Q&A: debe arlook

By Jess T. Dugan | June 16, 2022

Debe Arlook is a visual artist based in Santa Monica, California. She received a B.A. in film and media and a minor in psychology from American University in Washington D.C. Her work is exhibited nationally and internationally including Lishui Art Museum, Museum of Art and History Lancaster, Griffin Museum of Photography, Center for Fine Art Photography and the San Diego Art Institute. Recognition for her work includes the CENTER Social Award Honorable Mention (2022) and Critical Mass Finalist (2020, 2021).

Using diverse photographic styles and processes, Arlook’s portfolio is a combination of straight photography and conceptual work. Her fascination with one’s relationship to self, others and the natural world is the throughline in all her projects. Her studies in filmmaking, spiritual growth and psychology inform her work. Arlook is an instructor at the Los Angeles Center of Photography; advisor with Pasadena Photography Arts; and contributing editor and resource manager for the PhotoBook Journal. She founded Arlook Printing Services in 2016 and is based in Los Angeles, California.

This interview is in collaboration with CENTER and is part of a series featuring the winners of the 2022 Social Award, juried by Jess T. Dugan.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Debe! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. I’m excited to speak with you in depth about your project one, one thousand..., but before we jump in, could you tell me about your background? What was your path to discovering photography, and how did you get to where you are today?

Debe Arlook: Hi Jess, it’s so cool to talk to you! Congratulations on your book, Look at me like you love me, and the two exhibitions in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery!!! You are making important historical work and touching many hearts. I’m thrilled we’re doing this, thank you.

To your question, I grew up in central New Jersey in a liberal middle-class Jewish family. I was a tomboy and the middle child of three sisters. It was during the ‘60s and ‘70s when kids played kickball on the street and stayed out until we heard our mothers call us home for dinner.

We spent summers in the Catskill Mountains in upstate New York where my grandparents owned a bungalow colony. My sisters and cousins and I spent our days creating adventures in the dense woods of the property. On weekends, summer residents gathered in the casino to play bingo and watch classic movies like “Under the Yum Yum Tree” with Jack Lemmon. With fresh popcorn and a box of Goobers, it’s no wonder these events sparked my love for films.

My dad was the family documentarian, shooting stills with a Brownie Bullet and an 8mm film camera. They gave me a Kodak Agfamatic when I was eight years old. I remember taking it everywhere and specifically being drawn to photograph the bark of trees. Not the typical subject matter for a little kid.

Fast forward to American University in Washington, D.C., where I majored in media and filmmaking with a minor in psychology. The summer I graduated, I packed up my car and drove across the country to L.A. to break into the film industry and direct movies. I was on this trajectory when I fell in love and got married. I had three kids by the age of 30 and put my career on hold. Years later, when it was time to get back to work, I did not return to the film industry. I had experienced enough of the not-so-nice side of Hollywood. Instead, I chose to return to photography and the purity of the single frame.

In 2002, I began taking workshops at Julia Dean Photo Workshops. I studied with Julia and Aline Smithson consistently for years. With Julia’s street/photojournalistic background and Aline’s design/conceptual background, I began an explorative dive into different photographic styles. At that time, my marriage was on the decline and I began asking myself the big existential questions. This led to a different kind of deep dive into spiritual studies and eventually becoming certified as a life coach. All of this literally and figuratively informed the lens through which I view life, and is the foundation of my work.

Floor plan

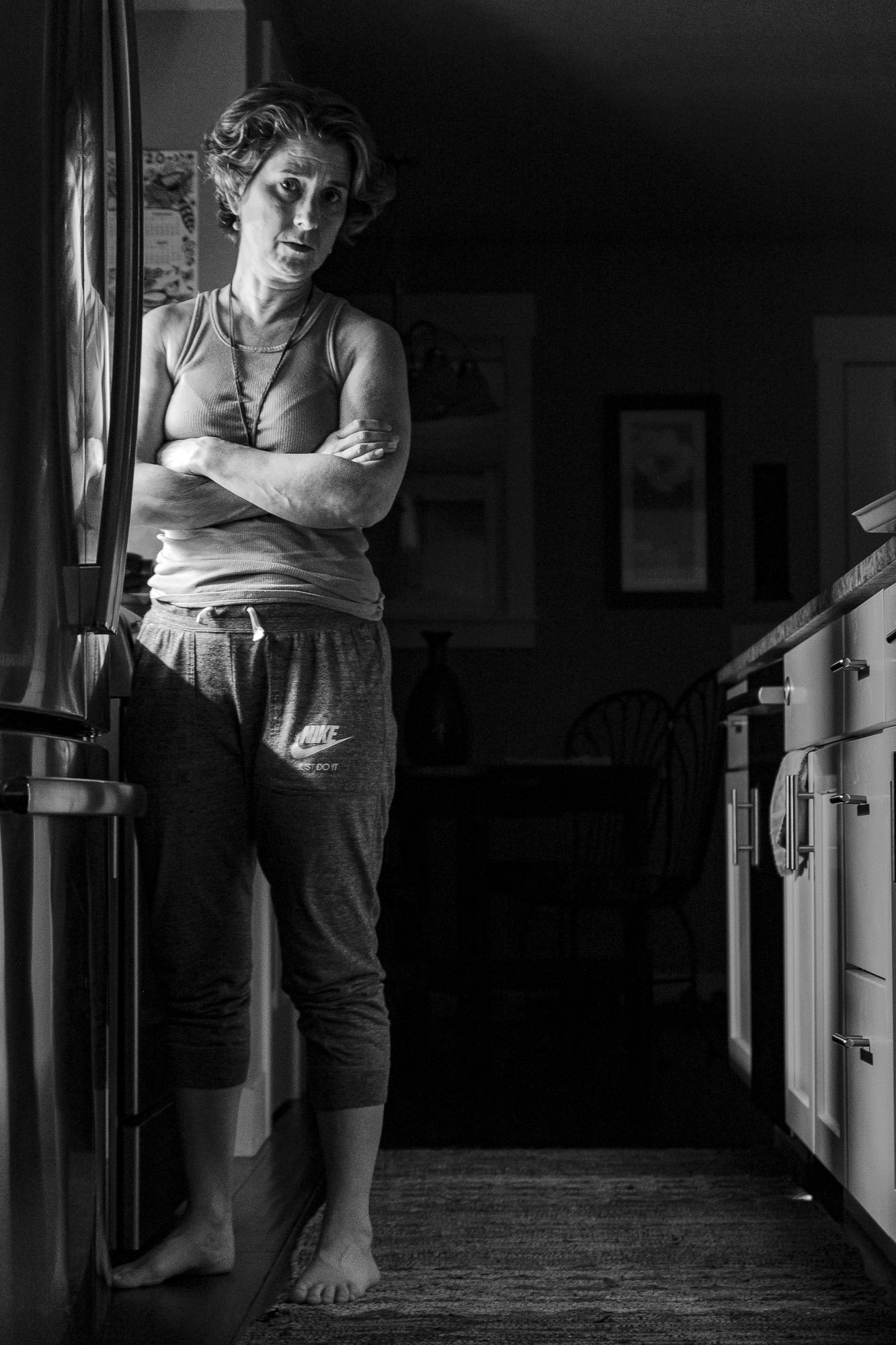

JTD: Tell me about one, one thousand..., which tells the story of your 28-year-old nephew, David, who has Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome, an incurable seizure disorder, and severe autism, rendering him non-verbal and in need of full-time care. How did this project come to be? Can you tell me a bit more about David and his mother, who is also part of the project?

DA: During the first summer of the pandemic, I visited my family in Colorado. I was photographing David when this message popped into my head, “You need to make a project about David and Lori.” I lowered the camera and felt the enormity of what I heard. The timing couldn’t be better. With so many Covid restrictions back in Los Angeles, it was easy to extend my stay. In making this work, I could be a witness to my sister’s life as a single parent and caregiver and be a “voice” for David. I had no idea what the project would look like, I just knew telling their story was important for the three of us. Since David was an infant, I had been emotionally supporting my sister as she struggled with his disorder and raised two other boys. This project was a way for me to support her on a deeper level.

Lori has been working on a book for years. I envisioned using her writings along with the photographs. When I asked if we could do this, she froze and went silent. Waiting for the answer I remember thinking, “you HAVE to say yes, we’re meant to do this!” The three of us were standing there with Lori and me both close to tears. She knew she’d be exposing very private moments of their lives but also knew that by doing so, their story would touch others in unimaginable ways. At a tender moment, she quietly said, “Okay.”

Meds in bed

I love that you asked about David. Most people don’t because they can more easily relate to Lori. David is a sweet soul. He is gentle-natured and has an unexplainable “knowing” about him. He communicates mostly through his eyes, his smile, and a variety of vocal sounds depending on his mood. He makes soothing, repetitive humming sounds when he’s at ease, a lyrical squeal when he’s happy. There’s this great story about David’s vocal toning at a conference on autism that Lori and David attended. A woman came up to Lori during the event to tell her that David’s vocal toning healed her stomach pain. Moments later, the presenter approached Lori to say that David’s toning soothed her nerves during her speech. Lori was shocked. She had been trying to keep David quiet during the speech. She had never heard of vocal toning or its healing effects.

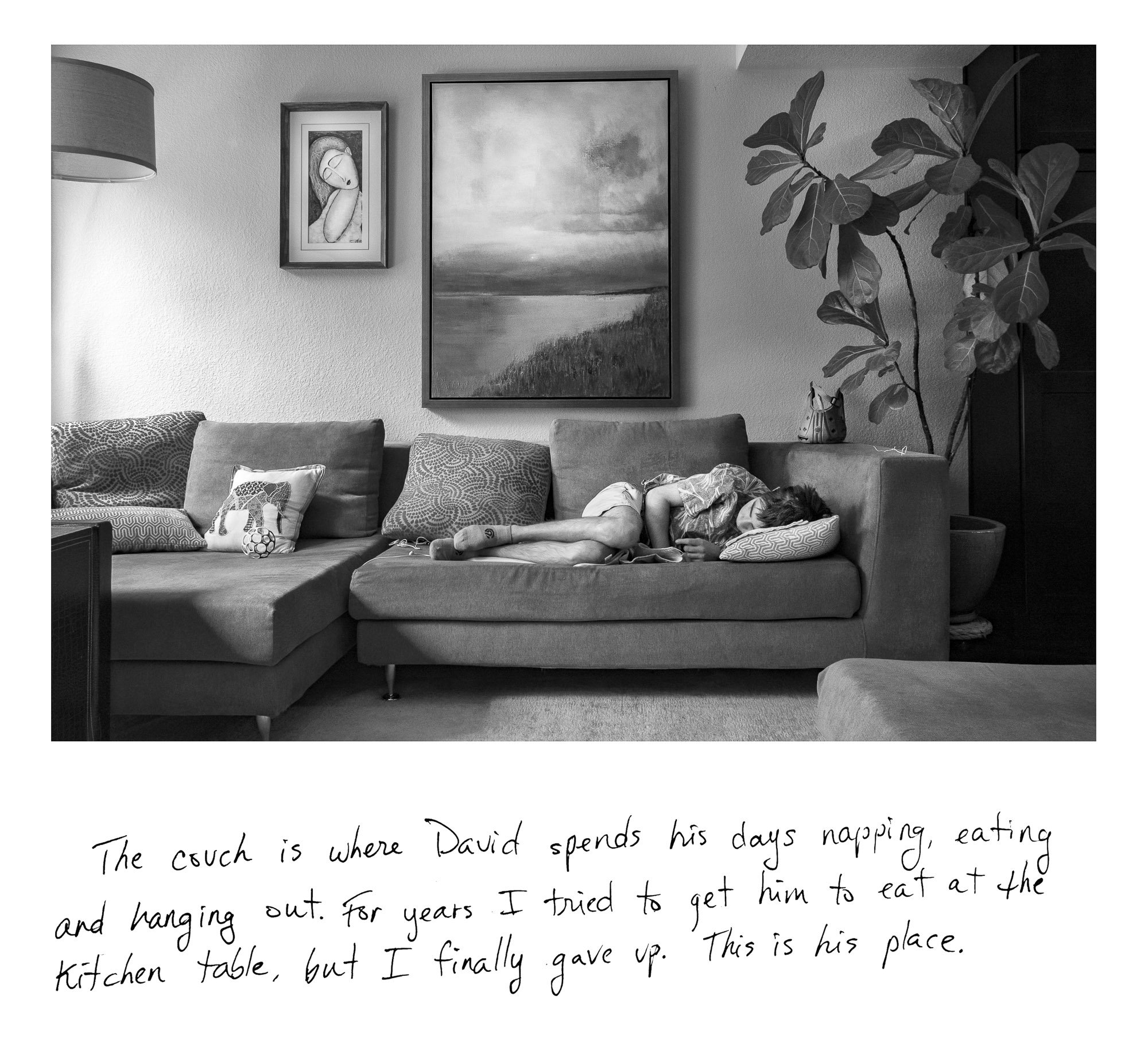

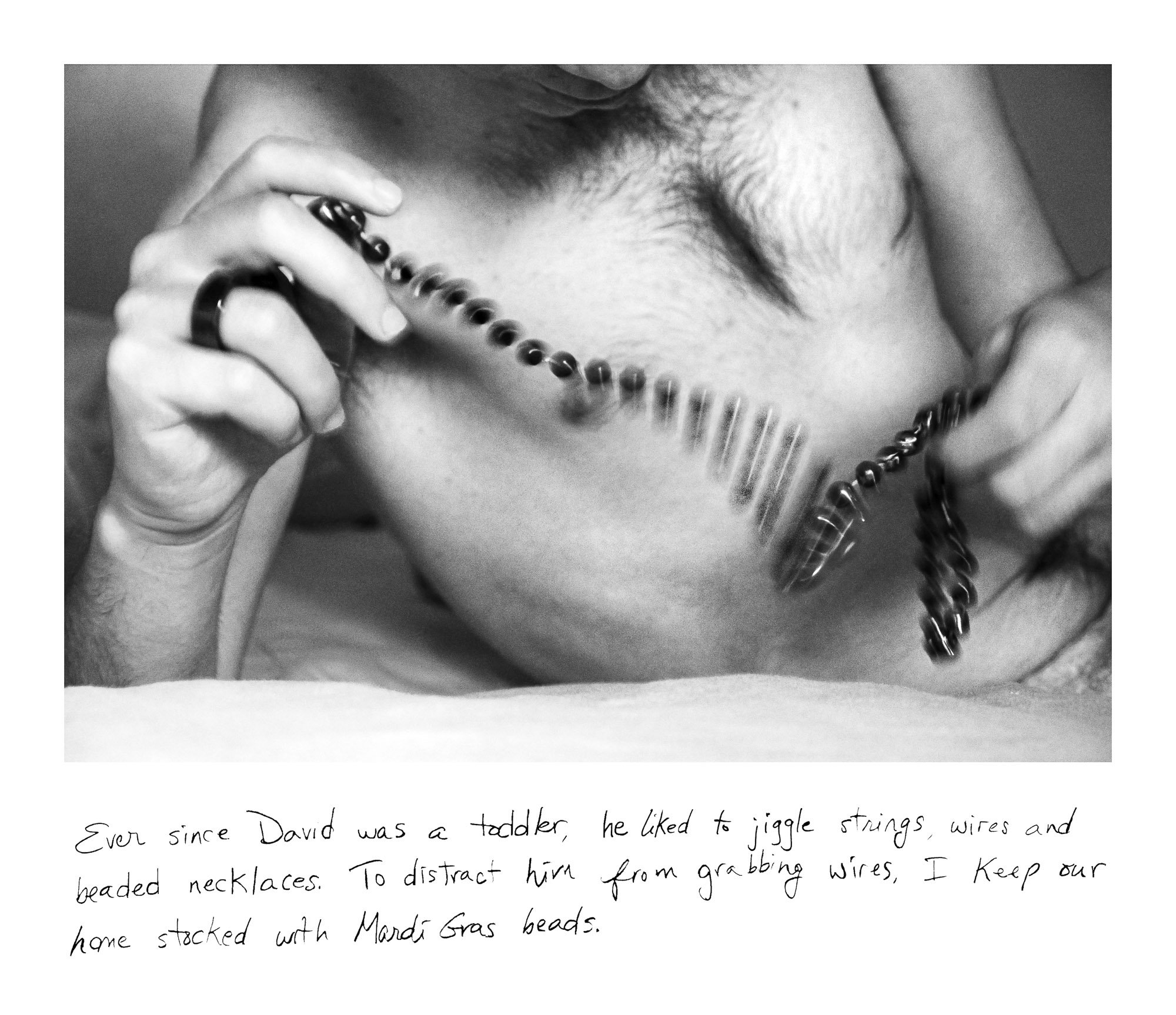

David lights up when someone he feels special about visits. He shows affection by leaning in and touching us with his head. It’s the most beautiful thing to experience. When David is frustrated or disturbed, he shrieks or makes a grunting sound while jerking his body back and forth. For long periods, he’ll be off in his own world, playing with beads or sitting quietly. Lori and I like to joke and tease each other, as sisters do. When we do, it’s easy to see David understands our humor by the smirk on his face.

Lori is a rock. She is mentally and emotionally strong, exceptionally caring, and super smart. She’s equal parts student, guru, and lighthearted goof. In addition to David’s care, she is a life coach and spiritual mentor, working with parents whose kids face a range of issues from special needs to mental illness. She experiences the same emotions as the parents she works with. Shouldering the challenges of caring for David as a single parent is a difficult life.

Morning meditation

JTD: Wow, thank you for sharing all of that. You’ve spoken previously about negotiating consent with David, which I can only imagine would be complicated. What was that experience like both for you and him? How does his continued consent (or perhaps lack thereof, sometimes, if that happens) inform your work?

DA: Having David’s consent was important to me, but I didn’t know if he would respond. I asked him right after I asked Lori, explaining I would honor him and not do anything to make him uncomfortable and if he ever wanted me to stop, I would. At that moment, David stopped jerking his upper torso back and forth and did something he’d never done before. He leaned forward with his face close to mine, and stared into my eyes, holding the gaze. Then he smiled and resumed the jerking movement. Lori and I were in shock. I ended up staying a month.

With David’s demonstrative form of communication, I take my cues from his responses to my presence. I also look to Lori, if it’s a delicate situation, to know if I should back off . She’ll call out to me if he’s having a seizure so I can document the event. For the straight documentary element, I shoot in reportage, as I would for any project... with sensitivity and respect. There are vulnerable and private moments I’ve photographed that will never be printed or published.

JTD: Where did the title come from?

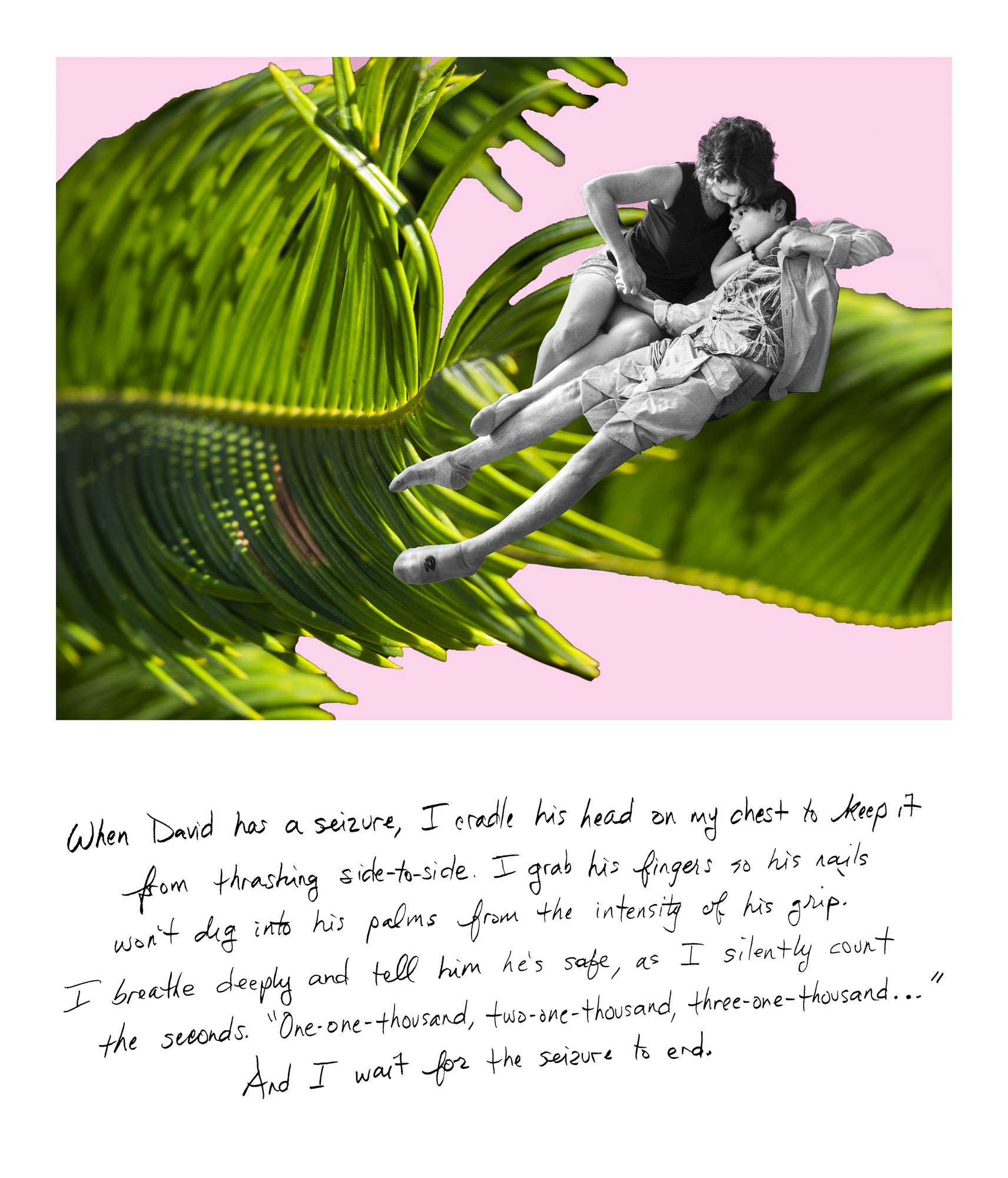

DA: Initially, the working title was Silent Buddha. In 2014, Lori gave a TEDx style talk titled My Silent Buddha, Wisdom from my Son. She spoke of his influence on her and how she came to accept his condition and their life together. I loved the title but, even though Lori and I practice elements of Buddhism, we’re not Buddhists and the scope of the story has a broader narrative. In one of the captions for this project, Lori describes how she cares for David during a seizure, as she counts the seconds beginning with “one, one-thousand...” This way of counting is common, creating a personal connection and inviting curiosity.

JTD: Some of your works are “straight” photographs, while others include other elements such as colored backgrounds or collage. Talk to me about your thought process behind introducing these other elements and what you hope they bring to the work.

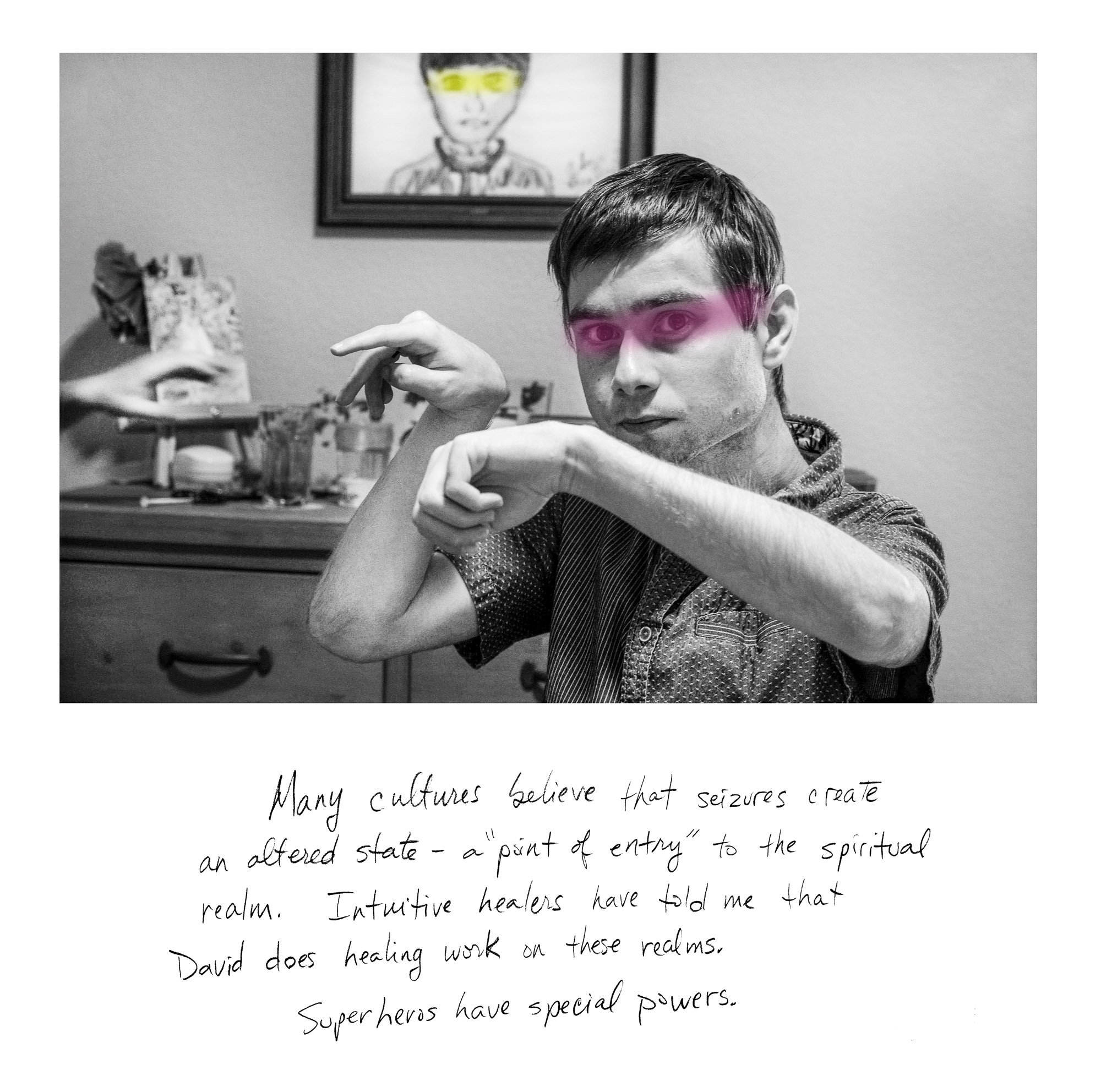

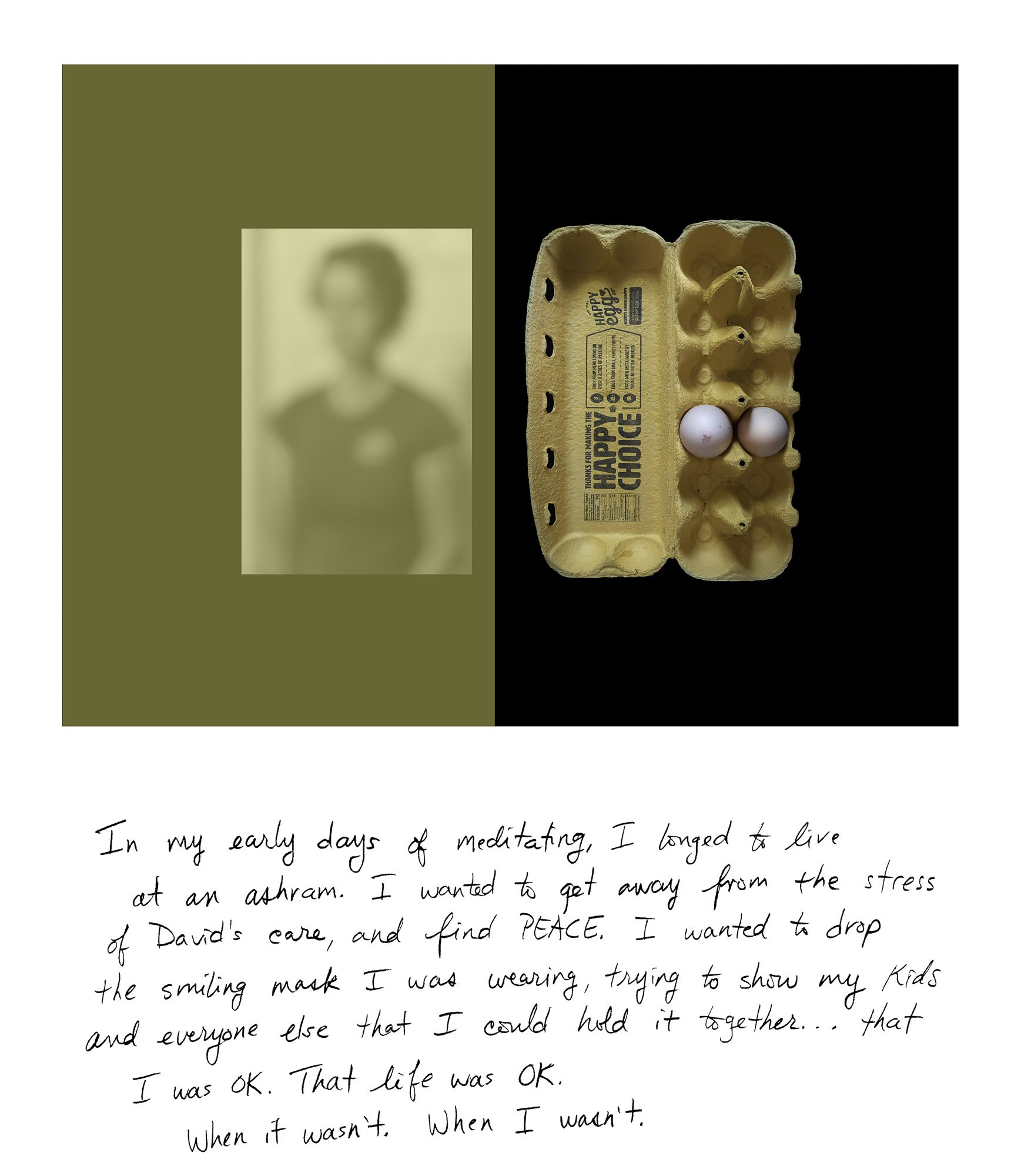

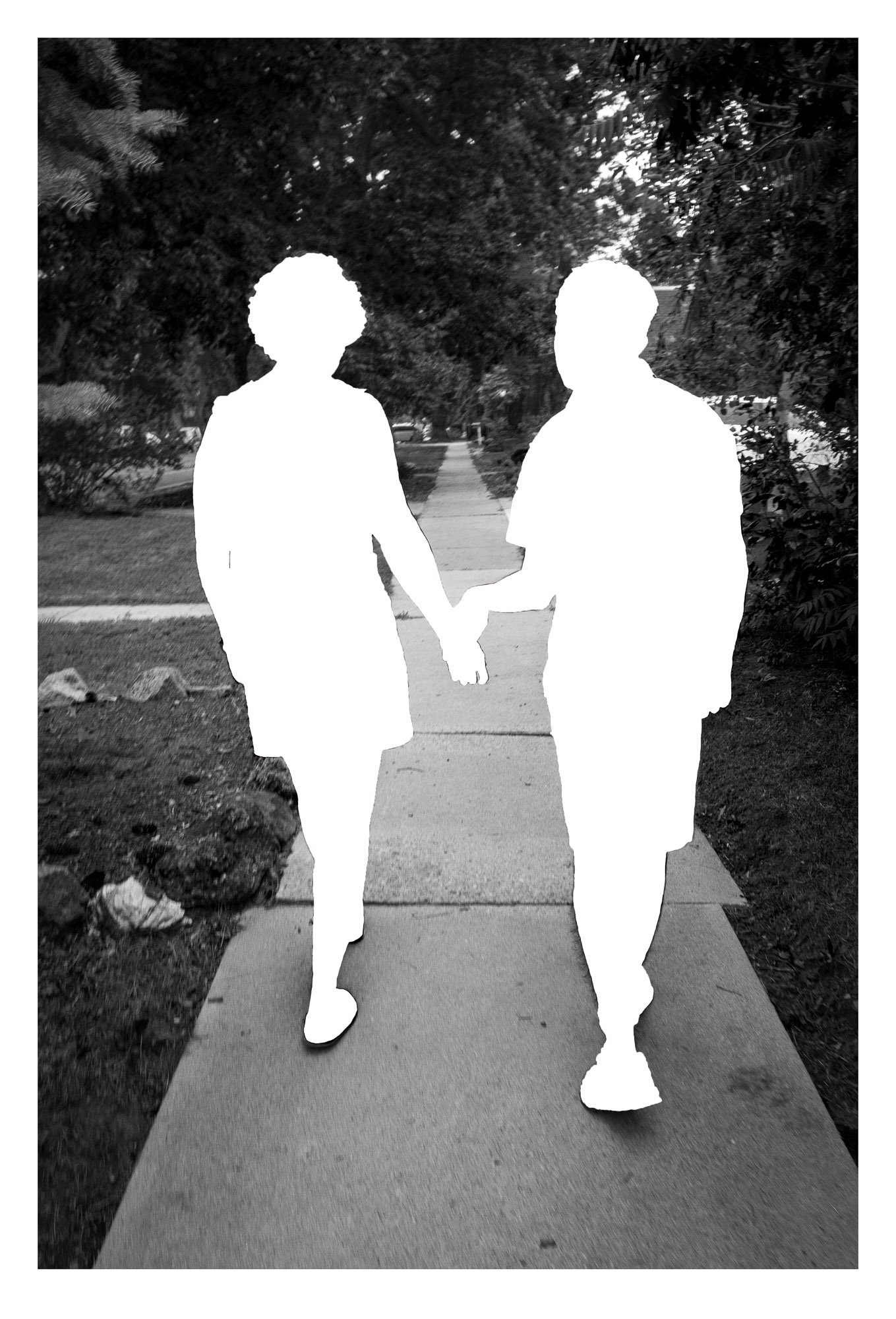

DA: The black and white photographs convey the hard, daily truth of their lives and are pretty straightforward, whereas the collage and photo-based images represent elements outside the realms of our knowledge and understanding. The use of color, diptychs, graphic elements, and collage hint at David’s unspoken perception of the world (visually, mentally, and spiritually).

As you mentioned, David has severe autism. There is a 70% chance that individuals with autism also have synesthesia, a condition in which one sense is experienced through another, such as seeing color when hearing a sound. I use color as is an indicator of this probability. Some intuitives have said David is a healer working on other planes. What does that even look like? How does he see the world? Since he was a baby, David stared off into light sources for extended periods. I’ve always wondered where he “goes.”

Constant presence

JTD: Alongside your photographs, as you mentioned, you’ve included text captions written by David’s mother, Lori. I found the text to be a very moving part of the work. What was your thought process around including text? It seems significant that the words come from Lori directly, but can you expand upon your decision to center her voice?

DA: Thank you, Jess, that means a lot to me. There’ve been a few iterations to get the work to where it is now, and it’s still a work in progress. Lori is the messenger and I am the witness. Over the years, she’s written raw, heart-wrenching essays about her experiences with David. The moment I wanted to make the project, I knew I’d include them in some way and the importance they would hold.

I was prepping one, one thousand... to exhibit at the Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome Foundation Awareness Day fundraiser last November. Education was part of the intent so we could raise funds and awareness. To get the full impact of what it’s like to be a lifetime caregiver and the one being cared for, I felt we needed captions. I coached Lori with specific questions until the captions felt complete. With no budget, I typed, printed, cut, and pasted each one on foam core then taped them next to each of the corresponding photos. Between groupings of photographs, I displayed Lori’s essays, fairly large, as part of the installation.

Viewers came up to us commenting on Lori’s experiences that moved them. Most were scenarios they could not fathom. I raced to find highlighter pens for attendees to highlight phrases that impacted them. By the end of the evening, all the essays and captions were covered in yellow. During the event, I realized the computer-printed captions felt impersonal and sterile. I asked Lori to handwrite the captions to create deeper intimacy for viewers. As it turns out, her cursive writing in an upward, carefree fashion reveals more of her personality.

Into this world

JTD: This kind of text treatment is part of a lineage of work by other artists; perhaps, most notably, Duane Michals, but also others such as Jim Goldberg and Jeffrey Wolin. And, to a less direct degree, Carrie Mae Weems or Philip Toledano. Do you view your work in conversation with any of these artists? Were any of them a direct influence?

DA: Great questions. I do and yes. It’s important artists to know whose shoulders we stand upon and to understand the obvious and subtle conversations within the bodies of work. The through line between our projects involves themes of social consciousness using text to tell a narrative in ways the photograph can’t do by itself.

I was most familiar with Duane Michals, having seen him speak at Medium Photo Festival in 2014. I revisited his work when we switched from type to handwriting. Other than that, I don’t look at the work of other photographers when creating. I want to keep a clear mind, free of influences (as much as a person can be).

Pairing text and image together happened by circumstance. It was an easy way to show my portfolio online and in-person for portfolio reviews, grants, and submissions. Initially, each photo had a caption. Over the past 5 months, I’ve had mentors and reviewers say different things about the captions: get rid of the text, the pictures speak for themselves, the text is important, and mix it up. I went with the latter. This gives the viewer a chance to rest with the narrative and feel it on their own. Choosing which images would or would not include text was a fascinating phase of shaping the narrative. I had some great coaching and, as Brad Zellar said in a presentation during Chico Hot Springs Reviews in Montana this past March, “Put it in their reach, not their laps.”

Another day

JTD: one, one thousand... seeks to raise awareness about Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome and has both an educational and an activist component. Could you talk to me about these aspects of the project? In what ways do you use your work for education or advocacy?

DA: The idea of this project is to expose the hidden impact life-long care has on a caregiver and the one being cared for. It is also meant to be used as a vehicle to educate the public about LGS and raise funds for its treatment and cure. LGS is a rare type of epilepsy, and although there is significant funding for epilepsy, there is very little that is specific to LGS. Only 1-2% of individuals with epilepsy are diagnosed with LGS. As noted, it is incurable and is resistant to most seizure treatments. So, except in rare cases, individuals with LGS experience seizures for the duration of their life, along with co-existing disorders such as autism, sleep disorders, and global neurological impairment. They are also at risk of dying as a result of a seizure.

In the summer of 2021, I learned about the LGS Foundation and reached out to see if the work could help in any way. The answer was yes, and we began shaping Silent Buddha (the working title) for their Annual International LGS Awareness Day Fundraiser that fall. Lori spoke about how LGS has impacted David’s life, her experiences as a single mom providing his round-the-clock care, and how she sustains a spiritual practice that keeps her going... all to a tear-filled crowd. I spoke about making the project and of course about Lori’s perseverance and unbelievable strength. Most of the attendees didn’t know many details about living with LGS and the hardships of being a full-time caregiver. They shared with us how impactful it was to view the photographs and read Lori’s writings.

More than one in five American families provide in-home care for a loved one. These caregivers are often advocates and care coordinators. I’ve seen the emotional impact caregiving has had on my sister. According to the National Library of Medicine, “Caregivers are potentially at increased risk for adverse effects on their well-being in virtually every aspect of their lives, ranging from their health and quality of life to their relationships…” The broader intention in sharing this story is that caregivers feel less alone in their struggles.

Along with exhibitions and talks by Lori and myself, we are exploring programming ideas for education and community engagement which could include lectures and panel discussions. In addition to LGS, topics may include neurodiversity, long-term family care, and psycho-spiritual health for the caregiver. On a side note, I donate a portion of each print I sell to the LGS Foundation for research.

While you sleep

JTD: What do you imagine as the culmination of this project? Are you working towards a book or exhibition?

DA: I’m prepping for a solo exhibition at the University of Colorado, Fulginiti Pavillion for Bioethics and Humanities, just outside Denver. The exhibit will run for six months beginning this September. What’s amazing is that the work will be shown in tandem with an immersive exhibit on the geography and workings of the brain. one, one thousand… will bring a personal perspective showing what can happen to an individual and family when the brain misfires.

I’m excited about a recent partnership with a technology innovator. With funding, we will develop software and programing for augmented reality, virtual reality, and hybrid technology that simulate the social/emotional experiences of a caregiver and the one being cared for. The end goal is to nurture compassion and understanding. If all goes as planned, there will be a traveling exhibition to reach communities nationwide. My sister and I have just begun the fundraising stage to make it all happen. Our fingers are crossed.

I envision a book, but not yet. There’s more work to be made.

JTD: In addition to this project, what are you currently working on, and what is on the horizon for you as an artist?

DA: one, one thousand... is sweetly consuming me right now with three group exhibitions held across the country this summer. Lori, David, and I attended the artist opening at the Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, Colorado last week, which was special for us. In July, Lori will travel with me for two more openings, Exhibition Lab Exhibition at Foley Gallery in New York City and the Member’s Exhibition at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester, Massachusetts.

I’m excited to teach teenagers The Art of the Photographic Capture at the Los Angeles Center of Photography at the end of July. In addition to my business printing for and mentoring fine art photographers, I continue to develop programming and host industry professionals for FORUM with Pasadena Photography Arts (PPA). In the fall, I’ll have the honor of presenting my work. Last but not least, I continue to work on my road trip series, edge of an [American] dream, and foreseeable cache. One of my photographs from foreseeable cache will be released as a Klompching Edition in July.

Thank you, Jess, for these thoughtful questions and recognizing one, one thousand... for the CENTER Social Award Honorable Mention. You are helping us reach our objective by leaps and bounds. I am forever grateful.

JTD: Wonderful, thanks so much Debe!

All images © Debe Arlook