Book Review: “Will Harris: You can call me nana”

By Jess T. Dugan | May 4, 2021

Published in February 2021 by Overlapse Books

Hardcover, 7” x 8.5”, 96 pages

Section-sewn binding with paper covers and tip-in; interior tip-ins

120 photographs and illustrations; Afterword text by Will Harris

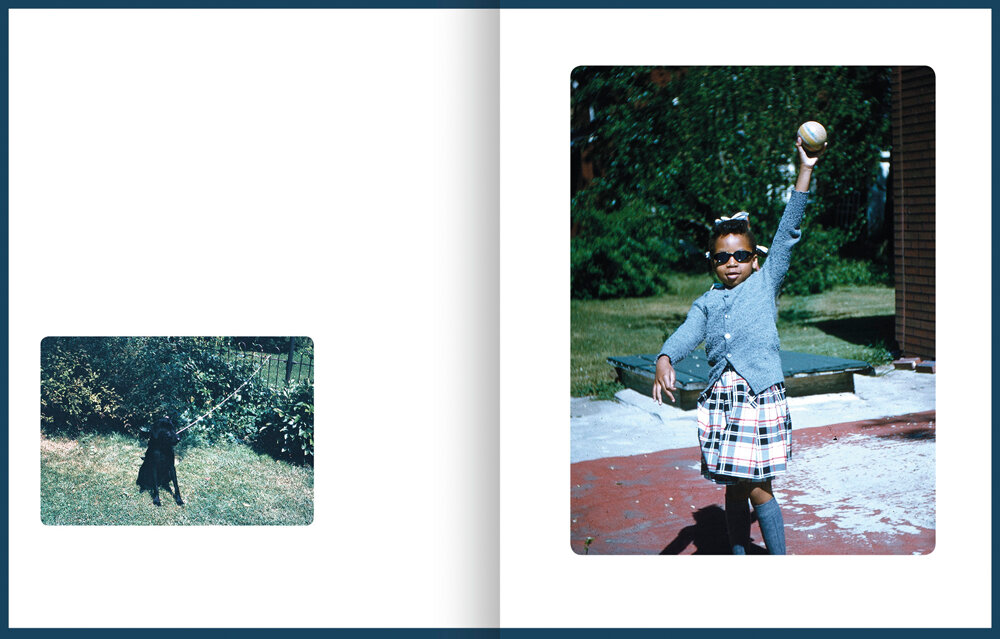

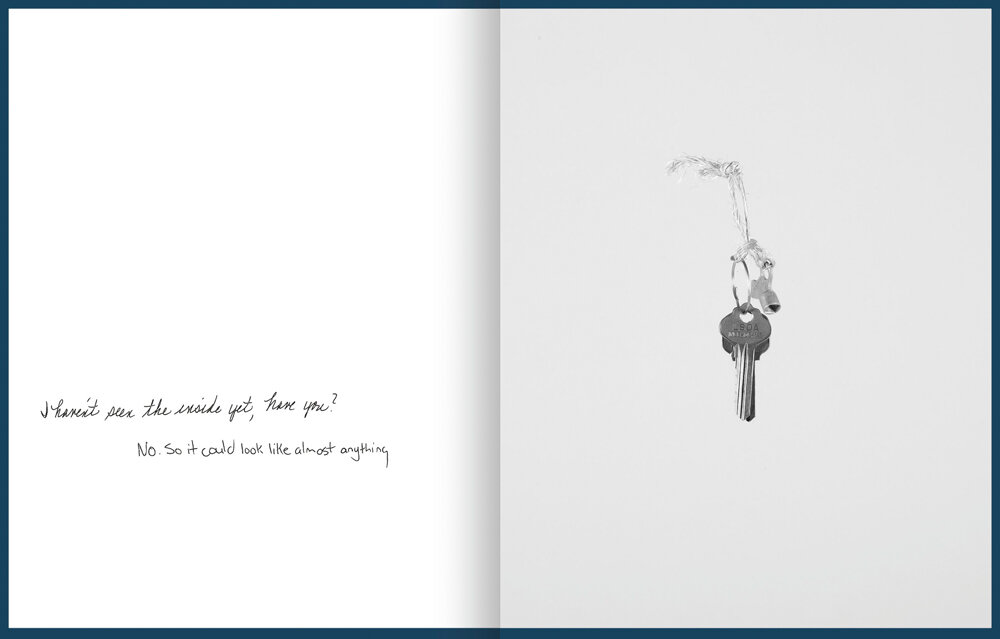

In Will Harris’s new book, You can call me Nana, Harris shares the story of his Nana, Evelyn, who suffered from dementia in the later part of her life. Harris and Evelyn had always been close, but as her memory disappeared, she no longer recognized him as her grandson; instead, he became a friend. Throughout the book, Harris combines archival family photographs, his own contemporary images, tipped in ephemera such as recipes, photographs, and advertisements, snippets of text pulled from recorded conversations with his Nana, and his own reflective writing to create a memoir exploring Evelyn’s struggle with dementia, and her eventual death, alongside his own journey of understanding, grief, and loss. The recorded conversations speak to a desire to remember – Harris made them with an awareness of forthcoming loss – and also to connect, to understand.

The title of the book comes from a poignant, and heartbreaking, exchange between Harris and his Nana:

Did they ever call you Nana?

I’m not Nana, I’m Evelyn.

Ok, is it okay if I call you Nana?

Banana?

No. Just Nana.

Why?

Because. That’s what I’ve always called you. I’ve always called you Nana.

Alright. Nana would be alright.

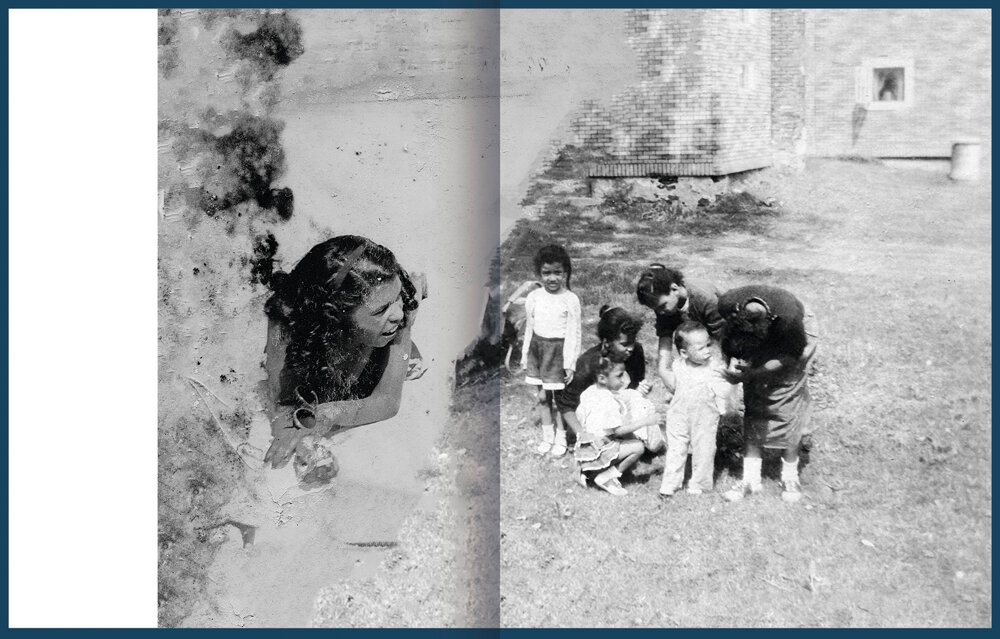

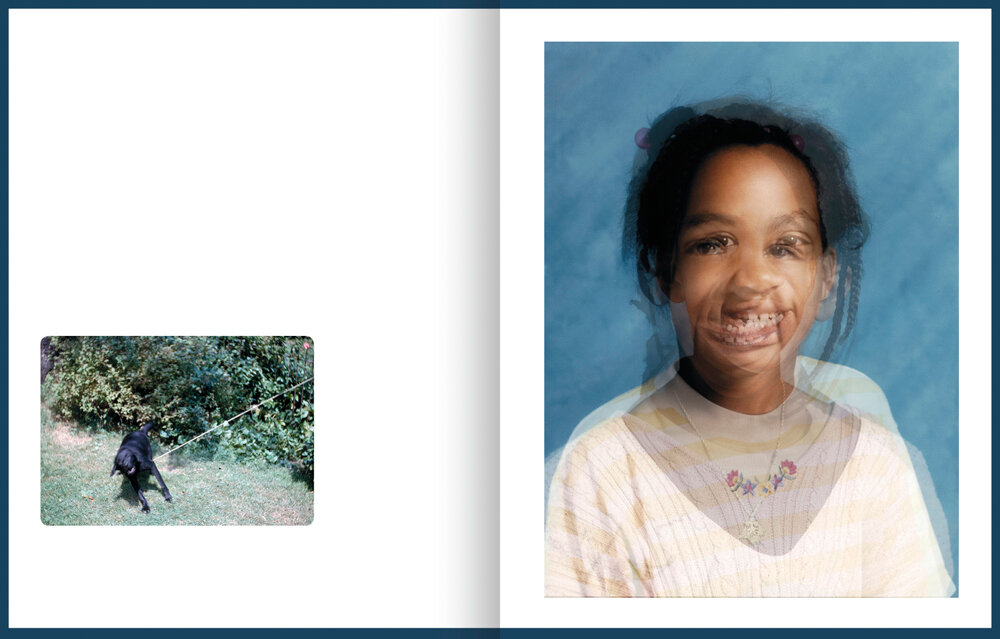

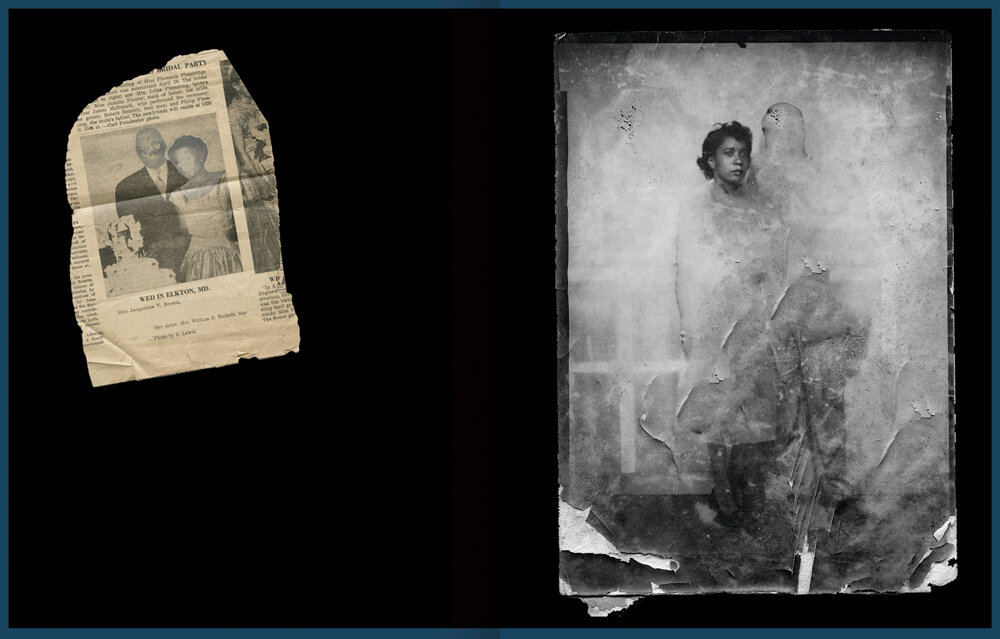

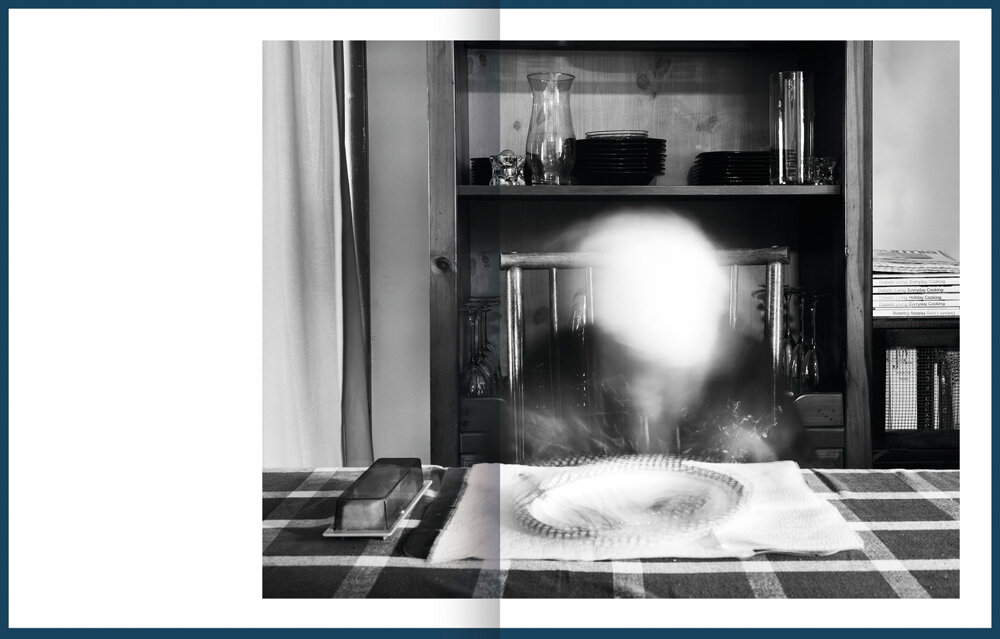

For so many of us, the family photo album is a site we return to over and over throughout our lives, searching for clues. Mining our own personal archives is akin to an archaeological dig; we are trying to understand the past, what happened before us, and how we came to be. Some of the included archival photographs are reproduced in their original form, while others have been altered by the artist’s hand; images are layered upon other images, heads or eyes have been removed, images are purposefully faded or distorted. Several of Harris’s contemporary images are double exposures, utilizing a similar kind of layering to that applied to the older family photographs. Harris gently guides us from the present to the past, layering and interweaving decades of experiences, both those of his Nana and his own. This moving back and forth throughout time is a poetic nod to the experience of dementia, as linear memory disappears and relationships morph into a combination of truth and fiction, of reality and distorted memory.

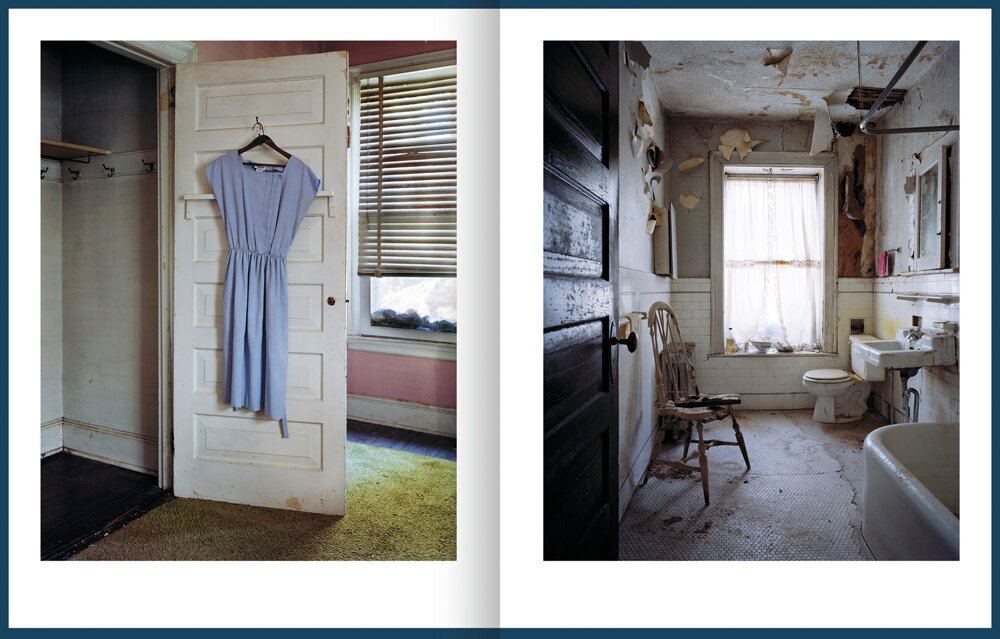

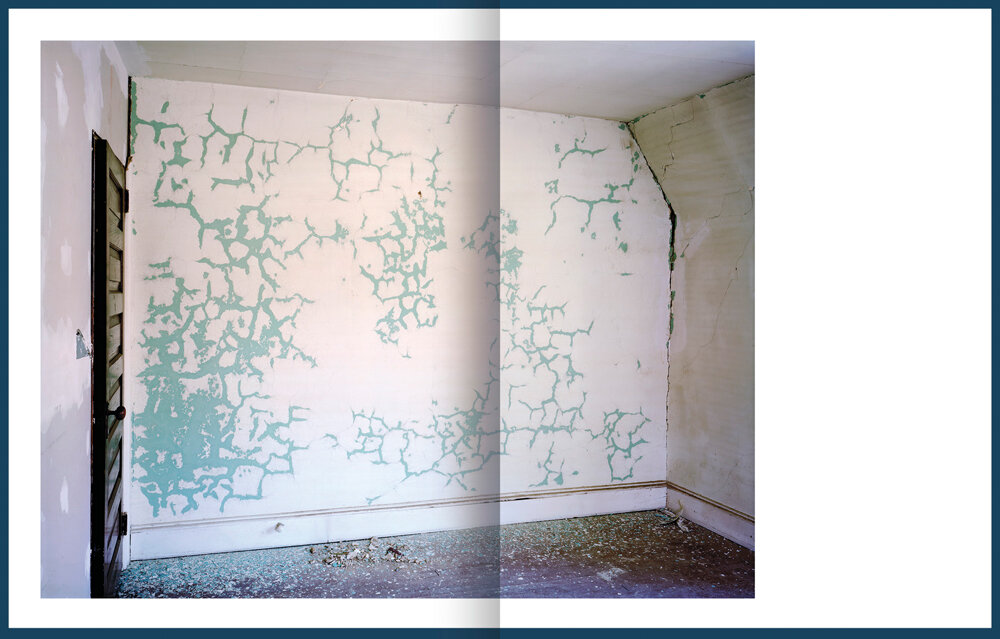

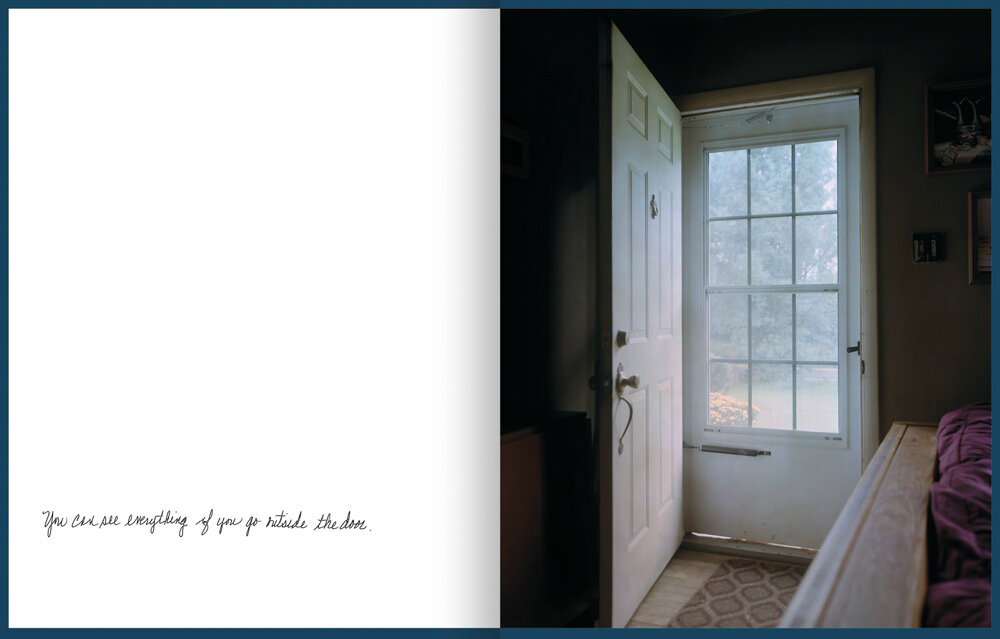

There is also a tracing of place; throughout the book, we see images of Harris’s family home in Pennsylvania, where he now lives, as well as his parents’ home in New Jersey, which was built by his grandparents in 1960. Early in the book, we come across a tipped-in newspaper advertisement for various pre-fab homes advertising a suburban, middle-class existence. Turning the page, we see Harris’s grandfather working on a home under construction, presumably one of the Harris family homes. And still, a few pages later, we see what appears to be a family snapshot of a home, blurry and faded. Home – both as an idea and as a physical place – holds such a powerful position in an individual life and within a family. The idea of home, of finding one’s place in the world, is deeply embedded into this book and into Harris’s process of understanding his own grief and loss.

In the afterward, Harris addresses this grief directly:

It is painful to watch someone die, and I felt like I had to go through that twice with my Nana; first mentally, then physically. I remember hearing stories from her past and now wish I could harness those memories. This work was made as a way to grieve while she was slipping away from me; my attempt to put the pieces together to make sense of it all. The images were made with care, compassion, and love.

You can call me Nana is at once a highly personal memoir and a universal story about family, connection, change, and loss.

You can call me Nana is available from Overlapse Books.