Q&A: Andy Slemenda

By Katherine Sperber, guest contributor | March 30, 2017

Andy Šlemenda is an interdisciplinary artist from Appalachian Pennsylvania, currently living and working in New York City. He received his M.F.A. at New York University Steinhardt and his work has been exhibited in New York City, Paris, Istanbul, Berlin and Toronto. His latest site-specific installation, Blood of the Air, in Galveston, Texas, draws inspiration from Sufism and Terence McKenna, in the hopes of remapping consciousness. His work energetically reconfigures the space it inhabits through his juxtapositions of ready-made and organic materials mixed with his provocative interpretations of esotericism and folklore, transporting his audience into an otherworldly environment.

Katherine Sperber is a consultant and writer currently living and working in San Francisco. After studying Art History and French literature at George Washington University and the Sorbonne, she began coursework in Visual Theory at New York University with a master's thesis on the invention of photographic self-portraiture. For four years she worked at an international auction house in collection management, working with the property of George Cukor, the Doheny family and Lauren Bacall, amongst others. She recently cofounded Spleen, a literary collective, with poet Jessica Lauffer.

Katherine Sperber: How did you discover art and when did you first identify as an artist?

AS: The first time I recognized something as an art object was, weirdly enough, an out of body experience that happened in church. My mom and grandma would always let me doodle during the sermon to keep me occupied. I remember once being at church on Easter, my favorite holiday, and they had erected a replica of Christ's tomb at the altar. My grandma told me that the stone tomb was an oil painting which seemed so magical. That was the first moment I had heard someone refer to an art object in this canonical way. All of my earliest art discoveries came through my family. My great grandmother was a seamstress, ceramicist and painter. She would paint on saw blades because my great grandfather owned a sawmill and she also made ceramic toads, gnomes and the like. On the other side of my family, my grandfather and his brother were commercial artists and my grandfather would draw pinups and seasonal decor, Halloween ghosts and stuff for people’s front lawns.

KS: Do you have any of their art?

AS: My grandfather and I would often draw together. We devised a lot of different characters. One character in particular was this creature named, Orb. It was orb shaped with a large pointed grin, like a jack-o-lantern, standing on robotic legs, and topped off with a fiery stained-glass headdress housing a single eyeball. Throughout my practice, I've returned to that visual language my grandfather and I came up with. I also have a porcelain red and black mushroom made by my great grandmother.

KS: Clearly where you grew up and the family you grew up in had a big impact on you as an artist. I feel like not a lot of artists come from where you come from; this very rural, formerly industrial, conservative and impoverished landscape, the former rust belt of America. How has this landscape impacted the art you've made?

AS: I certainly feel that my work, on a material level, tries to engage with nature and the folk culture I was immersed in growing up in Western Pennsylvania. Strangely enough, growing up queer in that world created unique possibilities in establishing my gender and sexual identity. When I started to play with gender boundaries, there was no language for what I was doing, so it was tolerated, as long as it did not cross a certain gender-definable line. It fostered my development toward a queer, gender-fluid path. My life and work have always circulated around those experiences of gender performance, the body and nature that were so interconnected during my youth in Pennsylvania.

My family practices hunting, which is very common where we're from in rural Pennsylvania, and they live off what they kill in order to survive the harsh winter months. I grew up with my father skinning and butchering deer carcasses, seeing the anatomy of these animals and the craft of preparing the meat, made a big impact on me. I've been talking to my dad on the phone recently, trying to convince him to make rawhide for me. I like rawhide because it's not tanned at all, it is essentially just stretched out hardened skin, which I find really beautiful in its simplicity. The artwork that my family made certainly contained that folk, craft-based language and my own journey as an artist has been rewriting this idea of craft or “outsider” art.

KS: I believe the first artwork of yours that I saw was your reimagining of The Raft of the Medusa, which is one of my all time favorite paintings. Considering the impact other writers and artists have had on my own work, I wanted to ask, if there is a particular artist or piece of art than has been meaningful in your formation as an artist?

AS: That's a challenging question, but I think in terms of lineage for me, Joseph Beuys is an artist that definitely impacted my practice. I’m attracted to guru figures embodied by Beuys, Paul Thek, James Lee Byars, Genesis P-Orridge and others. There's a spiritual quest aspect to their work that's embedded within the materiality of the work itself. My work as an artist is very invested in concepts and my challenge has always been to situate those concepts in materials and processes. Beuys imbued his work with a kind of mythos and that was powerful to come into contact with early on.

I will also add that one of the first artists I ever loved was Frida Khalo. I always had an attraction to the rejects of Surrealism, many of which were women. I recommend the book Angels in Anarchy which talks about Dorothea Tanning and Leonora Carrington, among others. I was drawn to these female artists as they were coming into these surreal subconscious mental planes through the marginalized experience of being a woman, which was relatable to my own struggle with identity. They were the true visionaries who really fueled the fire for their male counterparts and remain under appreciated still today.

KS: I can really see the correlation between you and Frida Khalo as so much of her work is about her body and the limitations of the body, as expressed through a material practice very rooted in Mexican folk art. Whether you're drawing fantastical figures with otherworldly bodies or using skins, there is an overarching theme in your work about the body and corporeality. Why is this an important theme for you? How do you conceive of the physical body in your artwork?

AS: I love the word "corporeality", just taking the word apart to see “corpus”, which is Latin for “body” and "reality" next to it; there is so much to unpack. My practice emerged from my training in drawing and printmaking. Over time, I became more interested in performance as it felt like such a departure from my drawing and printmaking background, and it lends itself so well to expressing the body. There was a lot of pressure on me around this time to be delineated into something, some rigid idea of the self. In that struggle, I began to see the body as a structure to escape. Eventually, the props and sets of those performances started to dominate my work, leading me to installation, where the body has grown more atmospheric.

Corporeality in my work is about the body's structure that contains and restrains our gnosis or spirit. These ideas led me down a more metaphysical path, further influenced by myths and literature about the body and transcendence. In Norse mythology, there's that awesome origin story when the giant, Ymir, is overthrown by Odin, and his corpse becomes the Earth that all humanity lives on. There are so many corollaries between our bodies and the universe; our bodies are really mirrors of a greater structure, they are a microcosm and macrocosm. There is something freeing in viewing the body this way. Lately, I've been trying to tap into these concepts within my practice, on a larger-scale with my cosmic installations or in these marbled and decoupaged works on paper. In these works, I marbleize tissue paper in water and quickly adhere the wet tissue onto the surface of large free-form sheets of watercolor paper. The result of the process looks like cellular division inside the body and at the same time feels like the expanding universe. Maybe these mirrored processes indicate that our bodies and the universe are the same system, they're not as separate as greater society would have us think.

KS: So switching gears, tell me a bit more about your recent work, especially your latest installation Blood of the Air, which you put together in Galveston Texas as part of the Galveston Artist Residency.

AS: I was invited to do that project in a sizable space, you know the saying "everything's bigger in Texas" *laughs*. Well that large space did give me a certain amount of freedom I just don't typically have as a New York artist. I was really inspired by the city of Galveston as it's such a strange place with a fascinating history. It was once a prosperous port city that was hit with one of the worst hurricanes of the century, with an architecture somewhere between Key West and New Orleans. I was also attracted to the location as I've been fascinated with these paradisiacal island sites.

The work that I ended up making came together through a variety of different concepts, one being Sufism. At the time, I was reading a book by Idries Shah about Sufism, and he interprets Sufism not just as a mystical form of Islam, but as a secret society similar to Freemasonry. One of their foundational narratives is about an island. It describes this society that lead essentially perfect lives, surrounded by culture and beauty. Until one day, their ruler foresees that their kingdom will come to an end. Consequently, he moves all of the inhabitants to an island not nearly as idyllic in order to save them. To help the inhabitants adjust, he erases their memories of the original paradise. However, a few people retain visions of the original kingdom; they hold a secret knowledge and generations down the line they begin to train in secret as swimmers and later as shipbuilders to go back to the original kingdom. The rest of their society persecutes these shipbuilders for their beliefs. Idries Shah sums up this allegory by saying that the Sufi are the shipbuilders of our society who are seeking paradise with their secret knowledge, beyond the confines of this island, which represents our limited view of reality. Essentially, we are confined to an island of our own self awareness, incapable of accessing the vast oceans of self discovery.

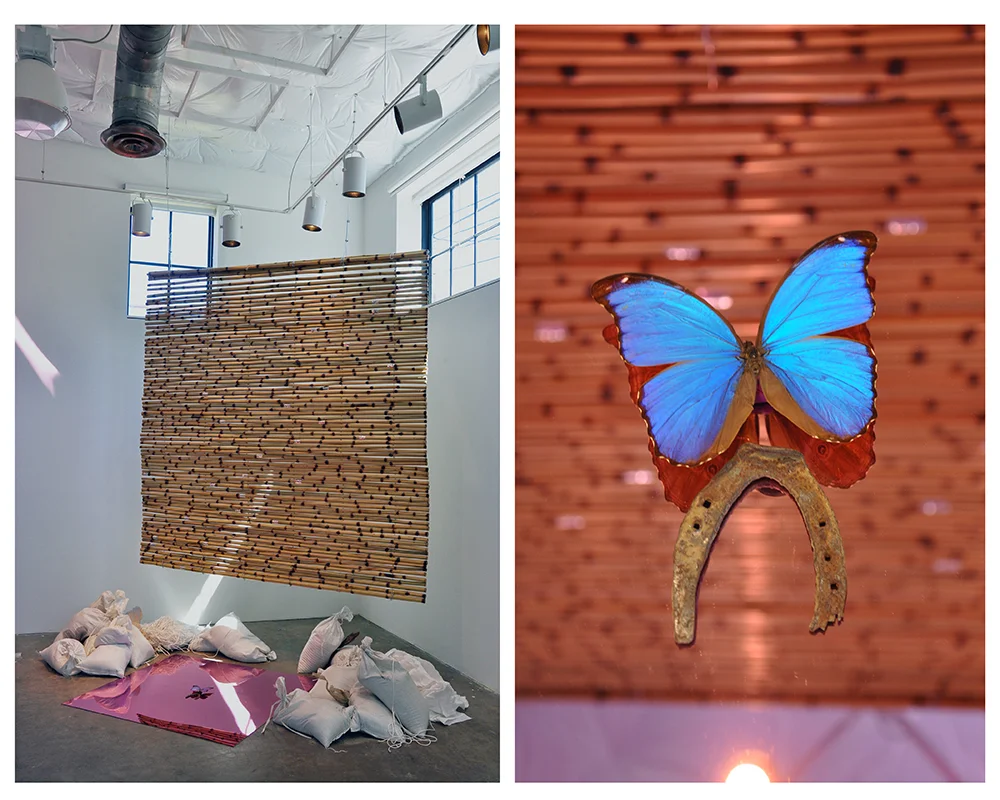

That narrative opened up a lot of things for me, especially in a visual sense. I knew I wanted to create a sculpture that could levitate, like a sculpture out to sea, a kind of planetary island. I found a vinyl weather balloon, that could hold over 350 pounds of helium, inflating to 8 ½ feet in circumference and that became the central character within the work, which I transformed with oil stick and other materials. From there, thinking about paradise and exoticised materials, I got some bamboo fencing that we hung from the ceiling in the corner of the space. I placed a pink acrylic mirror at the base of the bamboo as a kind of corporeal reflecting pool. At the time, I was also listening to the audiobook of Terence McKenna's True Hallucinations where he goes into the Amazon rainforest to seek out psychotropic plants and fungi to expand consciousness. There's this beautiful part where he sees a bunch of blue morpho butterflies. They're naturally reflective and iridescent blue in a way that seems almost unreal. As McKenna describes them, he begins to recite a passage from Nabakov's Pale Fire. When I heard this portion of the audio, I knew I had to have one of those butterflies on the pink mirror. I'm fascinated by manufactured materials having a kind of visual relationship with natural materials. When I added the morpho to the mirror, it created these multi-colored light rays that would refract off the mirror and shoot around the gallery space depending on the sun’s position throughout the day. That light effect was furthered by flickering LED lights placed on the floor, like synapses firing in the human brain.

KS: You mention the impact of being in a new environment and how that shaped your work in Galveston. I know it played a similar role as you were creating your project in Istanbul for the Story of Hayy. Do you see travel as an essential aspect of your work? I ask that as I've spoken to New York based artists who feel that they barely interact with the environment around them. I wonder what your thoughts are on that, and generally, how does your environment play into the art you create?

AS: I think it’s hugely influential especially for the kind of work I do; site can really shape the work I end up making. Personally, I don't like the traditional white cube, because I think it's a kind of denial of the outside world. It's a forced purification of space, that's just very against my beliefs as an artist. I like my spaces to be filled with vocabulary and presence to give my works complexity. I think it's also important when going to a new place and meeting people there that you should try to see the world through their perspective. Otherwise, it feels like you are forcing your views onto people without any cultural empathy or context.

During the 13th Istanbul Biennial, I did this project for the Story of Hayy called, The One Thousand Year Old Rock and Roll Band, that was conceived around Timothy Leary's trip to Tangier to meet Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs and they go to see the Masters of Joujouka, who are Sufi trance musicians. At the time, the pilgrimage to the Joujouka was undertaken by a lot of eccentric Westerners seeking an experience beyond their own culture. With that in mind, I transformed the exhibition space with these calligraphic murals. The exhibition space was this little shack on top of a building in Istanbul’s Tophane district, right next to a tiny mosque, that blared the call for prayer into my room every sunrise. The project was created by the German artist collective, Nüans Nüans. I met this talented, interdisciplinary designer from the Turkish side of Cyprus and he recommended this text by Richard Bach, Illusions of the Reluctant Messiah. He ended up performing a Turkish translation of that text for my show. I liked bringing in that element, a perspective that was more familiar than my own; he knew the language and certain customs, but was still an outsider, still removed in certain ways.

I can see why other New York artists would say that they're not making work directly about New York. I see myself, and artists in general, as sponges; I couldn't not absorb something for my work, even if I wanted to. I work at home which makes more sense for me right now because my work is so spatial that our whole apartment has just turned into this experimental space. When I have a studio, the work just spreads over the tables and walls like contagion.

KS: I feel that so much artwork is being made for easy visual digestion, partially because it's all being promoted through visual social media streams like Instagram, which ends up condensing artwork. Do you consider your audience or accessibility when you make art?

AS: I definitely think of my work as an experience. I am creating new environments in spaces, so it's unavoidable, you have to consider how bodies will be situated within those environments. I don't really think about some kind of specific message coming through. I don't expect or need for someone to look at what I've made, and see exactly what I was thinking. In my mind, really successful works of art hold a plethora of discoveries to be had. With digital photography and social media, there is a concern now that artists are creating work that is meant to be photographed instead of experienced and are factoring those dynamics into the work they create. I'm fearful of that mindset as it's destined to create a kind of feedback loop, where there isn’t even a need to physically engage with work any longer on any level. Personally, it is such a production to document my own work and it requires a great deal of direction for the photographs to make sense as a record of that specific space and experience. I hope that the visual and cultural references in my work impact my audiences on a subconscious level, engaging people in ways that are too abstract to articulate. Forms and images are to a degree objective and yet wildly subjective at the same time. That abstract, subjective meaning you take from art is the power of visual language.

I am starting to develop my works more theatrically, which seems like the next progression for me. I would like to experiment with incorporating performers into my installations in a way that would jog audiences’ experiential drive, so they're not passively digesting the work. Call it aggressive, but now more than ever, we need work that wakes people up.

All works © Andrew Šlemenda