Q&A: Abbey Hepner

By Zora J Murff | Published on July 20th, 2017

Abbey Hepner is an artist and educator investigating the human relationship with landscape and technology. Her work explores ethical gray areas where humanity and industry collide, illuminating the increasingly common use of health as a currency. She received degrees in Art and Psychology from the University of Utah, an MFA in Art and Minor in Arts Management from the University of New Mexico. She teaches at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs and is the founder of Creative Advocacy, an organization dedicated to teaching artists professional development skills.

Hepner’s work has been exhibited widely in such venues as the Mt. Rokko International Photography Festival (Kobe, Japan), the Museum of History and Industry (Seattle, WA), SITE Santa Fe (Santa Fe, NM), the San Diego Art Institute (San Diego, CA), the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History (Albuquerque, NM), Gallery of Contemporary Art (Colorado Springs, CO), Institut für Alles Mögliche (Berlin, Germany), and the Newspace Center For Photography (Portland, OR). She is the recipient of a Puffin Foundation grant and has presented at numerous conferences including the 2015 International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA) in Vancouver, Canada, and the 2016 and 2017 Society for Photographic Education (SPE) conference.

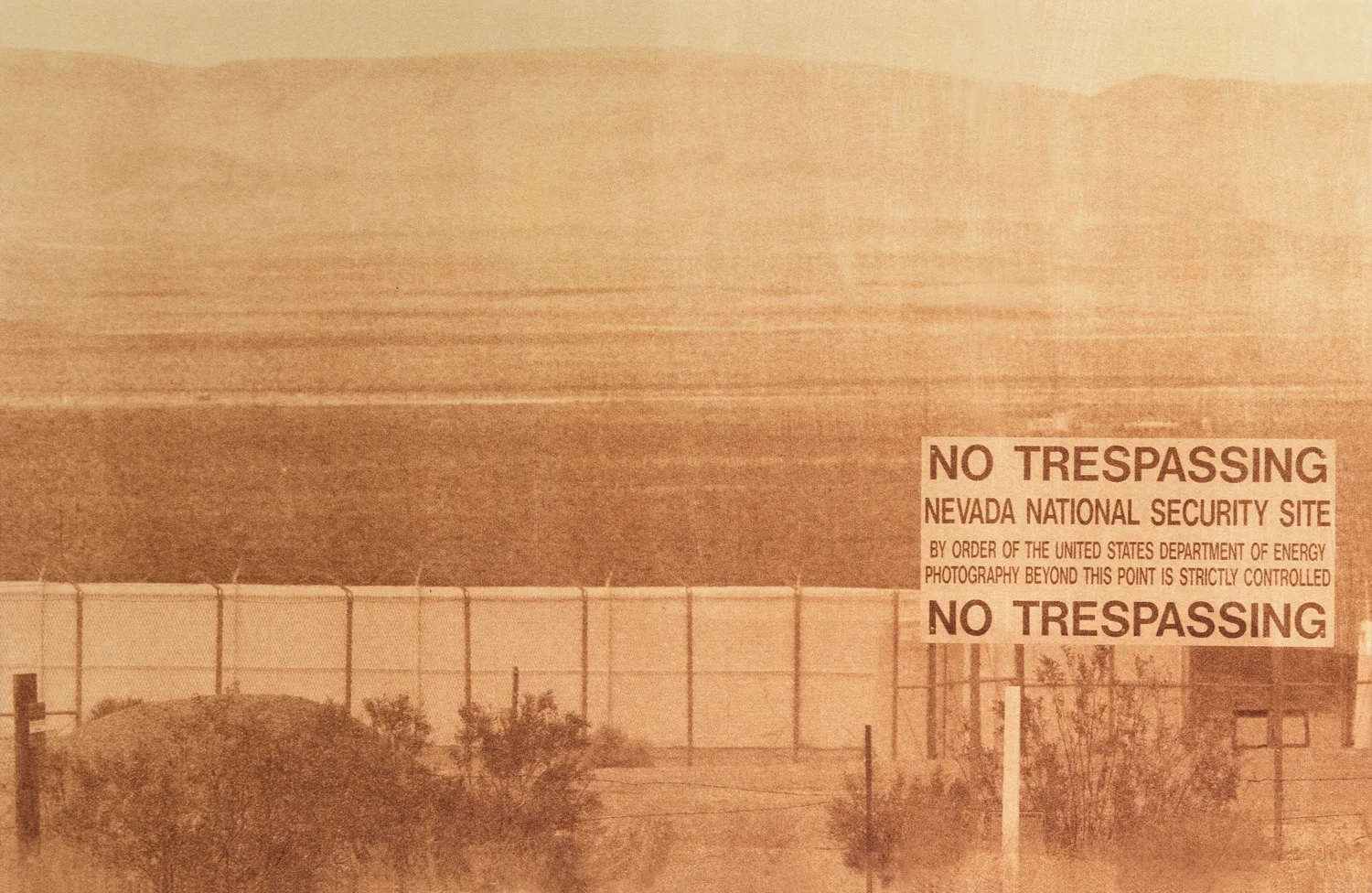

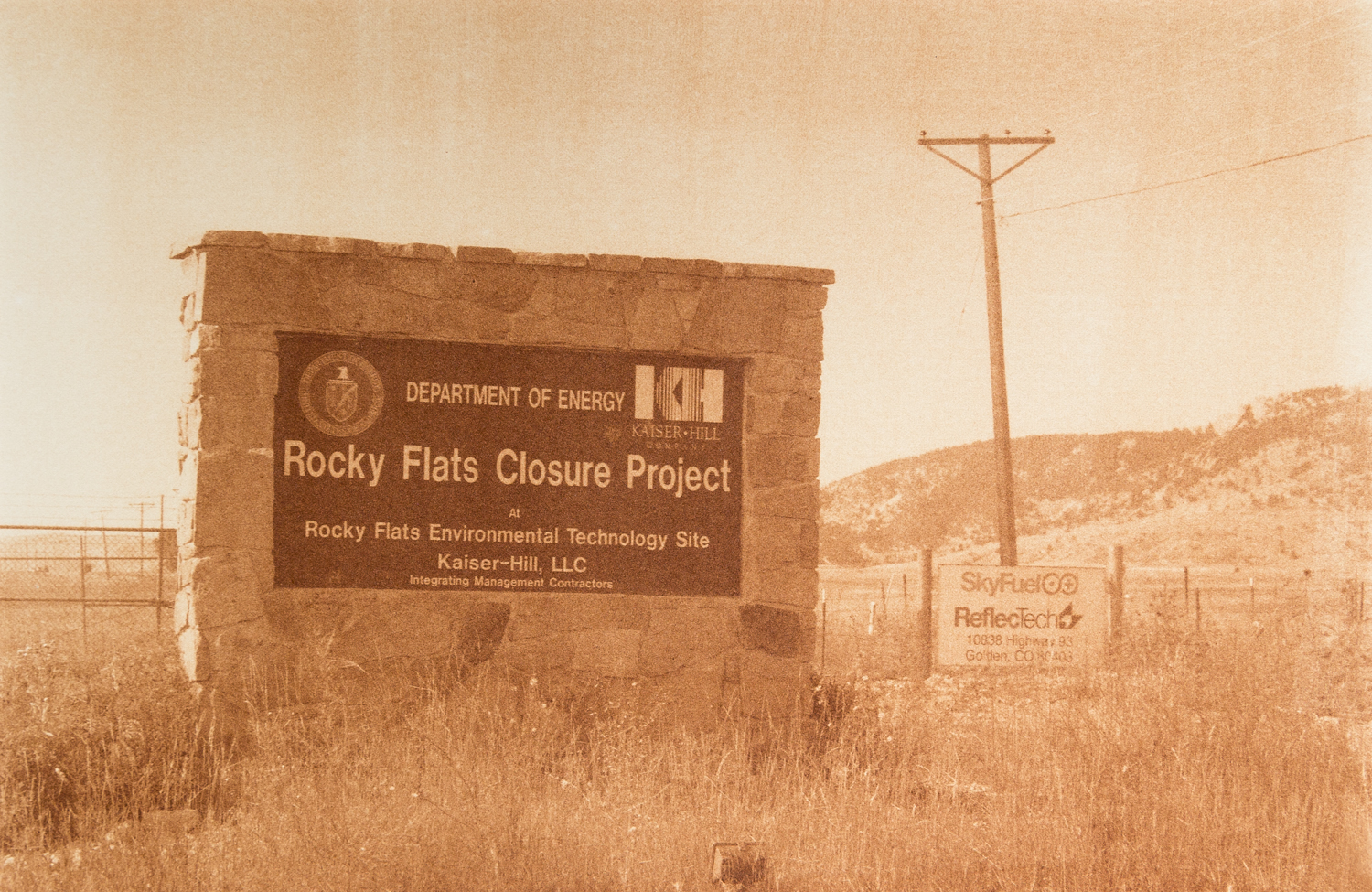

Nevada National Security Site, Outside of Las Vegas, Nevada, Radioactive waste shipped to WIPP: 107,087 Gallons

2014, 9”x13” Uranotype (uranium print)

Zora J Murff: Hi Abbey, thanks for joining me for this interview. Let’s start by getting to know a bit about you.

Abbey Hepner: Thank you Zora. I have a background in cognitive psychology and worked in the field for a few years before focusing on art. What compelled me to study both was the desire to make the invisible visible and to confront the paradoxical and often taboo things that make us human. I focus on health, toxicity, and fear, and the systems of power that are involved with those issues. My work probes at ethical gray areas and I work with subject matter that I have deep personal connections to both sides of. Art has been a safe haven for exploring cognitive dissonance and has also has grounded and connected me to other people through acquired beliefs. I have almost no family history, moved around constantly growing up, and lived abroad for a few years. I understand what it means to be both an insider and an outsider and I use this experience to seek answers through a different psychological lens.

ZJM: On your website you state that your, “work investigates the human relationship with the landscape and technology.” What about these topics drew you in to making this type of work?

AH: Our immediate environment influences our health, the things we eat, the way we dress, and the way we relate to each other and the world. There’s a certain existential void that exists when one isn’t grounded to a sense of place, and that void is a part of our modern, mobile world. We have little control over the way our environment is transforming and that is largely because we have ignored the embedded history of place and its cyclical nature. We rely on technology to make up for what we lack, to fill a void, and to fix what we have destroyed. What happens when technology fails us? That question interests me because technology has the ability to shape our mental and physical health more than ever, and our reliance on it determines what we leave behind for future generations.

We can look at the technological tools that a society uses to determine where it places its values. Is it on the health of the people or on the GDP? Does it equalize risk or is power exercised at the margins? One of the first projects that I did that inspired me to investigate landscape and technology [Scars On The Landscape] was created in Germany at the height of the decommissioning of nuclear power plants across the country. I was interested in what the landscape becomes after the towers fall and the buildings become inoperable. The industrial landscape is suddenly rendered impotent, but the land often remains dangerous for decades. Creating that work opened my eyes to many problems with nuclear energy that I wasn’t aware of and it made me conscious of how nuclear propaganda is deeply embedded in our American culture.

While my work often questions our reliance on certain technologies, I also recognize that technology is socially constructed and I am interested in how we create boundaries to protect ourselves. Psychologists like Stanley Milgram and Sherry Turkle have shown that we are really bad at recognizing when something has gone too far. We obey authority and are easily allured by things that cause us great harm. I’ve had to remind myself of these limitations while making work inside a nuclear power plant, in a neuropsychology lab, and with caretaker robots. I’ve never experienced that deep sense of grounding to a place or a group of people, that so often provides a stable psychological and spiritual sense of well-being. I am more likely to turn to technology, to connect to people elsewhere and ground myself in a virtual ‘place’. For this reason, I understand why we would turn to robots to comfort us, prefer that technology deal with the messy aspects of human caretaking, and become anesthetized to using our own health as a currency in a quest for rapid technological advancement. But we can and need to do better. Michel Foucault wrote that “Where religions once demanded the sacrifice of bodies, knowledge now calls for experimentation on ourselves, calls us to the sacrifice of the subject of knowledge.” Fear produces collective denial and I am attempting to examine that at a deeper level.

ZJM: Your series Transuranic, employs photography, process, and installation to explore radioactive waste sites. Can you tell me more about the series (this can either take the form of your artist statement, or more loose terms), and how you started it?

AH: In 2013, I was living in Japan and also spent time volunteering in the disaster zone that was left from the 2011 tsunami and nuclear meltdown. Japan and the U.S. have a deeply intertwined nuclear history. Eisenhower’s 1953 Atoms for Peace program helped Japan with the money, training, and propaganda to build their own nuclear industry. Being there was a part of understanding this complex history. I volunteered in Ishinomaki, a place that was once made up of dense forests and homes to 165,000 people. I had seen photographs of Ishinomaki before the tsunami damage and photographs of that forest reminded me of the Pacific Northwest; it felt like home. As a foreign volunteer combating life in a disaster-stricken area, moments where something feels familiar can be intensely comforting. The rich and lucid life that existed in those photographs, however, was now gone. What trees remained, were a haunting shade of purple; long since deceased from the oil and debris that the tsunami carried inland. Black bags, filled with contaminated soil, lined the streets of Ishinomaki for miles. This was what the towns surrounding the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant look like, towns that now only existed in someone else’s photographs and nostalgic memories of home. I left Japan knowing I could return home, but the radiation would never permit many of the Japanese volunteers to.

When I returned to the U.S., I drove from Washington State to New Mexico for graduate school. The route winds through a dense forest along the Columbia River and I thought about that experience of driving through Ishinomaki and having a constant anxiety about the radiation and our safety. Something had changed in me and I became hyper aware of the illusion of safety that I had been permitted for so long, because across this river sat Hanford, a damaged landscape that contains two-thirds of the United State’s nuclear waste. In the distance there were not black bags of contaminated soil, there were 60-year old dry casks of radioactive waste. The route that I was driving on was the Transuranic waste route, where millions of gallons of radioactive waste are transported across our country on, to be buried in New Mexico.

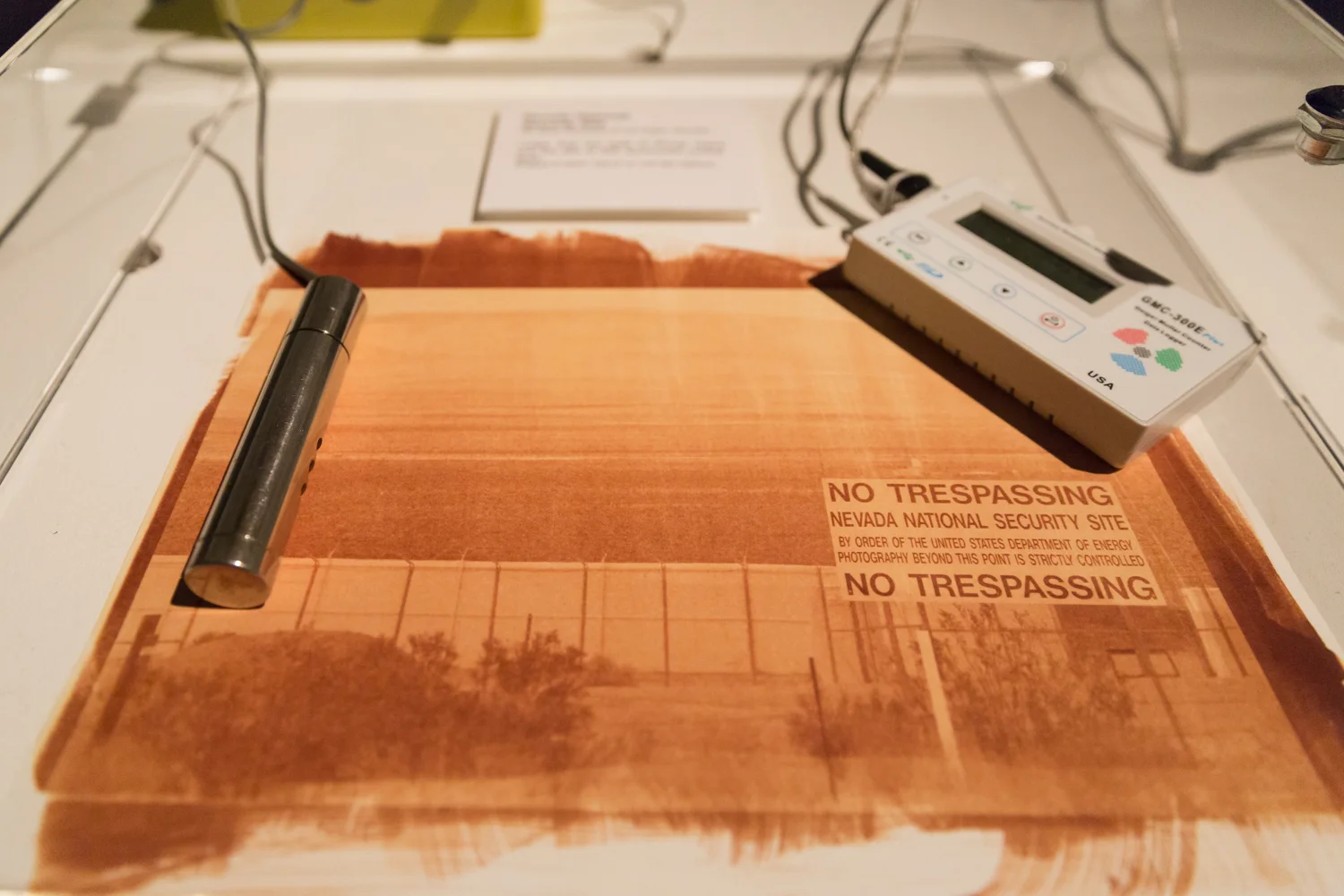

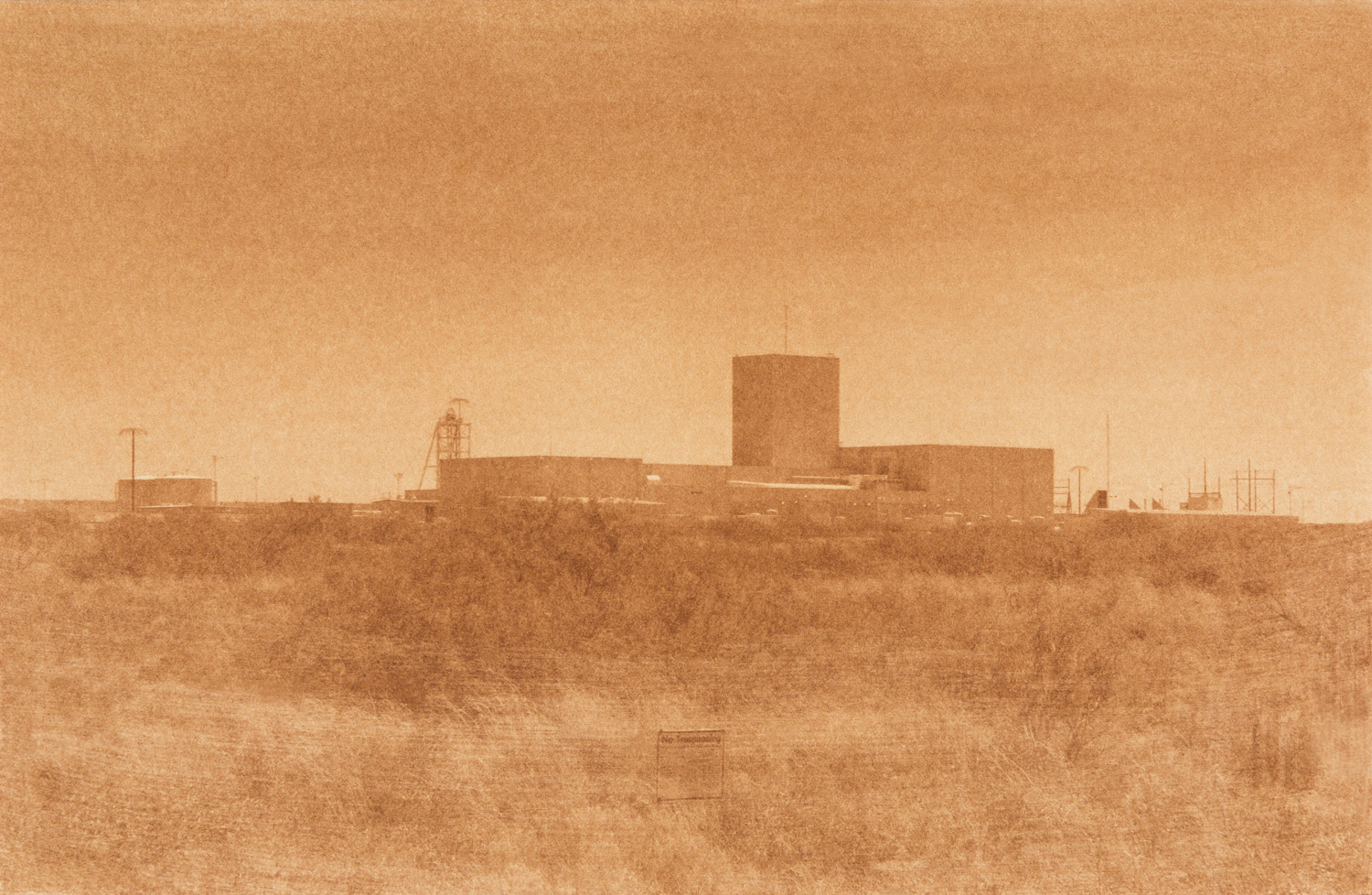

Finding myself in New Mexico and once again in a place with a complex nuclear history, I set out to discover how the nuclear industry was impacting the land around me. In Transuranic, I looked at the citizen’s view of radioactive waste sites and their existence in the banality of everyday life. Radioactive waste is not hidden away in glorious alcoves; it is driven down our highways. It is in our backyard. Sometimes, we catch a glimpse of a sign for one of these sites, which serves as an illusion of containment and transparency. I photographed every site in the Western U.S. that ships radioactive waste to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in Carlsbad, New Mexico, and made them into uranotypes, an archaic photographic process that uses uranium instead of silver. The prints document nuclear facilities from an outsider’s perspective, indicating their ubiquitous and unassuming nature. Their red and yellow hues- formed by the exposure of uranyl nitrate- evokes a haunting nostalgic sensation that is instantly negated by the reality reflected in the images.

ZJM: Last semester, I took a course focused on photography and the landscape. One of the introduction texts we read was D.W. Meining’sTen Versions of the Same Scene. This reading was pretty transformative for me in approaching my own work and how I sww at the landscape. Looking at Transuranic through Meining’s terms, how do you feel you’re approaching the landscape?

AH: Yes, I am familiar with D.W. Meinig’s Ten Versions of the Same Scene, what a great reference to think about in terms of this project! I regard landscape as a complex combination of many of Meinig’s terms. The locations in Transuranic are active habitats, forced artifacts, complex problems, and have been chosen and altered due to a historical view of landscape as wealth. After spending time in cities like Berlin, which advocate for a kind of transparency of history, I tend to investigate the landscape more in terms of ideology and history.

Traveling to all of the transuranic waste route sites was different after volunteering in Japan. Understanding the history of these places, who has sacrificed, and who continues to sacrifice because of them, altered my experience. It felt personal and painful. When I was first researching the rare uranotype process I had a really hard time finding any imagery. When I did find a photo from the late 1800’s, I shared it with one of my fellow Japanese volunteers. She shared it with her grandma, who told me that the color of the uranotype looked like the color of the sky after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. As I stood on the cliffs above Los Alamos National Labs in New Mexico, where that very bomb was made, I remembered that haunting response. I took a photograph of that place of secrecy that had brought about so much destruction… and I gave the sky the color of the bomb.

ZJM: The work in Transuranic also uses installation in the form of geiger counters. I see the photographs as documents of this intervention placed in the landscape by the government. How do you feel your interventions of these objects play off of that?

AH: The photographic images in Transuranic are indexical. I am asking questions, not just about the use and misuse of the nuclear industry, I am asking questions about the use and misuse of photography. How does it speak to truth and illusion? What does it mean to demand that photography be seductive? Grandiose? Otherworldly? Some of my work deals with fictional narratives inspired by truth but here I felt the weight of responsibility to tread very carefully with what I made. The truth was far more frightening than any fiction. I asked myself: What is at risk if I create beauty from toxicity, in the framework that we exist at a distance from it? The photographs needed to be quite and simultaneously threatening.

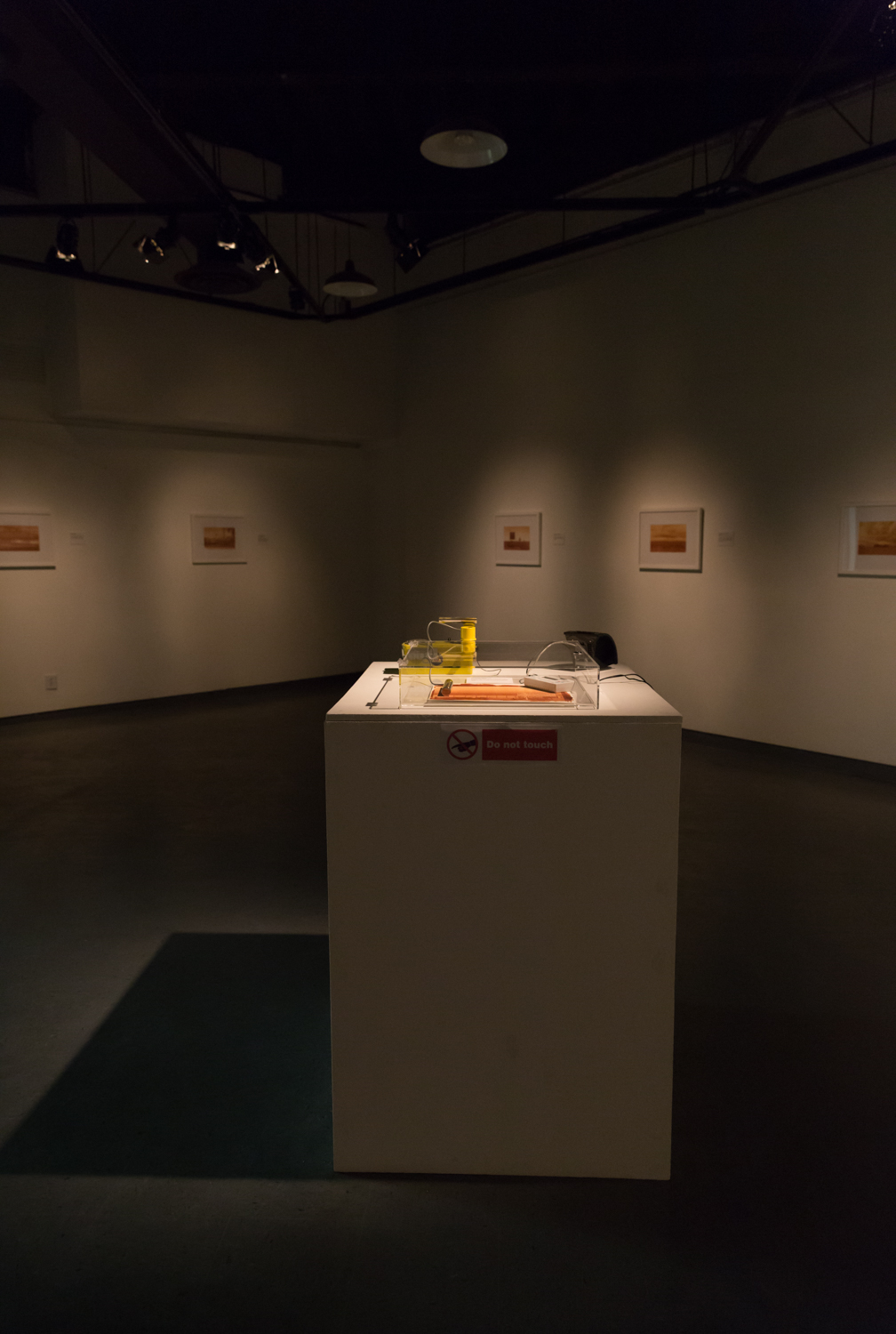

The installation experience is essential in Transuranic. Two Geiger counters, a cold-war era analog model and a digital consumer model, sit on a uranotype print in the center of the room and send out an auditory reading in clicks, based on the amount of radiation present in the print. By creating the prints with the radioactive element uranium and including the Geiger counters, I reveal the toxicity of these seemingly banal places. The viewer enters a dimly lit room and views each of the thirteen prints while the Geiger counters send out a constant warning: click-click-click.

Transuranic is meant to provoke the viewer. To use materials that transgress the social demarcation of borders and boundaries, to attempt to quantify just how much radioactive waste we live amongst, and to reveal places that have been rendered permanent sacrifice zones, serving as a reminder that all nuclear issues are global issues.

ZJM: Let’s switch gears from making your own work, and how you use photography to connect with others. In 2016 you founded the Creative Advocacy organization. Can you talk about this project – how it started, its goals, and where you see it headed?

AH: When I finished my undergraduate degrees in Utah, I was lucky enough to receive a grant to do a Creative Capital workshop. I learned to recognize and value the skills that I had as an artist and entrepreneur. I owned my own business for a few years before going to graduate school, where I also studied Arts Management and worked in grant writing. These experiences made me interested in teaching professional development skills and advocating for artists. I teach community workshops through Creative Advocacy, as well as offering individual mentoring sessions. So far, Creative Advocacy has been a means of linking people together and providing artists with resources but I have also been involved in collecting interviews from artists who are making challenging and inspiring work.

There are lots of projects in the future for Creative Advocacy, including exhibition involvement and grants for artists. It’s a slow growth though; right now I am focused on leadership roles in a few different arts organizations including the College Art Association and the Society for Photographic Education. Volunteering my time with arts organizations during this political climate serves as a reminder of how great our art community is and it keeps me from getting too cynical.

ZJM: As I student and educator, I often feel that the classroom can be a fairly limited space in providing broader connections to others in the field outside of individuals you may have personal connections to. How do you feel that programs like Creative Advocacy can help bridge these gaps?

AH:There are a lot of great organizations that provide very specific advice or feedback to artists or small creative businesses but they don’t necessarily offer the tools or practical advice that someone might be seeking. Networking and being involved in community groups is a great way to stay involved in one’s field. Mentorship is another way to gain knowledge and is important at many stages of one’s career. I think it’s important to teach students that they have to be continually learning and advocating for themselves.

ZJM: What’s next for you, Abbey?

AH: This summer I have been working as a technical editor and reviewing a fantastic photography textbook. I am also working on publishing a paper that I presented at the National Society for Photographic Education this past spring titled, Insider/Outsider: Photographing The Other. I have some collaborative projects on the horizon but right now I am looking forward to the rest of my summer with the newest edition of our family: an adorable, rambunctious puppy named Kyoto.

ZJM: Thank you again for speaking with me.

AH: Thank you so much Zora! What a pleasure!

All images © Abbey Hepner