Q&A: esther macy nooner

By Zora J Murff | April 19th, 2018

Esther Nooner was raised dividing time between Maryland and Arkansas. She spent much of her childhood exploring coastal and rural terrains that provided a fundamental belief in the necessity and importance of Nature to human beings. Historic photographers and travel influence her research and studio practice.

Nooner received her B.F.A in Photography from Andrews University in Berrien Springs, MI and is currently pursuing M.F.A. in Photography from University of Arkansas School of Art.

Zora J Murff (ZJM): Hi Esther! I’m so glad that I have the chance to catch up with you here. When we met for a studio visit, it was right before your thesis exhibition. How’d it turn out? More importantly, have you had some time to relax?

Esther Macy Nooner (EMN): Hi Zora! It is lovely to catch up with you as well!

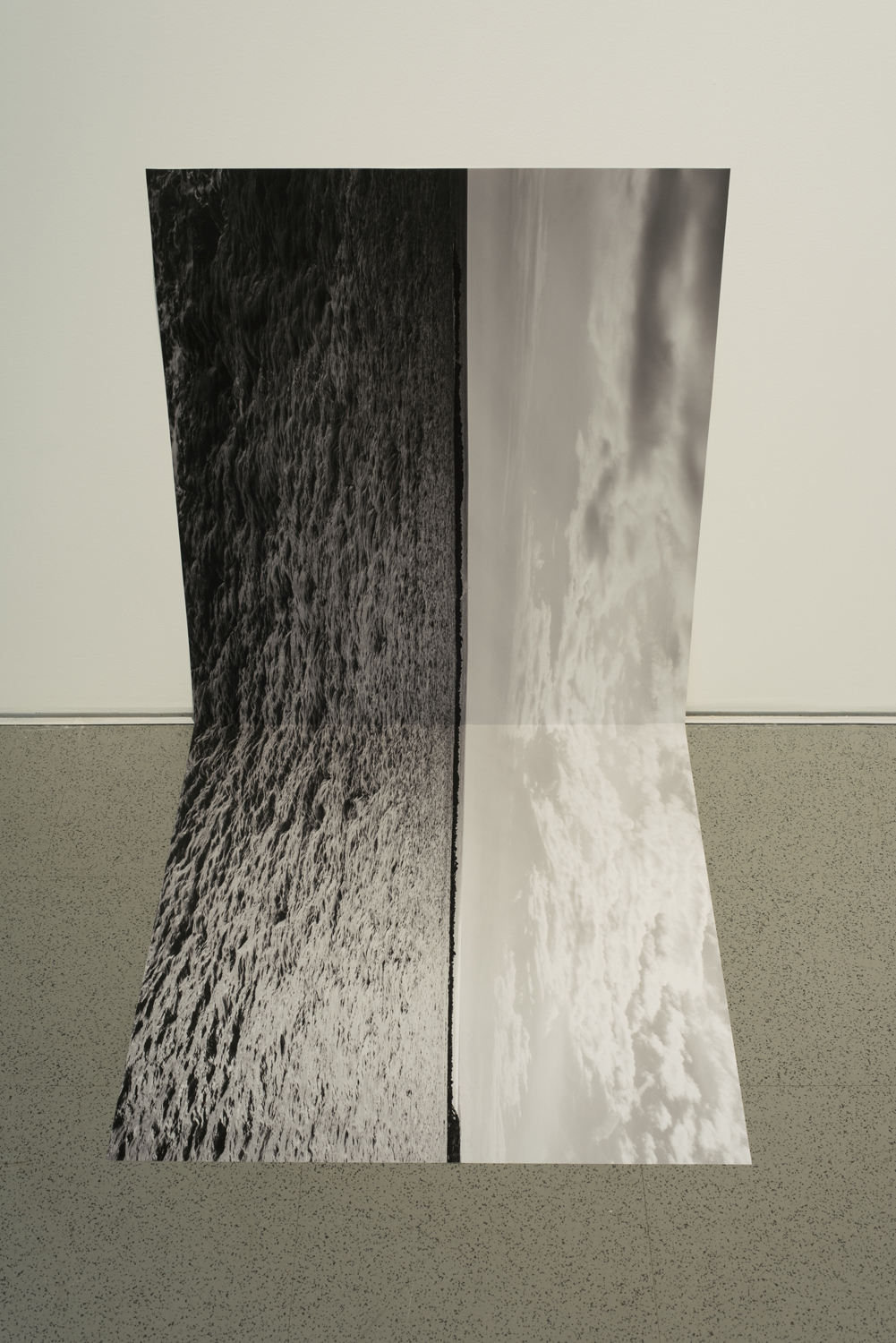

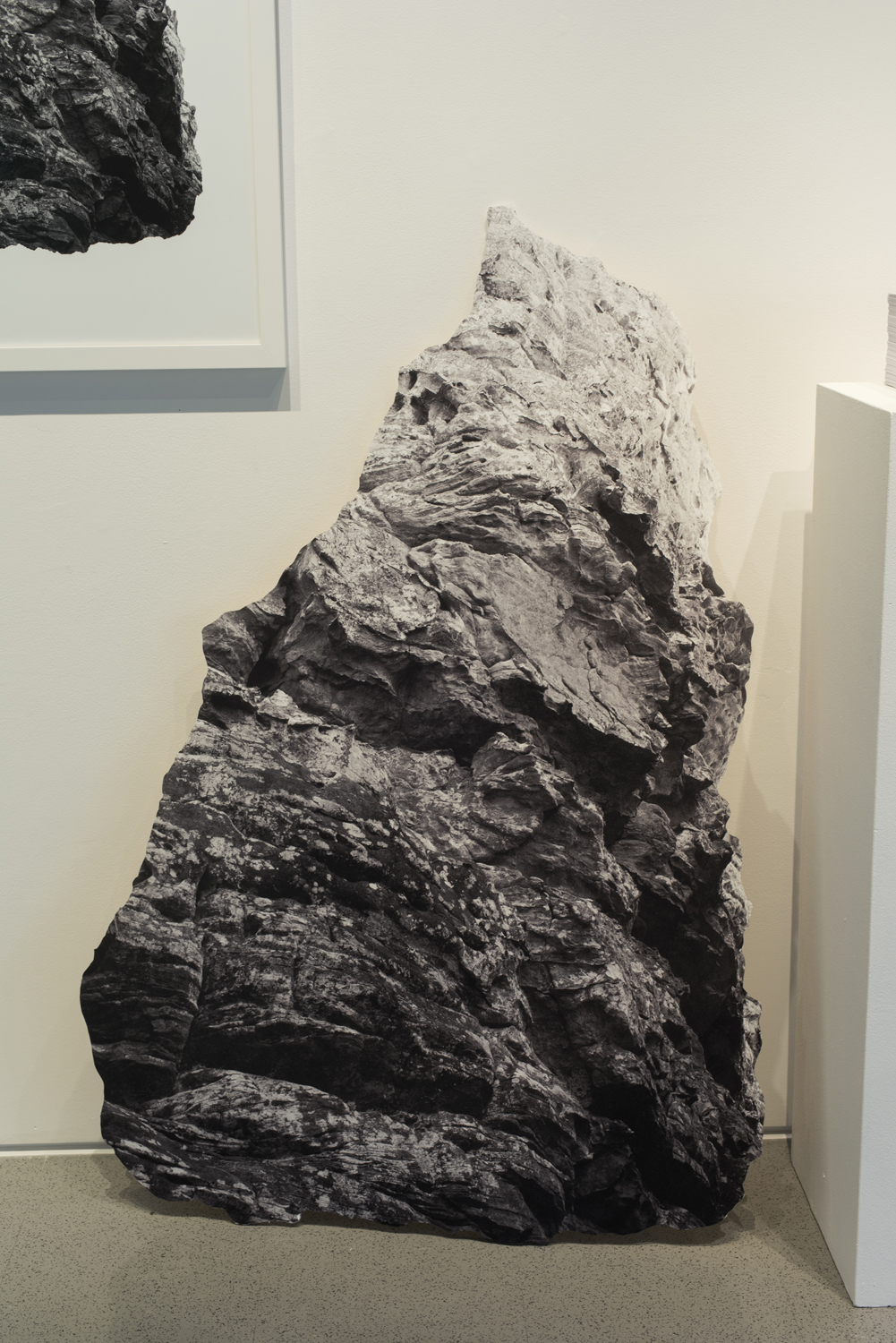

Yes, when we last spoke I was a little over a week away from installing my Thesis Exhibition Modified Landscapes. The show was great and it was certainly very satisfying seeing each piece in a finished space and able to play off each other since my objects vary in form and placement.

As far as relaxing goes, I thought that after the show was up, documented and then de-installed I would feel some sort of relief but it’s actually the opposite. Now I am in finishing writing my thesis paper along with applying to residences and teaching positions, thinking about summer plans and more importantly how I want to continue my research and pushing forward studio wise.

ZJM: Let’s start by getting to know you a bit better.

EMN: I was born on the east coast in Maryland and lived there till I was about 14. As a kid, I wanted to be outside as much as I could. When I got home from school I would come in the front door, drop my backpack and head out the back door to the woods behind our house. My friends and I would wander and explore as far and wide as we could. I seemed to always be the one coming home muddy and wet from falling in some creek. Additionally, I would spend my summers at my grandparents farm in Arkansas where I was given all the freedom to run around, explore and kinda get lost but in a safe place where I could always orient myself (like not getting lost geographically but freedom and space to allow my head to wander).

My grandparents farm has always taken the place of what I consider home. Like so many people of my generation, I grew up in a split, but still very loving, home. This place in Arkansas, which my grandmother called the “Promised Land”, is still to this day constant safe haven.

My love and appreciation for those wandering and exploring moments certainly impacted my thought on Nature and its importance.

ZJM: What led you to your current work?

EMN: So my first year of graduate school I felt a little bit like a fish out of water. The experimental phase of making work was certainly needed for my research but I felt like I had no idea what I wanted to say or explore.

Then I had an experience.

I was fortunate enough to go to Iceland for a few weeks the summer between my first and second year of graduate school. It was terrain like I had never seen before. So open, vast and seemingly wild and untouched. I was amazed and so curious. Then I came back and was abruptly shaken by the contrast in how we regard the care of Nature.

I also returned with gigabytes of images and I would go through them and think “Now what am I supposed to do with these?” The image on the screen or even in the print was nothing like what I had experienced and I was discontented. My connection to the actual space was getting in the way of the photograph.

I don’t exactly remember how or why but I started cutting the prints I had in my studio. (Looking back, I was thinking in a similar vein my first year when I was tracing over photographs...it all comes full circle eventually.) I was simply dissecting landscapes in a formal sense by breaking up foreground, middle ground and sky. Then I was trying to bring them off the wall a bit and all of a sudden the photograph became an object. The highly respected “Frame” had been disjointed and it became the object rather than a window.

ZJM: In your statement you reference Romanticized landscape, photographic representation, and truth. Can you break this out a little bit?

EMN: After some time of experimentation with the photograph, the landscape represented became a meditative space. My incisions and marks within the photograph became a representation of my hand in Nature.

Historically speaking, landscape representations in painting or photography, have a deep Romantic ideologies attached. This notion of Nature being untouchable is far from appropriate considering the current state of our climate. Our use of unavoidable materials speak to convenience and ease rather than the wellbeing and consideration of the earth.

Photography is a means of communication and an extremely influential way we absorb information. The more I see landscape photographs of “wild” or “untouched” wilderness the more I realize those images do not reveal the accurate state of Nature. My scarring the photograph itself illustrates how this view of what seems to be un-hindered, its actually false.

ZJM: I often touch on this idea a little bit with my beginning students when we look at early survey photographs, or Ansel Adams. I’d be interested in hearing your thoughts on our desire for the landscape or Nature that appears untouched, and do you think your work serves as a sort of dissonance experience?

EMN: Our desire for Nature is simple, yet complicated. It is a place and subject that has been returned to by writers, visual artists and those who hunger for some connection that doesn’t come with internet. After the industrial revolution Nature was returned by painters as a response to urban and city life. Thinking of a 21st century example, Cheryl Strayed’s Wild was a return to wilderness as a way of healing. Nature has been a means of spiritual guidance and connection. Connection to what, you ask? I say that is up to everyone’s personal, individual belief system.

Nature reminds me of my capabilities, physical and mental. It also reminds me of how little I actually need to live. I went backpacking this past summer and was awakened by how much stuff we possess that we actually don’t need.

I guess what I am saying is that provides an incomparable experience.

I also think that we do want “what appears untouched” rather than nature that is actually not groomed or manicured. National Parks are a great example of how we want to experience curated views from the air conditioned tour bus. I am guilty of it, myself.

My work provides a distant and tense view of a represented space. The manipulations to the photographic object are meant to bring the viewer out of the “window” mentality and to activate thought about the content. During my thesis exhibition reception, a student came up to me and asked if a particular piece was meant to be frustrating. My answer is yes. I am purposefully denying the viewer the romantic engagement often times associated with landscape photographs because that entrance doesn’t leave much room for critical thought.

ZJM: How do you think your work connects to contemporary political issues regarding the landscape and Nature?

EMN: Political and environmental issues are certainly swirling around in my thought and research. Especially when National Parks are under threat and things like drilling for oil become a priority over people. Chemical dump regulations, mountaintop coal mining, glaciers melting, car emissions... the list goes on and on regarding ways we can talk about or even visually represent how we account for our waste and trace of materials. My interests and concerns are more with why we make these choices and how, if possible, we can modify our belief system that has caused the damage already done. Societies need for power and domination, issues associated with our patriarchal system, are what control the laws and regulations that harm the earth. If anyone out there reading this is interested, one of my main sources of research is a book by Timothy Morton titled Ecology Without Nature. I highly recommend it and have read and reread many chapters. The more I read, the more I understand how we have gotten to this point but, unfortunately, I become less hopeful of a true, fundamental shift especially given this current administration's lack of platform on environmental issues. I am depressing myself as I respond to the question so let me bring the optimism back! I know that laws and legislation have not always had the health of Nature in mind but we as individuals have that choice. Decisions we make everyday have the ability to put less in landfills and to even simply consider the materials we use. This small consideration can shift what we use and/or how much. This is really what I want my work to facilitate, a moment of meditation and questioning the disruption within the image to maybe evoke some thought on removal and manipulation of Nature.

ZJM: When I was in your studio, I was intrigued by your multimedia approach, especially the lightbox piece. Can you talk about how the lightbox piece specifically fits into the work?

EMN: As soon as I began dissecting and cutting photographs, they immediately became sculptural. The “window” was shattered and they became objects.

I felt that this methodology, of breaking the frame, was a meditative means to question the content. What does it mean when an element of Nature is sliced open? Dissected? The piece you are speaking of directly incorporates some fundamental elements of photography which is very important to how I think and work in a very general sense. The artificial light that beams through the cut paper is acting as this vehicle for artifice. Exploring the photograph as ink on paper and as a space or thing represented. The light box itself certainly carried a history, being part of the traditional photographic process and my choice to expose the power cord is certainly important because I wanted viewers to know that it’s powered, again, artificially. The image itself was chosen for the sand/grain play, again touching on representation and the medium.

ZJM: I was with a group of students earlier today in my thesis exhibition, and one of them asked me what the one big takeaway was for me personally. Now I’m interested in what yours was?

EMN: I think my biggest takeaway is my continuing drive. Not feeling like this work is done or complete is a blessing because I know it will fuel me as I get out of the safety net of graduate school.

ZJM: What’s next for you?

EMN: I have to say that, even though I feel really good about how my show came together, I am left feeling slightly unsatisfied. I am eager to keep going. I have many more methods and materials I want to experiment with and perhaps add and expand my installations. I have also kept some waste-like scraps and ruined prints that have taken on a sculptural mountain in my studio which has become a great interest and I want to explore it further. One thing I love about my process is that is allows for endless experimentation and trial and error. The downfall to this is deciding when something is done or how to finish it but it’s a great freedom to have the ability to wander within the medium and materials.