Q&A: Andre Bradley

By Zora J Murff | Published on May 18th, 2017

Andre Bradley (b. 1987) lives and works in Philadelphia, PA. Bradley is a graduate of Hampshire College where he was selected in 2008 as a James Baldwin Scholar and in 2012, was a recipient of the first annual Elaine Mayes Award for Photography. Bradley received a Master’s of Fine Art from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2015 was selected as a president’s scholar and was recipient of the T.C. Colley Award for Photographic Excellence. Bradley has been a fellow at Image Text Ithaca, Hampshire College’s Creative Media Institute, the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center and has work in the permanent collection of the RISD Museum of Art. Bradley’s book Dark Archives has been shortlisted for the 2016 Photo-Text Book Award at Les Recontres De La Photographie, and the 2016 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation First PhotoBook Award.

Zora J Murff: Hi Andre, thank you for taking the time to complete this interview. I came across your work through one of your fellow RISD alum, and fell in love with it the first time I saw it. Let’s start by getting to know a bit about you.

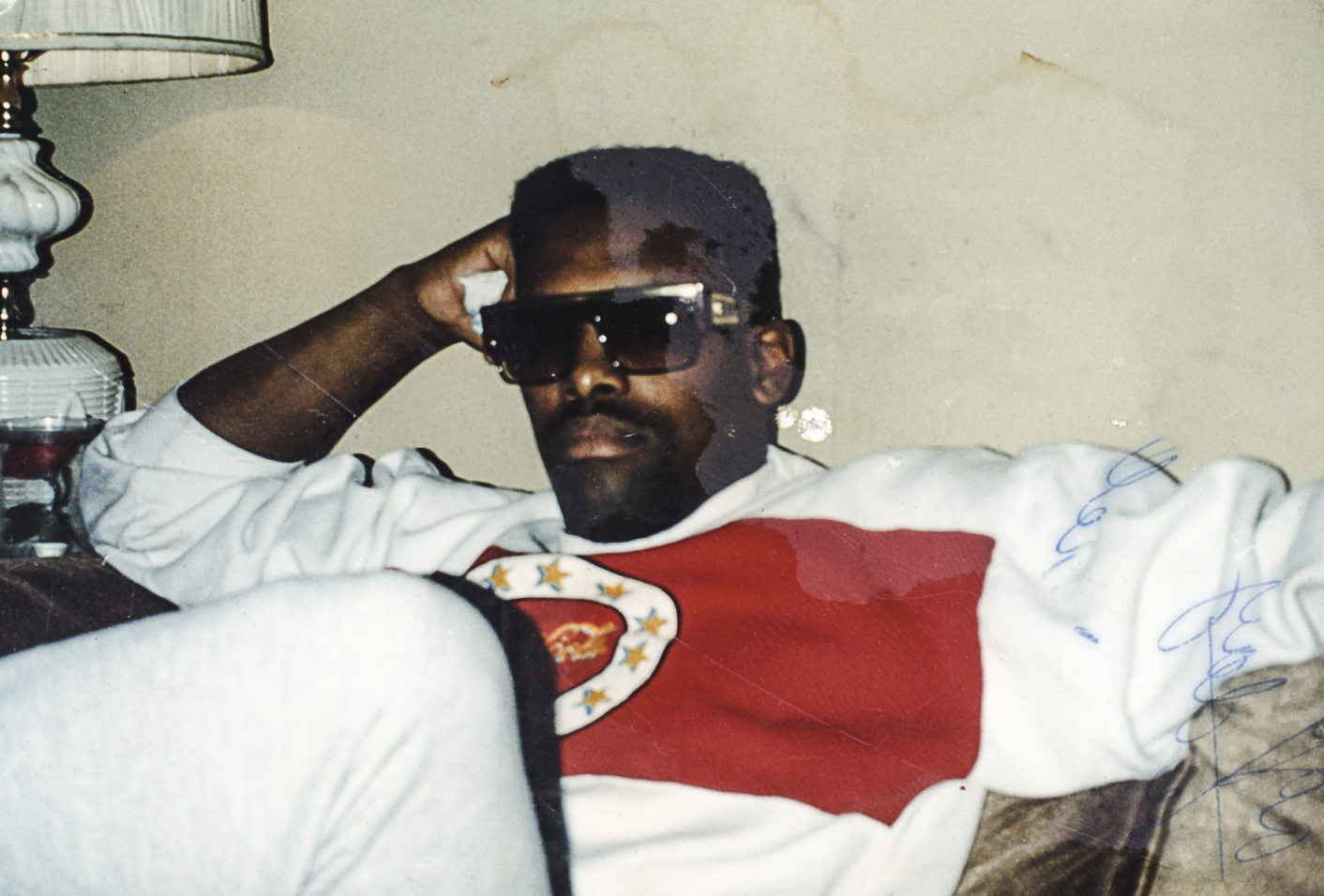

AB: My career in art has been directly influenced by my black boyhood, dropping out of high school, and, art professors in college and graduate school. I never felt good enough being a black boy, not feeling good depressed me for years and I dropped out of school, when I got to college/graduate school I desperately needed to make sense and meaning of these things, my professors helped me (and struggled with me) through this process. I was born an artist, I became conscious to this fact later in life. The biggest influence on my choice to be an artist is the idea of family.

ZJM: It seems as if the universe keeps bringing me back to your work through acquaintances. Last summer I was working on a project in Philadelphia, and one of the producers I was working with had just picked up a copy of your book Dark Archives and shared it with me on our drive from New York to Philly. After looking at the book, I checked out your website again, and the statement there reads, “Bradley powerfully combines image and text in this deeply moving meditation on narrative agency, on the family as archive, on being a young black man, and on being Andre Bradley.” The words, “on being Andre Bradley,” have always stuck with me. Your work seems to be immersed in personal politics, but I feel that it relates broadly. Why did you decide to focus on the personal?

AB: I am a private person, and I used to fear being judged for the ways I’ve reacted to events in my life. There’s always an object near an event, an individual, a family, or a photograph. The personal for me, getting vulnerable expressing my fears, shortcomings, and traumas creates a space for empathic provocation, publicly. I want my art to operate in the world in a way that incites, pressures, and provides a generous space for anyone to understand Andre Bradley’s experience as a black man in America from birth to around 27 years of age in the 21st century. There’s a copy of Dark Archives in the Denison Library’s Rare Book Collection at Scripps College. I was there and saw hand painted Ethiopian gospels from the 16th century. Imagine the individual learning something from Dark Archives five centuries from now. If it happens to be a young black man what would he think about the past as it related to his present? Isn’t there a saying about how “you become your name”? Everyone one has a name, but I see that “on being Andre Bradley” pointing to a need I have, constantly, to focus on my own individual becoming. What happens when your becoming (great, healthy, cared for etc) is hindering by politics? During this interview, I may ask more questions than I will give good answers, but I don’t expect responses.

ZJM: Do you find agency in yourself through your making, and how do you feel this translates to others?

AB: I have not always found agency in myself through making, there have been times in my life where I have intentionally made things difficult for others. I did not truly find agency in myself through making art until I found out why I had a desire, wish, want, yearning, craving and longing to be make art in the first place. With this knowledge of self, woven through the collaboration and creation of Dark Archives. Now in it’s completion I witness it produce a result in people who are then hexed into the audience of my work generally. The result I’m looking for…I’m a communicator. “Understanding is what I need.” (1)

I believe that through understanding the experience of a single individual and it moves you to tears, or anger, if empathy happens for me that’s the translation. Someone may begin to care attentively, deliberately, intentionally even about others who have also gone through similar experiences. I find agency through communicating and relating to others. I find agency in exposing where I have failed or failed others, where others have failed me, and where we may be failing each other. Communicating in this way for me through my work is incredibly liberating.

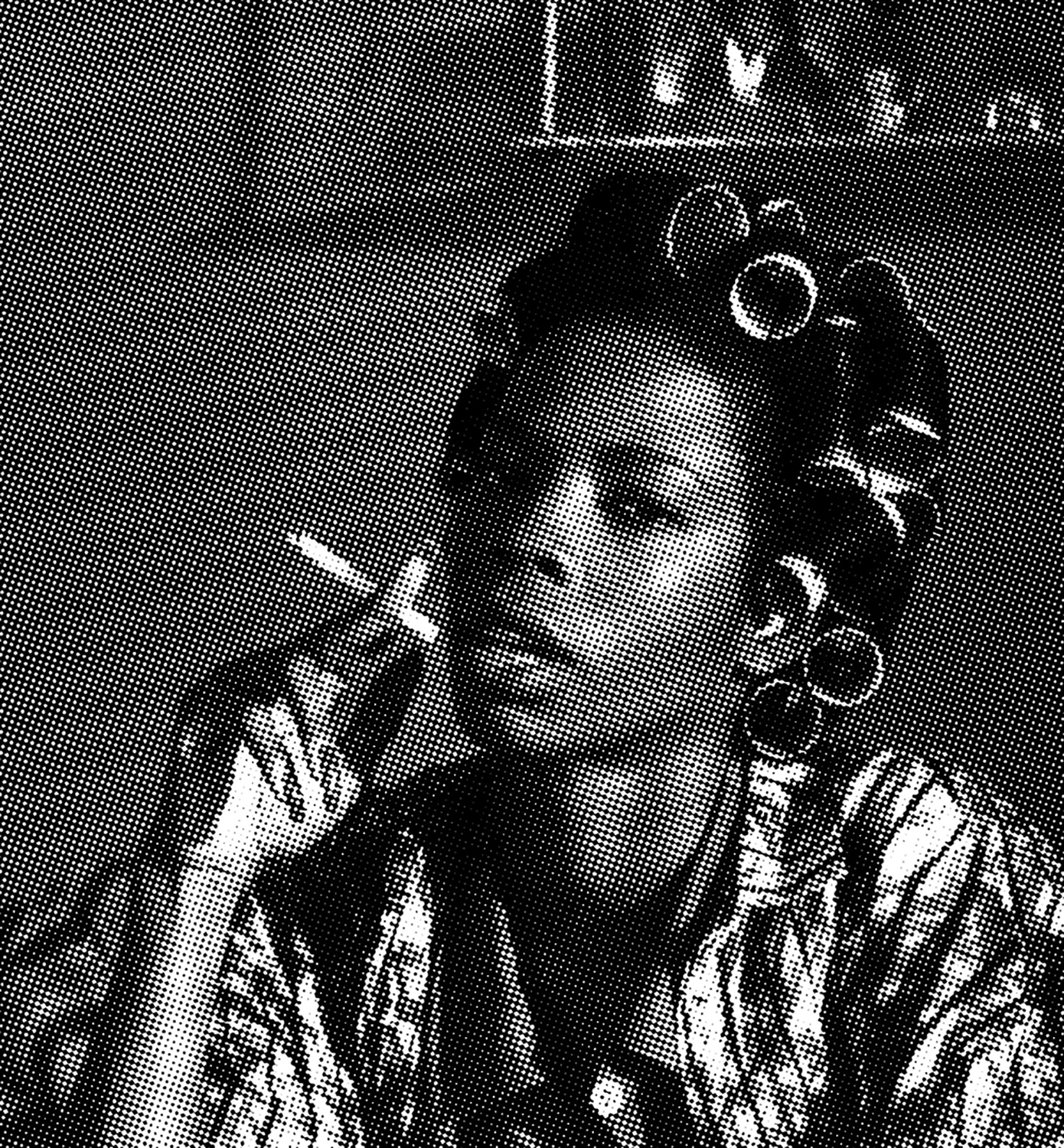

ZJM: The first series I saw of yours was Bad Selections, and I was drawn to them by their sparseness and through the culturally recognizable icon of barber shop style charts. Can you talk a bit about how you came to make these pieces?

AB: During a winter session class at the Rhode Island School of Design Lisa Young, an artist and professor of a class I was taking called Image Bank encouraged us to look to public archives as sites of intervention to create our work. People look to archives for a record of how things were. Overtime records are copied and modified. Barbershop charts that I looked at in sixth grade were different from the type during my father’s time. Yearbooks, or barbershop charts are examples of public archives, not in the traditional sense, but they can be used through and archival art practice. After learning this, I created a few pieces in this class all revolved around the theme of failure. That summer I had begun to repeat the process of creating a category “BARBERSHOP CHARTS” in my image bank, and began to excise the head from the chart transferring it digitally to a sky-blue background. I saw myself in them, who I wanted to be in the future, or when I was in sixth grade. In photoshop however I began to delete fields of the face with the select tool. I’m not into the nitty gritty details of photoshop, hence a “bad selection.” I negated those representations and the result produces and understanding of how it felt to be made fun of young, to be vulnerable, or to have your body “fail you” to some extent.

ZJM: Your alopecia areata flare up was caused by an experience of being bullied – or the experience of violence – and then your body in a way started to inflict violence upon itself. Do you see your work mixing into dialogues about violence perpetrated on Black men? If so, how?

AB: I do see my work mixing into dialogues about the violence perpetrated on black men, but I would love to believe that not all black men have violence perpetrated on them, I think that’s a stereotype I want (lol) in a utopian post-racial America, (LMAO). But the brand of American Violence inflicted on me personally, as one black male, is so pervasive, structural, institutional, economic, psychological, and emotional. There is something like 20,000,000 African American men in America, with an average age of 31 years old. Please consider these numbers rough estimates, and not alternative facts. When someone says black men, I think twenty million, or at least I will from now on. If we are all experiencing violence, so are countless other Americans, even the perpetrators of that violence. I do believe my work is involved in this dialogue, though my approach is based in my own personal narrative which if looked at through an alternate lens can be a political narrative as well. At some point in my practice I hope to address that number through a body of work that is as broad and expansive, intricate and nuanced as that 20 million. The violence inflicted on me in sixth grade was by peers who didn’t know how to understand difference. As policy makers and adults our brains can understand.

ZJM: We touched briefly on your series Dark Archives, but let's go back to it. I feel this series also touches on self-portraiture in your art. I am interested in hearing how this series begin to manifest for you?

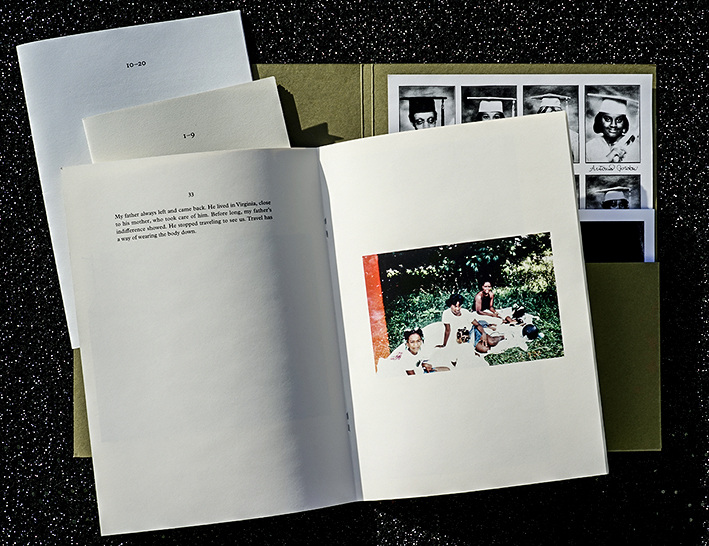

AB: Dark Archives developed around the time I was creating my thesis at RISD How To Be Good, which was also a book that critically discussed my practice and entrance into art history, but also included a memoiresqueabecedarium composed of vignettes associated with a specific letter and word. For example, A, is for Archive… It was the culmination of two years of critical and deep self-reflection. Stress. I wrote more than I needed to, designed he book myself with lots of support, and so remained in control of everything, I learned a lot from making that book. Give up some control. I was forced to however, when I had none, two weeks after graduating from RISD with residency opportunities, and very little money raised from my generous support system.

One of the residencies was the Image Text Ithaca, 2015 Image +Text Fellowship, a week long collaborative and intentionally experimental fellowship based on sharing work in development or creating work while you were there. Artist, poets, writers, and publishers all in idyllic Ithaca in a beautiful renovated barn exploring and having fun and learning from each other. It has since become a low-residency MFA program at Ithaca College. Nicholas Meullner, edited my thesis work’s text and I spoke the text along with the images I had appropriated and taken with various cameras over the past two years at RISD, and that was how Dark Archives manifested.

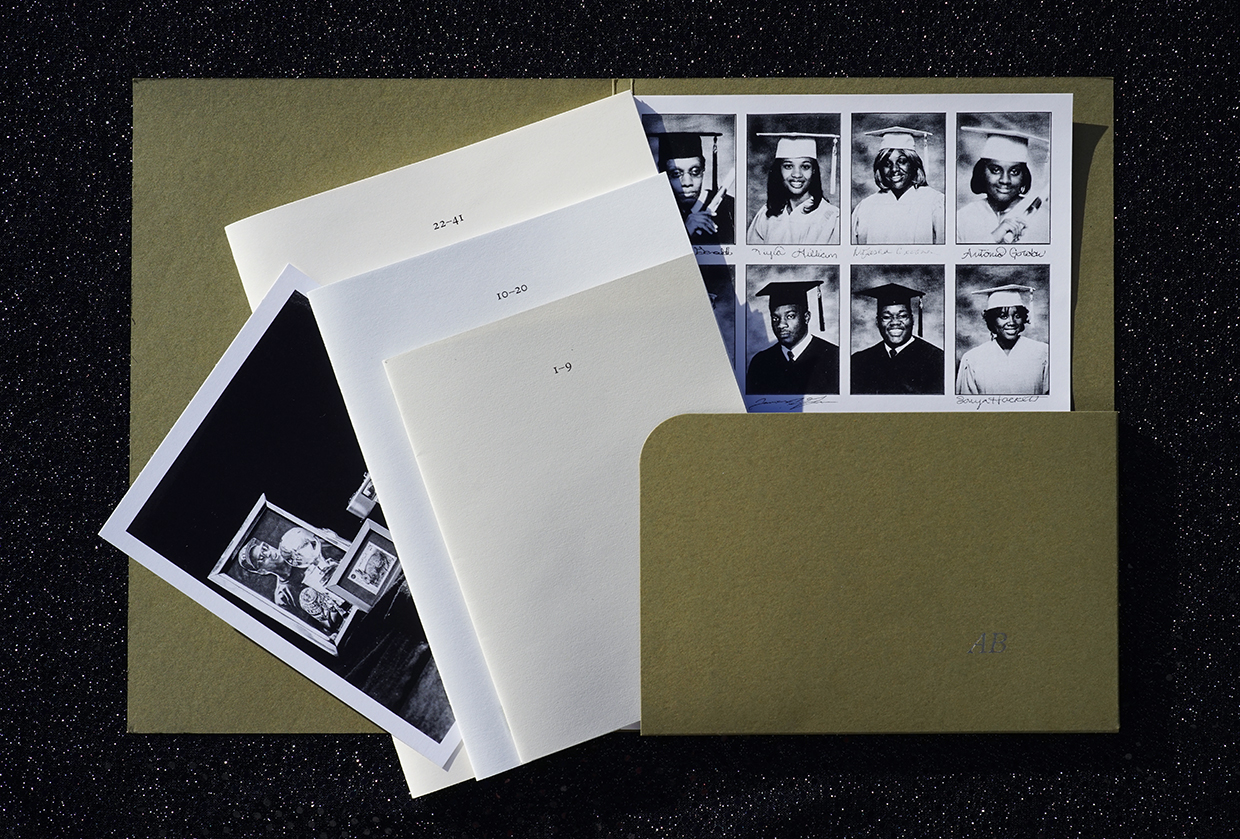

ZJM: I really enjoy the design of the book, and how it unfolds through text, images in the booklets, and then the loose images which seem to stand alone, but inform everything we see as we move through each different item. Can you touch a bit on each of these aspects?

AB: I enjoy the design of the book too! Thanks! Elana Schlenker the designer who I am so grateful to have had designed the book at the behest of the publishers because she is an amazing designer, and understood my vision and between her Nicholas Meullner and Catherine Taylor the editors of Dark Archives we collaborated with our styles and sensibilities to create something beautiful. I am so grateful to know them! Nick and Catherine are also the directors of ITI’s MFA Program, and ITIPress.

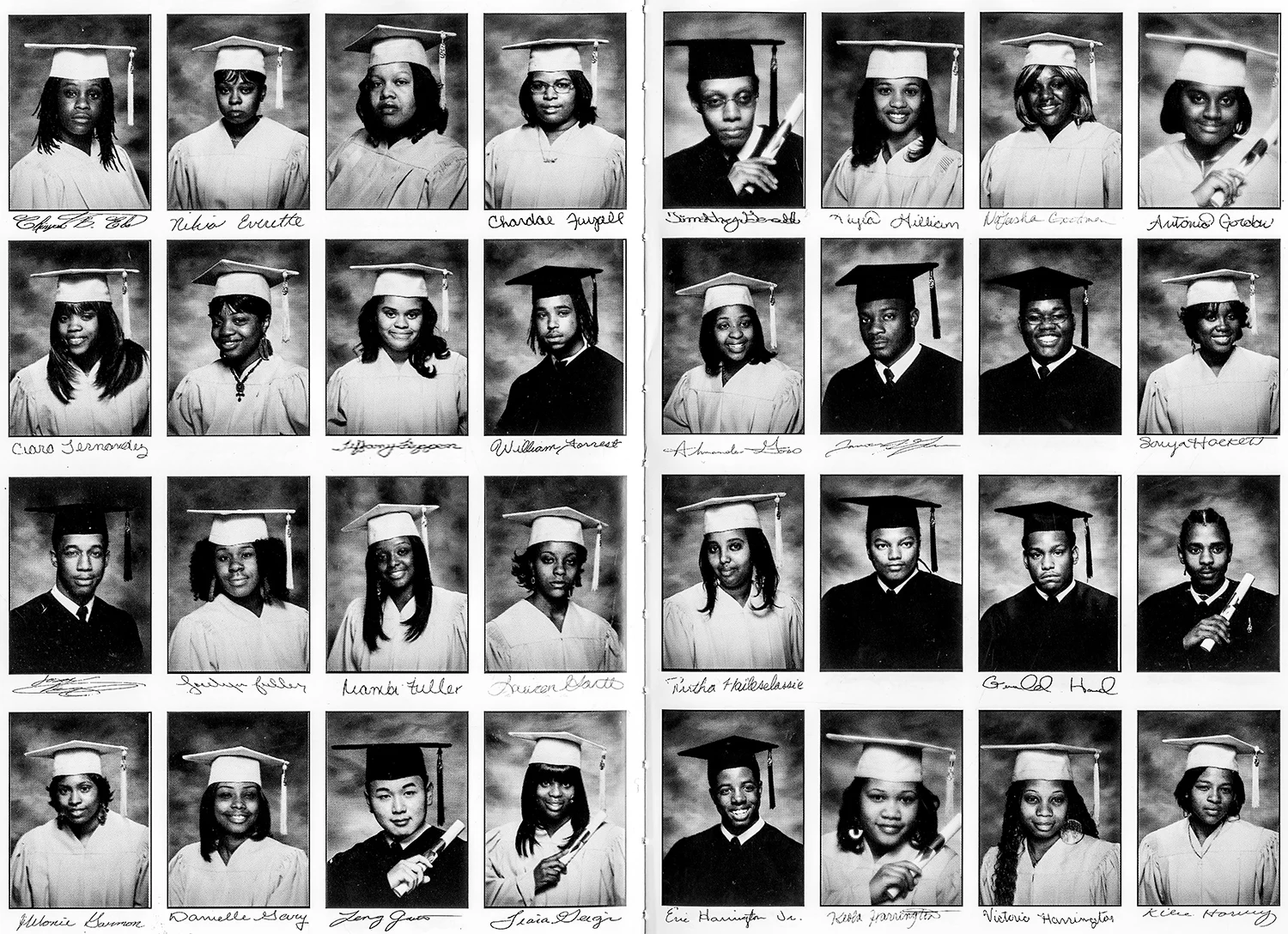

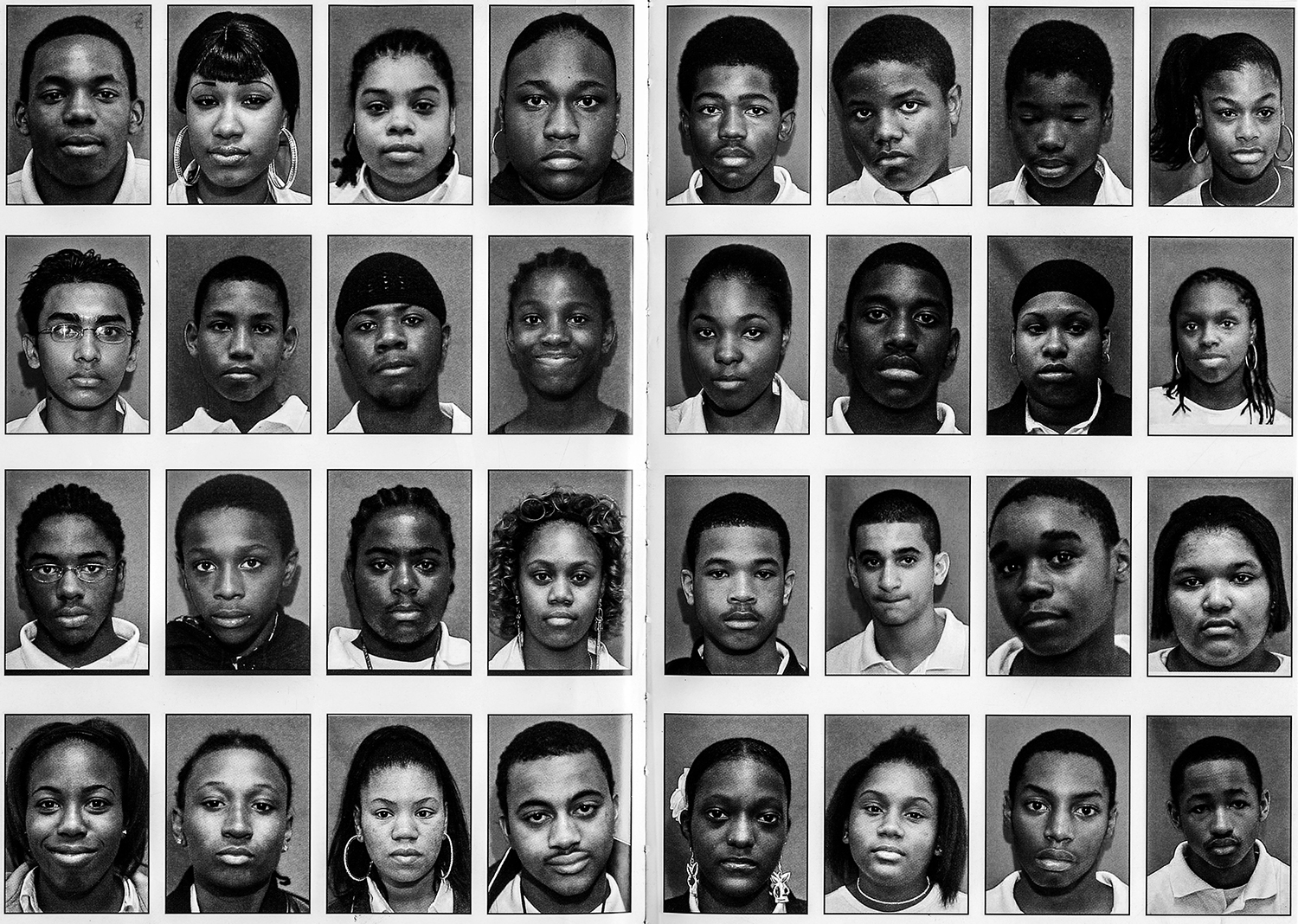

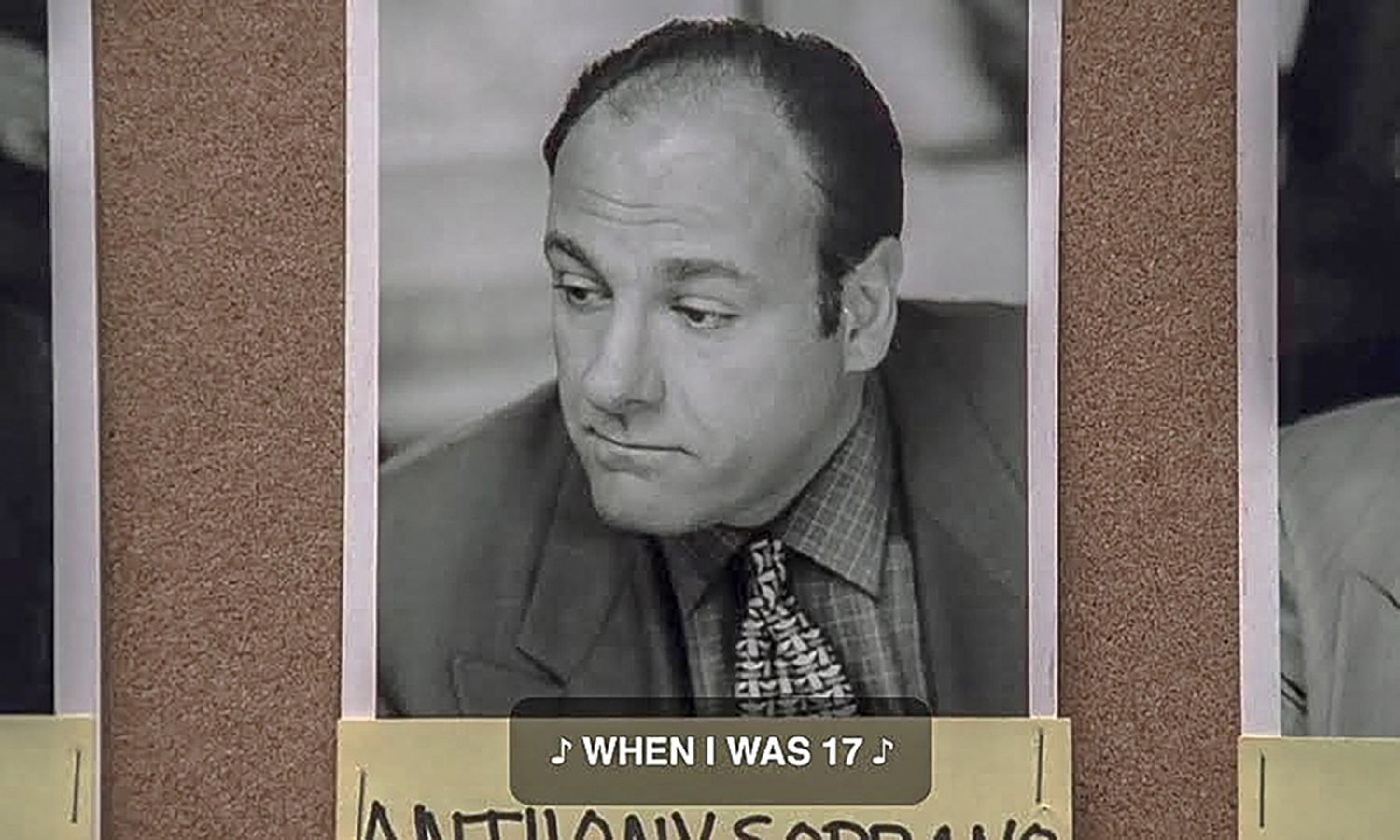

ZJM: I found the two yearbook photographs most intriguing. Standing alone, they seem fairly innocuous, but their reciprocal relationship – those who have graduated versus those who have not graduated – becomes key. The power in how these individuals are depicted definitely speaks to the power of photography, image, and stereotype. Used so simply, they are elegant and poignant. Can you tell us about your choice in including them in the series, and what they mean to you?

AB: Your description is apt, Zora. I used to travel up and down from Rhode Island on the weekends to Philadelphia to photograph and see my family. One time while I was home I noticed the year book and looked through it and notice like five double page spreads of what were 9th grade ID photos. I know because I am included in this set of photos. These five spreads were separated by another all black double-page spread that read across the gutter in yellow letters (A VISION BECOMES A REALITY…IN CAP AND GOWN) to which you turned to the images of graduates from the class of 2005. Things that have always pained me about is

1. Who decided to put the pictures in of those who did not make it (9th grade ID photo that people interpret to look like mugshots) Through to the end? Maybe a yearbook committee of teenagers proud of themselves and trying to further raise their self-esteem?

2. Who decided on the phrase “A Vision Becomes a Reality… In Cap and Gown”? Its powerful I think that someone believed that those who had dropped out (if all of them even did) did so intentionally, like it was their personal “vision.” Maybe the yearbook committee? (This in fact for me was true, however, I wanted to leave, because I wanted to learn where I could get support and care.)

3. Who signed off on the yearbook and missed those decisions to shame and embarrass those who failed for reasons unbeknownst to them? Definitely an adult.

I chose to include them because it makes me cry to think about how we were taught to think about one another as teenagers and that the adults in our lives THE ADULTS EDUCATING US did not step in to teach us to love on another. But I could be being dramatic.

ZJM: By accessing family photographs and incorporating it with your reflections on self, it seems as if you’re reinterpreting an already existing archive and making a new one. What was it like to work with your family archive, and what does this reinterpretation of it mean inside of the series?

AB: I take photographs in many ways, one of them being appropriating them, this time from a family archive of them. I must say here that my relationship to that archive has changed drastically since Dark Archives was published two years ago. The archive existed photographically, but there is a text archive there that has never existed I believe because there has only and will only be one Andre Bradley. Another one of my professors in graduate school, Ann Fessler, instilled in me a belief that my story is more important than Michael Jordan’s. I’m being tangential but the point of that was to say that I had to find my story within my families’ photos, not their story of me, or my peers’ or my countries, my own.

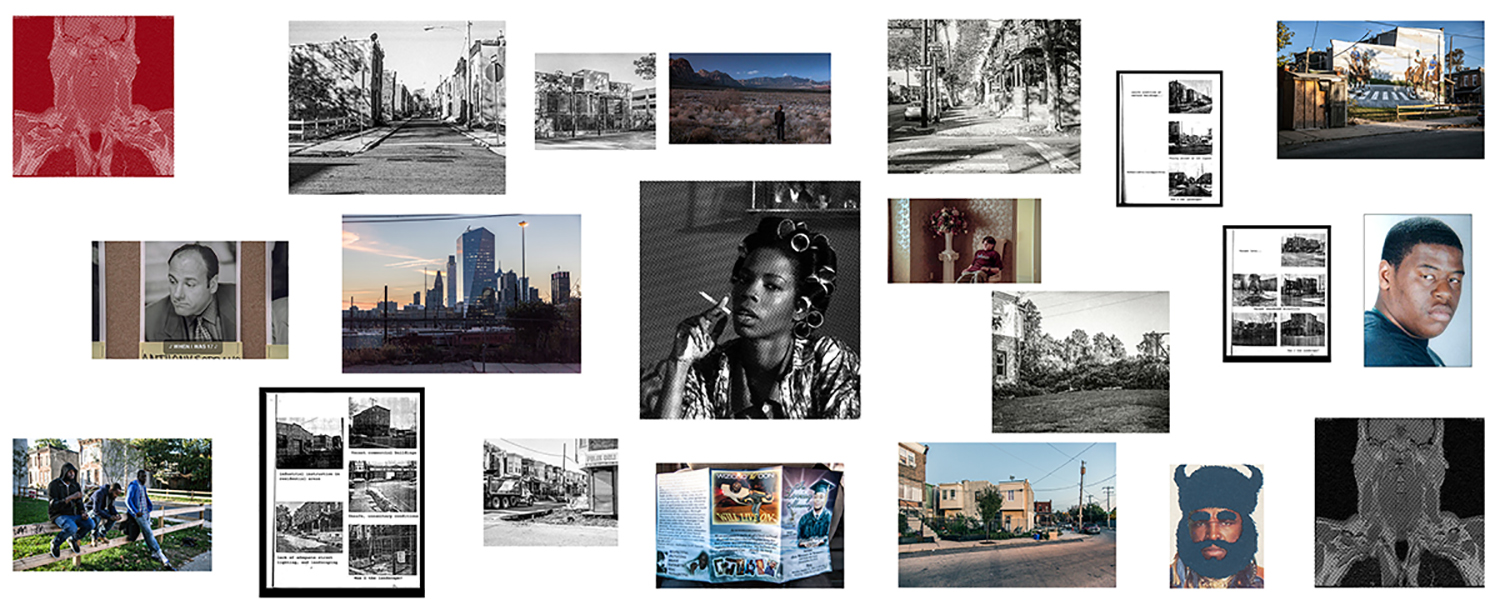

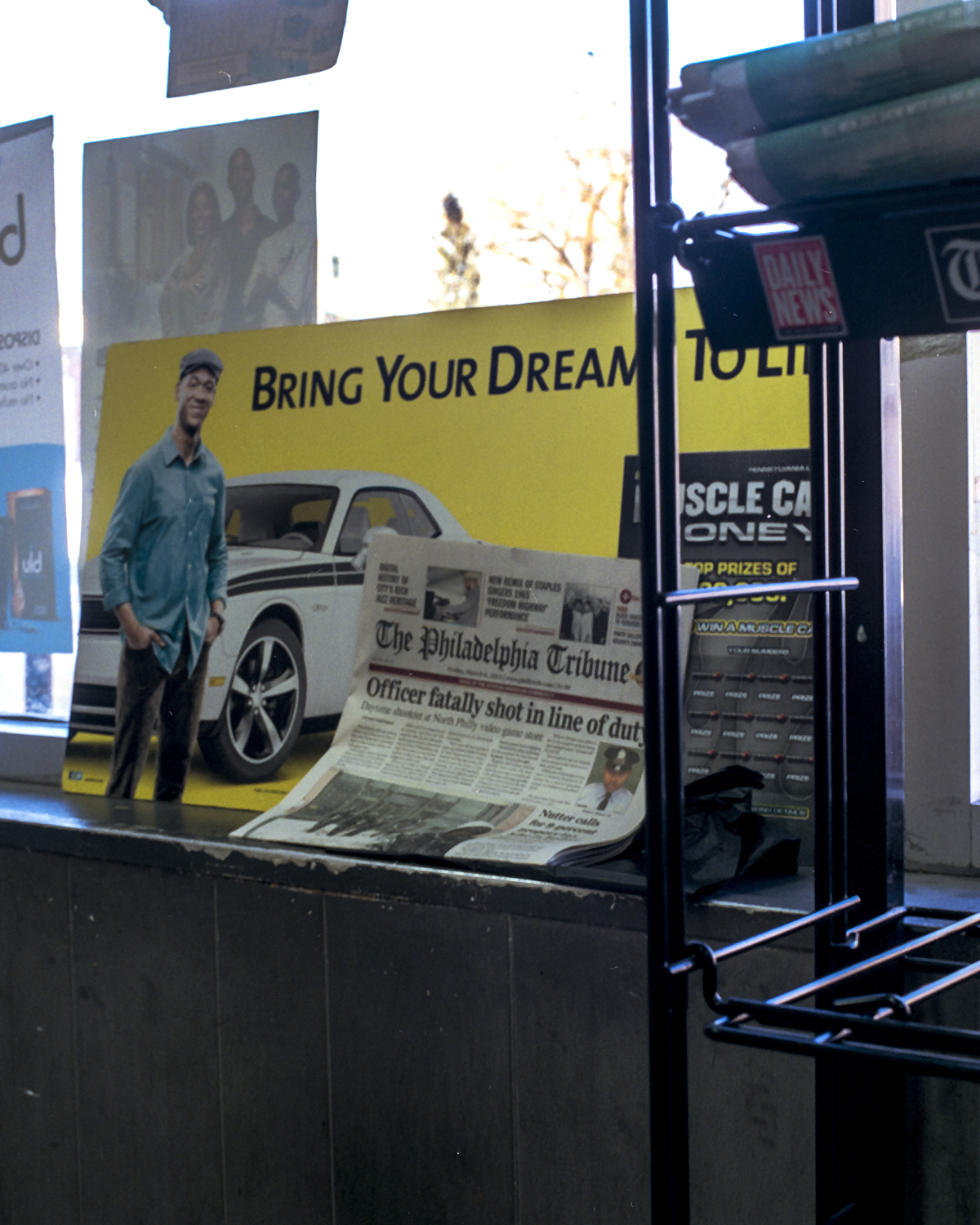

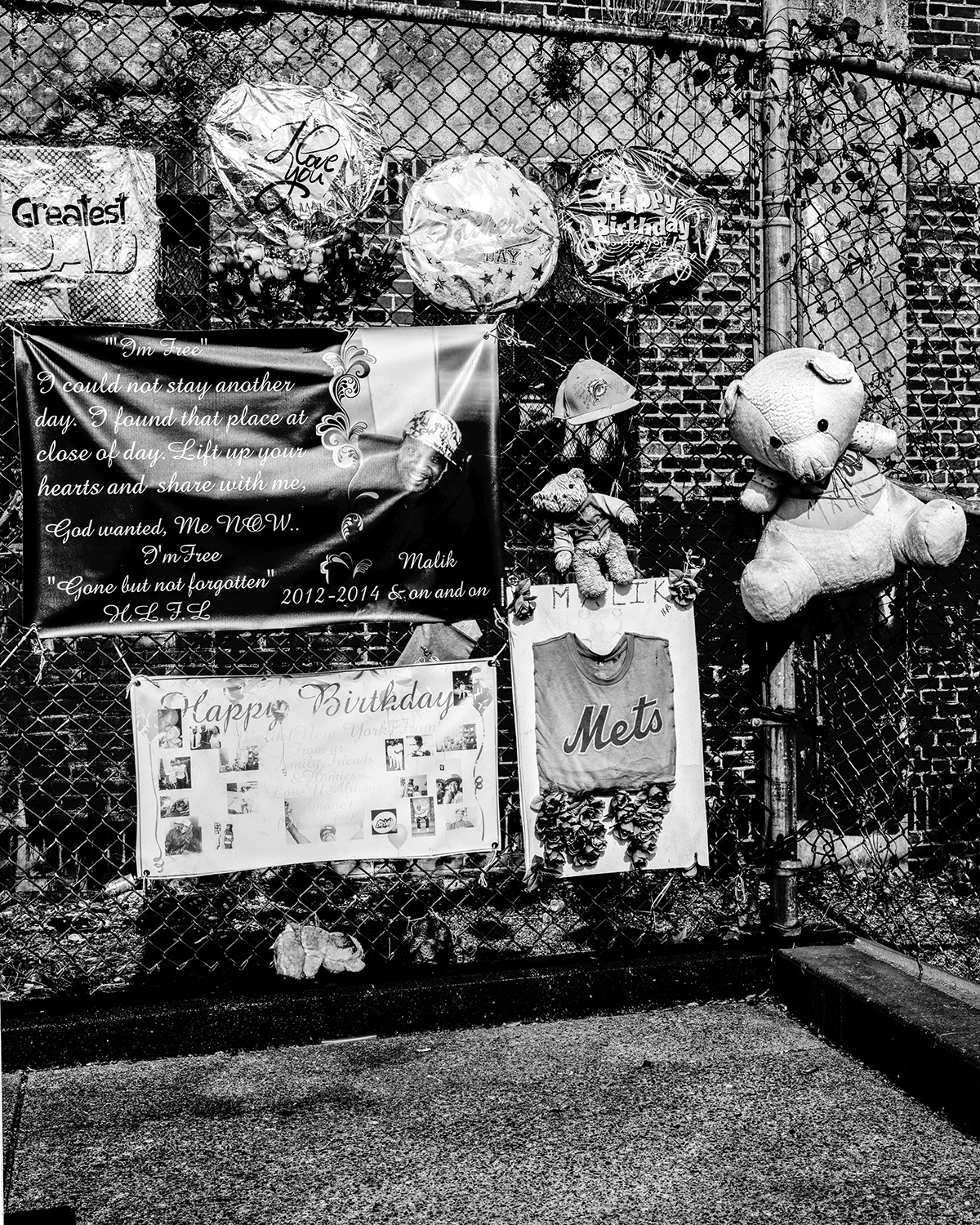

ZJM: Your last series I wanted to discuss is Naive Format. In a way, it takes the book format, and expands it out for us in a tableau. A book typically asks us to engage with information in a linear way, each sequential image playing off the previous and providing a building block for what comes next. What was it like to change the format of readability?

AB: In Naïve Format amongst several things, I wanted to convey a sense of my mental state at a point during its creation, I was agoraphobic when I was making it and I was horrified of walking outside, When I did, I couldn’t focus on one thing. Another one of my professors at RISD, Steve Smith, taught us about drawing with space. In the images, I did take my relationship to the space is distant, and I am drawing as an outsider, I had just moved back to my hometown. When I was in the house so much, it was in a room with a mirror in it that matches the dimensions of the seminal print. To change the format of readability was related to what I wanted to say, which is related to the title. In this work, I think a lot about the landscape of where I grew up and not only my past there but my now as well. As I’ve grown and learned to define things on my own terms (IE my ownership of and relationship to the global landscape I inhabit, as it relates to Naïve Format) landscape is also a type of photograph and orientation of a print, landscape as format. In making this work I realized how “green” or naïve it was of me to believe that my education would make me a savior for my family or society.

ZJM: You’re also working with the archive again, bringing in found imagery and mixing it with your own. How do you intend for the viewer to engage with the information provided?

AB: In this work, I was encouraged by the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center to create in ways that were comfortable for me, familiar, but to push my limits a little. In this form, there is no text to accompany the landscape of images. There is a normal artists statement. I intend for the viewer to question its authenticity as a work of art, just as my authenticity is questioned in everyday instances of my life as a black man. I intend for the viewer to have questions regarding the value of such a thing as a creation, let alone an important work in the fine art realm of photography. Most importantly to me I intend for the viewer to look, no matter how long. To look but not engage I think, is a missed chance to confront yourself or an artist. Confrontation can be vulnerable, positive, transformative, and challenging.

ZJM: In Naive Format, you talk about personal fears, and these fears “igniting questions”. One question that stood out to me is, “what does the landscape communicate to us as men”? I’m assuming you’re referring to the landscape of Philadelphia, but can you expand on this question a bit, and how you feel the work begins to answer it?

AB: I was wondering here about my relation to the landscape of Philadelphia and how others who do or do not look like me but are men experience this landscape, emotionally, psychologically, physically. I am not solely speaking of Philadelphia but I am referring to an interior zone of expression, where one gives themselves permission to express fears, longings, desires, failures, and their power. I believe this work was an attempt at beginning to answer this question. Our interaction with these expressions I think directly relate to our behaviors or abilities to function positively or negatively in public, maybe that’s a duuh moment but…and what’s respectable is also another conversation.

ZJM: What’s next for you, Andre?

AB: I’m taking a break from speaking and starting to put together the foundation for a new body of work, but also rethinking career choices, my art practice, and its relation to my impoverished neighborhood and the billion-dollar industry in of commercial development underway next door to it. I’m going back to school. For an MBA, then a PHD.

ZJM: Thank you for taking the time to speak with me.

AB: Thanks for the invitation Zora, I appreciate it! Hope to connect in person someday soon.

FOOTNOTE

1. Xscape, “Understanding” Hummin’ Comin’ at ‘Cha, 1993

All images © Andre Bradley