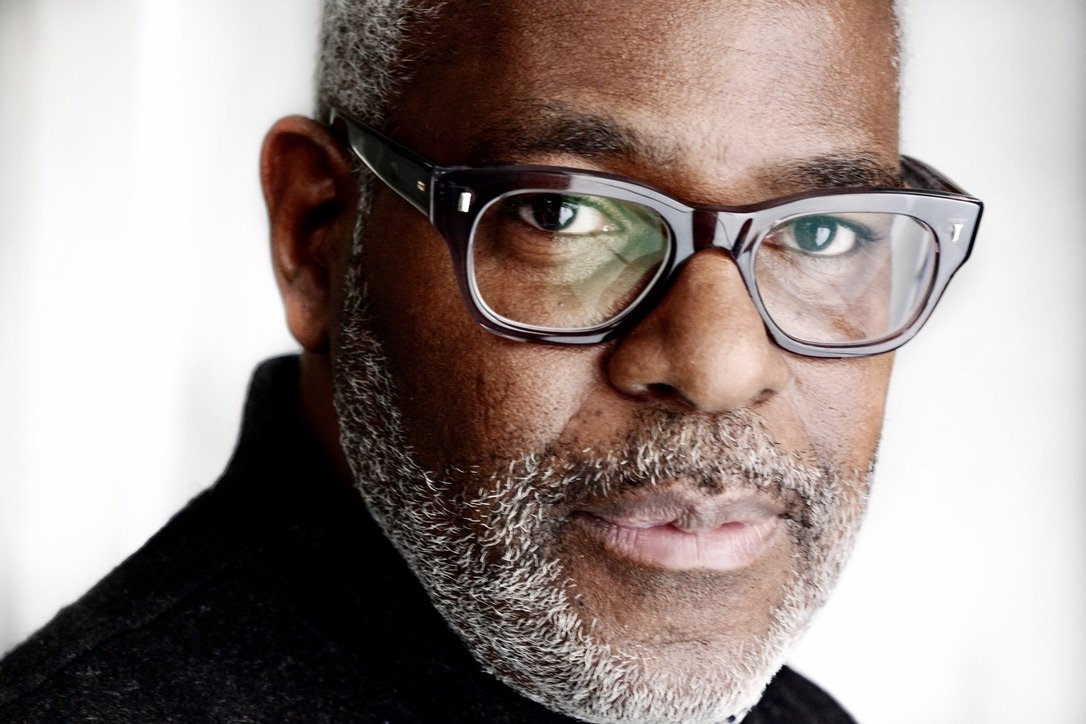

Q&A: Charles Guice

By Hamidah Glasgow | September 15, 2022

Charles Guice is an art advisor, curator, mentor, and writer. An accomplished arts professional with extensive experience, conversant in the diverse role of photography, he has been instrumental in advancing the careers of numerous leading contemporary artists, such as Erika Diettes, Priya Kambli, Kambui Olujimi, Hank Willis Thomas, and Carrie Mae Weems. As a gallerist, Guice placed works in prominent private and public collections throughout the United States and abroad, including the Brooklyn Museum, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the High Museum of Art, The International Center of Photography, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The first black member of The Association of International Photography Art Dealers (AIPAD), joining and exhibiting over a decade ago, he is the co-founder of Converging Perspectives, an online initiative promoting timely, critical, and in-depth discussion of contemporary photography from an international perspective. Guice has written articles and essays for publications such as B&W, Contact Sheet, and Nueva Luz, among others; and in 2020, he served on the planning committee for The Center for Photography at Woodstock’s online symposium, Race, Activism and Photography, for which he developed the core programming. Guice is currently serving on the Board of Directors for 10x10 Photobooks, and has previously served on the Boards of Trustees for The California College of the Arts (CCA) and The Museum of The African Diaspora (MoAD).

Hamidah Glasgow: Welcome, Charles, and thanks for spending time with me. You have impressive background. Tell me about your trajectory as a collector and a gallerist in the photography world.

Charles Guice: Thanks for that introduction, Hamidah. Well first, I think I have a passion for the arts that came from my parents, and definitely from my father. He was trained as a draftsman, and he wanted to eventually become an architect. But as a black man starting a family in Chicago in the mid-50s, even as a draftsman no one would hire him. So my grandfather already had a well-established plumbing business, and my dad joined him, becoming the city’s youngest journeyman plumber.

But my dad was also an artist. He was an illustrator, a watercolorist, a photographer, and a sculptor. He even once learned how to grind and polish a mirror for a large reflecting telescope, which he built by himself.

My parents’s interests in the arts inspired me early on. I have the earliest memories of my parents taking me and my older sister to museums. I know I wasn’t three years old then, because my younger sister hadn’t been born yet. I remember that I would draw, I would color, and later, because my mother loved opera and classical music, I would sing and play instruments. We had paintings on the wall, and sculptures around the house, and I honestly thought that was the way that everyone lived; surrounded by art.

HG: I know we’re talking about your career as a photography dealer, but did you ever think about becoming an architect like your father had wanted to become?

CG: I did. But that was after I had already studied psychology, sociology, and English. My mother had been a social worker, and I thought that I wanted to become a psychologist. My wife, Jill, went to graduate school in San Francisco first, and she was studying to be a psychotherapist. Years later, when it was time for me to go to graduate school, I realized I had changed my mind. I seriously considered studying to become an architect instead. But by that time I had already been in the workforce for more than a decade, and I was earning a fairly good wage. In those days, architects weren’t paid very well. Eventually I decided against it.

HG: So what did you do instead?

CG: I was working in senior management in healthcare, and I actually considered getting my master’s in public health. I enjoyed it then and it paid extremely well. But in the end I decided against it as well and earned an MBA instead. This is also the time when I started to collect as my parents once had.

HG: Well, regarding collecting, it seems that your parents were your role models.

CG: They were. The idea that some people had nothing on their walls seemed so foreign to me. My parents collected mostly paintings, but they also owned other artworks like sculpture, and even African masks. I had already purchased some art on and off, but it wasn’t until after graduate school that I started collecting photography.

In June of 1993, I saw Carrie Mae Weems’s work for the first time at The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. I definitely remember the impact that Carrie’s Kitchen Table series had on me. Later in the same year, I discovered Roy DeCarava’s photographs, too.

It’s not that I was new to photography. I started taking photographs when I was a teenager, largely 35mm black-and-white, and I was very serious about it, to the point that I once considered becoming a fashion photographer. Anyway, when I saw Roy’s work, I felt akin to his. And, believe it or not, I didn’t even know he was black for some time. But I loved his photography.

Sometime after that, during another visit to SFMOMA, I saw an exhibition featuring four contemporary female photographers. I don’t remember the other three, but I fell in love with Marta María Pérez Bravo’s work. This was well before most galleries were online, and in San Francisco, almost no one knew her name. It took me a while to find out more about her.

HG: You spoke about Roy DeCarava’s work. DeCarava received a Guggenheim in 1952; published a photobook with Langston Hughes, “The Sweet Flypaper of Life”; and opened a gallery, A Photographer’s Gallery, in the same year. Tell me about that.

CG: Right. So I discovered Roy’s work in 1993, the same year I saw Carrie’s at SFMOMA. I don’t remember how I came across it, but most likely it was in print. His photographs were so artistic and formally rigorous. I remember feeling almost overwhelmed by Roy’s photographs. I just loved his eye, and the way his images captured breathtaking beauty in even the most ordinary moments of life.

I started reading articles and collecting whatever catalogues and monographs I could find. There wasn’t much then. So I started writing to him, and I found a phone number and I left messages. For a long time, I never heard back. But for me, Roy was the most distinctive photographer in the world.

Then finally, I had a chance to speak with Sherry, his wife. It may have been 1995. Because the following year, Roy’s retrospective opened at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. I first saw the exhibition at its stop in Chicago, followed by three more venues around the country. And then I finally had a chance to meet and talk with him in LA. What an honor! Later, I went to see him in Brooklyn, where he lived, and I had an opportunity to spend more time with him, and to talk about his craft.

HG: So you started collecting photography. But then you decided that you wanted to change your career and to become a dealer. How did you go from healthcare to the arts?

CG: By early 2001, I had decided to leave the healthcare industry. I shouldn’t admit this, but I actually toyed with the idea of buying a vineyard and opening a winery first, and after that I considered becoming a coffee roaster. My wife at the time shot both of those ideas down—by reminding me how terrible I was with growing plants—and she pointed out my love of photography and talking to people. By the end of that year I’d become a photography dealer.

Anyway, while I enjoyed the work of a variety of artists—for example, Ruth Bernhard’s work was the first photograph I collected—I knew I wanted to specialize in the work of contemporary black photographers. I had already gained some expertise from my research in the eight years since I first encountered Carrie’s and Roy’s work. And I still remember the day when I discovered Deb Willis’s first two books, Black photographers, 1840–1940: an illustrated bio-bibliography, and An illustrated bio-bibliography of Black photographers, 1940–1988. Deb’s work provided definitive proof that black photographers had contributed to the medium from the beginning.

HG: Willis wrote “Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present” as well, right?

CG: She did. Where her illustrated bio-bibliographies were mostly lists, her later books, including Reflections in Black, created a full narrative of black contributions that had previously been omitted. I really owe a portion of my success directly to Deb’s research.

To become a specialist, particularly on the work of black photographers, I knew I needed to develop a broad understanding about the history of photography and not just about black photography specifically. And I actually don’t believe such a thing as “black photography” exists. There are, however, phenomenal photographers who are black. In addition to Deb’s books, I spent months and months in both public and university libraries, researching independently, and then building a personal library of hundreds of books and catalogues.

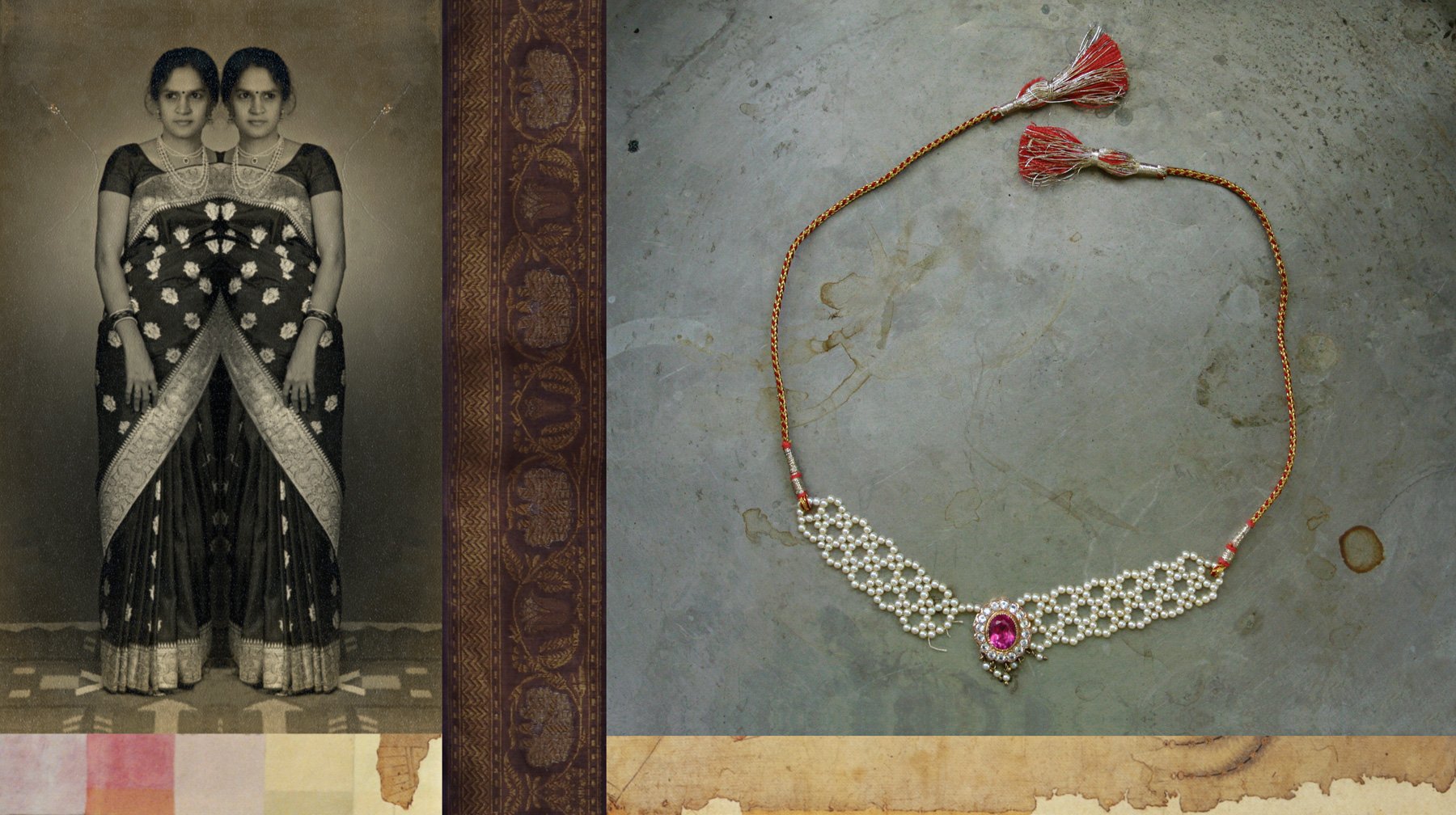

And as a dealer, I had the privilege of representing a group of extraordinary artists, first with black photographers such as Kambui Olujimi, Hank Willis Thomas, Shawn Walker, and Carrie Mae Weems. Carrie Weems! And sometime later, I expanded to a more diverse range of photographers, taking on artists such as Erika Diettes, Jessica Ingram, and Priya Kambli. I was able to place my artists’s works in prominent collections throughout the United States and abroad. It was only after a serious illness that I was forced to close my business.

HG: I know that you had a stroke, and it was a debilitating one that left you physically impaired.

CG: Yes, I did. And I’m still dealing with that. But before that, I had fun. For example, when I first called Shawn Walker and told him that I wanted to represent him, he immediately said yes. He’s since told me a number of times that I was his first dealer.

I met Hank while he was in graduate school, and he was upfront and said “if you need a photographer, I’m your man”. So I started representing him shortly after he graduated, and later added Kambui as well as they were creating their first animated film called Winter in America.

After it premiered in San Francisco at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, I told them we should create a small edition and sell the film. I still recall when Hank asked “how?” So I developed a limited edition with slipcase, video and book, which I placed into private and public collections. I also published a trade book—their first—which was available separately.

And representing Carrie was something else. For example, I was able to place her work with the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. And I premiered new work of hers, including her series Roaming, and coordinated exhibitions of her work during a critical period in her career.

HG: I know you’ve become a mentor and advisor. Who are you working with now?

CG: In a number of ways, I’ve always been a mentor. I have always believed that to be a good dealer, I needed to be there for my artists; to support them and to advocate for them. And I hope I did that. I also consulted with other photographers that I didn’t represent.

But, specifically, just before my stroke in 2014, I started working with an artist who lives in West Sussex in the U.K. I’d met Mahtab—Mahtab Hussain—at FotoFest in Houston. At the time, he was preparing to roll out an updated website, and I offered to review it. Before long, we began talking weekly, sometimes even daily, to discuss his upcoming show at Autograph ABP and his work in general. That stopped abruptly with my stroke.

It wasn’t until months afterwards that we started talking again, which was exceedingly difficult because I was still suffering with my speech. Anyway, even before my stroke, Hannah (Frieser) and I had talked about developing a long-term mentorship program, eighteen months to three years in length, and specifically for photographers. Because any artist working on a book or an exhibition needs that length of time. We named our initiative Converging Perspectives, and Mahtab officially became our first long-term mentee.

HG: Has it been successful for him, and the both of you?

CG: Well, Mahtab has repeatedly acknowledged my impact on his career. We worked closely together on his first solo exhibition in London, and on several of his books. And recently, I worked with him again on his first sculptural piece, Did We Make a Mistake Coming Here?, which was exhibited at MAC (Midlands Arts Centre) in Birmingham, and just closed last week.

I also began working with a number of other artists, including Gesche Würfel, a German-born visual artist who is based in the U.S.; Haley Morris-Cafiero, an American-born, self-avowed “provocateur who uses a camera,” who’s now based in the U.K.; and Martín Weber, a Guggenheim-winning photographer and multimedia artist from Argentina.

When we moved to Woodstock, after Hannah was named executive director at CPW—then formally called the Center for Photography at Woodstock—she asked me to meet with each of the artists in CPW’s artist-in-residence program. WOODSTOCK AIR is a program specifically dedicated to support lens-based artists of color, who typically spend four or six weeks in Woodstock. I met with each artist individually to discuss their work, provide critical feedback, and guide them on their professional practices.

Woodstock is a small, predominantly white town. And CPW is an organization run by a staff and board of directors that is mostly white as well. While maybe not the ideal situation, I took on mentoring the artists, because I felt I could really make a difference for them. I met with most of them for a two or three hour session each, but also worked with a few of them, such as Dannielle Bowman and Rachel Liu, for an extended period, sometimes even several months or longer.

HG: And is it right that you work with most artists free of charge?

CG: Well, there is a reason for that. I have a friend, actually two very close friends, a couple; Susan Ehrens and Leland (Lee) Rice, whom I’ve known for more than twenty years. Susan’s a brilliant photo historian, and Lee is a Guggenheim award-winning photographer, teacher, and curator.

When I lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, Lee and I would go to Yoshi’s, a jazz club, and among other things, we would talk about photography for hours. We still do, even though I’ve long moved away. So imagine if he’d said, “okay, I’ll mentor you, and that’s a hundred dollars an hour?”

I charged some photographers early on, but eventually I stopped. It ran against what I considered to be my role, my place here. To teach, and to leave something behind; my knowledge. And it shouldn’t be the artists who are charged for everything. In fact, Haley has just started a mentorship program for British women over the age of 35. And it will be free to the photographers. I can’t take credit for her program, but maybe I helped to inspire it? I don’t know.

HG: I know that you have some opinions about portfolio reviews in general. Would you share those thoughts with me?

CG: Ah, the elephant in the room, right? I started [participating in portfolio reviews] almost twenty years ago, and the number of nonwhite photographers, particularly black artists, who attend continues to be embarrassing.

I’ve attended reviews where I was the only nonwhite reviewer, and not just for a year or two, but many times. And the real issue is that the majority of portfolio reviews are organized by people who don’t seem to notice that the room is all white: rooms filled with white reviewers and white reviewees. If there are participants of color, they’re almost exclusively of Asian or Latin American descent. Year after year, major review organizers publish a list of reviewers, a panoply of square boxes, and they’re basically filled with white faces. It's simply astonishing.

HG: It sounds like you were raised differently.

CG: I definitely was. I was fortunate to have been raised in a community where I grew up with people from all over the world. My parents never distinguished the differences between ethnicities or skin color—those of my friends, those of their own friends, or my own. And obviously, they realized they were making a choice.

My father’s best friend, Brian, was a white Chicago policeman. Looking back, that was unique in itself at that time. Their friendship lasted until the day Brian died. And my mother’s best friend, Gail, was a woman who happened to be white and Jewish. (My best friend then, David, was Gail’s son). I was fortunate to grow up surrounded by people from different countries, people from different ethnicities, different skin colors, and different religions. It was only when we moved to the North Shore, the suburbs north of Chicago, which was then a predominantly all-white, upper middle class community, that I truly understood that some people considered others—like myself—different.

So, fast forward, when I started participating in portfolio reviews, it surprised me that there were so few—if any—nonwhite reviewers or reviewees. It took a while to notice because while I obviously see it, I still don’t immediately distinguish skin color. Why should I? But eventually, at some point, you realize you’re the only one there. Some years ago, I went to an opening of Carrie’s (Carrie Mae Weems) in Beacon, New York, with a friend of mine who happens to be black. Carrie was at the American Academy in Rome at the time, so she wasn’t there. Shortly after we arrived, Tim remarked that aside from her work, we were the only blacks in the room.

HG: How do you think the lack of representation impacts the artists’ experience?

CG: A black curator, who’s also an artist, once told me that he had attended a portfolio review as a reviewee before and given the fact that there wasn’t even a single black reviewer, said he’d never return. Another reviewee, who was born in China, but raised in the U.S., was told by a (white) reviewer—a curator—that she should probably pursue exhibitions “at Chinese community centers”. Despite the fact that her work is contemporary and relevant, skip attempting to reach out to contemporary galleries or museums through their curators–Chinese community centers! And the issue isn’t really about skin color; it’s about the perception that the person on the other side of the table—or the lack thereof—understands where they’re coming from.

Because (nonwhite) reviewees talk, and because they then sometimes share their negative experiences, they don’t attend. So now it’s become a self-perpetuating problem. If you want to project that you have an inclusive line-up for your review, it’s probably easier to just select more nonwhite reviewers. It’s not that difficult. I could give you a list of twenty nonwhite reviewers without even thinking about it.

HG: Don’t you think things have changed recently, especially in light of the #Black Lives Matter movement?

CG: Yes, they have, but for all intents and purposes, just superficially. Arts organizations are still predominantly white—with white administrators, white curators, and collections that still heavily feature white artists. And intentionally or not, this places the organizations in an extremely weak position to build diverse programming or to diversify their collections.

So, yes, there has been a strong push for change since George Floyd’s murder, but without significant changes at an institutional level, any changes will likely be short lived. It’s exciting to see the increase of advancement opportunities for artists and curators that have emerged since 2020; however, all of these ethnic-focused programming and scholarships cannot fix a systemic problem unless organizations are open to much deeper changes.

HG: So where are the positive examples in the photo world?

CG: Well, you only have to look as far as the New York Times Portfolio Reviews, which have been such a breath of fresh air since the program’s inception. There were so many black reviewers the first time I went there, I literally lost count. There must have been dozens. And not just black, but reviewers and reviewees from different ethnicities, from different religions, and from different countries, featuring all these different skin colors. The system can’t simply be “broken”, because Jim (Estrin) and David (Gonzalez)—just two guys; one white and Jewish, and a Puerto Rican—got it right. Participating at a New York Times Portfolio Review felt like New York. But there shouldn’t be just one in a country as large as the United States. There have been some very promising shifts in recent years. Some organizers are making a real effort to change the complexion of their reviews, and I welcome that.

HG: What’s next for you?

CG: Well, earlier this year, I curated a solo exhibition by Doug Menuez that opened across two venues in Kingston, New York. And in April, I joined the Board of Directors for 10x10 Photobooks. Finally, Hannah and I are working on several projects for Converging Perspectives that we hope to announce shortly, and I’m also finishing up a couple of writing projects. It never stops!

HG: Thank you for your time and insights.

CG: Thank you!