Q&A: COURTNEY COLES

By Keavy Handley-Byrne | October 22, 2020

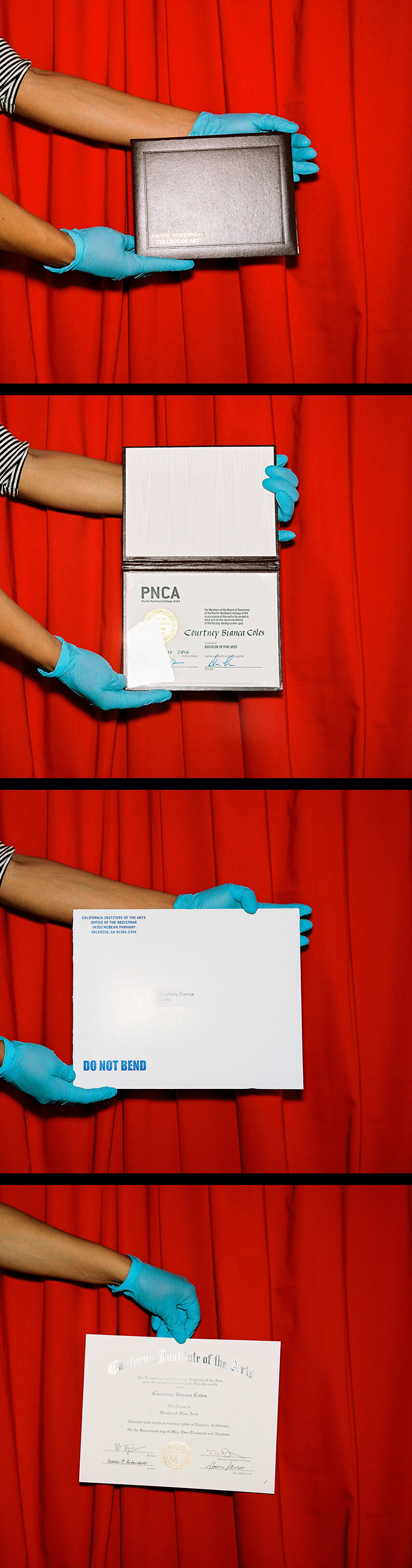

Courtney Coles is a photographer and visual storyteller based in Los Angeles, California. She is a cofounder of To The Front, a traveling gallery show highlighting the work of women and nonbinary photographers in the music industry. She holds a BFA in Photography from the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, Oregon, and an MFA in Photography and Media from the California Institute of the Arts. She has been a visiting artist at UCLA, the Pacific Northwest College of Art, and the New York Film Academy. Her work has been published in numerous publications.

Keavy Handley-Byrne: Hi Courtney! Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me about your work, I’ve been really looking forward to it. We can start at the beginning: how did you get started using photography as your main tool as, in your words, a visual storyteller?

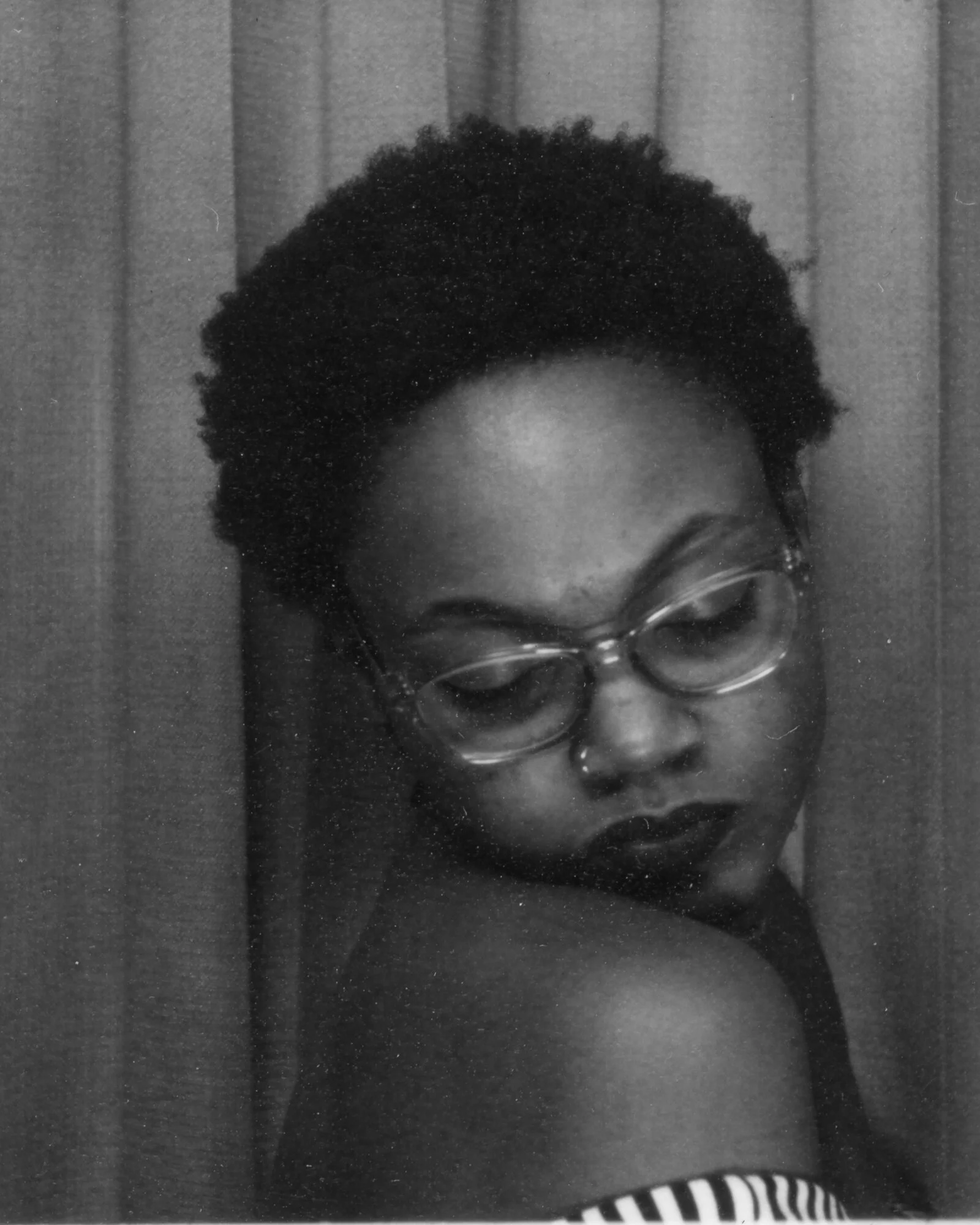

Courtney Coles: First and foremost, I'm an observant person. I can't remember a time when I wasn't looking at someone, trying to remember the way they carried themselves and how they reacted to situations. My parents always had some sort of camera, be it a VHS, a polaroid or a compact 35mm. They documented me and my siblings on family vacations and birthdays and those photos lived in photo albums. Wanting to keep my own albums, I started bringing a disposable camera to class field trips and on the last day of school. What started as a way to remember friends grew into a way to keep my own alternative family album.

KHB: You have been based on the West Coast for the better part of your career. How do you think that living on the West Coast, and particularly in California, has informed your work?

CC: Living in California has greatly influenced me in ways I didn't know were present until I moved to Portland for my undergrad. Almost immediately I was homesick for the sunshine which at the time I was sick of. I found myself looking for things that reminded me of home and spent a lot of time making playlists that were the soundtrack to my homesickness. My photographs are warm and inviting, like the California sunset, but that warmness is tinged with loneliness, which is simply my depression seeping through. Los Angeles is beautiful, but Los Angeles is lonely. That can be said about just about any city anywhere in the world, but I've never felt so out of place yet at home with my sadness than I do in the California sunshine.

KHB: In your series Public Confessions, you’ve used photo booths as your main method of creating the photographs. How did this project start?

CC: Like most of my projects, it started as an accident. Prior to making the first strip that started this journey, I sat in photo booths (both digital and film) with friends. It was a quick and fun way to document our time together and I taped the strips to the wall of my apartment. At the end of 2013 I was gearing up to move back home from Portland and my thesis mentor told me that the first year after college is the most difficult because that's usually when people stop making art due to whatever reason. She encouraged me to lean into it and to not get discouraged because it happens to everyone. It's hazy trying to figure out when exactly I made the first strip: in December in Portland or in January in Los Angeles, but it started as a way to document that first year. There are a lot of strips where I'm flashing the camera and while that gesture is something to be expected of me due to how often I did it, that was an extended version of my undergraduate thesis in where i spoke about growing up in the baptist church and how my body was never mine but something to keep pure for my future husband. The dismissal of purity and this idea that I didn't have autonomy of my own body infuriated me and so in my 24-year-old brain the easiest way to challenge that was to flash my breasts. It was my way of saying my sexuality wasn't up for debate.

As the years grew, I kept seeking out the booth and a few months after getting into graduate school I realized I was sitting in front of an audience of (n)one, seeking answers to questions I never asked out loud. It was in the reflection of the glass where the lens sat that I saw that I was looking into a mirror, trying to make sense of who was staring back at me. The photo booth saw all of my sins and didn't judge me for it and instead loved me wholly. I came out to the photo booth before I came out to myself and now that I’m living loudly out of the closet, the photo booth grew to be a safe space for me to be my true self. Oftentimes in predominately cis, white and heterosexual spaces. In all my photo making and researching, I’ve come to the conclusion that the photobooth was and still is one of the few public safe spaces for queer people to express themselves. If not for naught, it’s one of the few public spaces I have been able to express myself.

KHB: What do you feel was gained through the limitations of the photobooth as your photographic tool?

CC: The fact that I wasn’t in control of what the print would look like. I used to keep the fact that I'm an overachiever to myself but a few of my teachers caught onto that. In undergrad the then head of the photo department kept telling me that it’s okay to not be perfect and I took that as her singling me out. It took years for me to realize she was telling me to be gentle with myself and let go of control. In grad school the dean of the photo program called me out in class when I objected to turning in a work-in-progress for a midterm grade. he said, “I know you’re an overachiever, but no one has anything completed now and I just want to see where everyone is with the project.” I am many things but subtle isn’t one of them. I’m sure I’m quoted somewhere saying aspects of my work are subtle (because they are), but as a person? I am not subtle. i like to think i am, but if anything my face gives it all away. The limits with the photobooth forced me to let go of what I think the print should look like and lean into it.

KHB: You also have a series of photographs titled At Home Confessions. Can you talk a little bit about this work? Is it a continuation of the series begun in public spaces?

CC: This summer I had tentative plans to visit lesbians bars in the country and analog photobooths that were recommended by friends. Due to the pandemic, plans have changed. I had no desire to end “public confessions'' because the work didn’t feel complete. I’m still searching for answers to questions I'm not cognizant of but with the closure of bars and restaurants, my monthly confessions were at risk. After voicing my sadness about the premature ending of my project, my friend Carly put to words what I had been mentally mapping: set up my own home photo booth and use a 35mm camera as the medium. After playing around with the 35mm for a couple of months, I invested in a polaroid onestep+ and that’s currently the camera I'm using.

KHB: You have photographed the intimate space of the bedroom as well, often placing your viewer in, or at least very near, unmade or partially made beds. Can you talk about this space in the context of your Confessions work? How do the two relate?

CC: I love bedrooms. Actually, I love homes. It's the bedroom that I've always been drawn to and it's mainly because the bedroom is the most private room in a home where the owner is able to express themselves with no limitations. I've had some critiques in the past where someone commented saying, "well, actually, the bathroom is also a private room" and while they aren't wrong, when you're at a house party or a friend has you over for dinner the bedroom isn't on the list of places you're hanging out in and the bathroom is open for visitors to use. This of course changes when the owner lives in a studio apartment or shares their living space with other people and so a guest is invited to hang out in the bedroom, but that doesn't change the fact that a bedroom is a private little hideaway where you can really see someone's true personality. the first iteration of this project was titled "make room for me" and that grew to "invite me into your life" and now it lives as "bed(rooms)". The theme is the same, though: I was invited into someone's personal space and was shown their heart. the project started with the owners sitting on their made beds and eventually grew to unmade beds, which are beds I have slept in; it’s a nod to Tammy Rae Carland’s “lesbian beds.”

May 2015, Baker City, Oregon. Image Courtesy Courtney Coles.

KHB: You’ve also photographed your home and family, and your relationship to your family seems to be a big and important part of your work. Has photographing your mother changed your relationship with her? If so, how?

CC: In the beginning it did. I've always observed her both up close and from afar. Everything I learned about in church, she was the exact opposite of. We were taught that women were supposed to be submissive and that men were the head of the household, and my parents shared responsibilities equally. The older I got the more I learned that she pursued my father which, of course, was a major no-no in the eyes of the church. Despite being this amazing Christian woman, she was still very much her own person and I loved that.

Shortly after I bought my first film SLR, she was in the hospital. I think I put off seeing her for maybe a day, but I went one day after work with my sister. I brought my camera with me and I photographed her asleep in her hospital bed. The details from that evening are hazy, I mentally checked out. I knew that one day I'd want to have a memory of seeing my mother in the hospital so without processing what was in front of me, I photographed her. It was the first moment in December 2007 that I was able to slowly fix a relationship I thought I damaged. When I moved to Portland she drove up with me and I photographed her sleeping in my bed. Those first photographs were my way of preserving my memory of her. Truth be told: I was terrified of her dying and not having any photographs of her. That’s still the case today.

Mom, Courtney Coles

KHB: You are also a cofounder of To the Front, a traveling art show and collective for women and non-binary artists working in the music industry. What was the impetus for starting the collective?

CC: I've always had a difficult time separating my time in the music industry from my studio practice and a lot of it had to do with not believing there was a distinct difference. The way I'd photograph a musician was how I'd photograph a longtime friend. When Erica (Lauren) and I started to the front, we were both heartbroken. I wish there was a hopeful answer to where this momentum came from, but we were both heartbroken and were tired of waiting for anyone to say yes to us so we did it ourselves. We asked our friends Dani Parsons and Carly Hoskins if they wanted to get a gallery with us for a night and that was the beginning of it. We just wanted one night where we took our photographs off the internet and into the real world. That quickly grew to what it is now and we are constantly learning.

In a way, to the front is the answer to “where are all the _________ artists in the galleries?” Instead of waiting for a gallery to cherry pick us, we looked to our friends and friends of friends and simply asked, “hey, wanna show your work with us?” and it’s been the most transgressive and organic thing.

KHB: How has the collective and your experience within changed your practice?

CC: My art practice has slightly changed in that I'm hyperaware of all the new eyes on me and my work via what I've done with To The Front and I'm not sharing new work online. I love that collective with my whole heart, but I also make personal work that if you’re introduced to me via our collective, will make you do a double take. There's something about entering into my world when it’s a self-portrait/self-reflection (sometimes nude) or a photograph of my mother. it’s another to enter into my world and all you know is what you’ve seen via to the front. I can't talk about one without spotlighting the other because I believe both worlds are in constant communication.

KHB: Courtney, thank you so much for talking with me about your work — I look forward to seeing what you do next!