Q&A: Lisa brittan + gary van wyk

By Rafael Soldi | Published December 3, 2015

Lisa Brittan and Gary van Wyk founded Axis Gallery in 1997 as the only US gallery promoting both "traditional" and contemporary art from Southern Africa. Both programs soon broadened to cover more of Africa, better fulfilling what the name Axis was chosen to evoke: the intersection of the cultures of Africa and the West. During its first ten years, in Chelsea, Axis Gallery staged several groundbreaking, critically acclaimed exhibitions, and gave several South African artists their first exposure in New York.

Today, Axis Gallery shows contemporary art by African artists at its Williamsburg gallery and other venues. Antique African art is shown by appointment only at its New Jersey location, with emphasis on museum-quality pieces from the neglected traditions of southern and eastern Africa.

Axis Gallery's director, Lisa Brittan, and curator, Gary van Wyk, trained both as artists and art historians in South Africa during the 1980s, and were active in the anti-apartheid Resistance Art Movement. In addition, Lisa Brittan is a documentary filmmaker and Gary van Wyk, Ph.D., is a scholar of African art and an editor. They have served as guest curators, exhibition consultants, and collection appraisers, and have contributed to the collections of leading museums in the United States and internationally.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Gary and Lisa! Tell me a bit about your personal histories, your early activism in Africa and how you landed in the United States.

Lisa Brittan + Gary van Wyk: We met in the 1980s at art school, in Johannesburg, We were drawn together by our shared view of art as a socially engaged practice during the height of apartheid oppression. The conflict ramped up in 1985, when a state of emergency was declared, giving the state extreme powers. Hundreds of activists were being arrested or killed and the media were muzzled. Reporting on or Illustrating the police or military in action, or the resisters, was defined as terrorism. Newspapers responded by leaving blank areas for the banned images and text. Then the state banned those white spaces, underscoring how political representation had become and how powerful images were. We took to the streets at night, pasting composite poster murals in prominent places to present the forbidden. We would then alert the press, which published the anonymous art works before the state could remove them. A highlight of our short-lived artistic practice was when our artwork featured as the front-page photograph in South Africa’s major newspaper, standing in for real events that could not be pictured.

We were among the first students offered African art courses in our art history curriculum, and these courses revealed to us the richness of African cultures that apartheid education had always denied and denigrated. Gary, as a white male, faced conscription, which he had delayed by completing the maximum allowance of two degrees—and then extended by getting special permission to double-register for a fine art degree while completing his LLB. Finally, though, his exemptions had run out, and in 1986 we went into exile in Zimbabwe. There, Lisa founded a company designing and printing art textiles, and began working in documentary film, which has been a sustained interest in her career. Gary continued graduate studies in African art history, by correspondence, while working in television. He also sneaked back into South Africa to curate a documentary exhibition on South African mural art. Because it juxtaposed the diverse traditions of various local cultures—opposing the strategy of apartheid—it was critically received as “one of the most influential cultural events of the decade.” As a result of these activities, Gary was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship to Columbia University’s Ph.D. program in Art History, and we moved to New York in the fall of 1989. Lisa worked as a producer at the Emmy Award-winning PBS weekly TV program “South African Now,” focusing on activist cultural segments.

In 1990, we witnessed the release of Nelson Mandela on TV, dancing up and down in each other’s arms in our pokey little Columbia apartment. This political reversal enabled us to return to South Africa for Gary’s fieldwork research on the traditional mural arts of Basotho women. This became a photographic exhibition after his return to New York in 1994, and was later incorporated into his first book, African Painted Houses. Lisa made a parallel documentary film on Basotho murals, Sacred Signs / Les Signes Sacres, which was shown at the Guggenheim in New York, at Musée d'art moderne Villeneuve d'Asq, in Lille, and at Musée des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie, Paris. While in South Africa, Lisa directed “We’ve Got the Power,” a documentary on South African music and resistance that won first prize at Cannes’ MIDEM International Visual Music Awards. She also directed several music videos and TV features in Egypt (“Aida” performed at the Temple of Hatshepsut in Luxor), Kenya (Sankomota) Nigeria and Ghana (Rock down Africa) and South Africa (Lucky Dube, Johnny Clegg, Brenda Fassie, Mzwakhe Mbuli) focusing on leading African musicians and artists before returning to New York in 1995.

RS: Lets talk about the beginnings of Axis, tell me about your years in Chelsea, "Postcards from South Africa," early reviews, and the costume collection.

LB + GVW: A friend approached Gary to consult on a family-owned collection of African art that had become marooned in the United States after an untidy divorce. Gary inspected a series of broken crates in a vermin-infested warehouse, and immediately noticed important objects among the contents, including magnificent beaded pieces and full costumes dating to the peak period of beadwork production among the Xhosa, Zulu, Ndebele and other South African peoples, which were vital to save. Gary was at this time employed as an editor of African books at a New York publishing house, but Lisa took on the task of saving, sorting, and cleaning the collection. In September 1997, we rented a desk at Richard Anderson Gallery on 17th Street, and an adjacent storeroom. As Lisa processed the collection, she began to move it into cabinets in one corner of the gallery.

Our first aim was to incorporate African art from South Africa into museums, but this meant changing entrenched Western stereotypes about African art that emphasize dramatic masks and figures carved by men, usually from West and Central Africa. Rather, southern African traditions are often abstract and restrained, and beadwork, created by women, is a key medium for addressing the ancestors. Fortunately, several enlightened museum curators and fellow Africanists were also eager to expand the canon. Our early sales to the French national museum system and to the Art Institute of Chicago confirmed that we were on the right track, and enabled us first to take over more of the gallery, and later to rent the entire gallery for exhibitions.

The trade embargo against South Africa and the academic boycott had also hindered knowledge appreciation of South African arts—both “traditional” African art and contemporary art—and Axis Gallery grew rapidly to represent both aspects, since we knew so many South African artists and curators personally. The New York Times critic Holland Cotter once said that “Axis Gallery made New York history by integrating African art, old and new, into the fabric of the contemporary Chelsea gallery scene.” [May 22, 2006] Our first contemporary art show, “Postcards from South Africa,” opened 9/9/1999, showing postcard-sized works by 80 artists curated from responses to an open call, opened just before the first museum show in New York of South African artists, and it gave many South African artists—such as Senzeni Marasela and Jo Ractliffe—their first exposure in the United States.

During our first decade, we were pioneering new territory and often serving as cultural ambassadors—doing precisely what we chose the name “AXIS” to signify, serving as an axis mundi that linked the diverse worlds of Africa and New York. But the art world moves fast, and before long several other galleries were representing South African artists, curators and collectors were visiting South Africa frequently, and we then expanded our focus to include artists from other countries that still had less exposure at the time, including Nigeria, DRC, and Cameroon. At some point in the future, if we do our job well, the “African” specialization will become redundant.

RS: One of the most impressive things about your careers has been your undying commitment to art of the African continent, championing a very specific genre. At the same time you have remained very nimble, redirecting your focus towards scholarship and art from underexposed regions. How important is it to you to stay ahead of the curve and how have you done that over the years? What are some of the types of art and geographical regions that you have explored throughout your career?

LB + GVW: We like to present new perspectives and to produce change, but being ahead of the curve sometimes means that your ideas are ahead of their time. Our first foray into art dealing was in 1990, when Gary conceived the idea of assembling an African Art Heritage Collection of southern African works to repatriate to South Africa—because in the 1990s local African art was virtually absent from South African art museums. He collaborated with the late Norman Hurst, a respected Boston dealer, to buy antique southern African art on the international market, and hoped that major South African corporations might sponsor the repatriation of the art because they recognized the need to affirm African culture, and make reparations for their complicity in the apartheid system. Frustratingly, corporate sponsors did not understand the opportunity, and prices for this material were escalating rapidly as the market caught onto African art from the south. Fortunately, the director of the South African National Gallery, Marilyn Martin, and the German consulate backed the goal of repatriating and inserting local African art into the South African National Gallery, and the German government presented the core of the collection as a gift from the German people to South Africans in honor of South Africa having achieved democracy in 1994. This experience taught us crucial strategies about the market, and dealing with sponsors and museums, as we later worked to expand the canon of African art through Axis Gallery. As African art collections expanded to include South Africa, we moved on to promote other neglected regions.

Axis curated many exhibitions that were “firsts” for the United States. We introduced several contemporary artists and photographers who have become established and entered museum collections. We exhibited William Kentridge’s prints before he was widely known. Our personal interest in photography prompted us to exhibit many documentary photographers who were later integrated into museum shows in New York, particularly in Okwui Enwezor’s “The Short Century” at P.S.1 and his “Apartheid” show at ICP. To be ahead of the curve in New York, one must stand out in dialog with the city’s excellent museums, flesh out what they exhibit, present a counterpoint. Critics have frequently mentioned Axis’s success in this regard, which stems, we believe, from our professional grounding as both artists and as art historians, which lies behind what we curate.

RS: Likewise, AXIS gallery has undergone a series of metamorphoses. Walk me through some of the iterations of the gallery both conceptually and physically, where it is now, and the different roles it was played throughout the years. How important is it for art spaces to be flexible and adaptable as the mission evolves?

LB + GVW: We progressed rapidly from a rented desk to the idea of exhibiting and selling art, and before long we had taken over the gallery and instituted a regular program of exhibitions, showing both “traditional” and contemporary art from Africa. After ten years, our lease fell due, and we fell victim to the greedy landlord syndrome. Facing tripled rent, we were about to lease and subdivide a large new space when the 2008 crash hit. While we sat out the trough of the 2008 Depression, we used our home in New Jersey as a showroom for showing African art to curators and clients. This worked perfectly for African art, but for contemporary artists to have exhibitions we felt we needed a gallery, so we moved Axis Gallery to Dobbin Street, in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, and also focused on placing our artists in museum exhibitions and other venues. An art foundation that we direct with two colleagues, called AlmaOnDobbin, operates from there today. Axis has become more peripatetic; for example, showing at art fairs in New York, London, Miami, and Budapest in 2015 in order to take advantage of changed patterns of gaining exposure for one’s contemporary artists and gallery program. We have also rented gallery spaces in Manhattan and in downtown Newark to present solo exhibitions, when needed, and this strategy has also worked for us. Cutting down on the administration of a fixed space with a nine- or ten-month exhibition schedule has enabled us to do demanding projects with AlmaOnDobbin and other institutions.

RS: Lets talk about education. You've expressed to me that educating the public is a big part of what you do, and often times this means working with museums and institutions to accurately represent African art. What is the current state of African art in American institutions, and what are some of the things you have done to help educate the public?

LB + GVW: The distinction between “traditional” and contemporary African art creates two parts to this question. Several contemporary artists of African origin have gained substantial critical and market recognition for their work—such as El Anatsui, Julie Mehretu, William Kentridge, Yinka Shonibare—but the admission of a few artists into the canon cannot serve as tokenism that obviates the ongoing, serious assessment of other African artists. Unfortunately, ingrained prejudices against Africa persist within the artworld, because the education of many, if not most, art professionals in the West generally lacked, and still lack, serious consideration of African art—traditional or contemporary. They have a black hole in their education. The corrective, performed by African artists, curators, art historians, as well as by Africanists from elsewhere, is already well underway. The impact of Okwui Enwezor’s curatorial work—enabled by those who have had the foresight to appoint and empower him—is outstanding in this regard. He has brought to bear a social and political perspective at Documenta and the 2015 Venice Biennale that we as Africans and as curators find ourselves in harmony with, but that can seem discordant with more superficial tendencies in the artworld—especially the rampant commercialism driven by an “investment” mentality. On the other hand, it sometimes falls to the curators of African art in institutions to take responsibility also for contemporary art from Africa, and this can also lead to misunderstandings and misfires, because the professional skills and frameworks of contemporary art are distinct from ethnographic frameworks.

Regarding “traditional” African art, many museums in the United States—but not all—have integrated South Africa into their displays, with more or less enthusiasm and conviction. Sometimes this extends to media other than wooden sculpture, such as beadwork or ceramics or basketry, and this we find deeply satisfying. However, vast swathes of north Africa and east Africa often still are omitted. One of the last exhibitions at Axis in Chelsea was “Atlas Warp: Talismanic Rugs of Moroccan Nomads,” which profiled another overlooked form of African art produced by women—and one that played a vital role within Western modernism. As long as museums apply Western categories—“a rug is applied arts” or “decorative arts” or “it’s a textile”—it is difficult to re-contextualize the rug as symbolic and talismanic African art, but that is what we did at Axis, and hung the rugs on the walls to underscore the relationship to such Western forms as color-field painting.

Shangaa: Art of Tanzania was an exhibition project that Gary produced for QCC Art Gallery, CUNY, and the Portland Museum of Art, Maine. It aimed to demolish the false perception that east Africa lacked figurative art by presenting an array of sculptures, many borrowed from little-known collections in museums formerly behind the Iron Curtain. The accompanying volume of scholarly essays was the first comprehensive book in English on the art of Tanzania, which includes more than 120 ethnic groups. The project, which also grew out of our interest in neglected regions, took several years to produce, and involved undertaking fieldwork research in different regions of Tanzania. The project was widely acclaimed by H-AfrArts review, African Studies Review, New York Times, Wall Street _ Journal, The Boston Globe, The East African, New York Times Critic's pick. It poses a compelling case for the inclusion of east African art into the canon.

RS: Even within the context of African art you have worked to expand the reach of what gets recognition; one of your efforts has been to highlight more work by women artists. Expand on that.

LB + GVW: The West’s masters of Modern Art, Picasso et al, who mainly embraced the dramatic masks and figures carved by other men in Francophone West Africa, skewed the West’s view of African art. It is rare to find the work of women artists in traditional African displays, and this should raise questions. By showing beadwork, fine ceramics, basketry, and such textiles as the Atlas rugs we suggested that African aesthetic experience—including senses of sacredness—often were located in these media and in these types of women’s work that were being excluded for no good reason—but rather through the reinforcement of stereotypes that deserved to be questioned. Because of their sacred functions, a pot or a beadwork costume might be of equal or greater aesthetic importance than a figurative carving in the original African setting, and therefore could and should stand among the figures in the museum vitrine. In other words, this is not just a pot, this is not merely beadwork, ceci n’est pas une pipe.

Going back to our earlier work on Basotho women’s mural paintings, these were sacred forms that directly addressed the ancestors—yet it is rare to find women’s mural paintings taken seriously in museum displays, because entrenched Western stereotypes and frameworks for African art preclude this. African rock art—the most primordial sacred art—is also usually excluded although one could argue it is the very foundation of human art.

In the contemporary art field, we have presented numerous women artists. For several, we provided their New York solo debuts or first placed them in major American museum collections—including Helen Sebidi, Berni Searle, Ledelle Moe, Jo Ractliffe, Sue Williamson, Senzeni Marasella, and Jo Smail.

RS: Talk to me about your work with Alma on Dobbin and the projects you've been working on.

LB + GVW: Alma is an art foundation that promotes links between the arts of America, Central and Eastern Europe, and Africa. We are finishing a busy period. In 2015, in New York, we produced “József Jakovits: Surrealist, Primitivist, Kabalist,” the first solo show in the US for this important Hungarian modernist. Gary’s accompanying monograph on the artist is the first in English. Alma is currently presenting “Sculptors ’56” at the Balassi Institute / Hungarian Cultural Center, to commemorate the Hungarian Uprising. This show will travel to Berlin in 2016. Right now we are developing programming to accompany a major exhibition on Moholy Nagy at the Guggenheim during 2016. Alma has co-produced an exact facsimile of telehor 1-2, a rare edition of a short-lived magazine, that was a virtual manifesto of Maholy Nagy’s approaches to art, film, design, language, and performance. The facsimile is accompanied by an original scholarly commentary, and we plan to launch these during the Maholy Nagy focus. Alma also co-published a major book on Andor Weininger, another Hungarian at the Bauhaus who participated in the little-known Bauhaus band, and recorded some of its music. We plan to present a reimagining of his Bauhaus recordings.

On the African side, Alma is co-sponsoring The Tree Walker, an ambitious project by Berlin-based artist Christoph Both-Asmus, to walk across the forest canopy on the border between Gabon and Congo Republic. Alma is also developing an exhibition for a group of young artists who have mixed African-Hungarian heritage, to be staged in Budapest in October, 2016. One of them, David Gutema, posed as a Syrian or African refugee and surreptitiously filmed the treatment he received when asking taxi drivers what they would charge to drive him to Hungary’s borders. We will be premiering Gutema’s work in Budapest at 2B Galéria, our sister institution in Hungary, this December.

We are again traveling Alma’s long-running and ever-expanding exhibition project called Waldsee—to South Africa and Poland. “Waldsee,” which literally means Forest Lake in German, calls on artists to imagine that they have been allowed to mail a postcard-sized work from a concentration camp—in fact, the Nazis permitted some censored mail, postmarked with this false location, the misleadingly named “Waldsee.”

RS: Tell me about some of the artists you're excited about right now and any upcoming projects.

LB + GVW: It’s been an exciting year for our artists. At the Venice Biennale, Lisa enjoyed meeting with Sue Williamson and with Sammy Baloji who featured in the Belgian pavilion, and on All the World’s Futures, curated by the director, Okwui Enwezor. Baloji is currently featured in So-Called Utopias, at the Logan Center for the Arts, Chicago, and in Earth Matters: Land as Material and Metaphor in the Arts of Africa, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Maine. He created a new installation for La vie modern, curated by Ralph Rugoff, currently at the Lyon Biennale, and has works in Beauté Congo 1926-2015 Congo Kitoko at Foundation Cartier and at Après Eden at Maison Rouge, Paris.

Sue Williamson participated in the collateral project Border Line: Rights of Passage, an art publication assembled at the Venice Biennale. Williamson currently has a solo show, Other Voices Other Cities, at SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, which will travel to SCAD, Atlanta. She will launch her new monograph, Sue Williamson: Life and Work, later this year and sampling from her series A Few South Africans will be on view in the Collections Gallery at Tate Modern, London, this November..

Bright Ugochukwu Eke was featured in Africa-Africans at Museu Afro Brasil, São Paolo, Brazil, earlier this year and Axis profiled two new works at 1:54 New York and London.

Theo Eshetu is currently featured in Tu dois changer ta vie! the 4th edition of Lille3000, Lille, France, and in Streamlines: Oceans Global Trade and Migration, Deichtor Hallen, Hamburg, Germany and Après Eden: The Walther Collection, at Maison Rouge, Paris. Recently he showed in A story within a story, 8th Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art – GIBCA, Sweden, STADT/BILD Xenopolis, at the KunstHalle by Deutsche Bank, Berlin, and Nero Su Bianco, at the American Academy in Rome. This exhibition also featured the work of Jebila Okongwu who joined the Axis stable in August this year and who we featured in a solo exhibition at 1:54 London in October.

Graeme Williams’s exhibition of his prize-winning series, "A City Refracted" has been traveling to art museums throughout South Africa, and also gained exposure in Europe and was featured in the World Atlas of Street Photography. His work is also featured in Earth Matters: Land as Material and Metaphor in the Arts of Africa, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Maine, through March 2016.

Hervé Youmbi recently represented Cameroon at Lumières D’Afriques, at Théâtre National de Challot, Paris. He is currently in Senegal at an artist-in-residence program, on Gorée island and Saint Louis, researching for the exhibition Emancipation Stories / Mémoires libérées, which will travel to Cameroon, Senegal, Haiti, Antigua & Barbuda, and France, starting in May 2016. We premiered in London a major conceptual installation that Youmbi has been working on for several years, which concerns the tension between “traditional” and “contemporary” African art in Western minds—a very pertinent project for Axis’s mission. We are delighted it has found a home in a prominent museum.

RS: What's next for Axis? Where can we find you?

Next is CONTEXT Art Miami. We will be showing Sammy Baloji’s new diptych, “Gorilla Territory,” which we premiered at 1:54 during London Frieze week. Concurrently with the weekend of Art Miami CONTEXT, Lisa will travel from Dec. 5-6 to the Rolex Arts Weekend taking place in Mexico City, where Sammy Baloji will present a site-specific photographic installation in the lobby of Teatro Julio Castillo, and will participate in a dialogue with Olafur Eliasson, as the culmination of their one-year partnership through the Rolex Mentor & Protégé Award.

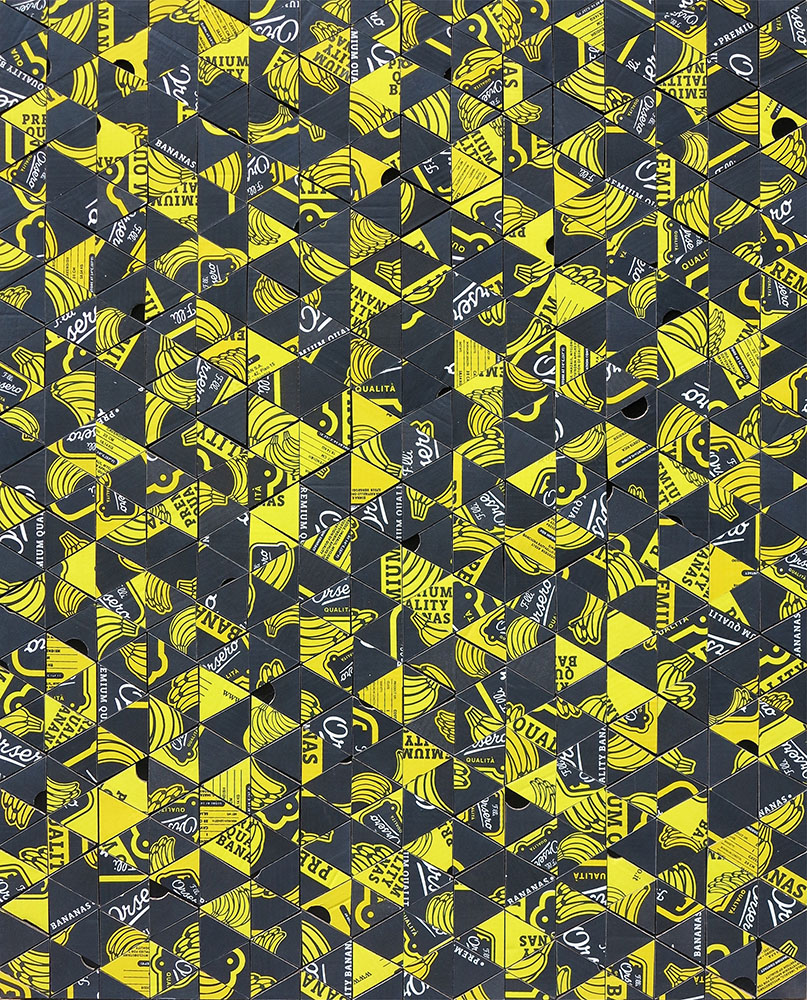

We will also show Theo Eshetu’s “Anima Mundi / Soul of the Universe,” a stunning immersive experience of film and sound projected through an optical device that multiplies and replicates infinitely until it takes the form of a sphere. We will exhibit a 9’ x 9’ section of Bright Eke’s “Ripples and Storm,” made from upcycled plastic bottles that radiate like an energy source. Jebila Okongwu’s works made from banana boxes slyly reference patterns of exploitative labor and trade, as well as sexuality. We will also show a selction of images from Graeme Williams’s photographic series, “A City Refracted,” for which he was hailed as one of a dozen photographers that change the way we see the world.

In the Spring of 2016, during Frieze week, Axis will show again at 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, New York, staged at the magnificent Pioneer Works in Red Hook. Axis will partner in exhibiting the work of Bright Ugochukwu Eke with UFO in Los Angeles in Green Piece, in June 2016.

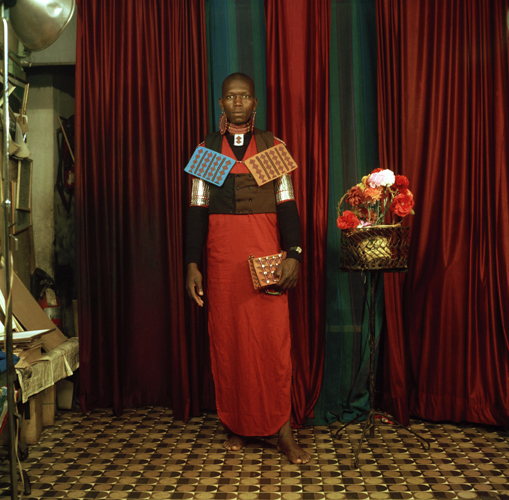

© Bobson Sukhdeo Mohanlall, Untitled #35, 1960-1970

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Bobson Sukhdeo Mohanllal, Untitled #33, 1960-1970

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Theo Eshetu, Anima Mundi / Soul of the Universe, 2014

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Theo Eshetu, Anima Mundi / Soul of the Universe, 2014

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Sammy Baloji, Gorilla territory: Hunting & Collecting, 2015

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Sammy Baloji, Gorilla territory: Hunting & Collecting (detail), 2015

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Graeme Williams, from A City Refracted / Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Graeme Williams, from A City Refracted / Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Jebila Okongwu, Divination Painting no.1, 2014

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Jebila Okongwu, History Painting (after Géricault), 2011

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Jebila Okongwu, Ankwa, 2010 / Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Sue Williamson, There’s something I must tell you, 2013

(installation view) / Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Sue Williamson, Other Voices Other Cities, 2009 - / Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Hervé Youmbi, Bamileke-Dogon Ku'ngang Mask, 2014

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Christoph Both-Asmus, from The Tree Walker / Courtesy Alma on Dobin

© Christoph Both-Asmus, from The Tree Walker / Courtesy Alma on Dobin

© Bright Ugochukwu Eke, Ripples and Storm i (Detail), 2011

Courtesy Axis Gallery

© Bright Ugochukwu Eke, Ripples and Storm ii, 2011

Courtesy Axis Gallery