Q&A: Bill Arning

By Rafael Soldi | January 9, 2020

Bill Arning is a contemporary art advisor, curator and critic based in Houston, Texas. From 2009-2018 he was the director of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. Recent commercial gallery exhibitions include Stonewall 50/50 at 1969 Gallery in New York, Texas Extravagant Drawing at Fiendish Plots, Lincoln, Nebraska, Paulina Peavy/Lacamo and They Call us Unidentified with Andrew Edlin Gallery, Dirty Words-Mark Flood/Sam Jablon at Mindy Solomon Gallery, Miami, and Extravagant Drawing ReDo at G Spot Gallery and No Trigger Warnings at Bill Arning Exhibitions at Flatlands Gallery, both in Houston.

Previously, Arning was curator at MIT’s List Visual Arts Center (2000–2009), curating shows on AA Bronson, Cerith Wyn Evans, and Kate Ericson and Mel Ziegler. From 1985 to 1996, Arning was director of White Columns in New York, where he organized groundbreaking first solo shows for artists such as John Currin, Marilyn Minter, Andres Serrano, Richard Phillips, Cady Noland, and Jim Hodges. His writing has appeared in Artforum, Apollo, Art in America, Out, Gulf Coast, and Parkett, and he has contributed to many international publications, including exhibition catalogues on Keith Haring, Christian Jankowski, and Donald Moffett. He writes a monthly column on LBBTQ art issues for OutSmart Magazine, the gay magazine covering Houston, Texas.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Bill, thank your chatting with us. Tell me about your other life before you became a curator. Did these experiences in any way influence how you approach your relationship to art and what you’re drawn to?

Bill Arning: Very much, first of all I am a native New Yorker and my parents understood that the city itself was the best teacher. I was raised during the period when the city was considered wild, dangerous and teetering on the verge of bankruptcy and it was so very exciting for a young person.

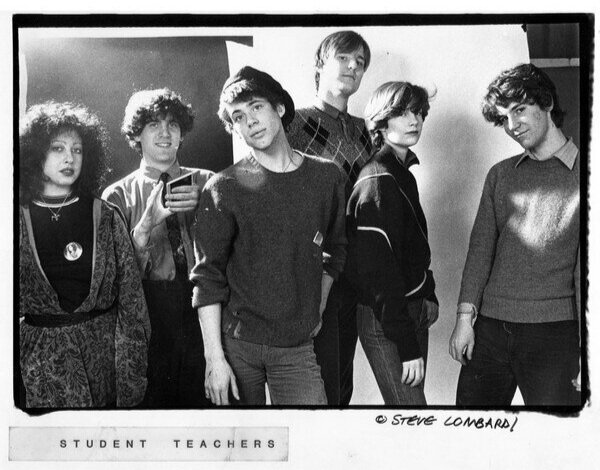

I had a band during the CBGBs period and my identification both as a curator /critic and as a gay man happened at punk clubs. Art for me was an extension of the self understanding I got from singing along to Patti Smith saying “Outside of Society is where I want to be.” I was at CBGBs or Max’s Kansas City several nights a week. I met Andy Warhol because he came to see Lance Loud’s wonderfully faggy band the Mumps. The punk folks—musicians and fans—I met there were really well read, knew artists, filmmakers, and poets. The idea of direct expression appealed to us as a generation but the pendulum between raw expression as typified by the Ramones was linked to the high artifice of Roxy Music and Bowie. When I approach artworks in any medium today I still locate them as occurring somewhere in the spectrum.

My relationship to mainstream gay culture was informed by punk’s love of rebellion too. When I see anything become too popular from beards to Lizzo my urge is to rebel. Now that I am officially a “hot muscle dad” type even the popularity of my genre of body makes me queasy, and I want to question its marketers harder as to what exactly they are fetishizing in my grey chest hair—even as I am grateful they like it.

RS: What did you take away from your time at White Columns? Any highlights?

BA: I have much to apologize to the art world for. When I started at White Columns the issue seemed to be a bottleneck in the system in which 1,000 talented artists were competing to get seen by 20 sets of eyes and what the field needed was a better mechanism for identifying the most talented makers earlier and get them the support of galleries and before the public. So I volunteered to be the talent scout, visiting studios and trying to find the best artists first. And indeed I did but what happened was the gallery scene expanded rapidly and the sheer quantity of venues became soul killing. The excuses of the last 15 years was the result and a lot of viewers and potential collectors got turned off with the boom and bust cycle of young artists hitting fame big at 25, getting crazy auction results, then disappearing as the very human response to fame coming prematurely and shutting down creatively. I do think the art world self corrected but the danger of the art world’s youth obsession still claims a few victims every year.

RS: You took a break between White Columns and the List Center at MIT. What happened during that time?

BA: I learned to write on strict deadlines… one of my best life skills. Time Out New York was just starting and Howard Halle asked me to write about exhibitions for them. As a weekly an exhibition would open and you had hours—not days—to say something meaningful about it. I had to get over my fear of being wrong in public, and I often was. Marilyn Minter told me I was never going to be a great critic because I cared about being liked too much, but I very much enjoyed bringing publics to artists having their first shows. That led to writing for ArtForum, Art in America, The Village Voice and Out Magazine. My favorite writing gig was Honcho, a leather porn mag. I was there to add content and I imagined a smart fellow who had just cum to one of the guys in the magazine—and as this was during the AIDS crisis, porn was our best friend—and reading about Pollock or Tony Feher in a post orgasmic glow.

Honcho magazine, 1980s

RS: Maricas, the exhibition you curated in Buenos Aires in 1993, pushed boundaries in more than one way. Can you share more about this, and the impact it had then and today?

BA: The art world had been radicalized in the response to AIDS and those of us who might have used the “I just happen to be gay but it doesn’t define me as an artist/curator” dodge could no longer pretend it didn’t matter. I was lucky being from a progressive family and going to school that told us gay was good; I dove in to this new freedom. When I was invited to curate a show of the great out artists of the period in Argentina it seemed incredible. I learned that AIDS had hit the Argentinian art world hard as well. The show was all over the news there and it seemed highly influential but for nearly thirty years no one asked about the show but in the last year I have gotten so many inquiries, and the delayed effect is fascinating.

RS: Work that's taboo can be hard to get past the many layers of review at institutions—do you ever manage to sneak in subversive content into the museum walls?

BA: Often, but it was easier as a curator than as director. Curators are supposed to be pushing boundaries and get forgiven a lot. As a director the board expects you to be making decisions to please all donors—even the conservative ones—so I probably took less chances in the last decade than earlier. Happy to be in the gallery world again in which all’s fair if someone buys it.

RS: Until recently you were the Director at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. What were you really proud to bring to Houston?

BA: Two shows stand out. My Marilyn Minter retrospective co-curated with Elissa Auther. When you give an artist a first major exhibition as I did with Minter it’s always the sweet joke to say, “one day I will be curating your retrospective.” Only in Minter’s case did that happen. Minter remains hard for a certain type of curator who sees her celebration of her own erotics as terrifying, but Elissa and I had a blast working on her art. The porn paintings remain incendiary three decades after their debut.

The second was Mark Flood: Gratest Hits, with the crazy spelling and insane installation. Flood is the great Houston artist who never left, always promotes this as a top art making city and he had not had a significant museum show. People seemed scared of working with him. Flood and I had really similar biographies and aesthetics so the show was a great experience for me .

RS: Tell me about the Bill Arning Gay Art Collection.

BA: I started buying art for myself right after we were were all radicalized via AIDS activism. While I was in the museum world it was always tricky in terms of ethics rules. But all my museums were non-collecting so I was able to continue adding to the collection. When I went freelance I came out as having a top quality collection of my whole generation of gay artists.

When I came out Gay was not a gendered term, it was Gay Men and Women, not Gay and Lesbian. And while I appreciate and celebrate the adoption of Queer and the long version of LGBTQIAA2, the word Gay still has power for me. By formalizing the Bill Arning Gay Art Collection and knowing how museums negotiate gifts, I hope to leverage the museum-level artists like Felix Gonzalez Torres, Jim Hodges, Wolfgang Tillmans and many others to get other more cult artists like Jerome Caja into the collection. The thought of the words Gay on museum labels 100 years after my death makes me so happy.

RS: You're now working independently and have made Houston your home. I'm really curious about "No Trigger Warnings," and the challenge it aimed to address.

BA: As a proud overtly and sexual queer, radical thinker and believer in aggressive aesthetics I feel the risks of self censoring causing curatorial squeamishness really makes my skin crawl. For my first show in Houston under Bill Arning Exhibitions I wanted to make a show that would shock many with full intentionality. I am sure in terms of my supporters some were thinking this was a mistake making a show with a giant auto fellatio painting by Scooter LeForge and harshly beautiful photos of drug addiction and death by Skylar Fein. But so many people came in and thanked me for defying the new puritans. I was thrilled to augment this with evening events like a screening of Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens’ Water Gets Us Wet: an Ecosexual Adventure and a Gay Shame Parade queer comedy night.

RS: Any upcoming projects we should keep our eye on?

BA: In April, 2020, I am presenting Roey Victoria Heifetz: Mural Drawings and Mad Scenes. She is a trans artist from Jerusalem, now living in Berlin. These are massive drawings of femme fatales that are scary and fabulous and beautifully drawn. They are nightmare images of how we see ourselves as we age as sexual beings, trans and otherwise. I saw her museum show in Jerusalem three years ago and it blew me away.