Q&A: Lauren Kelly

By Hamidah Glasgow | March 27, 2017

Lauren Kelly, garnered First Place in the Lensratch Student Prize Exhibition for her project, Echoes – Growing Up With PTSD: A consequence of Juvenile Rape.

Lauren Kelly’s project, Echoes – Growing Up With PTSD: A consequence of Juvenile Rape is powerful in its revelatory subject matter, but also in the brilliance of its narrative and visual interpretations. I viewed this project having seen the recent documentary, The Hunting Ground, and having read John Krakauer’s Missoula, so this subject was much on my mind–as a woman, I am hyper aware of the global travesty of sexual assault. Lauren’s project shed new light on an important subject, which was rooted in the personal, yet universal in the articulation of the work. It is brave, relevant and significant work that hopefully helps bring this subject out of the shadows, removing stigmas and setting victims on a course of healing. Bearing witness, feeling heard and seen, and using art to create change are powerful weapons in this effort. _ Aline Smithson

Originally from the Seattle area, Lauren Kelly is a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design. During her teen years, she developed PTSD from sexual trauma. Exploring her symptoms and recovery from this trauma through photography became an act of catharsis. Self- defined as a “trauma photographer,” L.K. takes an interest in the process of healing — with subjects ranging from landscape to others suffering from the same disorder. Three years after her diagnosis, L.K. now works with and interviews women who also suffer from PTSD due to sexual assault and rape.

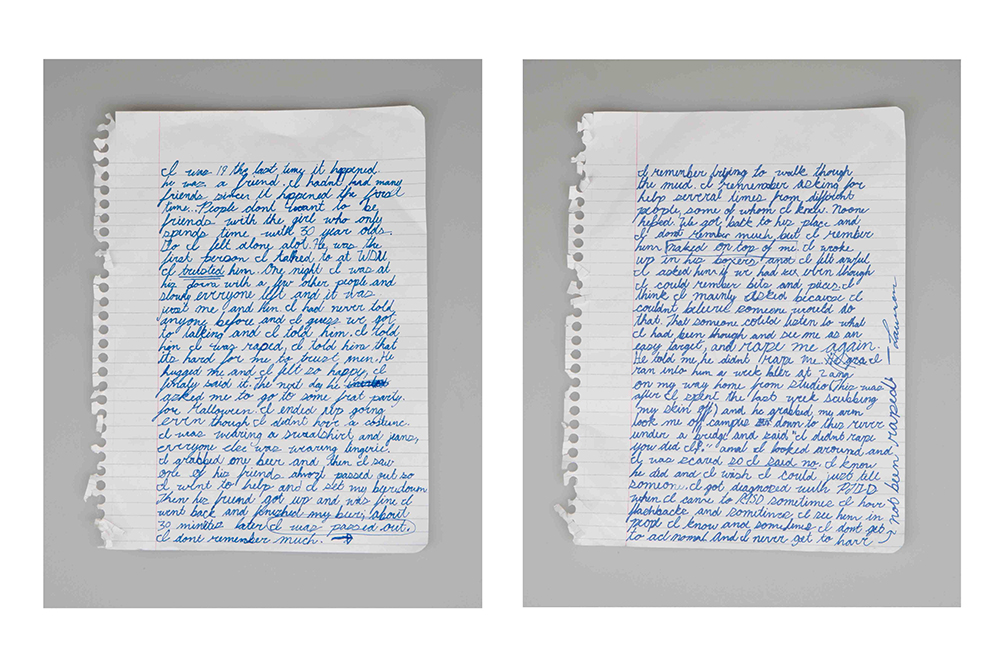

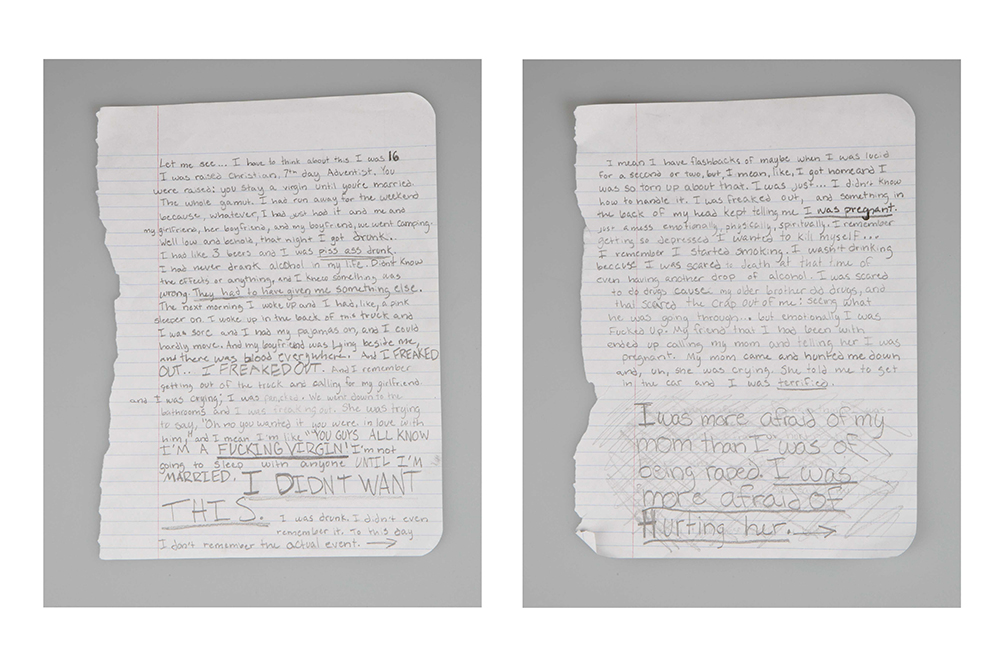

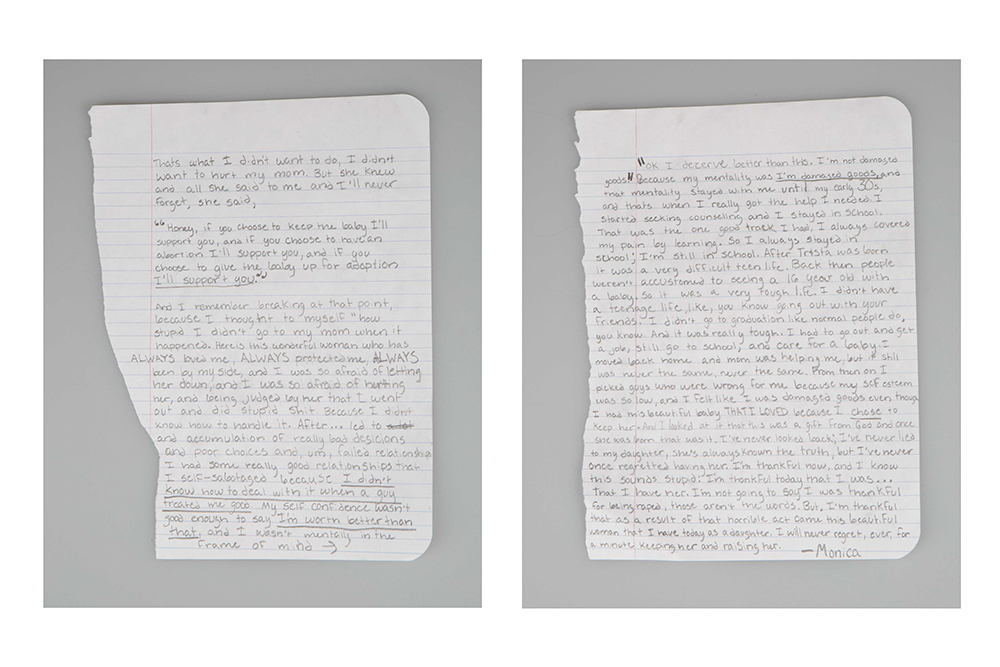

At 14 years old, Lauren was raped for the first time and would not be diagnosed with PTSD for another five years because she felt unable to tell someone. Unfortunately, her story is not an uncommon one. In our society, rape and sexual assault are incredibly common issues. In Lauren Kelly’s series, Echoes – Growing Up With PTSD: A consequence of Juvenile Rape, she conducted interviews with three women who were at varying levels of dealing with their trauma. The images based on these interviews often seem comforting at first, but become colored by the trauma described in the interviews. PTSD affects the part of the brain that allows people to distinguish between past and present memories. Many women experience triggers in places that simply remind them of where their trauma took place, thus creating echoes of memories that exist in no particular space or time. When the viewer interacts with the images through the interviews, they become witness to these stories as a close family member or friend would be. Through encouraging more people to be active witnesses, Lauren hopes to encourage more sufferers of sexual trauma to break their silence as she was able to.

©Lauren Kelly

HG: I admire and deeply respect your bravery and maturity in bringing this personal and traumatic life experience to the public view. How did you come to make the work in the beginning?

LK: I was 19, and I had just been diagnosed with PTSD, and I wasn’t entirely sure what that meant. I began making the work because I needed to understand if I could heal from this. I needed to talk to other women who had been through this before me. The first women I talked to were introduced to me by a friend of mine. After making the initial images, I had an easier time finding people who were willing to be interviewed.

HG: Your images are moving and elude not only to your trauma but so many other women who have endured similar experiences. How do we as a country need to change for our current rape culture to shift?

LK: I think there are lots of ways we as a country could do better. As a woman in this country, it isn’t uncommon to grow up being both shamed for your sexuality and placed on a pedestal because of it. I think we could be more open with our kids about sex, so they feel comfortable coming to us when things don’t feel right. We could focus on teaching consent in schools, and I think most importantly we could do a better job of making an effort to listen to the people around us.

HG: Can you speak more to this statement: As a woman in this country, it isn’t uncommon to grow up being both shamed for your sexuality and placed on a pedestal because of it.

LK: For me and, I think, for many other women, we have grown up hearing the words slut, whore, bitch, and more. We grew up going to churches where we were told expressing your sexuality was a sin; we were told to leave the classroom and cover up in school. Meanwhile, we would see women in bikinis on the covers of magazines; on tv, we would see people talk about how we should trim our pubic hair; we were told to be polite and smile at people when they asked. It's really that, as a woman, you grow up feeling like you have to be both a virgin and sexually open at the same time.

HG: Tell me about the clothing and why these images are so powerful? There is a memory that we associate with clothing; these are clearly what remains of the experience along with the memories. What else am I missing?

LK: The clothing is all from actual attacks. I chose to photograph the clothing in a way that was reminiscent of evidence without the harsh light that comes when one is actually photographing evidence. The purpose of this was to show a sort of introspective false evidence. When you are attacked, you tend to look at yourself. What was I doing that made me a target? A lot of women look towards their clothing, and that is where the idea for these photographs came from.

HG: Do women that you work with experience shifting attitudes to going public with their own assaults? If so, what changes through the interviews and images?

LK: It really depends on the person. A lot of the women have come to terms with telling people who are close to them. I think for most people it’s a small, but important change. It’s just realizing there are safe places to share their story.

HG: How has making this work changes your perspective on sexual assault?

LK: I didn’t think it could affect a person for so long after the incident, which is part of the reason why I didn’t seek help for four years after the first time I was raped.

©Lauren Kelly

©Lauren Kelly

HG: What have you been up to with the work since the Lenscratch interview went live?

LK: I have continued to interview women for this project. I have also begun to interview women for a new series I’m working on that deals specifically with sexual assault on college campuses. In addition to the artwork, I’m working towards creating a curriculum to be shared on college campuses that focus on educating the public about the aftermath of sexual assault.

HG: Where do you see the work going in the future?

LK: I would like to be able to show the work in a more public setting with a more structured discussion on sexual abuse. I think it would be amazing to use the work to facilitate discussion within different communities and classrooms.

HG: Thank you for your vision and courage.

All images © Lauren Kelly