Q&A: Cara Levine

By Rafael Soldi | February 11, 2021

Cara Levine is an artist based in Los Angeles, CA. She earned a BFA from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, MI (2007) and an MFA from California College of the Arts in San Francisco, CA (2012). Using sculpture, video, and socially engaged practices, she explores the intersections of the physical, metaphysical, traumatic, and illusionary. She is the founder of This Is Not A Gun, a multidisciplinary project aiming to create awareness and activism through collective creative action. Her work has been presented in one-person, group exhibitions, and participatory events in venues around the world such as the MOCA Geffen Warehouse, Los Angeles, CA (2020); Creative Time, New York, NY (2019); The Anchorage Museum, Anchorage, AK, (2019), Tenderloin Museum, San Francisco, CA (2017); Center for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv, Israel; Wattis Institute For Contemporary Art, San Francisco, CA (2012); and Kyoto Seika University, Kyoto, Japan (2006). Levine has participated in residency programs including Santa Fe Art Institute (2017); The Arctic Circle, International Territory of Svalbard (2017); Sedona Arts Colony, Sedona, AZ (2016); SIM Residency, Reykjavík, Iceland (2015); Anderson Ranch, Aspen, CO (2014); and Vermont Studio Center, Johnson, VT (2013). Levine is currently an associate adjunct professor in Fine Art and Foundations at Otis College of Art and Design and has worked in the disability arts community since 2011 in roles at various progressive art studios including the Exceptional Children’s Foundation, Inglewood, CA and Creative Growth, Oakland, CA. She organized the first annual Self-Taught Artists Fair with Public Annex in Portland, OR in 2017.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Cara, thank you so much for chatting with us.

Cara Levine: Thanks for having me!

RS: Maybe we can start from the back to the front. Your earlier work seems to have a playfulness and humor that is now replaced with, maybe not seriousness, but a confidence and efficiency that feels more resolved, more mature. Why do you think this is?

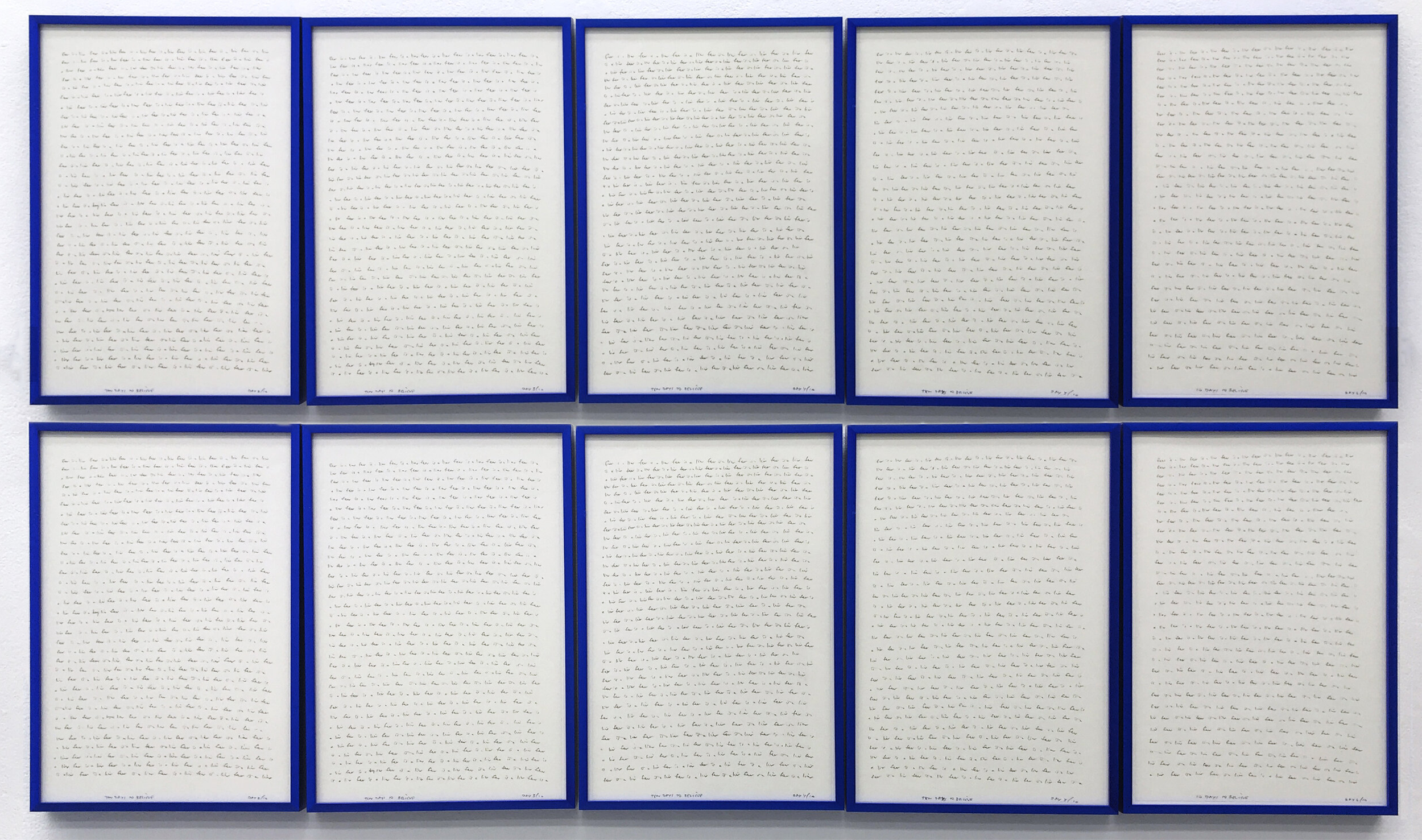

CL: It’s interesting that you see that and thank you for the reflection. I think this evolution is a result of multiple things: firstly, practice. I have been working at being an artist for as long as I can remember—committing myself to this path really from high school on—and in a concerted, or ‘professional’, way, for at least the last 10 years. I learned very early, that the practice demands a kind of rigor, patience, and discipline, that has to become habituated over time. Only through the doing do I become closer to understand what all the doing is about. I have a phrase written on a note on my studio wall: Practice begets belief.

Second, is urgency. As I’ve continued to make work, I feel a greater and greater urgency to make and communicate, see and feel, through artworks—this urgency helps me to hone in on what it is I really want to express through a work. It allows me to see the gold—a phrase my meditation teacher likes to use.

And finally, I think an aspect of trust or faith, has steadied, focused, and given confidence to my work. I believe with more and more certainty, that if I am feeling something, so is someone else—and with that, the access to art is bridgeable. I am much less afraid of failing than I once was, and conversely much more willing to take greater risks. I feel deeply committed to this thing of being an artist, and I want to show up as my fullest self.

RS: We’ve talked about a central tenet of your work being empathy, or an interest in embodying the experiences of others. Has this always being the case in your work and your life, or did this develop over time?

CL: It’s really both. Since my early twenties I’ve been exploring issues of embodiment, physical pain, neurodiversity, language, and trauma. [It’s a whole other discussion about childhood and upbringing that I think initiated the interest] But instead I’ll begin with a chronic ankle injury that began when I was about 20. I had multiple subsequent surgeries and many years of rehabilitation—that experience really widened my lens around access and ability. All the while, in college I was auditing courses on neuroscience and linguistics, while getting a degree in art.

Later, in graduate school, I began working with artist’s with developmental disabilities and the lens expanded even further. I felt, really for the first time, to be in a community of artists with expanded practices and understandings of the world, and I wanted to know more and more. I read profusely on neuroscience and neuro diversity and was more able to understand my own neuro divergent mind as a gift, rather than the hindrance I grew up thinking it was.

Then in 2014, I had an experience that, to continue the metaphor—broke the lens wide open, past of the point of no return—and led me to where I am now, wherein I understand empathy and embodiment to be fully immersive and powerful states of consciousness practice. I was debilitated with chronic migraines for about a year, and then another year recovering from all the treatments. In that time, my own relationship to pain, mortality, creativity, fear, love, etc, it all got reorganized. I came through feeling a much more profound physiological understanding of trauma in not only my body, but in all of our bodies, and in all time and place. I fear it can sound kind of “woo,” but it was this experience of chronic pain that gave me permission to step into the work I really wanted to make, to feel less fearful of the consequences, and to trust the process.

After this period, I felt more insistent about art being a critical mode of communication with the potential to be broader, subtler, and more nuanced and visceral than ordinary language.

I want to know how others experience the world. Each of us is like a facet on a diamond reflecting the sun—we have an inherent sameness that pulls me in, and a wild uniqueness that stretches my understanding.

RS: How do you negotiate making work about the experiences of others with your own identity, your artistic voice, your art career? As artists we manage a certain amount of ego inherent in promoting our own careers and seeking opportunities for exposure, attention, and growth in our practice. I'm curious about balancing those needs with the parallel interest in centering the lives of others in your work.

CL: This is a really interesting question and one that’s hard to pin down, but I think for me it centers around what I call the 85-year plan. I tell my students all the time, I’m on the 85 year plan, as an artist. For me, this helps tone down a feeling of needing to arrive somewhere—a destination that is always jumping further ahead. It also helps me remember that there is enough for all of us—enough opportunities, enough money, enough work. This does not always feel true or real, but it’s important for me to adhere to it to remain grounded. Also, I think my constitution is of someone who loves the work—I push the rock up the hill, and then there’s just another hill. So I push again. Though I am inching further along on this path, the pushing doesn’t exactly get easier, the rock doesn’t get lighter, the load and the terrain just evolve and so I just keep at it.

On the topic of balance—I try to involve myself in projects and communities I both care about and that inspire me. For about 10 years I worked in various ways with the disability arts community, be it as an instructor, artist in residence, curator, or advocate—though my role shifts, my commitment to furthering the art coming out of this community, doesn’t. As for me, working with this community brings me great joy, friendship, and inspiration—I find myself wishing I had a stronger presence there now.

I think, as for many working artists whose work is not traditionally commercial, the balance is an ever-shifting lever. I am an artist for whom being in and a part of the world, through activism, collaboration, and teaching, is essential. What part of my life pays the bills, connects me to community, and maintains time for studio work, are elements always in flux and recalibrating, but I like to believe they all contribute to my overall practice.

RS: Let’s talk about language. Text is an important part of of your work, either as a subject or as a formal tool. Can you expand on your relationship to language?

CL: Yes. I love language. There is so much to love. I believe, my reverence for it began the first time I immersed myself in a foreign language. When I was 18, I moved to a very small town in central Spain and worked as an apprentice for an artist, and taught English on the side. There’s a moment in learning language, where suddenly the dam breaks and the language begins to flow out of you—I remember feeling surprised and excited by it, like it sort of snuck up on me and my Spanish was suddenly “working.”. It was through this experience that I realized how connected culture and thought are to what we have access to express. There are concepts and feelings I cannot express in English that I can express through Spanish—it was a radical backdoor to new thoughts, ideas, and experiences!

I later was an exchange student in Japan and studied the language for about a year prior, but it has been much more difficult to sustain than Spanish. Similarly, while working at Creative Growth Art Center, I took part in some ASL courses, but have since lost most of it. How I wish to be multilingual!

I digress.

For me, a title is married to an artwork. It is like a quiet gesture of encouragement for the viewer of the work—pointing to how I intend it to be understood. Sometimes that understanding becomes more complicated or problematic through language, and sometimes it can offer a playful “aha” moment. Often a title, or language, comes before the form for me. It’s like an articulation of a phenomena, a tone, or an irreconcilability, that I then begin to look to form.

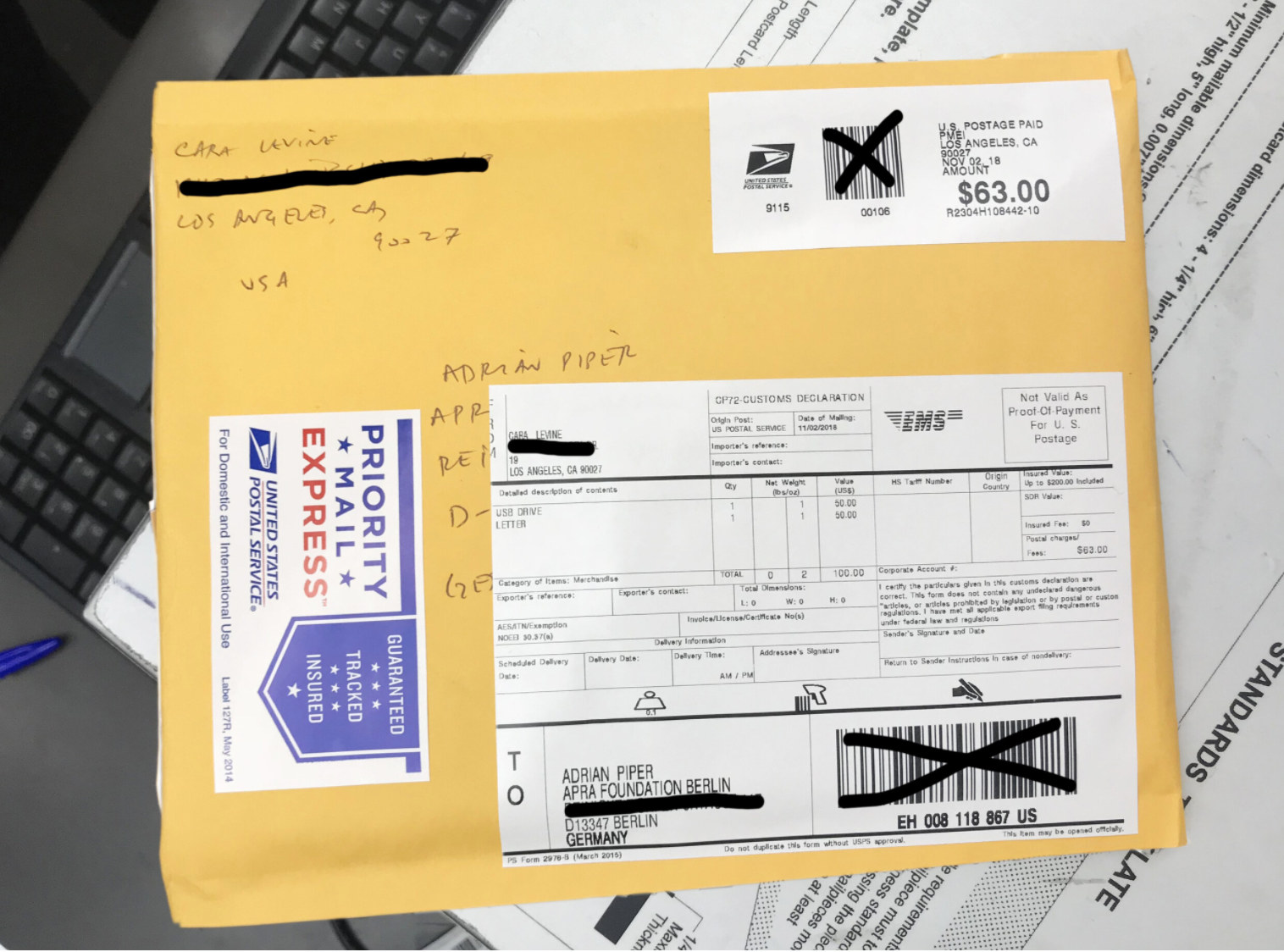

RS: On that note, I love that you write to your heroes! Do you recommend it?

CL: Oh yes, this is very important to me. We are each here, sharing time and space, for just a blink—what is it to collapse the societal boundaries that keep us separated? This reminds me of my neighbor Theo. I have a 7 year old neighbor, about 3’ and change tall, with wild curiosity. For months, he poked his face through the fence that separated our two backyards, and this week, he simply climbed over! Suddenly, Theo was standing right in front of me—a previously perceived boundary was, so plainly, crossed over.

I think my first letter—and all of them to some extent—have a similar sense of, “I didn’t know any better” attached to them. Like, why shouldn’t I be allowed to talk to directly to the person, I’d so long been gazing at through the fence? It takes a little bit of blind faith in both yourself and your mission to get over the fence.

Yes—I recommend it. Write with abandon! But, I implore you to respect the time of the person you are reaching out to and to have a clear reason and rational for your inquiry. These letters are distinctly different from fan-mail. I am compelled to write only when I think there is something that only this person might be able to provide in return—that’s why the letters come with relative rarity and high specificity. Also, you must know, the chances of gaining a reply are often quite low! But that’s ok; write anyway; it will open another door.

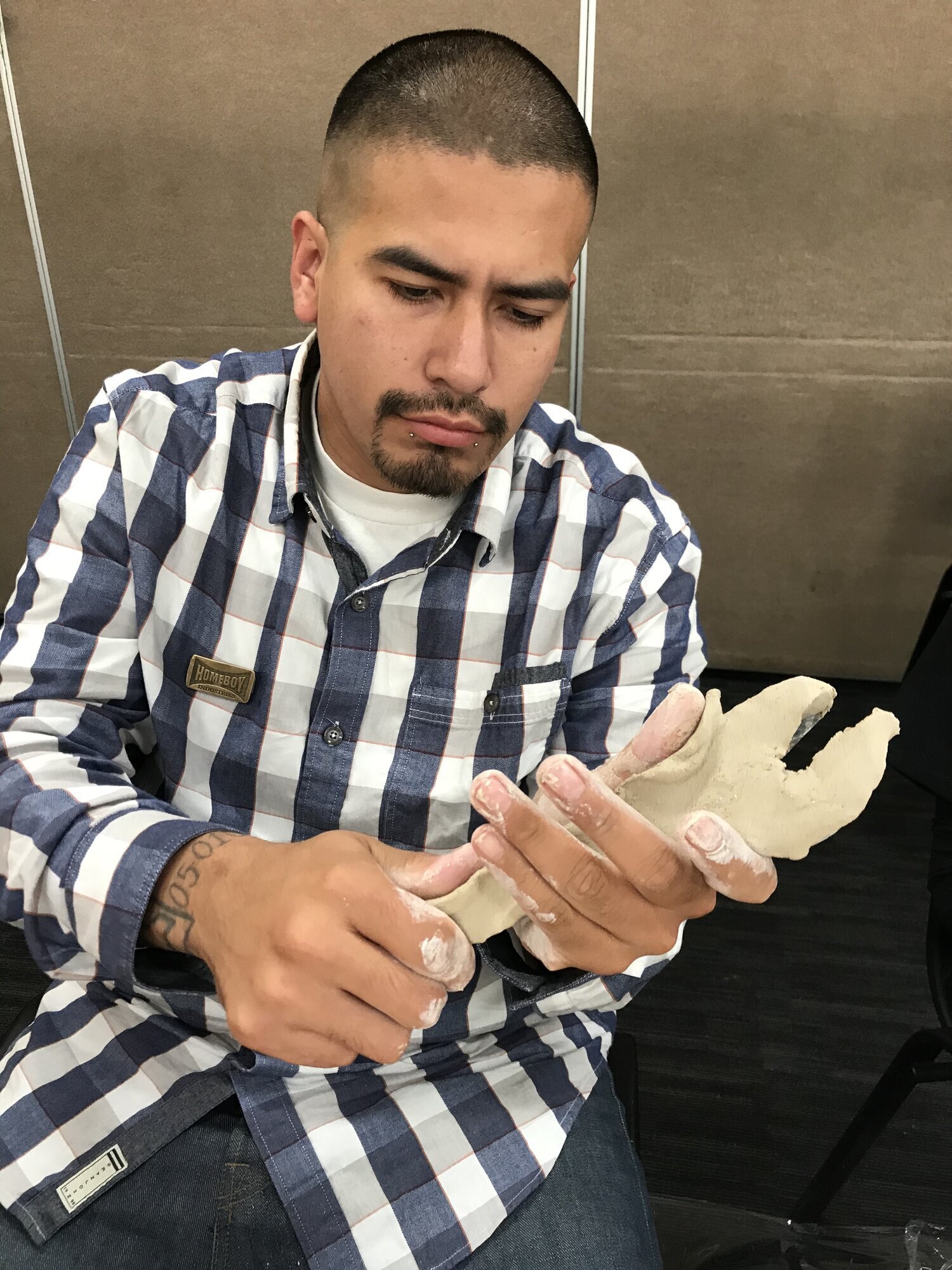

FREEDOM FRIDAYS / Project Knucklehead + Street Poets + This Is Not A Gun

RS: Impermanence and loss is another through line in your practice. This Is Not A Gun is such a massive and layered project. I’m not sure where to begin. Can you give us an overview of the project and some of the ways in which it has branched out? Where/how can people learn more?

CL: This Is Not A Gun, is definitely the most wide reaching work I have made. I could write and write on the work, but I will try to keep it concise. And, on that token, you can find out more about it on its project website, thisisnotagun.com as well as on instagram @thisisnotagun.

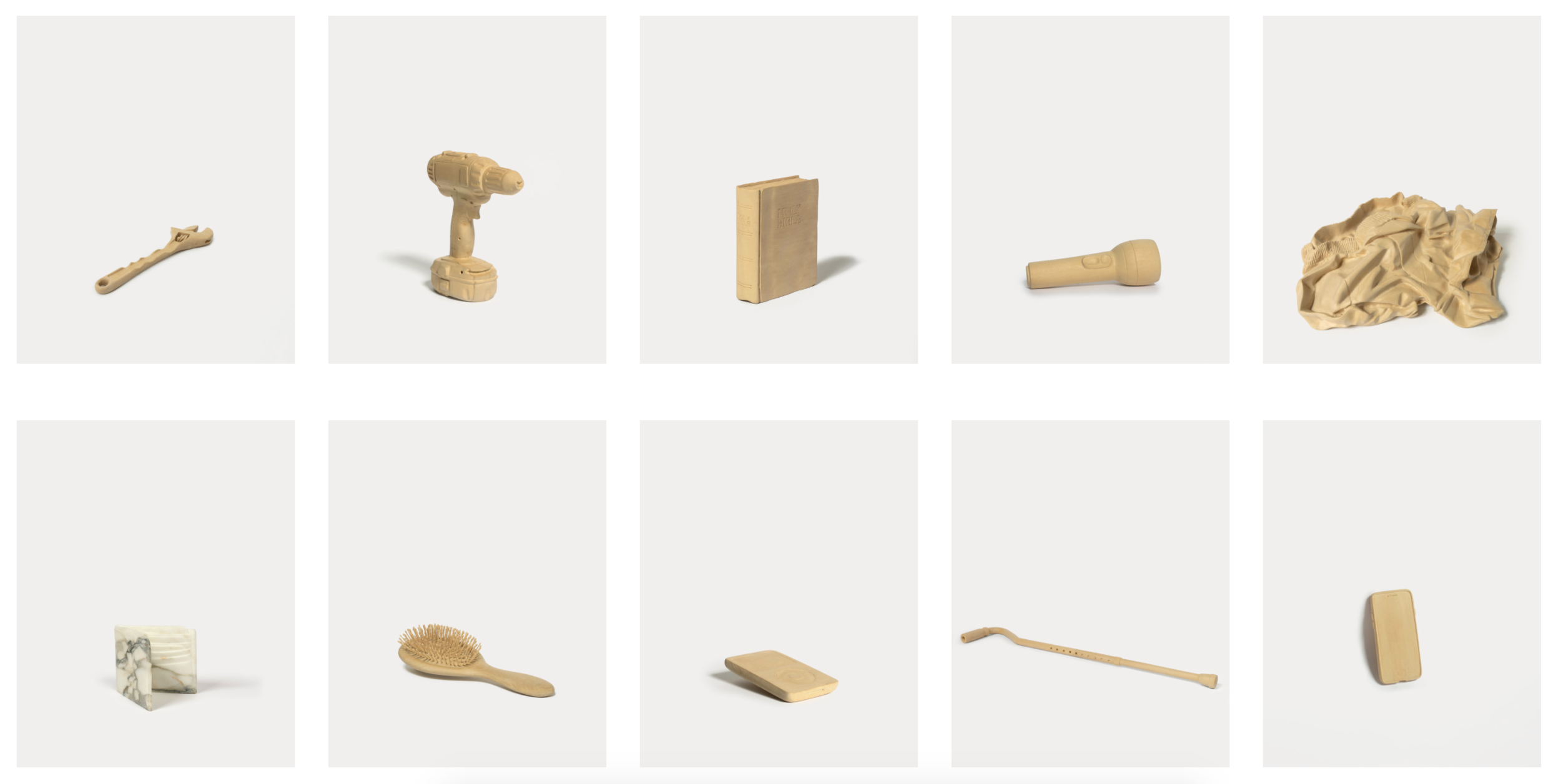

The project began in my studio in December of 2016, after I saw a list, published by Harper’s Magazine, of objects police had mistaken as guns in shootings of unarmed civilians since 2001. There were 23 objects on that list, including items like a wallet, cell phone, bible, set of keys, and a candy bar. Of course, I was shocked. I was also angry—angry that the list did not contain any other information. It did not contain race, age, ethnicity, time, place, or name. It is not hard to make the leap that the majority of items on this list would be attributed to Black men, who are much more likely to both be stopped and shot by police than white men in this country.

Nevertheless, I felt the need to slow way down and explore what this really meant. My first impulse was to begin carving these objects in wood—I thought if I could memorize each aspect of a flashlight, for example, somewhere along the way, maybe I would understand how a trained police officer could think it was a gun. While I carved, I put myself through a kind of re-education of the history of race in the U.S., listening to rhetoric and history on the topic. Quickly, I realized this process of making and contemplating race, trauma, and privilege, in the U.S., could benefit others beyond my studio.

In 2017, I began co-hosting ceramic based workshops of the same name. Each event brings together an intersectional participant body, and is led by facilitators across race, all invested in holding space for an otherwise rarely practiced, and often uncomfortable conversation. We make the objects in clay and dialogue about race equity, accountability, and cultural trauma. Since then we have led nearly 20 events in multiple states. I have had the privilege to co-lead with incredible artists like Angela Hennessy, Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, and Amir Whitaker, as well as work alongside organizations like Moms Demand Action, the ACLU, and Homeboy Industries. The events have taken place in all kinds of venues, from the Creative Time Summit, to student run youth activist gatherings on the steps of city hall.

We are currently in the process of creating more virtual TINAG offerings as well as sharing the project as a template to be utilized by schools and community organizers and activists. I have gathered nearly 300 ceramic objects, each made by an individual at one of these events. The objects compile an archive of the projects—all meant to be displayed as one monumental memorial to those affected by police violence in the U.S.

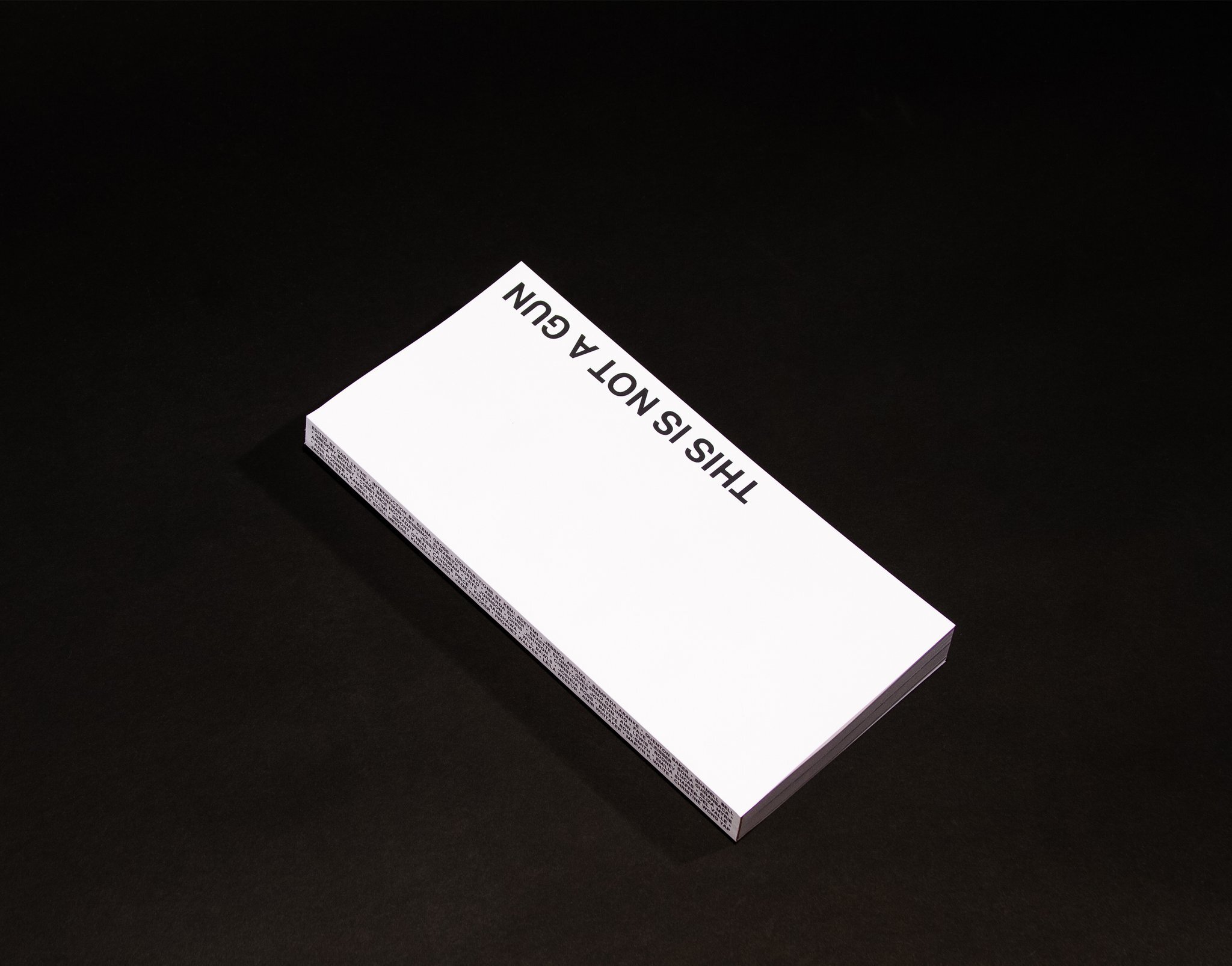

Lastly, and very proudly, this year we published a book, also titled This Is Not A Gun—which is how I think you and I were connected. The book is a collection of 40 contributions by writers, activists, artists, and healers, all writing on one of 40 unique objects mistaken as guns. It was co-published by Sming Sming Books and Candor Arts. The book was an opportunity for me to bring forward some of the many voices who have contributed to TINAG along the way, as well as to reach out to artist heroes (a theme) whose work I thought would compliment the collection. There is a vast breadth of work in this collection, but all told, I think what you come away with is a deep sense of the sheer ordinariness in these objects, that each one nevertheless carries a different and important story.

RS: What’s next for you?

CL: I am actually in the midst of planning a new work commissioned by the American Jewish University, IJC, Institute for Jewish Creativity, program here in LA. The project is titled DIG: A (w)hole to put your grief in. In it, I will be continually digging a large hole on the Simi Valley AJU Brandeis Campus, which butts up against wild mountainland. I have brought together 7 other artists who all work with grief, to make installations or time-based works, on the land, over the course of the week, from March 6 -13. I’m very excited about the short program and can’t wait to share more. We hope to create an outdoor space where people can grieve together, finally.

RS: Thank you, Cara!