Q&A: Amy Elkins

By Zora J Murff | Published January 19th, 2017

Amy Elkins (b. 1979 Venice, CA) is a photographer currently based in the Greater Los Angeles area. She received her BFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York City. She has been exhibited and published both nationally and internationally, including at Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna, Austria; the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, AZ; the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; North Carolina Museum of Art; Light Work Gallery in Syracuse, Aperture Gallery and Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York, De Soto Gallery in Los Angeles, the Houston Center for Photography in Houston, TX among others. Elkins has been awarded with The Lightwork Artist-in-Residence in Syracuse, NY in 2011, the Villa Waldberta International Artist-in-Residence in Munich, Germany in 2012, the Aperture Prize and the Latitude Artist-in-Residence in 2014 and The Peter S. Reed Foundation Grant in 2015.

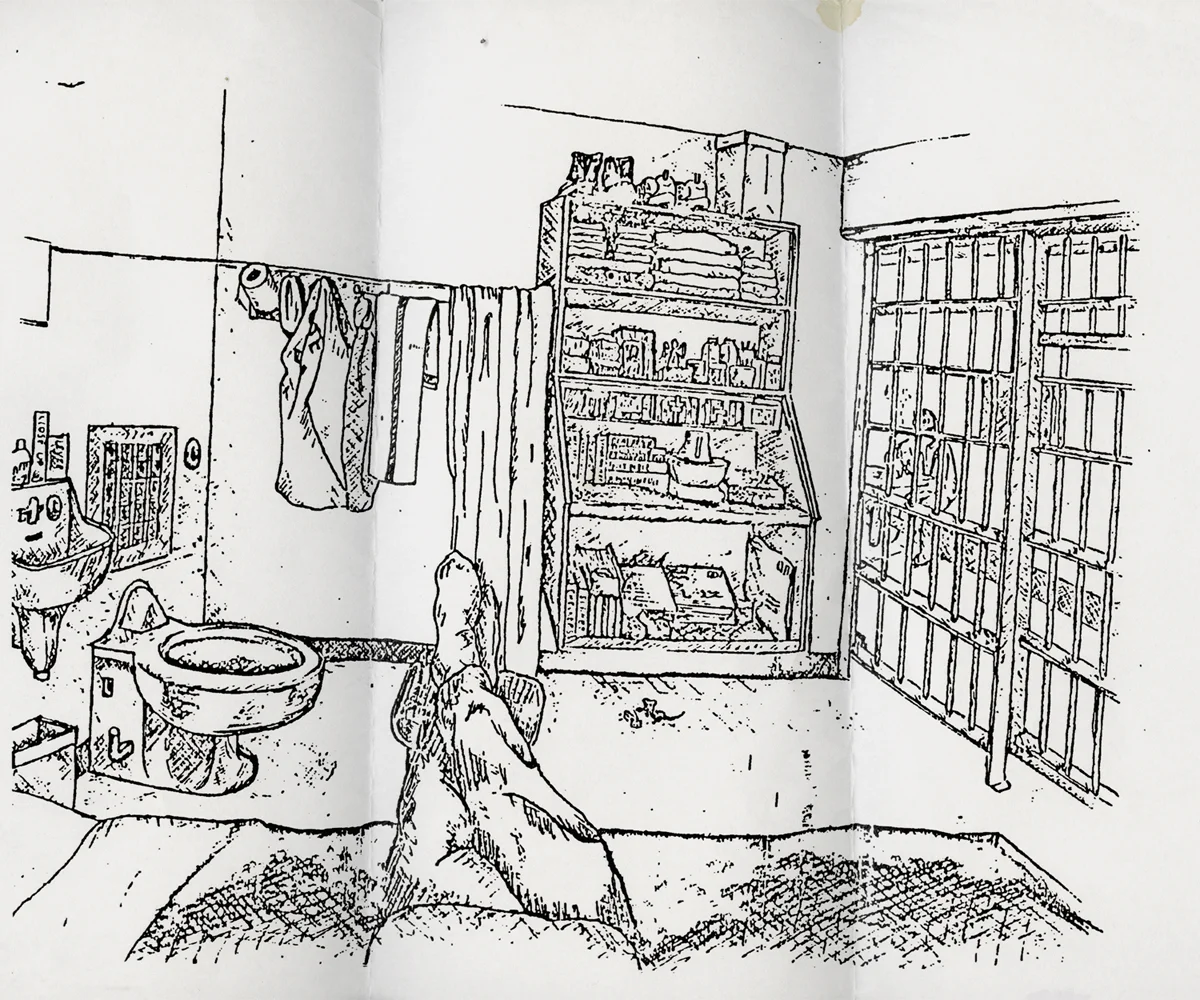

Cement Study #2

Zora J Murff: How did you get into photography?

Amy Elkins: I studied art, photography and liberal arts for several years at a local community college. After exhausting all of the classes I could take, I saved up and went on a 45 day cross country road trip with my closest friend to write and make photographs. Shortly after, we moved to New Orleans, where I would end up living for several years. There I met and was mentored by the famous jazz photographer Herman Leonard. He was 80 at the time, I was 21. He told me endless stories of being my age and heading to NYC to become a photographer and eventually he pushed me to go there myself. In 2004, I moved to NYC to attend School of Visual Arts. I graduated in 2007 and have continued to make photographs ever since, almost all of which have been an exploration surrounding masculinity and male identity.

ZJM: When you say that most of your photographs have been an exploration surrounding masculinity and male identity, your series Elegant Violence comes to mind, and the implication of masculinity and violence obviously makes me think about your series Black Is The Day Black Is The Night. What was your initial drive to focus on male identity, and how do the two connect?

AE: Over the years I have had several family members get swept up in the prison system. I suppose that did play a role. But it more so stemmed out of my ongoing exploration in masculinity and at the time…what I was trying to research further..the idea of hyper masculinity. When I first stumbled across the pen-pal websites that lead me to work on Black Is The Day Black Is The Night (BITBITN) I was working on a portrait project with ruby players. I had turned to rugby because I was fascinated by how barbaric and violent the sport was. When I first started writing those in BITDBITN, I was wanting to explore why men seem so much more prone to violence (either play violence on a field or actual violence) than women. I wanted to see where the drive towards violence began in their lives and how much of a role violence played in their upbringing. The project, of course, took a very different turn, but that was the initial intrigue. As it would be, none of them wanted to discuss their crimes or what lead them to commit them. Some of them only spoke of their innocence…some only spoke of the impacts prison and living in isolation had on them. I was looking to “speak” directly with those who had been convicted of violent crimes only to find that they were all more broken down and poetic and introspective than I could have imagined. Almost all of them spoke of being raised in poverty and most with families riddled with dysfunction. They spoke of their living conditions in prison, the length they had spent in isolation (which by the time I wrote was already between 13026 years), the books they read, the food they ate, the uniforms they wore, the amount of times they were permitted out of their cells, etc, etc. All of which made me want to research solitary confinement and the death penalty even further. The more I researched, the further I dove into the project.

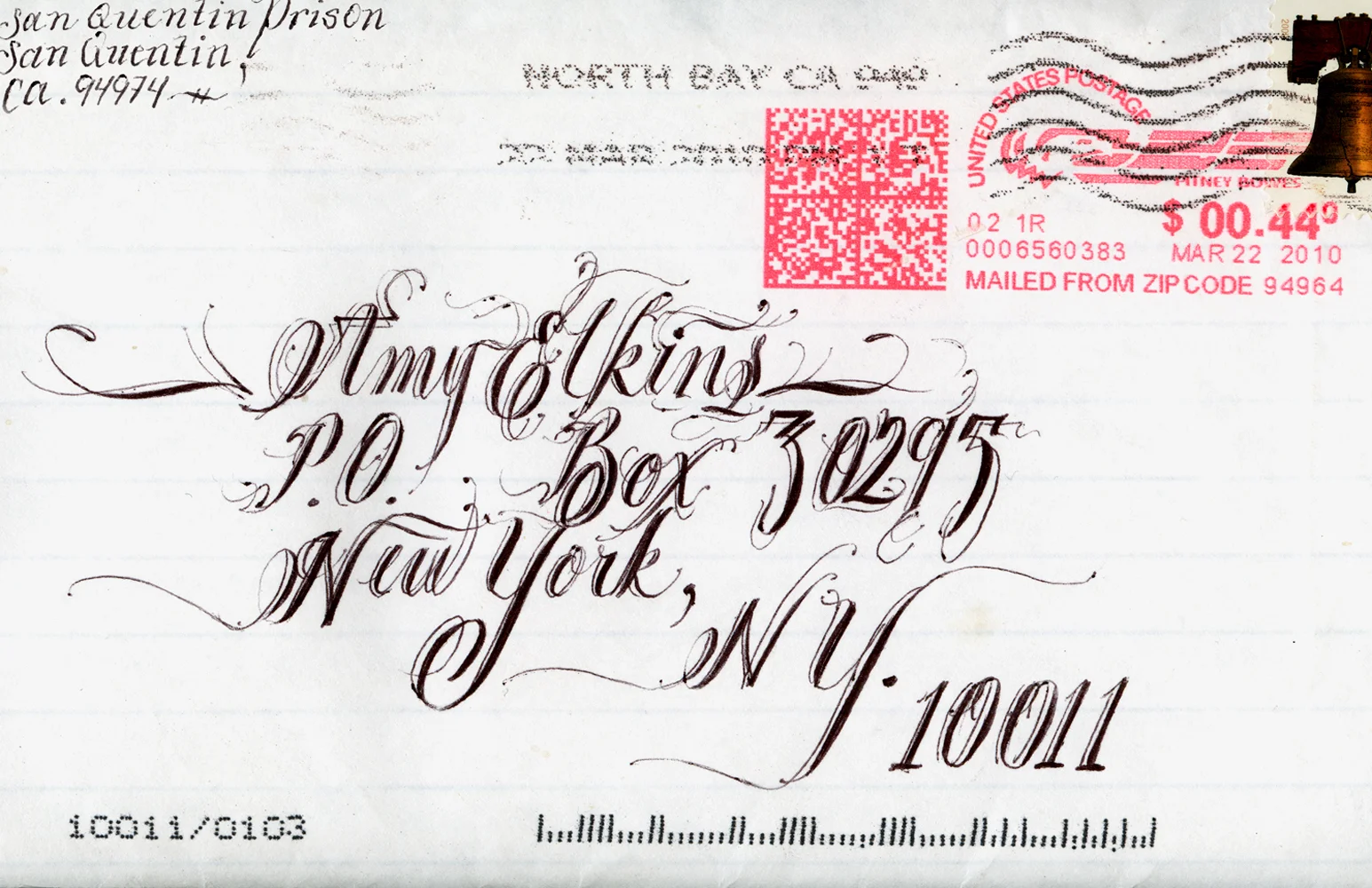

Envelope Art Sent from Death Row, San Quentin

ZJM: This project is ambitious, how long did you work on it?

AE: I set up a PO Box and started writing to the men in BITDBITN in 2009, though photographic work didn’t come right away. Letter writing included, I worked on the series from 2009 until when the book was published several months ago (2016. I wrote letters and made work most intensively between 2010-2012, though some letter exchange when on until 2014. I worked on piecing the project together in exhibition form in a larger way in 2014. The exhibition ended up traveling and growing for nearly two years. I ended up making more pieces along the way (a video piece, an installation of a solitary confinement cell, a library installation, etc). I went on to look at the work and the scope of the letters even more intensely when I started working on the book with a designer in 2015. There were many times throughout all of this where the project got too heavy and I took breaks. All in all, I worked on the project for 7 years. Over that 7 years, two men were executed and two were released.

ZJM: What was it like sending out and receiving those first letters, and then forming relationships with these individuals over the following years?

AE: It was intense of course. And a little nerve-racking. I had no way of knowing who, if any, would write back. It was a little like sending out a message in a bottle. But to my surprise, letters started coming in fairly quickly and I suddenly felt this pressure to keep up. Some of those relationships developed a bit more organically than others. Some always kept a guard up. Some wrote far more frequently than others. I was working with seven very different personalities and writing styles. It made me think about my own day to day life so differently. In a lot of ways, it heightened my senses… because I could write with a lot of description to people who would never be able to have my experiences. Two of the seven (one serving a death row sentence that was carried out in 2012 and one serving a life sentence in solitary confinement) wrote the longest and most personally. Their letters resonate the most.

ZJM: Let’s talk a little bit about the book. When did you begin seeing the project taking book form? Can you share some details about your sequence?

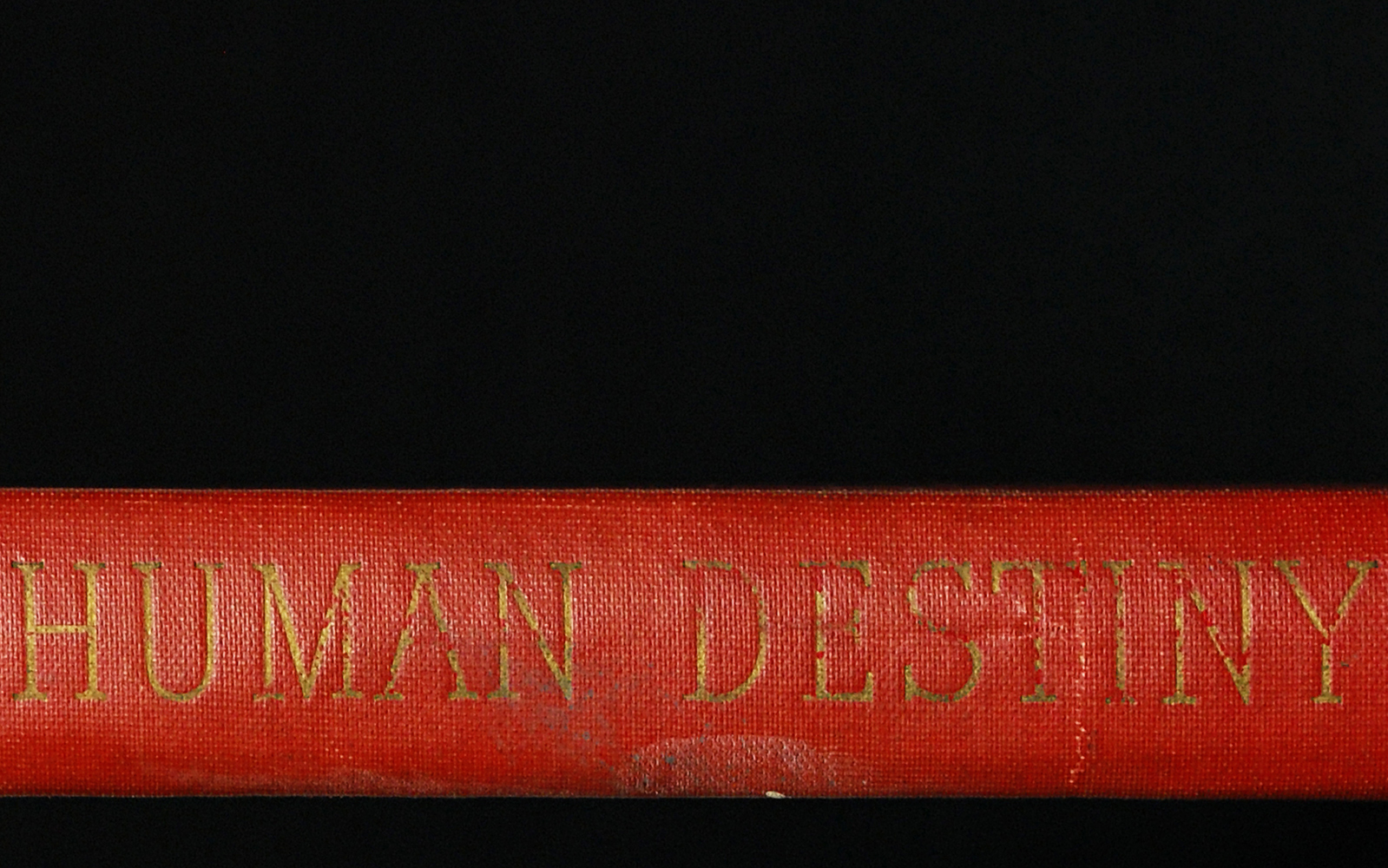

AE: I always sort of saw this as more of a book project than anything else. It’s just such a dense project that I’ve always found it hard to exhibit and have enough caption info for the viewer to be able to navigate it all. A book is able to hold all of that in a way that is so much more profound to me (and hopefully to the viewer as well). The sequencing is meant to be both rhythmic and disruptive, poetic and stark. It is supposed to mirror the complex nature of incarceration. The sequence leads the viewer slowly through all seven stories, ending with the denial of stay that resulted in one of my pen-pals being executed. I worked on the book for a full year with an amazing designer, Ania Nalecka, and we really tweaked every detail of the book to be conceptually tied to the work. A few examples: The book was designed both softcover and the size of an average paperback novel with maximum security prison book and mail regulations in mind. The red stitching that binds that book mimics the red ink on notebook paper, but is also meant to scar/interrupt the images in the book the way security screening stamps often scarred/interrupted the handwritten letters I received. There are many small details that went into the book like this. It was really a wonderful experience to be able to make a book exactly how I wanted to.

Prison Food Tray acquired from Ebay.

ZJM: With my own experience of being a social worker – dealing with and eventually making work about peoples’ lives in an intimate way – and it is easy to understand how BITDBITN came with some emotional weight. By immersing oneself into the series, we know what these images ultimately mean, someone is going to die. We can feel this weight, but the conceptualization of the process is nothing short of beautiful. I would be interested in hearing your thoughts on beautifying oppression, violence, and death? Does it help us look? Help keep us engaged?

AE: I think that art is a very valuable tool in helping society digest hard topics. It makes it far more accessible and open. And while I was making work organically and not thinking of where it would go as it was in process, I do think that the resulting approach has helped people to look, connect and engage. I’ve witnessed this at openings while watching people engage with the work. I’ve seen people react emotionally… and in witnessing that I’ve also realized what a large artist guard I’ve had to put up in order to make this work.

ZJM: Do you feel your images open space for contemplation?

AE: I would hope so. In all of my work, it is my goal to present things and have the viewer be triggered to question their own beliefs, their own views, their own need to label things in the world around them. In BITDBITN, I don’t speak that much about my own stance on the death penalty or solitary confinement, but presenting the information (either on the wall or in a book) asks the viewer to contemplate their own stance on the subjects. I’ve seen people in that space of contemplation while looking at my work, some more emotional than others. I know it’s a heavy, heavy subject and I’ve gotten enough reaction to feel that it does indeed leave space for contemplation. I’m humbled by it every time I witness it because it’s not just a reaction to my work, but a reaction to much larger topics. If my work can do that, I feel like it has purpose.

ZJM: What’s next for you?

AE: I’ve been really enjoying returning to portraiture. It’s a huge passion for me. I’ve been spending the past year making small trips to Georgia to make portraits that shake up stereotypes that surround masculinity in the South. It’s all very new, so that’s all I can really share for now. But I am excited with the way it’s shaping up and can’t wait to shoot more.

ZJM: Thank you for taking the time to share some of your insights with us, Amy.

AE: Thank you!

To purchase a copy of Black Is The Day, Black Is The Night and to view more of Amy's work, please visit her website.

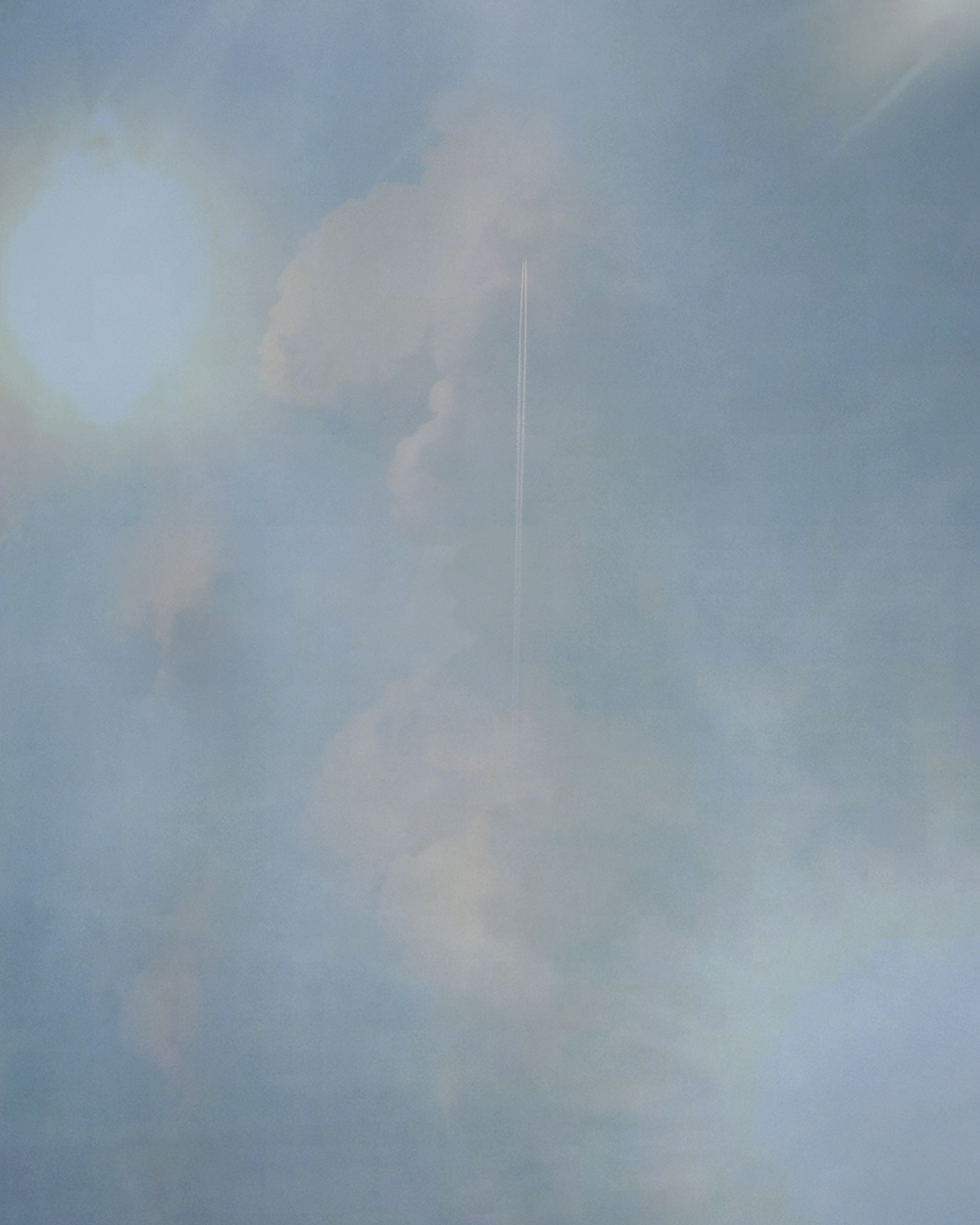

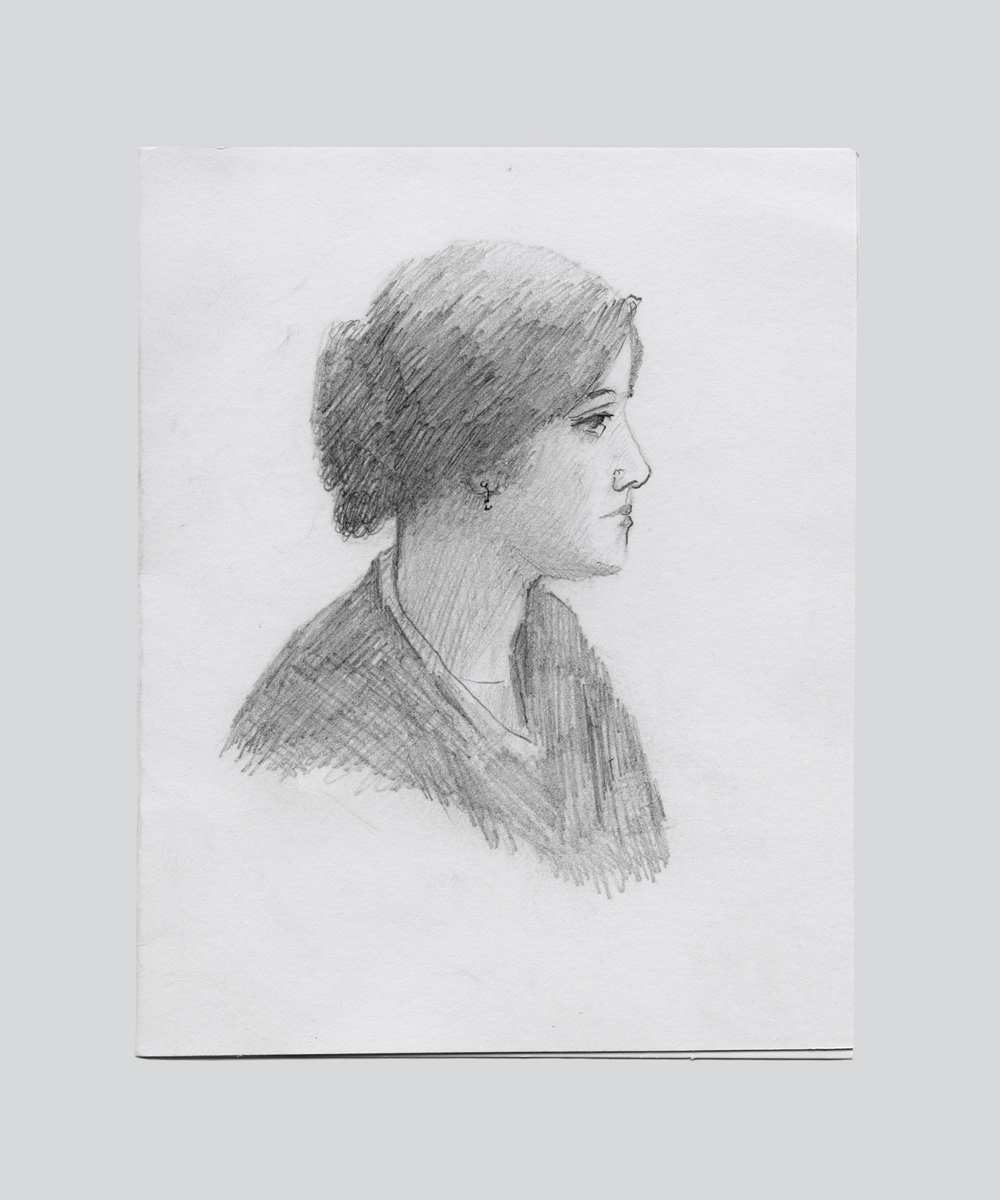

14 Explosions, September 22, 2009 6:22 p.m.

A piece created as a reaction to a penpal’s execution by lethal injection, which went through September 22, 2009 6:22 p.m. His first letter came less than four months before his death. In a poem he once wrote - “Metamorphosis is complete, illustrious beauty, unique.”

All images © Amy Elkins