Q&A: Claire A. Warden

By Hamidah Glasgow | November 28, 2015

Claire A. Warden (b. Montreal, Quebec) is an artist working in Phoenix, Arizona. Claire's work explores intersecting ideas of illusion, control, identity, and performance. The constructed photograph is integral to her arts practice. She received her BFA in Photography and BA in Art History from Arizona State University.

Claire’s work has been exhibited in the United States and abroad including: solo exhibitions of Mimesis at the Center for Fine Art Photography in Colorado and Art Intersection in Arizona as well as group exhibitions at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Rayko Photo Center, Sous Les Etoiles Gallery, Division Gallery in Toronto, Agripas 12 Gallery in Jerusalem, Galería Valid Foto in Barcelona and Students’ City Cultural Center Gallery in Belgrade. She has received a residency through the Alfred and Trafford Klots International Program for Artists in Léhon, France, an Individual Artist Grant Award supported by the Creative Capacity Fund and the Contemporary Forum Artist Grant supported in part by the Nathan Cummings Foundation Endowment. She has been named LensCulture's Top 50 Emerging Talents in 2014, Photo Boite’s 30 Under 30 Women Photographers of 2015, a Critical Mass finalist (2015) and a finalist for Photobook Melbourne Photo Award (2015). Her work has been featured in Real Simple magazine (2014), The HAND Magazine (2014), Common Ground Journal (2014), Prism Magazine (2015) and the forthcoming annual publication by Diffusion Magazine (2015). Claire just completed an Artist-in-Residency at Art Intersection in Arizona.

Hamidah Glasgow: This series is quite different from your earlier work, tell me what lead you to create the current series Mimesis?

Claire A. Warden: Before I started work on Mimesis, I was working on a series entitled, Salt: Studies in Preservation and Manipulation. In this work, I used the subjects and methods of the natural sciences as a vehicle to explore the intersections of knowledge, control and manipulation. Through my research, I became particularly interested in the way that colonization would use botanical illustrations. I was intrigued by the way European colonizers of the Old World would approach a new environment by creating a survey of the natural surroundings to identify the edible, herbal, medicinal and otherwise useful plants and natural resources as well as those to be avoided. I was deeply inspired by the intentions of botanical illustrations as a method to understand and control one’s environment while maintaining a symbiotic relationship with place and identity. However, in Salt I wanted to show the futility in attempting to preserve and index an organic specimen that can only exist in a liminal state. I would find live plants and submerge them in a salt-water solution. This paradoxical mineral, necessary to sustain life—yet, if the delicate balance is outweighed, can extinguish it—would preserve the form and color of my collected plants while encapsulating it in its crystalline structure. After working on this series for three years, I had come to a point where the work began to feel complete, and the questions I developed with the Salt series were, perhaps, the tipping point for me to address some more personal experiences and questions. Simultaneously, a curiosity about the limitations of photographic materials—both physically and representationally—and the possibilities of what a photograph could be, lead to Mimesis.

HG: With your description of the Salt series I see the connection between Mimesis in that they both deal with what you called, “a vehicle to explore the intersections of knowledge, control and manipulation.” The image, Number 57, Gradient seems to be a strong example of this, would you agree?

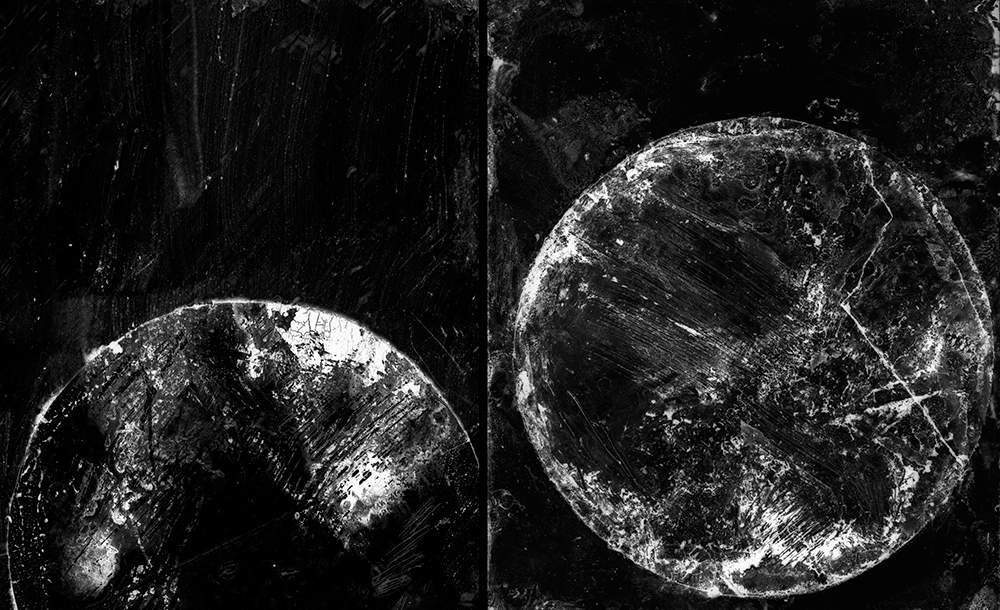

CAW: I think you are right about No. 57 (Gradient). I created that piece to speak about representation in photography, particularly regarding skin tone. The three center mid-tones of the gradient scale were made by cutting sections from three different self-portraits using varying light sources and exposure times. In this piece, the variance in the representation of my skin tone is as important as the constructed highlight and shadow, made with mark-making, that complete the full gradient scale.

HG: Was there a moment where you first realized what the series would be about? In other words, did this start in a different way and then morph into what it is now?

CAW: When I begin a new series, I have some idea of what I want to express but it usually becomes clearer as I continue to produce work. When I realized the visual effects and conceptual potential in using saliva with developed film to create a sort of self-portrait, my intention with the series became clear very quickly. For Mimesis, an important part of my art practice includes sharing the artwork publically and engaging in critical dialogues surrounding the issues that are layered within the work. This allows me the opportunity to step back from the work and see it from another perspective. I love that this series allows for such broad interpretation. This engagement also brings awareness to the various approaches in the work that are communicating more clearly with the viewer.

HG: Tell me more about sharing the work publicly? What format does this usually take? Is sharing the work early in the process specific to this body of work or a way that you prefer to work in general?

CAW: I don’t generally share work when it is early in the process and I actually worked on this series for about a year before I started sharing this work with a greater audience. However with Mimesis, sharing the work as soon as pieces are finished has helped me to articulate some of the complex issues within the work. I think the best way to truly share this work is in an exhibition of the series. The exhibition size of the work is large enough to create experiences that can envelope a viewer. An important aspect of sharing the work in exhibition form is that it also allows for an artist talk, where I can be present and discuss the work. Since this work is not clearly representational, I hope people can view my work in person, connect with it and then come to my artist talk to hear about why I make these images. That is when we can have the best dialogues about this work.

HG: How do you define agency in photography? Who are your primary sources of inspiration for both artistic and philosophical inspiration?

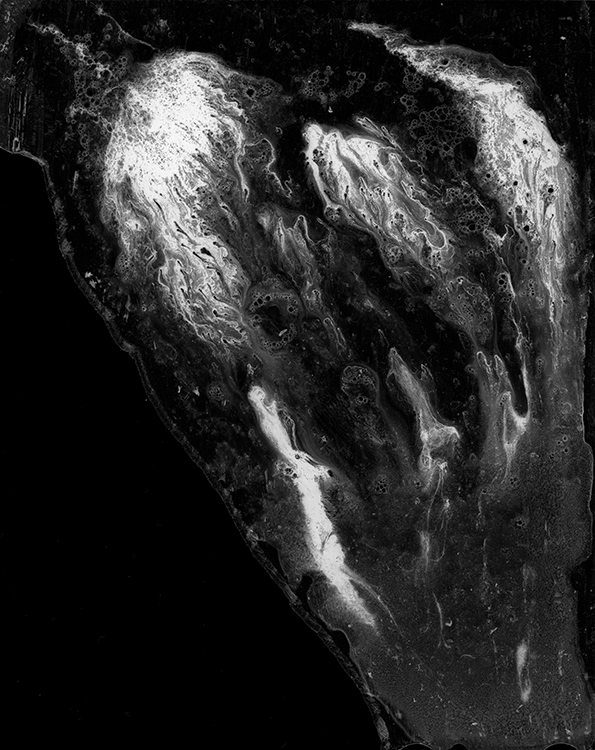

CAW: My understanding of agency, in terms for sociology, is our innate capacity to think, make decisions and act. An artist’s agency is inseparable from the act of making a photograph. It is so much a part of any art form but perhaps it is more easily forgotten when it comes to photography. However, the framing, composition, space, time and mechanical/technical decisions are so much a part of the artist and all their life experiences up until that very moment. It is almost impossible not to think of agency in photography as agency in any other art form—with a full awareness of the artist behind the artwork. In the case of Mimesis, the creation of a single negative can be extended over the course of months or years. The agency in my photographs is an essential aspect of creating and understanding this work. When I look at this work, which contains representations of the biologic and socio-cultural in a way that feels balanced and complete, I see more a self-portrait than any photograph that represents my physical likeness.

When making this work, I try to remain very present and conscious of the things that are influencing me at that moment. I find inspiration in revisiting personal experiences, reading about sociologic and historic texts—like identity formation or colonization—as well as artworks and philosophies across mediums. I am inspired by artists who explore the materiality of their medium, like Marco Bauer, Alison Rossiter and Jeff Cowen. I am inspired by artists who explore identity and social hierarchies like Lorna Simpson, Kara Walker, and Barbara Kruger. I am inspired by artists who explore spirituality and human experience like Mark Rothko and Duane Michals. I am also inspired by Brancusi’s approach to form as its essential nature; Mondrian’s theosophy regarding truth and the abstract; Motherwell’s receptiveness to the creations of the unconscious.

HG: When people don’t understand the concept of your work because not everyone has been asked the question, ”What are you”? or can relate to the underlying issue, how do you explain the work to them?

CAW: Constantin Brancusi said in an article about his artwork in the 1950’s art journal, Prisme des Arts, “It is only fools who could say my works are abstract; what they are categorizing as abstract is in fact the most realistic thing possible, for reality is not the outer form but the idea, the essence of things.” This quote resonates with me. However unforgiving the quote may be, it strikes a chord in regards to a general impression of abstract art. Essentially, artwork that departs from the clear representation of outward appearances does not equate to artwork devoid of intrinsic meaning, and this can be difficult to grasp. The conceptual aspects of Mimesis are incredibly important. In many ways, I use visual abstractions in the work to address the abstract nature of identity and identity formation. The work originates from such a personal place and because of that I do not expect that all people will understand the concepts embedded in this work completely. However, I think this work has multiple points of entry and people are going to see it through the lens of their own experiences. Some of these concepts may resonate in a way that is more universal. One of these concepts, in particular, is explained through my photographic process.

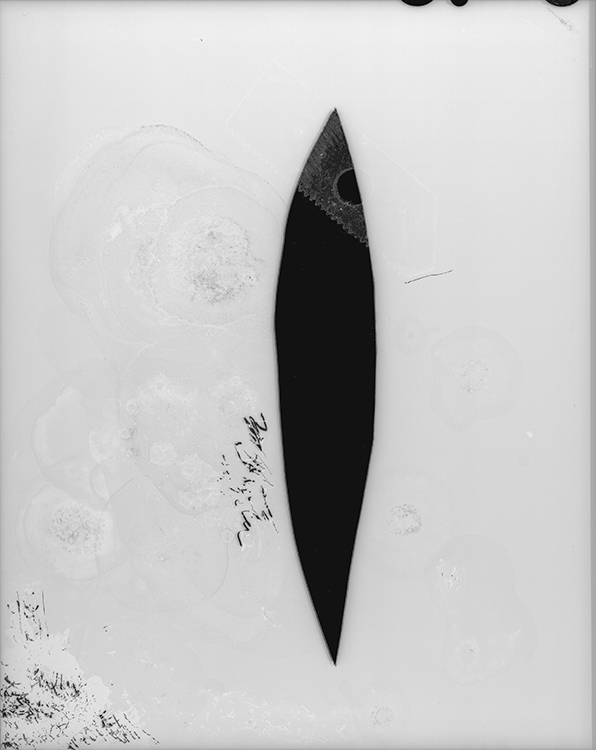

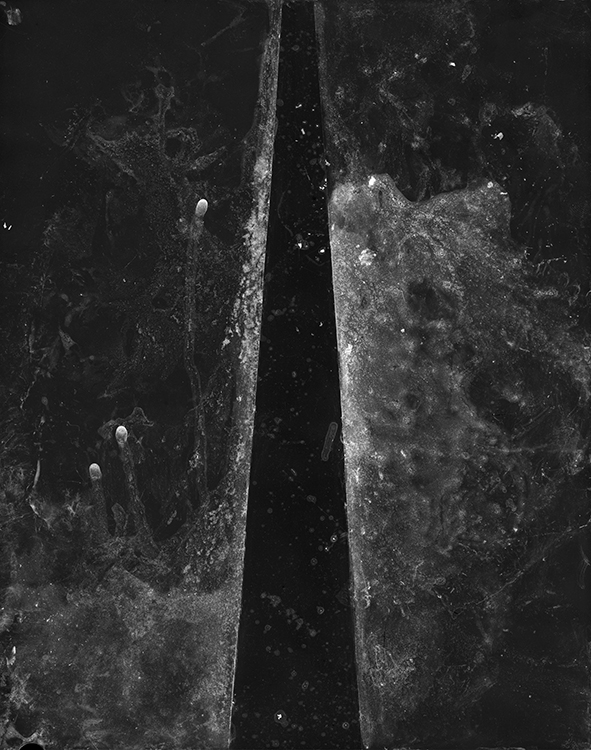

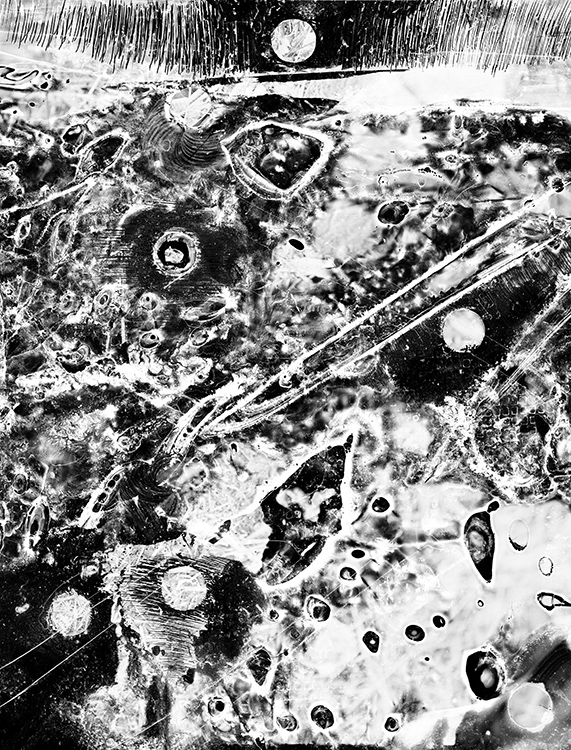

I use saliva as part of my photographic process in conjunction with mark-making to manipulate the surface of medium- and large-format photographic negatives. Saliva contains—among other things like DNA—digestive enzymes, which react chemically with the silver gelatin layer of the film. The organic patterning is a result of the saliva etching through the gelatin and leaving the silver halides and biologic matter behind. Once this process is complete, I react to the patterning on the negative with simple manual tools to create informed symbols and patterns. When I interact with or react to an ‘etched’ negative, it is often an additive or subtractive process. I do this in reference to a sociological concept called impression management. It is essentially the editing we do on a daily basis to manage the perceptions that others have of ourselves by sharing or limiting certain information about ourselves. We all do this, and it changes all the time depending on our environment.

HG: This relates to the Mimesis statement when you talk about the performance of identity. Can you speak a bit more about this performance aspect of identity?

CAW: The performance aspect of identity is the seamless interactions between the different groups of people in our lives—family, partners, long-time friends, colleagues, professional acquaintances, etc. In some cases these are comfortable roles that are easily slipped into, like the relationship of a parent and child, while others may be carefully practiced and prepared for. To an extent, developing an awareness of this performance lead me to consider the question, “what are you?” more deeply. Not matter what the social situation, if I were to answer the question in a more satisfying way by saying, “I am a naturalized American” or “I am Canadian” this response is rarely adequate to the person asking. Inevitably, the next question would be some form of, “What are you, really?” In these moments, the clear shift toward my outward appearance—beyond my control and dictated by my genetics—can feel like an establishment of social hierarchy, regardless of whether the experience is positive or negative.

HG: Your work explores who gets asked the question, What are you? Which is very much a conversation of who gets asked this question and who doesn’t. This is often a difficult conversation.

CAW: You are right; it is a difficult thing to explain. When I share this work and discuss the question, “what are you?” and my experience being asked this question, the response can be shock and disbelief. Some people are asked this question throughout their life, and some people are not. I don’t know if a person who has never been asked this question can completely understand but I do hope they become aware of how the human mind strives to index and identify and how certain knowledge and perceptions can lead to control and social hierarchies. Because this work is photographic, it beckons the question, “what am I looking at?” To me, this question reaffirms that photography is the perfect medium to make this work and have this discussion.

HG: Is there an image that is your favorite from this series? Why?

CAW: I am excited by each piece in a different way. Working from one piece to the next, my explorations and questions deepen but no one is more important than the previous. Older pieces in the series that I have lived with for some time feel very comfortable while some new pieces, made in recent months, feel fresh and exciting. Since each piece can take so long to produce—one month to over a year in some cases—I am elated when a piece finally feels complete.

HG: What’s next on your plate either in your work or your life?

CAW : Continuing to make new work for Mimesis is my main focus. There is still so much to explore there. I want to continue to engage in these challenging dialogues and for the work to continue to gain exposure by traveling the series. In my life, I am filled with joy to say that I will be marrying the love of my life—and talented artist—David Emitt Adams next summer. There are so many beautiful and exciting things on the horizon.

All images © Claire A. Warden