Q&A: Elinor Carucci

By Rafael Soldi | Published on May 11, 2017

Born 1971 in Jerusalem, Israel, Elinor Carucci graduated in 1995 from Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design with a degree in photography, and moved to New York that same year. In a relatively short amount of time, her work has been included in an impressive amount of solo and group exhibitions worldwide, solo shows include Edwynn Houk gallery, Fifty One Fine Art Gallery, James Hyman and Gagosian Gallery, London among others and group show include The Museum of Modern Art New York and The Photographers' Gallery, London.

Her photographs are included in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art New York, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Houston Museum of Fine Art, among others and her work appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, Details, New York Magazine, W, Aperture, ARTnews and many more publications.

She was awarded the International Center of Photography's Infinity Award for Young Photographer in 2001, The Guggenheim Fellowship in 2002 and NYFA in 2010. Carucci has published three monographs to date, Closer, Chronicle Books 2002, Diary of a dancer, SteidlMack 2005, and MOTHER, Prestel 2014. Carucci currently teaches at the graduate program of photography at School of Visual Arts and represented by Edwynn Houk Gallery.

Rafael Soldi: Let’s start at the beginning. You were born in Israel and relocated the U.S. in the 90s to pursue photography, is that right?

Elinor Carucci: I actually had my education in Jerusalem at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. After high school I did my armed service, and after university I decided to come to New York mainly for my work, for my photography career. Many of my teachers did their education here and I have an aunt here and I had visited New York as a teenager—New York was the heart of photography. I’ve been here since 1995, in the same neighborhood, in Chelsea.

RS: You started early on with photographs of your mother. How did this project start and how did it affect that relationship?

EC: I was young, 15 or 16, when I picked up my father’s camera. I looked for something to do and wandered into my mother’s room. She had just woken up from an afternoon nap and I took maybe one or two pictures of her. I continued to take pictures of her, of me, and my parents—I just feel like there was so much more I could see and feel with a camera than without. Since then I’ve wanted to stay with the camera, I experience and feel more with the camera.

RS: These are not always easy images but they really set the stage for what has becomea decades long career photographing intimate life and the struggles of everyday life. In Crisis and in Pain, for example, we continue to see your family, yourself, your relationship as lead characters on what seems like a difficult time in your life. Was it natural for you to document theses times, or was it a struggle?

EC: It’s really the way I was raised, photography is a result of who I am and not the other way around. I am a person who believes in sharing and showing photos of loss, and pain, and insecurities. I think that’s the only way for me to survive, it makes these difficult moments more bearable.

My mother and I, 2001

RS: Right, so if you have not had photography in your life, do you think these things would have been more difficult to deal with?

EC: I guess I would, this can tricky because the fact that photography can be therapeutic for us doesn’t mean we create good photography. I’m careful not to mix the two, what is helpful for me mentally is not always necessarily what is an interesting image, complex, universal. Sometimes a therapeutic process is developing into a performance of some sort, that I then document in order to tell a story that has to do with the pain or the challenge. But I guess that I would find a way to deal with difficulties even without the photography... I would hope! Maybe a way that has to do with connecting to people in the same way that I feel I do with my photography but through another venue.

RS: Conversely, we also see Comfort, a body of work that clearly culls images from those same difficult times but these are soft, they are beautiful, tender moments of respite, of nurturing—always featuring your mother, and sometimes your father, you return to your roots.

EC: Right, also with MOTHER. I am really going against the notion that being sentimental or emotional is not accepted in the fine art world. There are even, I dare to say, sweet moments with my mom in Comfort as you said and in MOTHER, happy moments that are sentimental. They are part of every day life, but especially at the time I was having such a hard time with my marriage and my health that I needed even more of my parents love.

RS: And this is interesting because shortly after that, you become a mother yourself—all of a sudden the roles reverse but you still have the camera in your hand.

EC: Becoming a mother really affected me. From the beginning I felt so many outbursts of emotion, the way I felt could change from one moment to the next—it was a very overwhelming emotional experience. I think I was a little bit angry that all the art and photography I had studied presented idealized images of motherhood, like the madonna and child—everything was so perfect. So there was even more of a need to try portray a complex and honest story of becoming a mother.

Dry Snut, 2005

RS: How much of your process is setting up a shot like a tableau and how much is totally candid?

EC: It’s a range from being completely candid, especially the ones that I’m not in, to ones where I set up lights and clean up the background at home. But I feel like even with the ones where I set up lights where the technical aspects are very controlled, the emotional state and the moments that happen a few minutes before the shoot are something that I didn’t necessarily think about, and these manifest in the image. There is a lot of preparation some times—lights, tripods, stands; specially if I’m in the image, it can’t be spontaneous. I think I can never be completely spontaneous, I let myself live my life in front of the camera. The moments that are truly spontaneous are the ones when I’m not in the image, or when there aren’t any lights, they are complete snapshots. And even within a controlled image, a snapshot can still happen, you never know especially with children.

RS: And you switched from film to digital, is that right?

EC: Yes, in 2008 I switch to digital.

RS: How did this affect your process?

EC: It has really had a positive effect. Even with things like self timer, I can set up the digital camera to shoot multiple frames at a time. Or if my husband or one of my children are helping, I can just have them continually press the shutter without fear of wasting film, I can see what’s working and what’s not. And especially shooting my family, and even on assignment, the fact that I can show the pictures to them or the strangers I’m shooting is something that I welcome. It helps build collaboration and trust and respect.

RS: Speaking of assignments, you’re also an active editorial photographer, and I find that often the assignments you shoot are in line your personal work. How has that relationship developed with editors and have these assignments informed your work?

EC: Definitely, this took some years to develop. In 1998 when I started to shoot editorial work, I was assigned things that weren’t a great fit. Overtime editors became more familiar with my work and started assigning stories that were a better fit with my interests and abilities. One feeds the other—the more I had exhibitions and books, the more photo editors paid attention. For me maybe Joanna Milter, when she was at the New York Times Magazine as Kathy Ryan's deputy, she really recognized the type of photographer I am, and what I do well. She started giving one story after another, a lot of them cover stories, and I started following her, she is now the Director of Photography at The New Yorker. She was significant to this process.

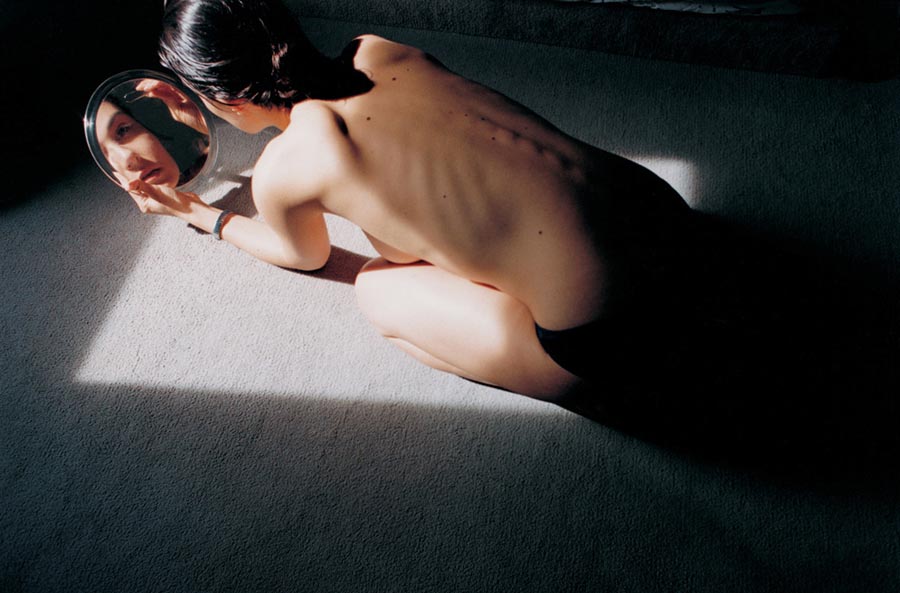

Mirror reflection, 1999

RS: A few people I know have mentioned you as an inspiring and impactful teacher in their lives. You teach at the MFA program at the School of Visual Arts. How did you land there?

EC: That’s good to know! That means a lot to me, I try to give all that I can to my students. I started teaching in the BFA program about 17 years ago. It was Stephen Fraiely actually who brought me on. I was a little afraid of teaching, about my English. I told him I wasn’t sure if I could teach, and he asked me, can you be generous? And I thought about it for a minute and said, yes, I can be generous. And he said, if you can be generous, you can be a teacher. And that has really stuck with me. And you know, as a teacher sometimes you hit a wall—you don’t always connect or they don’t always connect to you. But this was really inspiring. Eventually I moved on to the MFA program, and I love this journey that we go on, we travel together for a period of time when I hope to help them get to the core to who they want to be as artist and hopefully I can help in those steps.

RS: We’re in a political climate currently that truly affects us all, but especially artists, women, and families. Do you see these next four years having an impact on your work?

EC: The most impact for me, even though he didn’t end up being president, was Bernie Sanders. Something really lit up for me when I heard him speak the first time, and then I became a volunteer. Even though I am worried, for me I think a lot about how Bernie represents so much of how I feel and in a way what I’ve reflected in my work. Whenever he was asked about whether or not he was religious he spoke about humanity and less about religion even though he’s Jewish. That really has an impact on me, as an artist, as a mother, and as an American. So I hope that his values and what he stands for will stay relevant in the age of Trump and will permeate into the lives of and minds of who America really is. I’m trying to stay optimistic, I’m very worried, but I’m trying to stay optimistic!

All images © Elinor Carucci