made a call to David Armstrong who set me up with some fancy clinic in Manhattan. The doctor there prescribed the latest method of treatment: going on and off on and off medication. A method that proved later to make people totally resistant to the drugs. I feel very fortunate I didn't take that advice. Maybe because of what I went through with the Crixivan, those pills scared the hell out of me. So much, in fact, that my virus load was in the high millions before I started treatment. Eventually I began to take Atripla, one pill a day. That’s when I started to sculpt with the bottles. Every bottle in the archway was making me stronger. I looked forward to every bottle because I wanted to see the end to my sculpture. By that time my virus lode was zero. I look back on that work and remember how afraid I was and all the people that were there for me.

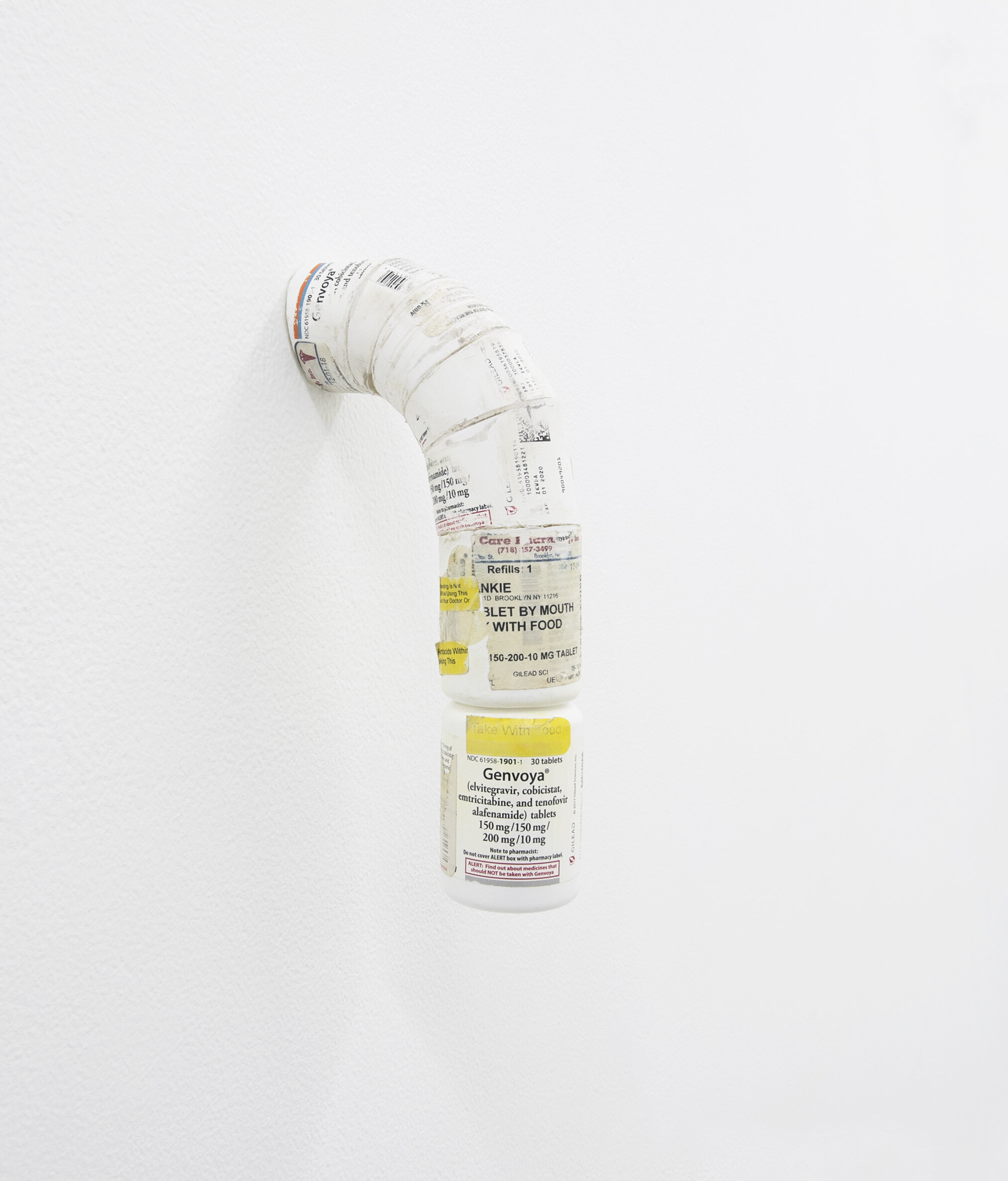

I didn't realize how tired I had been the five years I was on Atripla until I switched over and started sculpting with Genvoya bottles. Now I'm sculpting for the first time with Biktarvy bottles.

I’m part of generation that can’t imagine the terror and loss of the AIDS epidemic, but part of a generation that remembers what it was like to be in love and be afraid to make love.

. What it’s like to have an HIV-negative lover and feel his fear of you.

RS: How do you source the materials for the Truvada sculptures?

FR: The first sculpture I made out of Truvada bottles came directly from the first HIV-negative person to tell me he wasn't afraid at all and then showed me how he meant it.

RS: What role does humor or lightheartedness—if at all—play in your work when addressing difficult subject matter?

FR: The half archways that hang off the wall can suggest a row of limp dicks coming out of a glory holes. I have never participated in the event of a glory hole because I can't think of anything less romantic.

Still, I wanted the work to feel elegant and pitiful . Glory holes are a funny because you never know who's behind them. With this work you can imagine someone waiting there for action that will never come.

RS: In contrast to the pill bottle sculptures—which rely on synthetic materials, are smaller in scale, and can't escape their relationship to pharmaceutical innovation—your new works in stone are monolithic, elegant, and more abstract, in deeper conversation with the history of sculpture. Can you share more about your return to nature, your process, and the lean toward abstraction?

FR: Granite is a challenging material to work with. It can break where it wants and it’s incredibly dense. You have to commit to a great deal of labor and it takes a lot of patience.

What I favor about granite is its age, roughly 2 billon years old. It’s a material that demands a certain respect, automatically and entirely on its own.

I aim to make a balance between the genuine texture or shape of the stone and the polished reflection of my carving. I feel at home with the material. This work is the closest to my earliest work only because it is so natural and I get to be outdoors when I carve. My process is as simple as drawing a line in the stone and taking away everything on the other side of that line. I use a diamond blade to take away the big stuff, and chisels and grinders to get my shape. I then polish it with water and polishing pads.

I’m moving a little away from the conventional shape of the arch but not so abstract that the shape can't be found with in my new work. It’s an exciting time for me because my arches—and where I can take them—feel limitless.

RS: What’s next for you?

FR: I can't predict the future and I won't really know what my next work will look like until I’ve finished what I'm working on now. My plan for the future is to keep making work the way I always have.