Book Review: “day sleeper” by sam contis

By Kelli Connell | June 1, 2020

Published by MACK in February 2020

Paperback / 7 x 10”

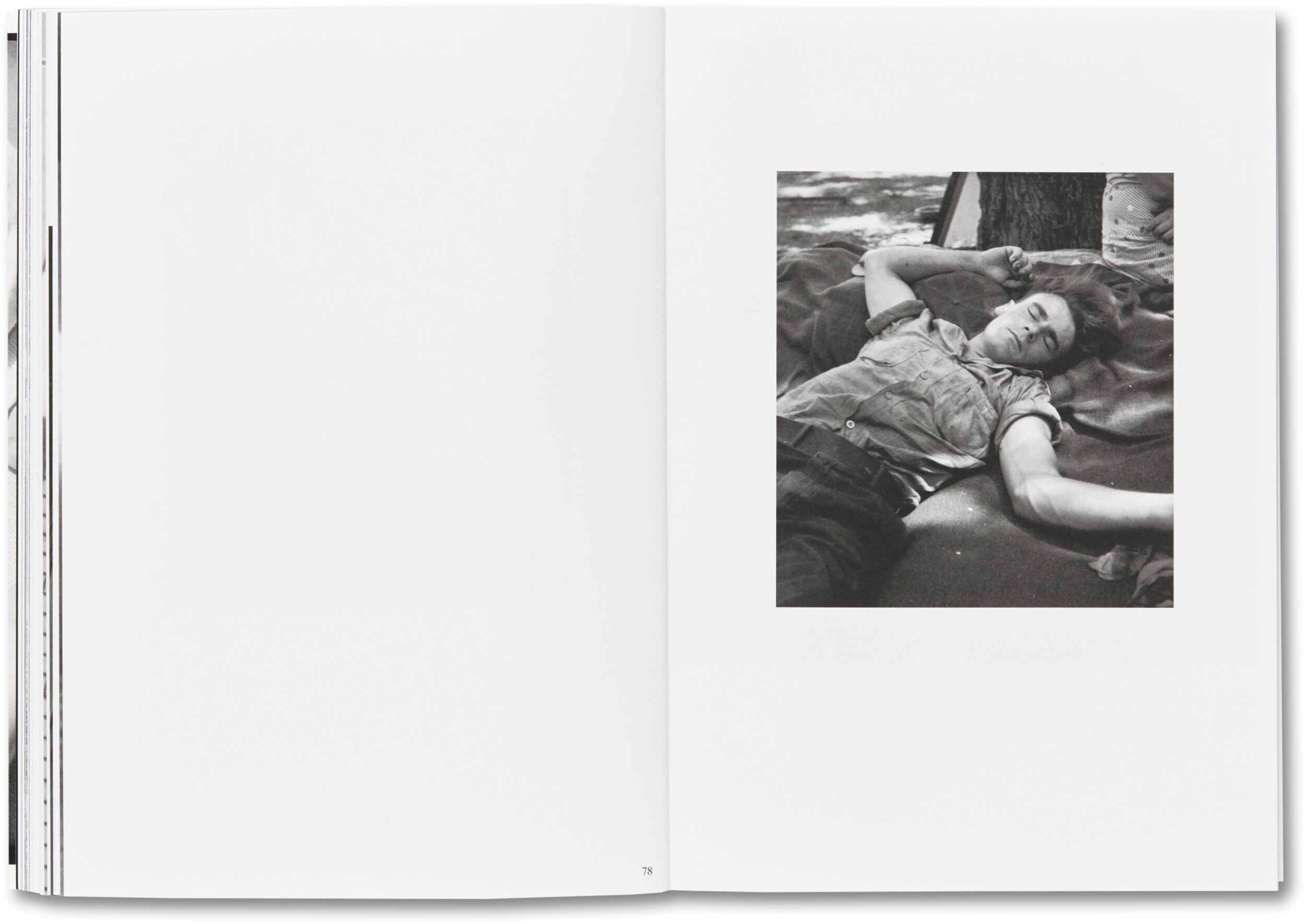

A boy sleeps. A shirt like a turban is pulled over his eyes, a shield to protect from the direct sun overhead. His shoulders and arms are relaxed. His lips are parted. The heat from the sun radiates from his small body. He slumbers in the middle of the day, in between what he was doing and what he’ll do next. In a compelling book of never-before-seen images by Dorothea Lange, edited by Sam Contis, there are seven “day sleepers”, maybe more if we could see the eyes under bowed heads or behind a closed door with a “day sleeper” sign hanging outside.

The idea of the day sleeper is especially relevant during our current pandemic. We wait for work. We hear of injustices and government misgivings and facts spun into fictions. It’s all overwhelming. Those who absolutely have to go to work go. And those of us in another limbo do what we can, some of the time, but mostly bow our heads, shut our eyes, enjoy the heat on our skin, the soft breeze curling about, or the flowers as they break through the dirt, bloom, burst and fade.

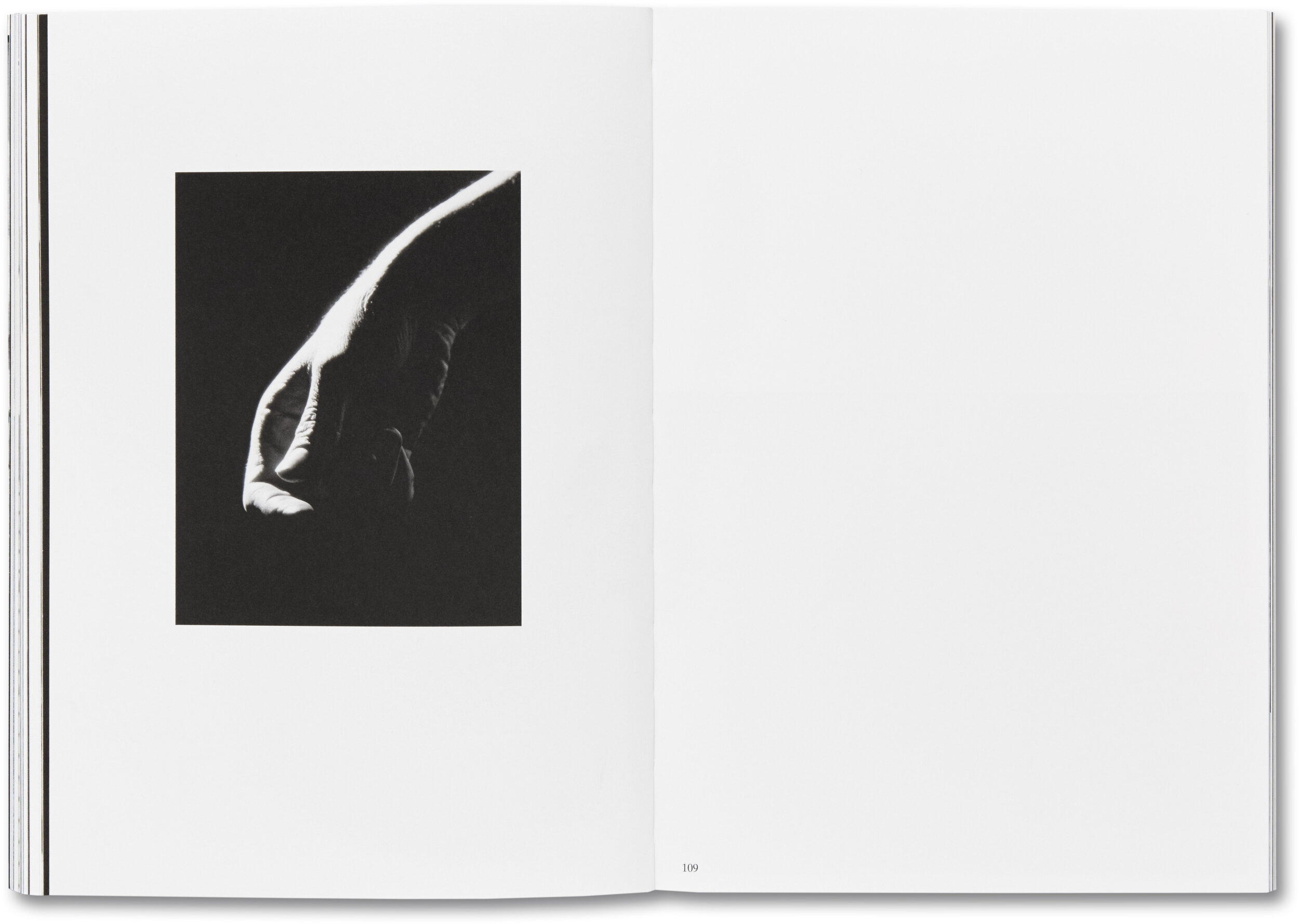

In Day Sleeper, each picture unfolds into the next. The size of images – and their careful pacing – creates a cadence. Seeing such a variety of images, both in subject matter and treatment of scale, creates an awareness of how things might be different. It seems as if the possibilities are endless. The images themselves could be reinterpreted in many ways depending on those chosen and the context built around them through the act of editing.

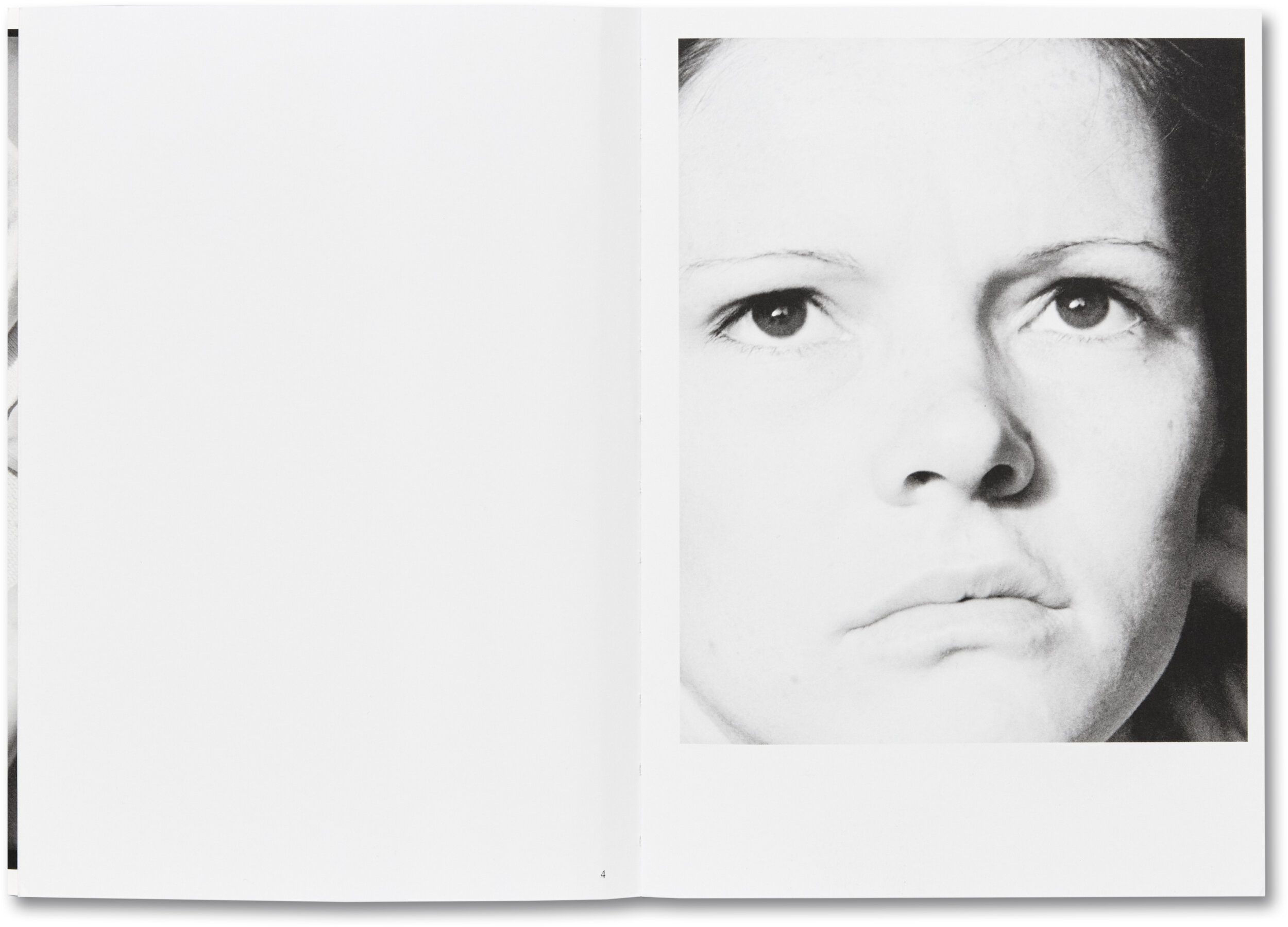

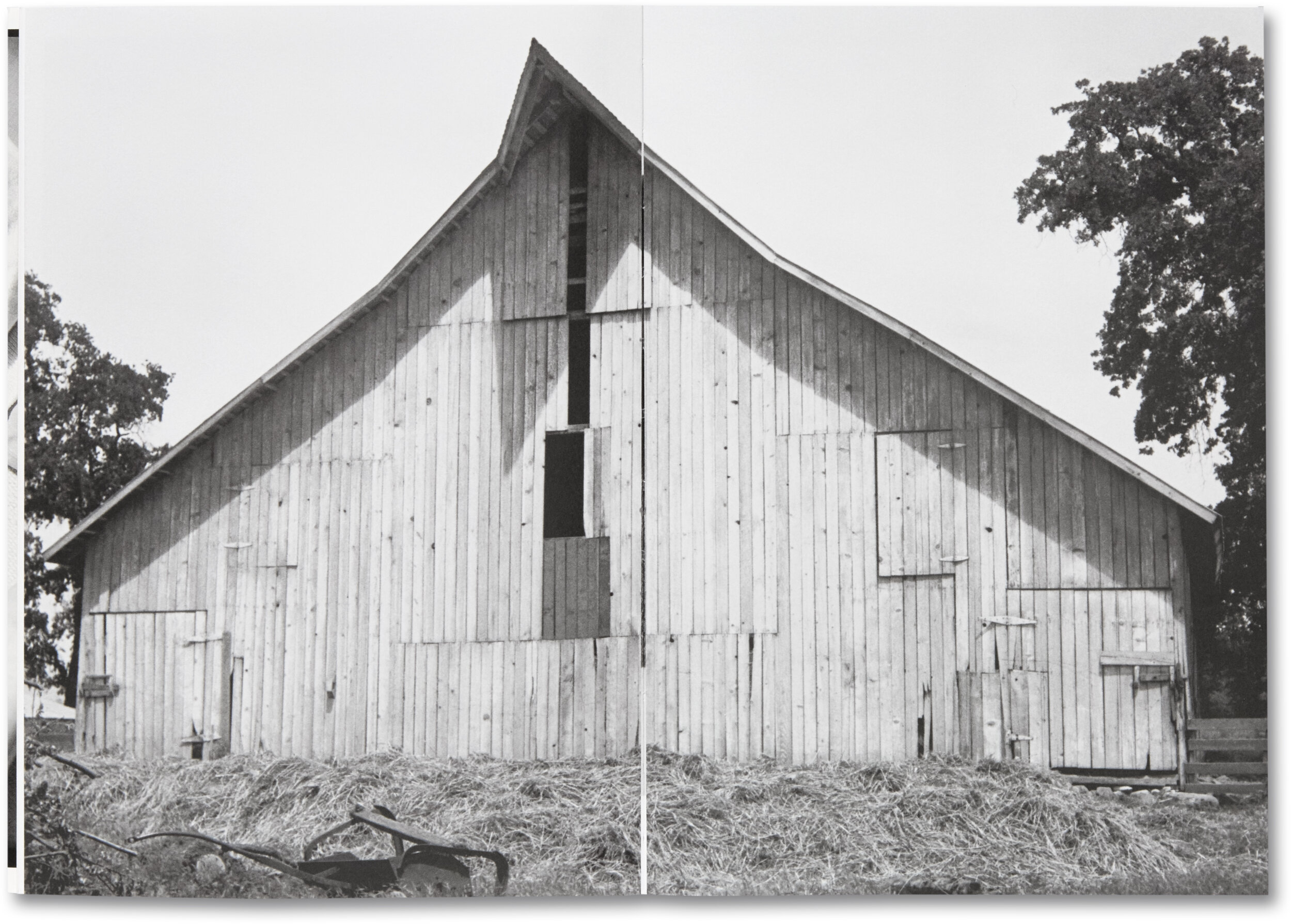

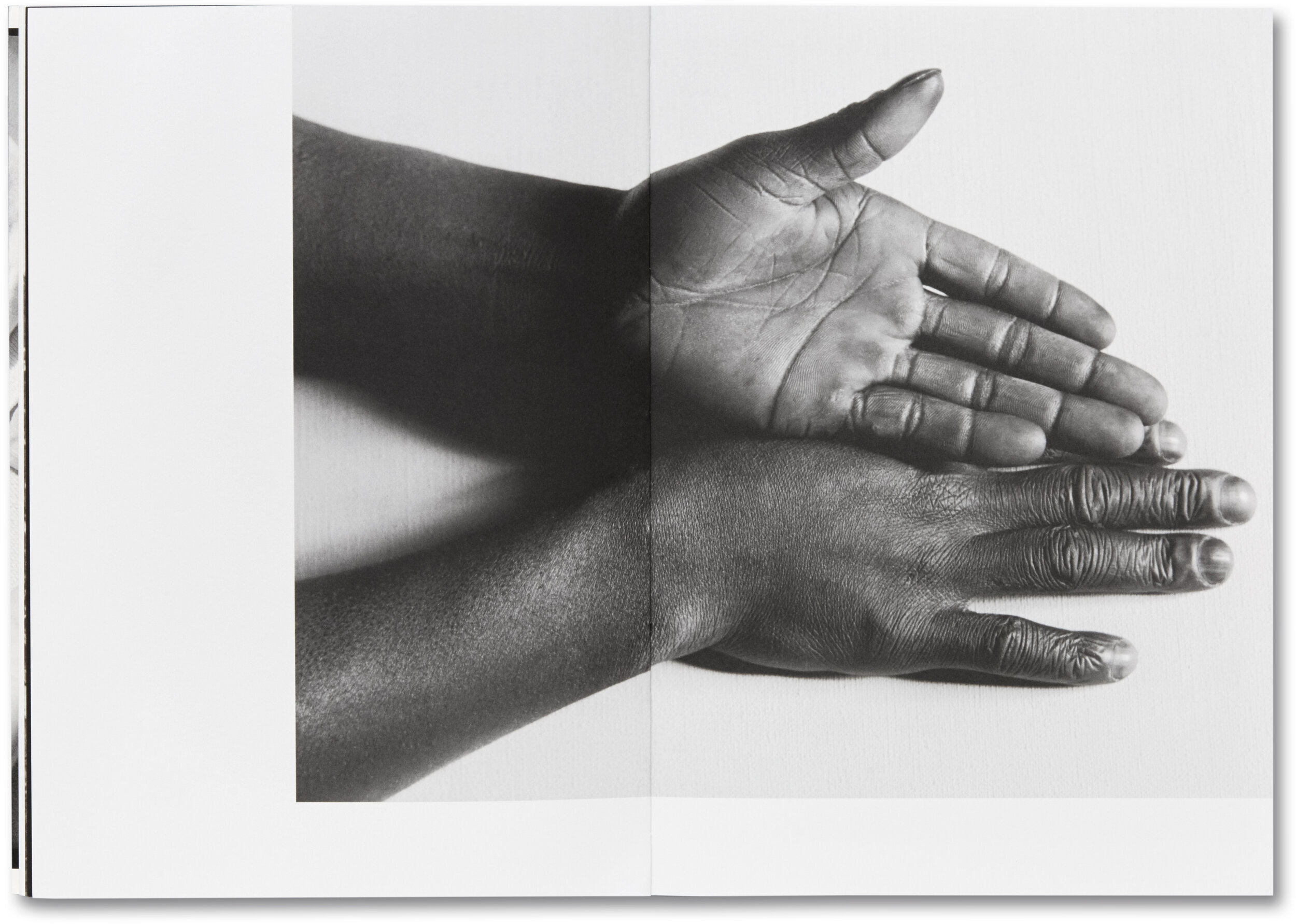

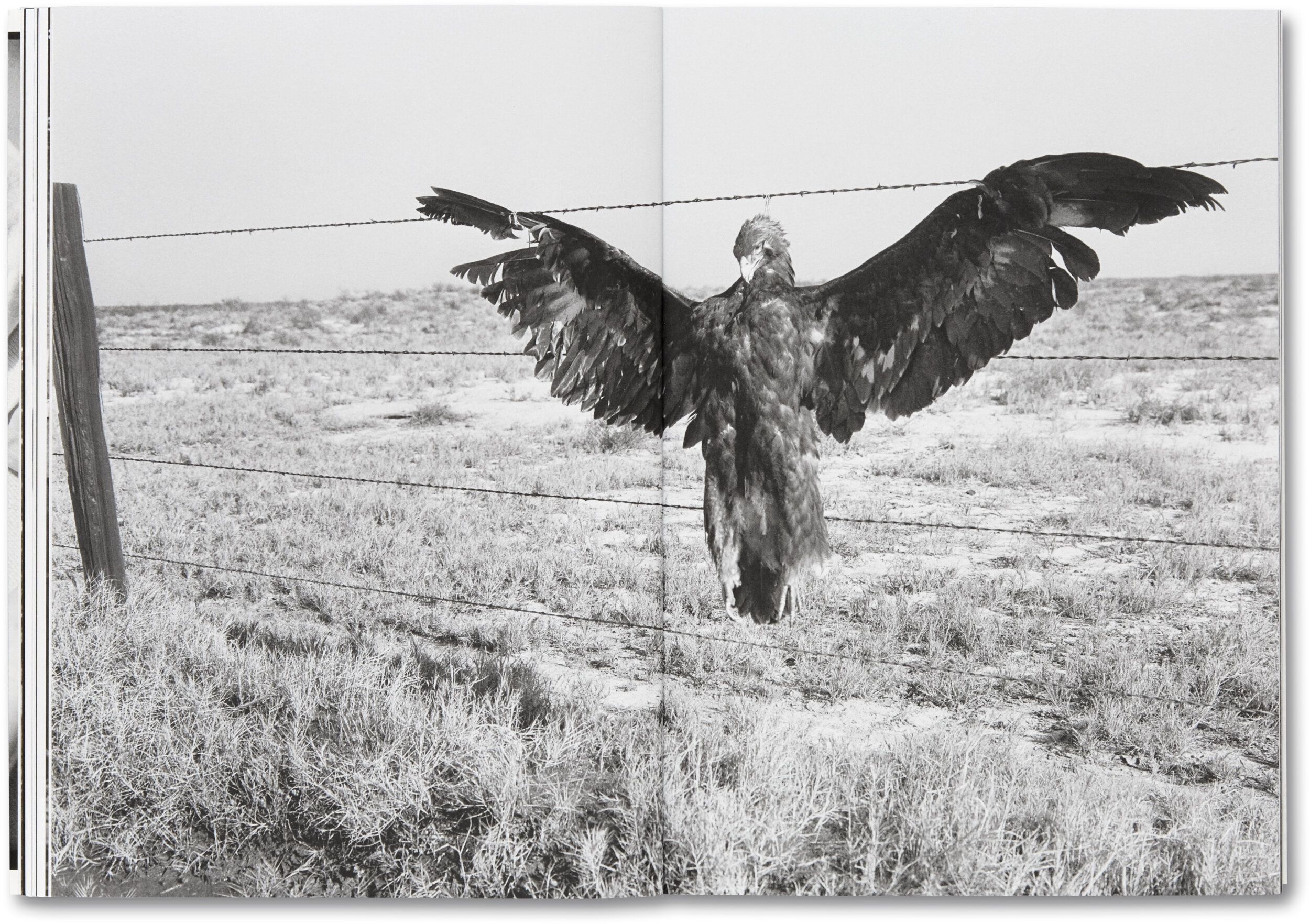

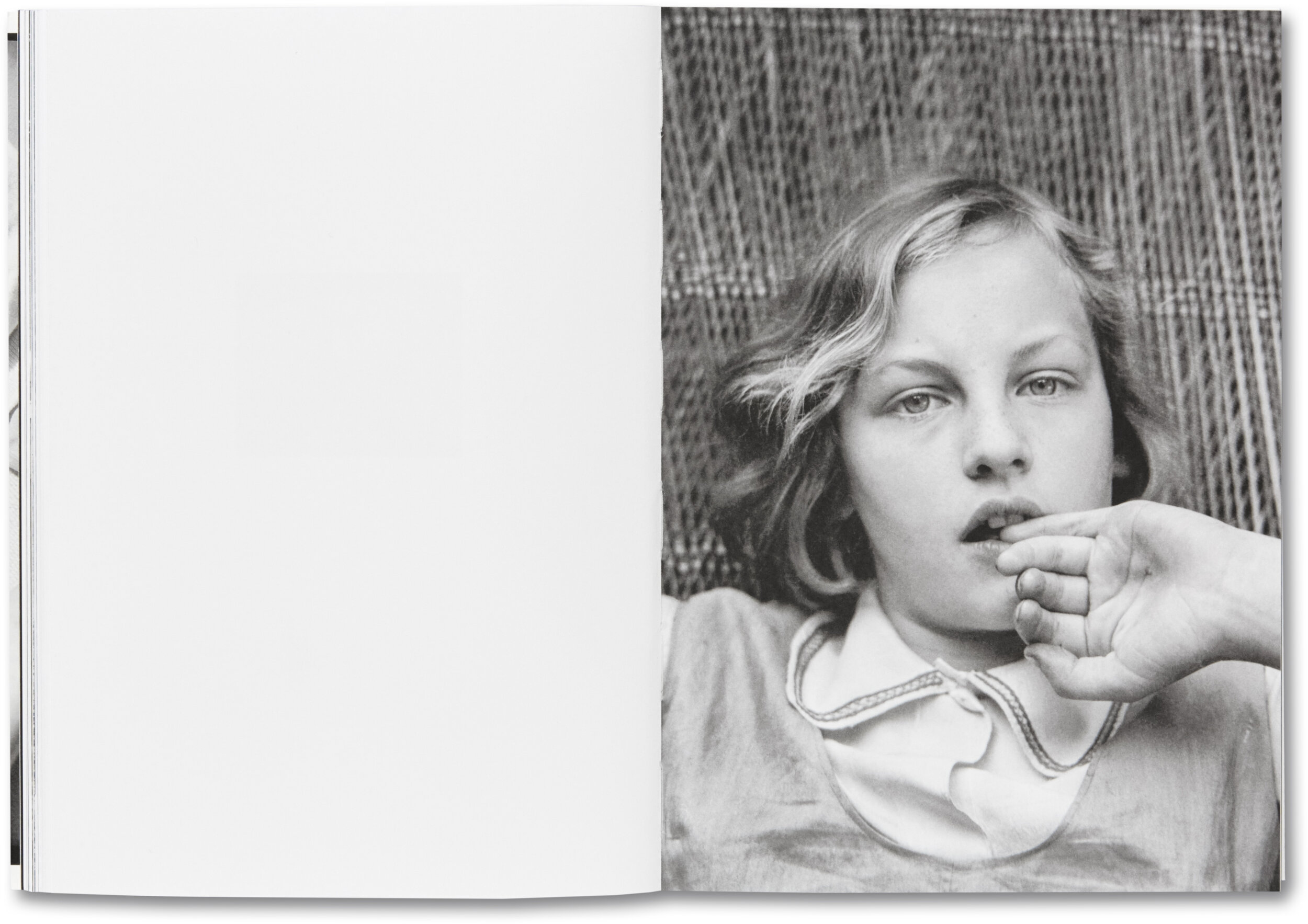

Contis’s edit is dreamlike: the somewhat disparate images reflect many aspects of Lange’s life. We see images of her son and first husband at leisure; images taken on assignment for the Farm Security Administration; work made documenting the U.S. Government’s imprisonment of Japanese Americans; portraits made in her studio in San Francisco; photographs made in her free time on the streets of men and women walking to work or taking a break; and images of nature, two trees intertwined in the garden she and Paul Taylor shared in later years. These images, woven together with no titles, dates, or language, create an almost indistinguishable web that gives no hierarchy between images made during a certain time, for a particular job, or at leisure. All of the images create equal parts of a whole, a symphony or choreography for a life. In the back of Day Sleeper, Contis shares a quote from Lange, “I would like to be able to photograph constantly, every hour, every conscious hour, and assemble a record of everything to which I have a direct response. I would like to accumulate a file of images which would be a complete visual diary.” It seems to me that Contis let this quote lead her edit of the book, one that feels like flashes of memories from – perhaps – Lange’s psyche.

Contis’s edit gives a fuller picture of Lange than we have ever been afforded due to how Lange’s work has been contextualized and written about, affirming the views we are aware of: that Lange was one of the influential photographers working for the Farm Security Administration during the 1930s who lead the way for a more documentary style of picture making, and most importantly, that she was the photographer who made the iconic Migrant Mother image during the Great Depression. Yet, what do we miss when we summarize someone’s career into a few paragraphs accompanied by a mere handful of images? What is important in Day Sleeper is that Lange’s work was seen by another photographer, a woman, who felt, decades later, a shared camaraderie, a communion, as she unearthed images from an archive to reveal another view, another layer of someone, which is perhaps a fuller story to tell.

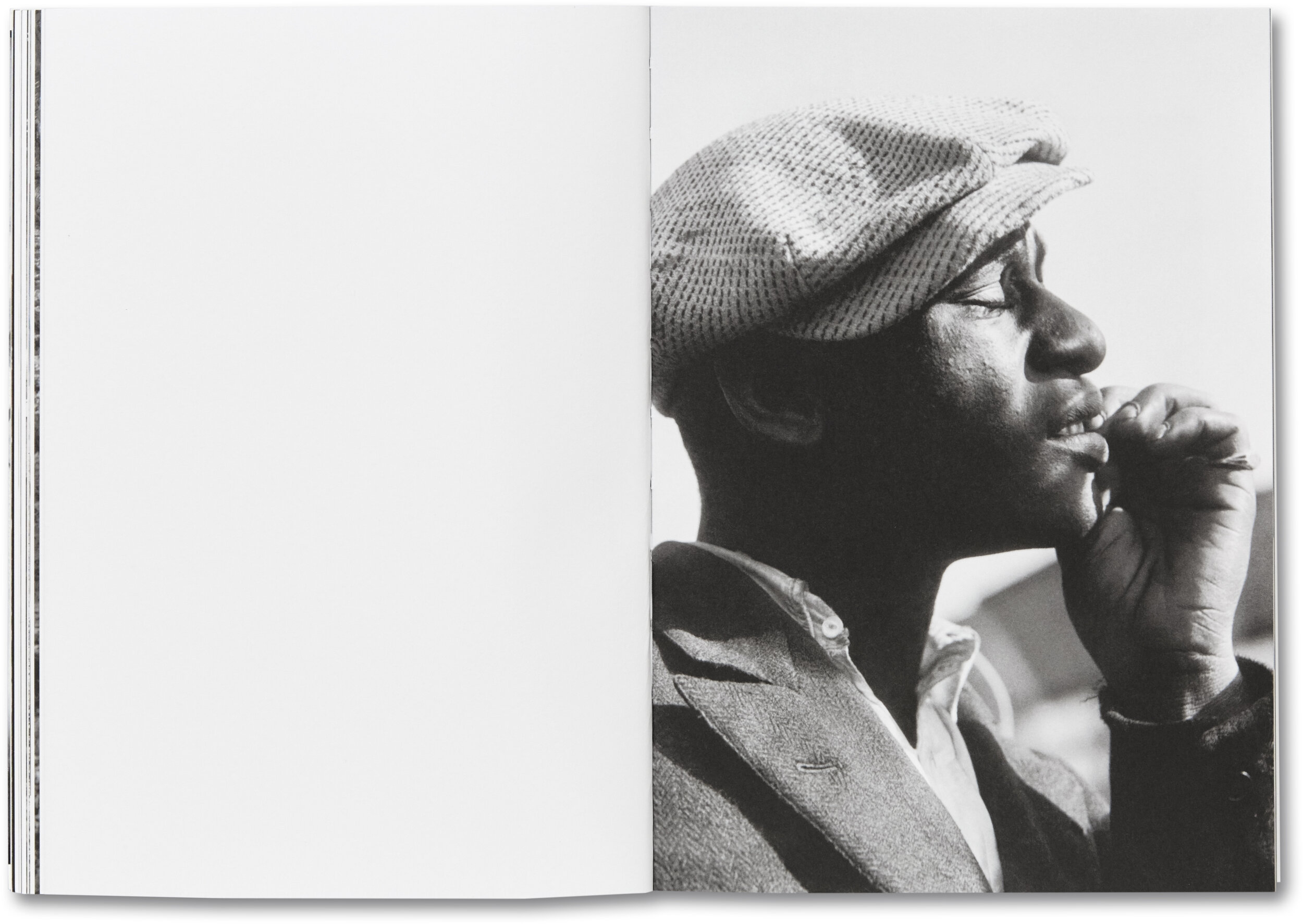

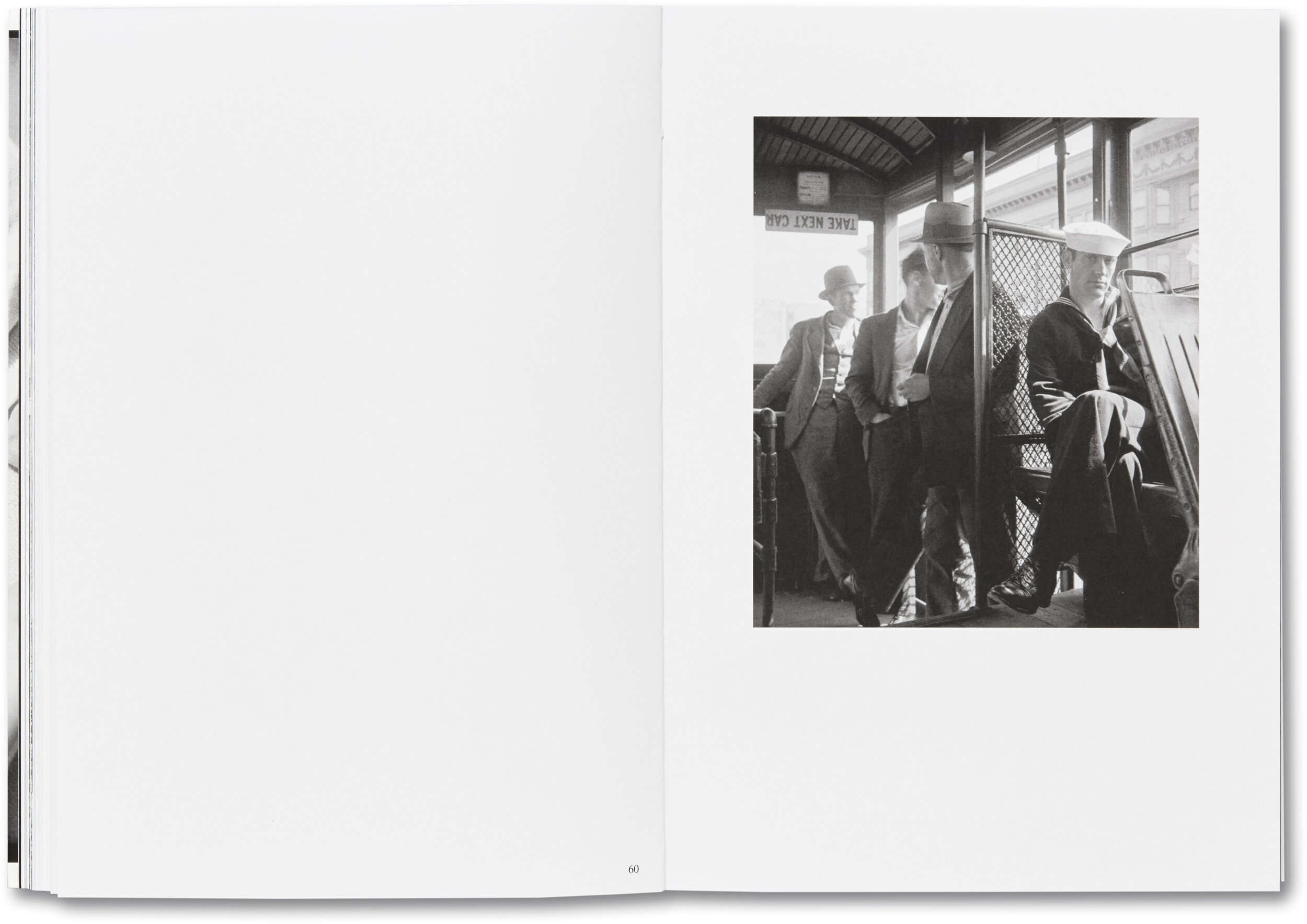

And yet how complicated life must have been then. The promise of the new modern woman at the turn of the century created hope for a new role in life, one of freedom and agency and independence. New definitions of woman, matriarch and mother were on the tip of the tongue, but then again, so was the difficulty of accepting them when society was not quite ready to offer support. The Depression came and affected everyone: women and men, young, old, wealthy, poor, all races, all geographic locations. Social injustices were endured by many during the Depression and World War II. And Lange was there to respond. To capture the rhythm of life in its intensity, its beauty, its death, with its fleeting moments of hope: a gaze on a bus held long and knowing; the gentle touch of arms around the shoulders of men in a crowd; the sun on the lids of a beautiful man’s closed eyes; all punctuation to a tired, hot, and slow life weighed down by the times. It’s so hard, yet beauty is there: the tide rolls in, a tree provides shade for a day sleeper, clean laundry flaps in the wind.

In Susan Sontag’s essay Against Interpretation she argues, “Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art….What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.” Sam Contis’s edit of Dorothea Lange’s images does just this.

Day Sleeper by Dorothea Lange and Sam Contis is available from MACK. A related exhibition curated by Sarah Meister entitled Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures is on view at MoMA (virtually for the time being). The exhibition includes three Lange photogravures selected by Contis.

All images are spreads from Day Sleeper (2020) by Dorothea Lange and Sam Contis, courtesy of MACK.