Book Review: “It’s raining… I love you” by Molly Landreth & Jenny Riffle

By Rafael Soldi | September 9, 2021

Published by Minor Matters

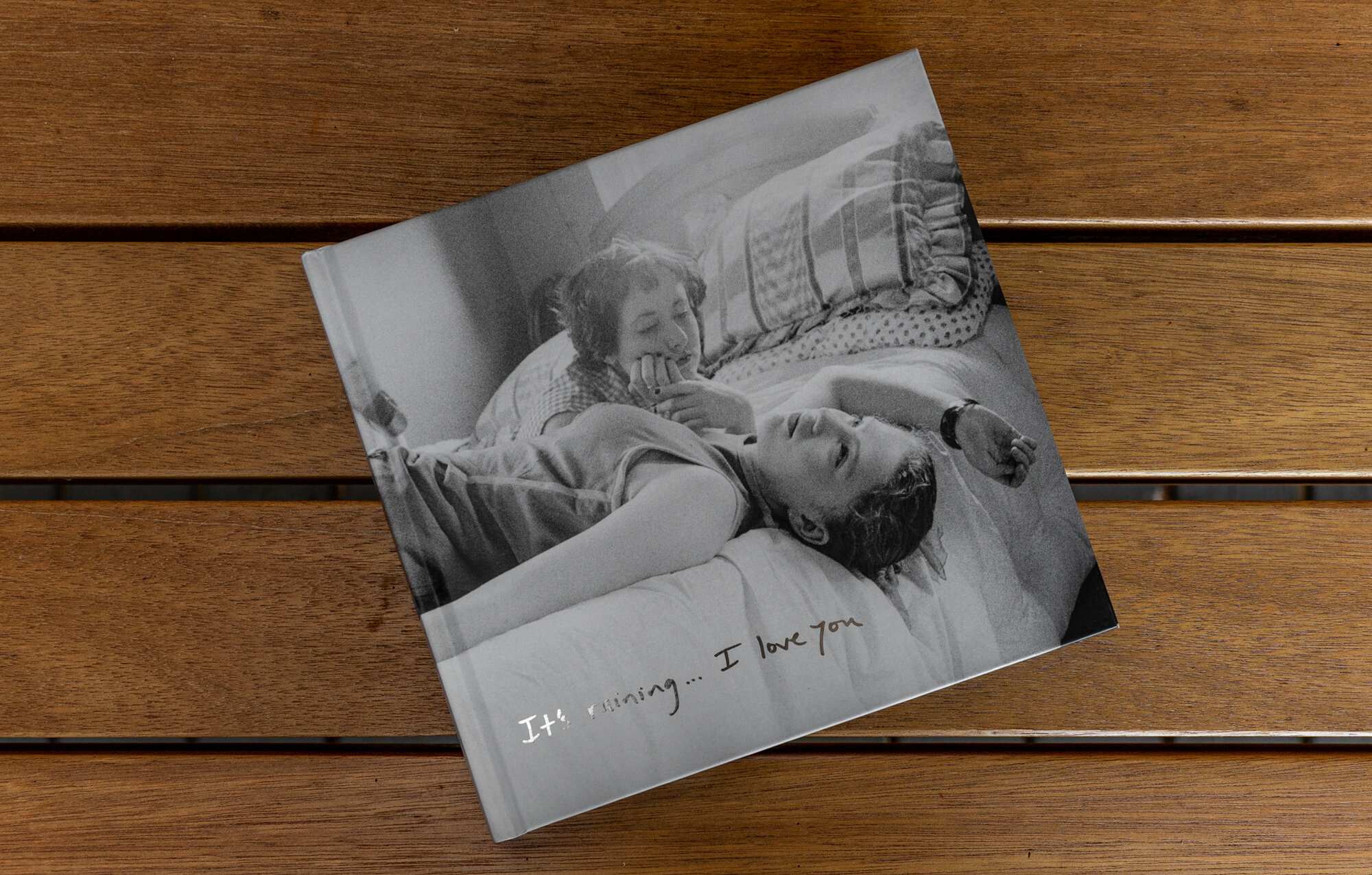

8 x 9.5 horizontal, hardcover; ~50 black and white and 40 color images; 128 pages

With an essay by "Boys of Alabama" author Genevieve Hudson

“It’s raining… I love you,” published by Minor Matters, brings together an archive of collaborative photographs, letters, and ephemera drawn from the summer of 1999, when Jenny Riffle and Molly Landreth, home from their first year at separate colleges, documented the precious and banal moments of early adulthood. Presented along with selected correspondence from the remainder of their college years, the photographs are a testament to the power of enduring friendship, and the creative spirits of two unique yet complementary photographers.

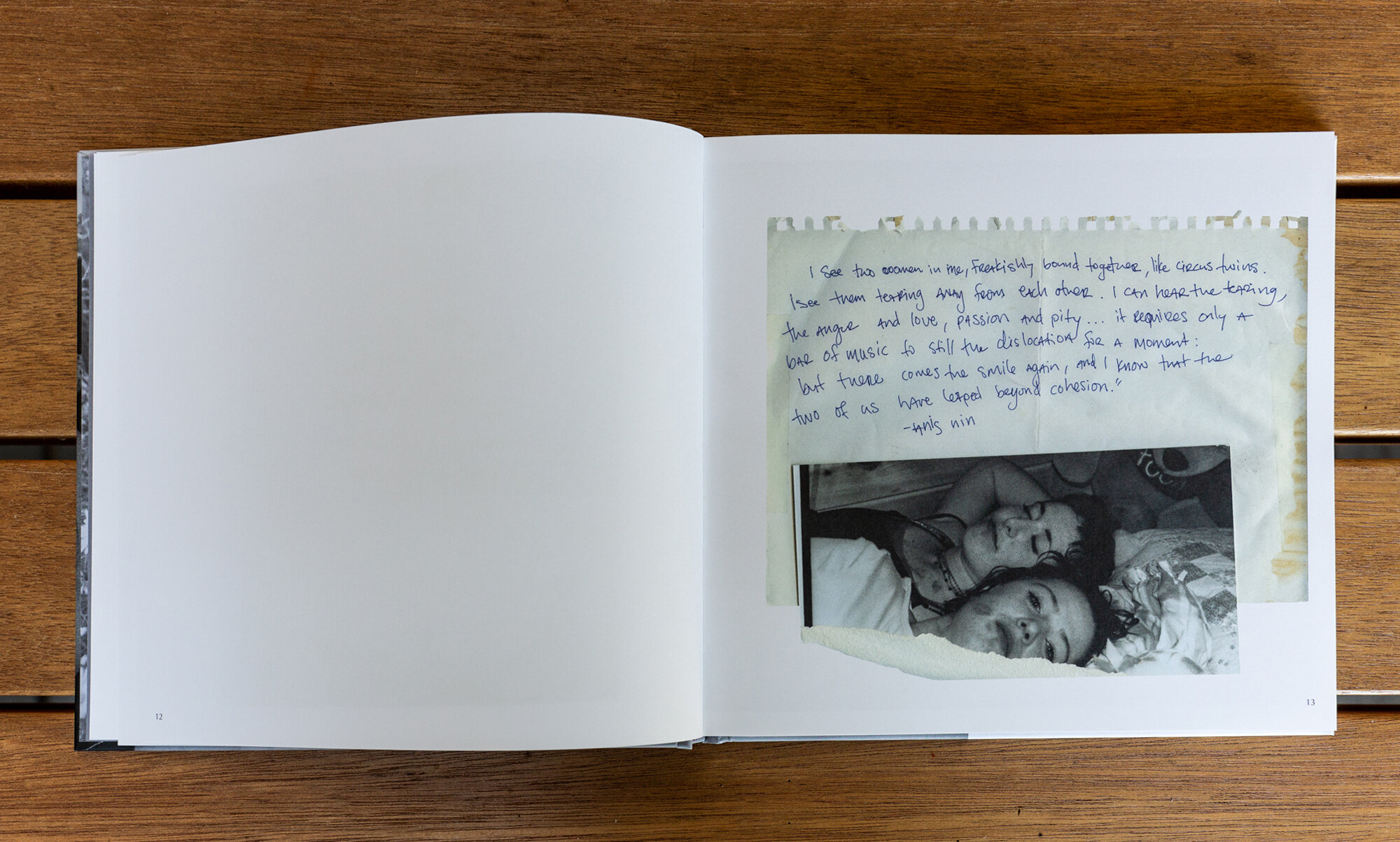

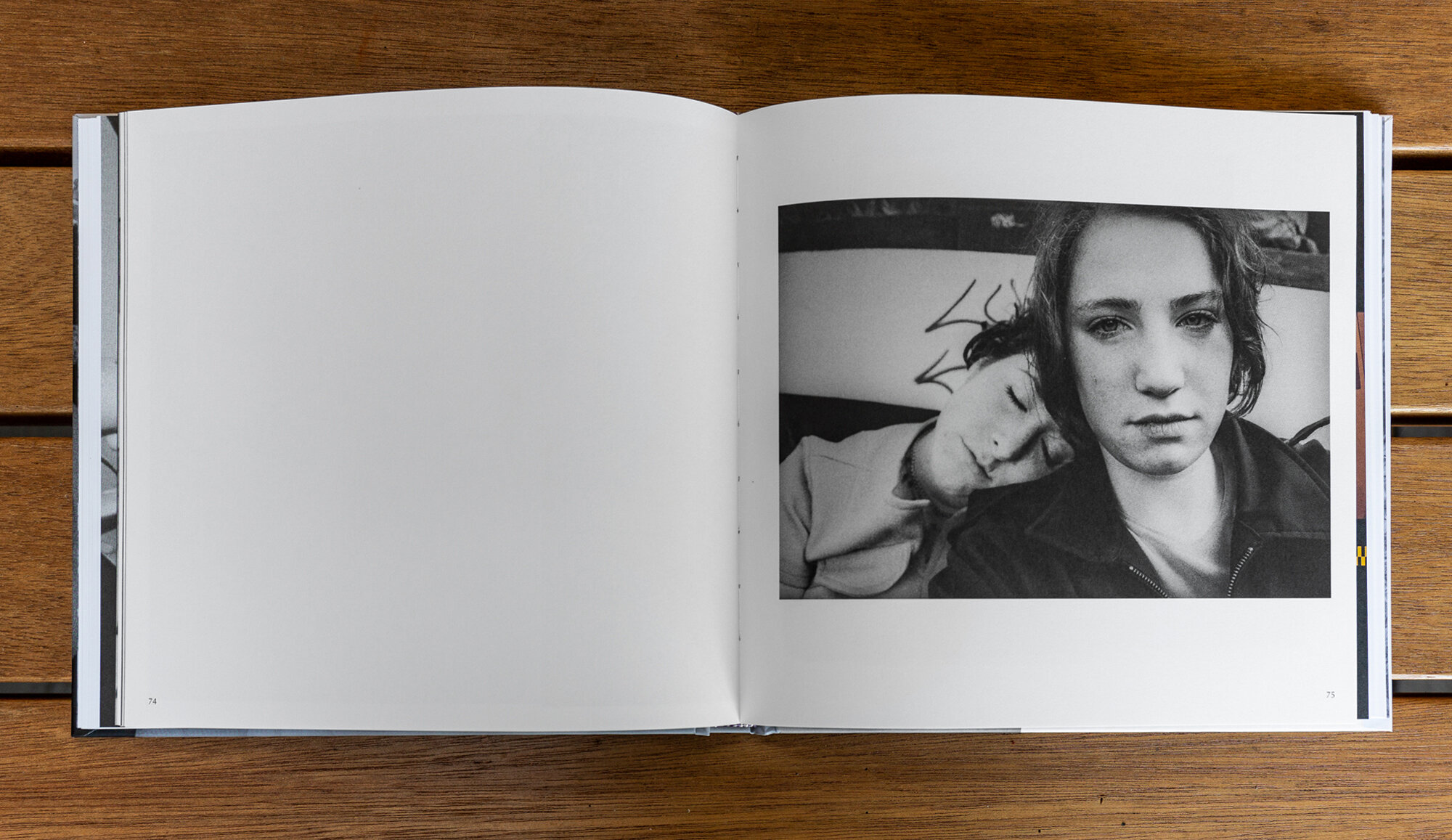

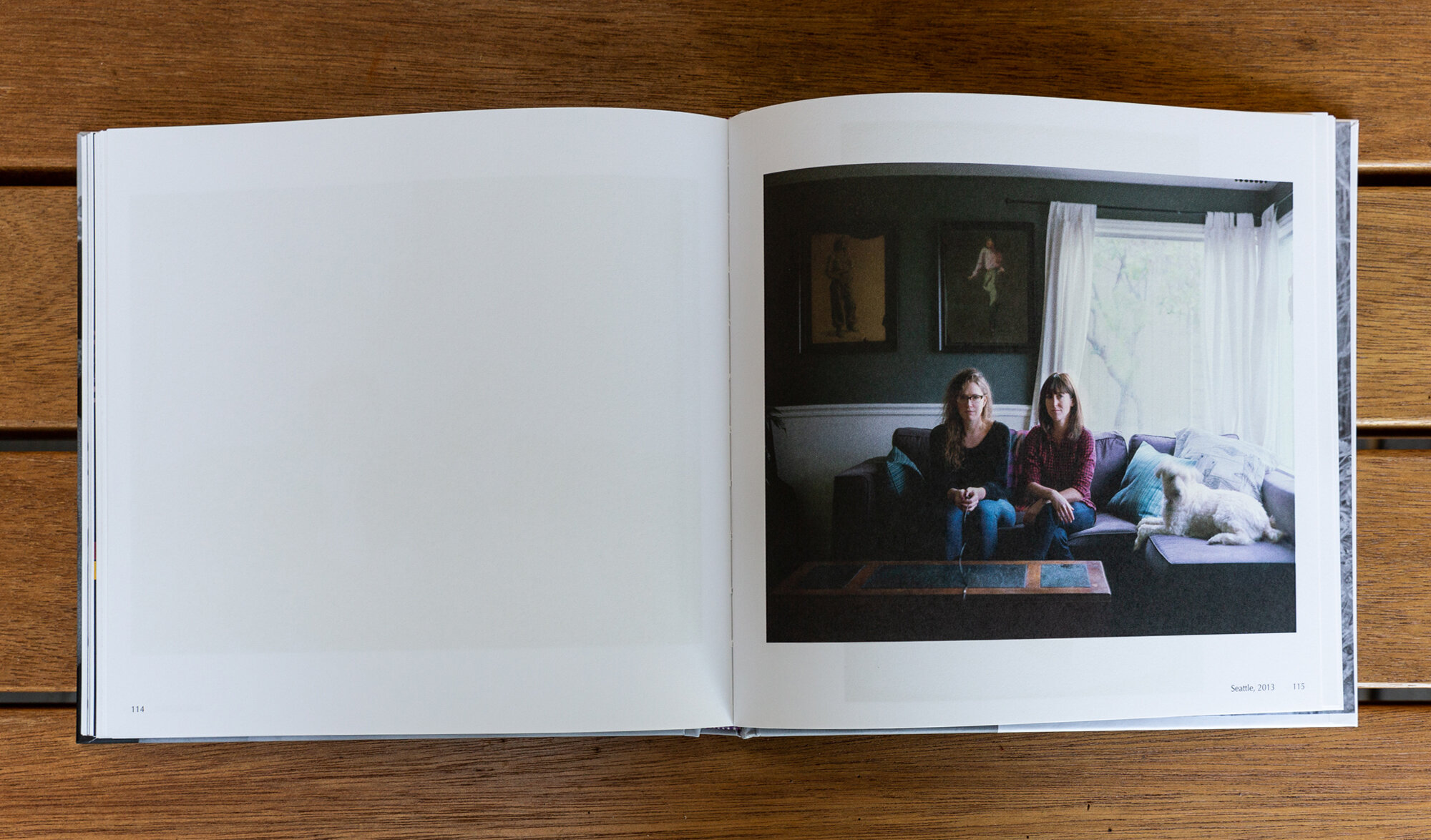

“Molly my dear…” reads the opening page in Riffle’s handwriting, “it just started raining. I love you, Jenny”. In the subsequent pages, Riffle and Landreth picture themselves in moments of intimacy and cheeky displays of affection. As writer Genevieve Hudson notes, they “taught each other what it was like to be friends and lovers and young queer artists at a time when queer representation was hard to find. And since they could not see images of their life reflected in the world, they made images of themselves.”

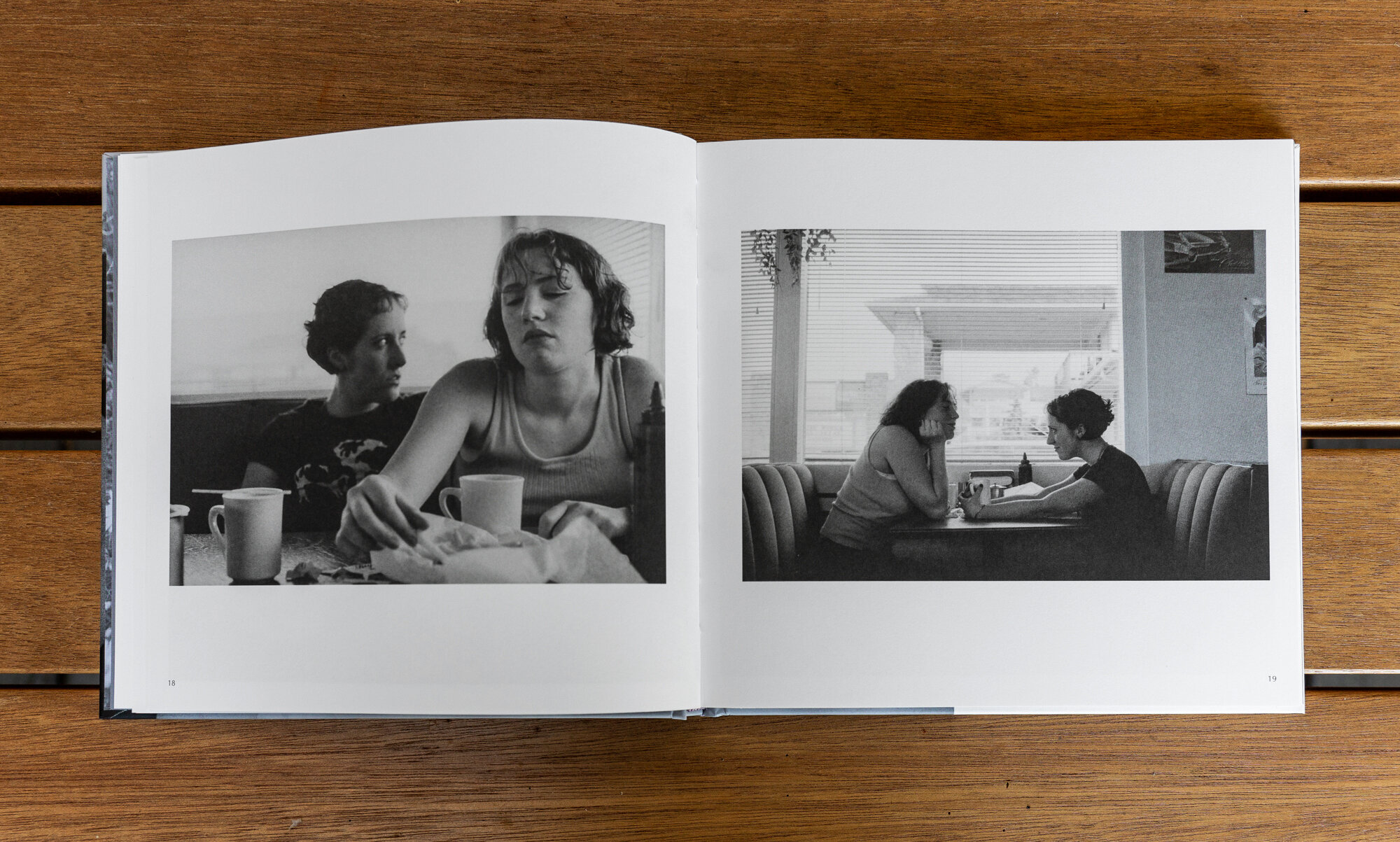

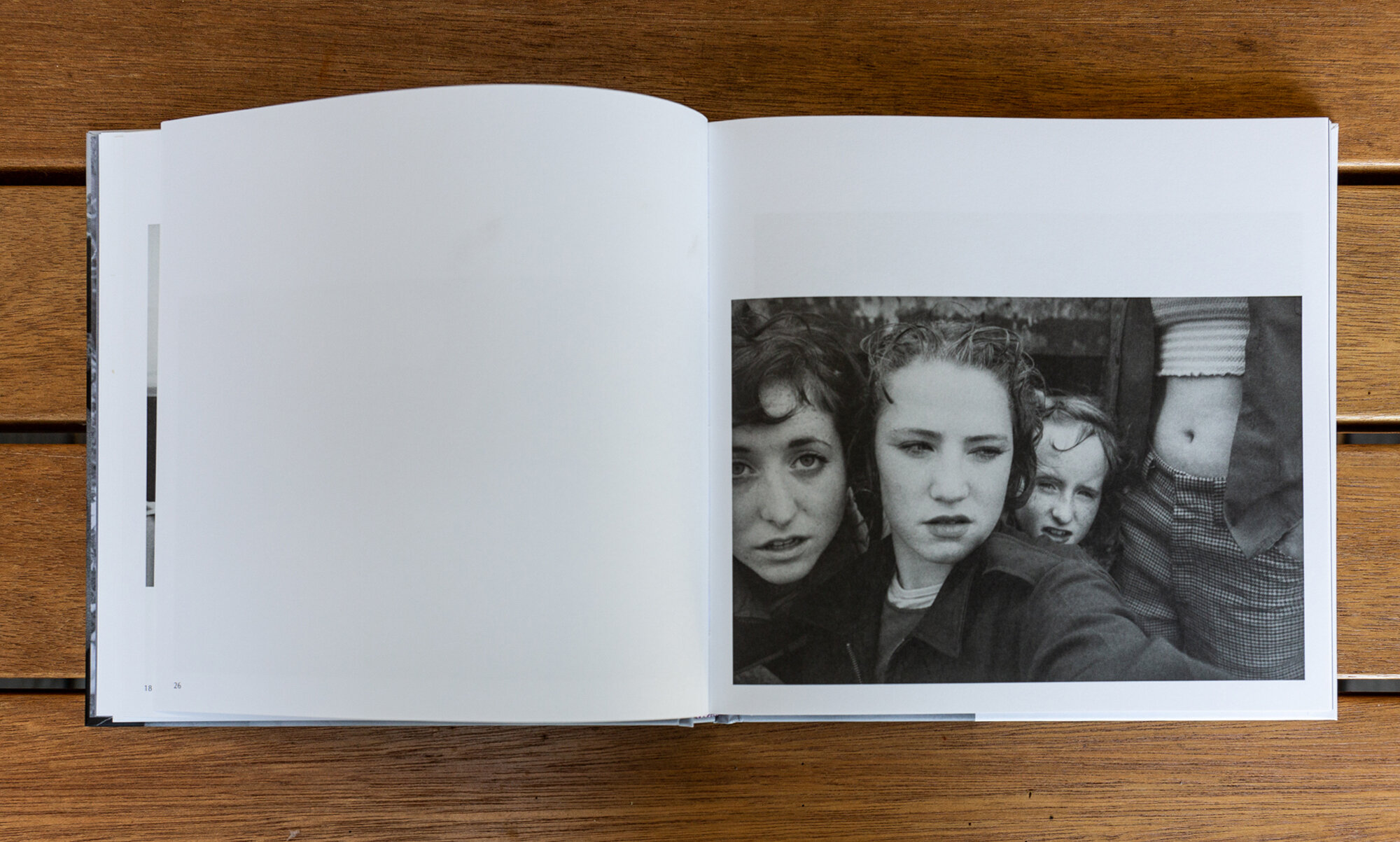

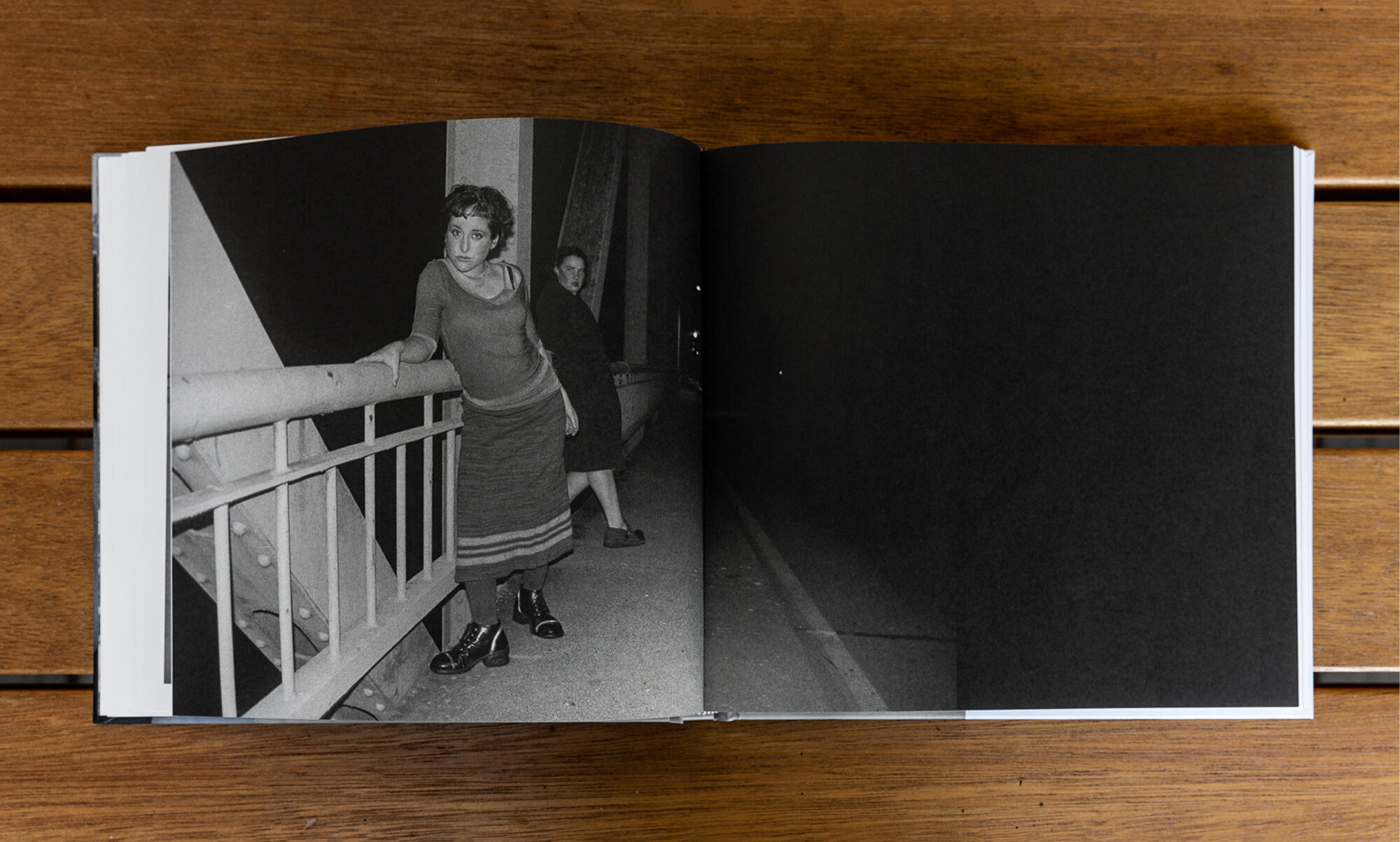

In private spaces we find them lounging together, holding one another tenderly. In public their intimacy carries a performative streak, a daring spirit and often a defiant gaze directly into the lens. As if plucked from a coming-of-age film, Riffle and Landreth’s photographs picture women on the edge of something. Their confidence is youthful and innocent, and yet there is longing—an appetite for answers, a curiosity, a search for love and belonging.

“One day a carnival popped up in the parking lot of our local mall.” Landreth writes, “Immediately Jenny and I put on our best carnival outfits and went to make photographs. There was something deliciously secretive and exciting about our relationship that was amplified when we were in public, in non-queer spaces. I loved that people knew that there was something going on between us, but couldn’t tell what. Sisters? Twins?” A striking image shows a handsome young man, a carnival worker, flanked by Riffle and Landreth, proud with his arms around each of them as he stares into the lens, as if they were his very own carnival prize. Riffle and Landreth’s gaze, however, is locked on each other, cutting directly through him. There’s a smirk, a “deliciously secretive” and magnetic energy between them that makes him nearly disappear—like a queer superpower.

I think often of the great queer thinker José Esteban Muñoz, who wrote that “We may never touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. The future is queerness’ domain. (…) Some will say that all we have are the pleasures of the moment, but we must never settle for that minimal transport; we must dream and enact new and better pleasures, other ways of being in the world, and ultimately new worlds.”

The excitement in these photographs—the tension, the rebelliousness—feels born out of what they’ve yet to know. There’s a clearly buoyant enjoyment of the present, but the essence feels rooted in the future, in the endless possibilities of queer world-building. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the photographs are good. Among the freestyle nature and the playful theatrics one finds in both Landreth and Riffle a curious and sensible eye as well as an obvious technical competence that is critical to the success of this work.

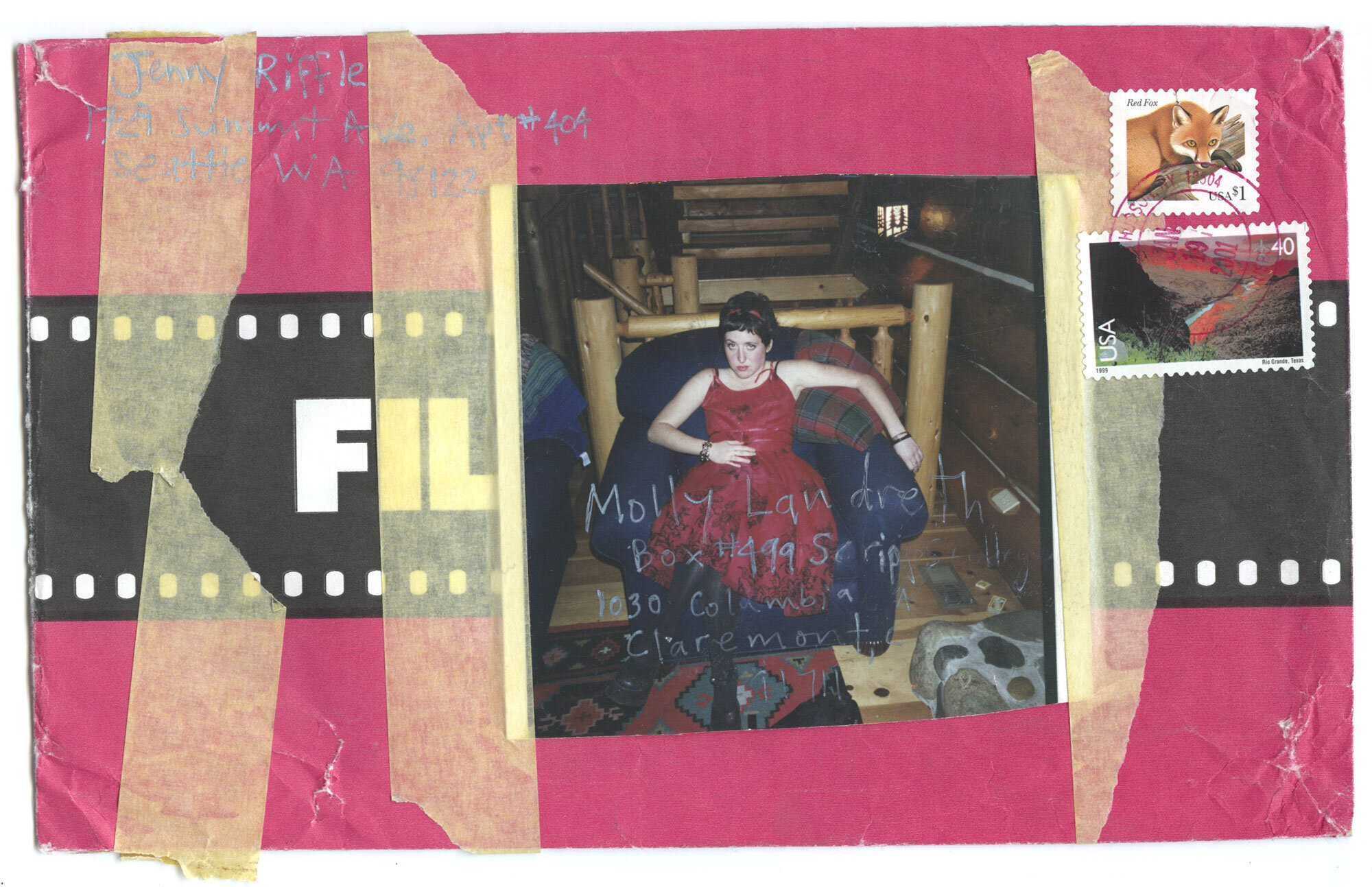

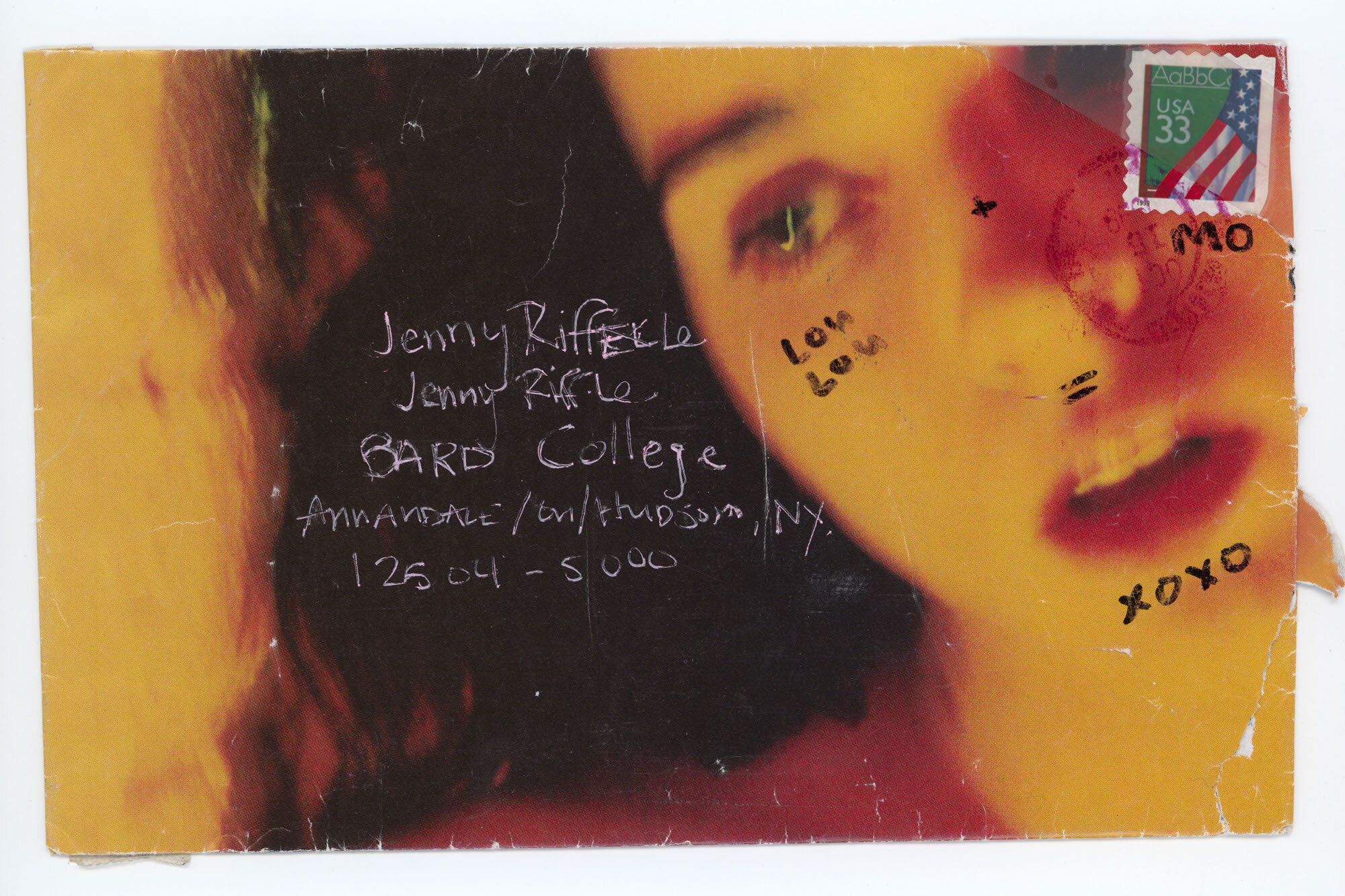

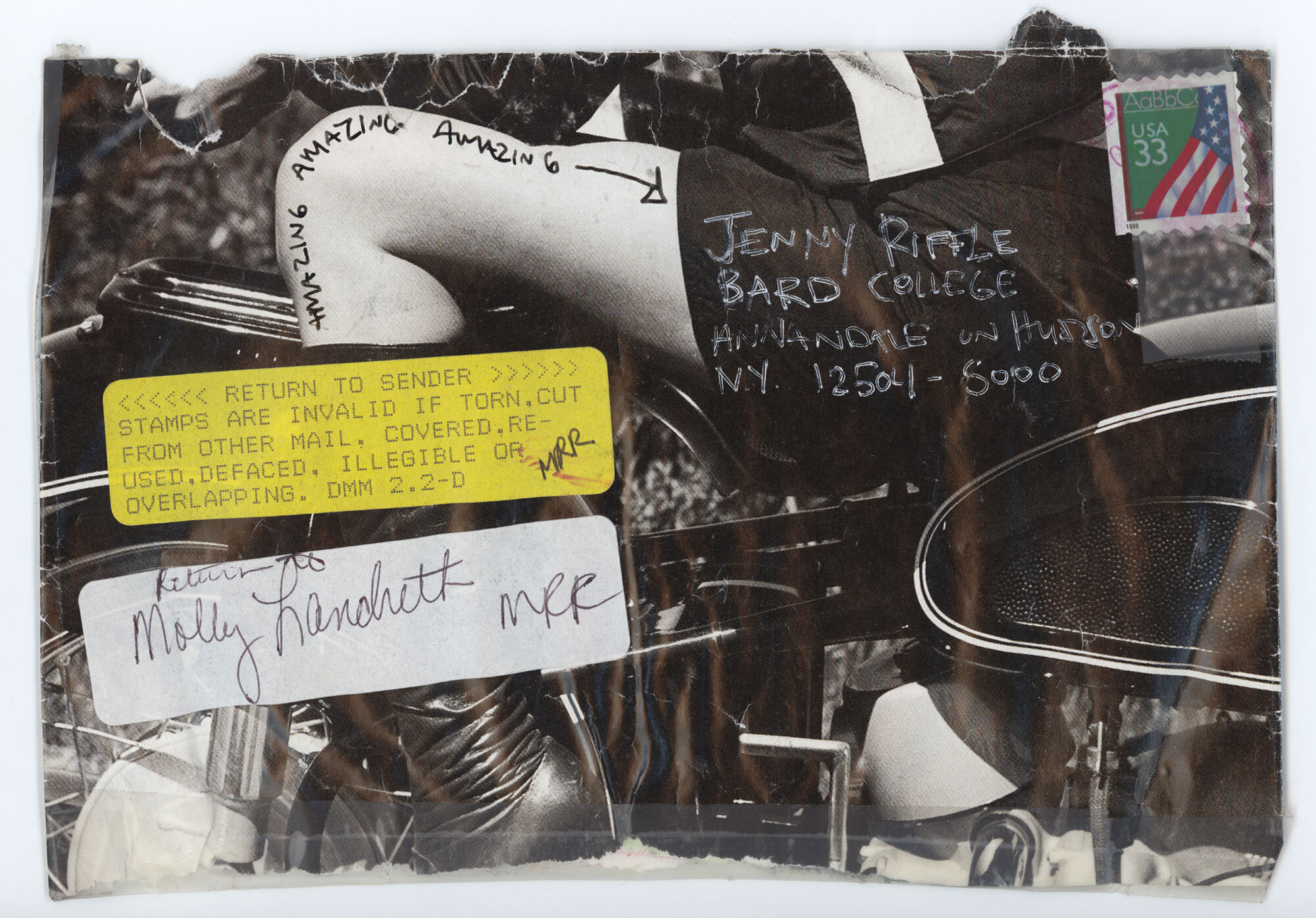

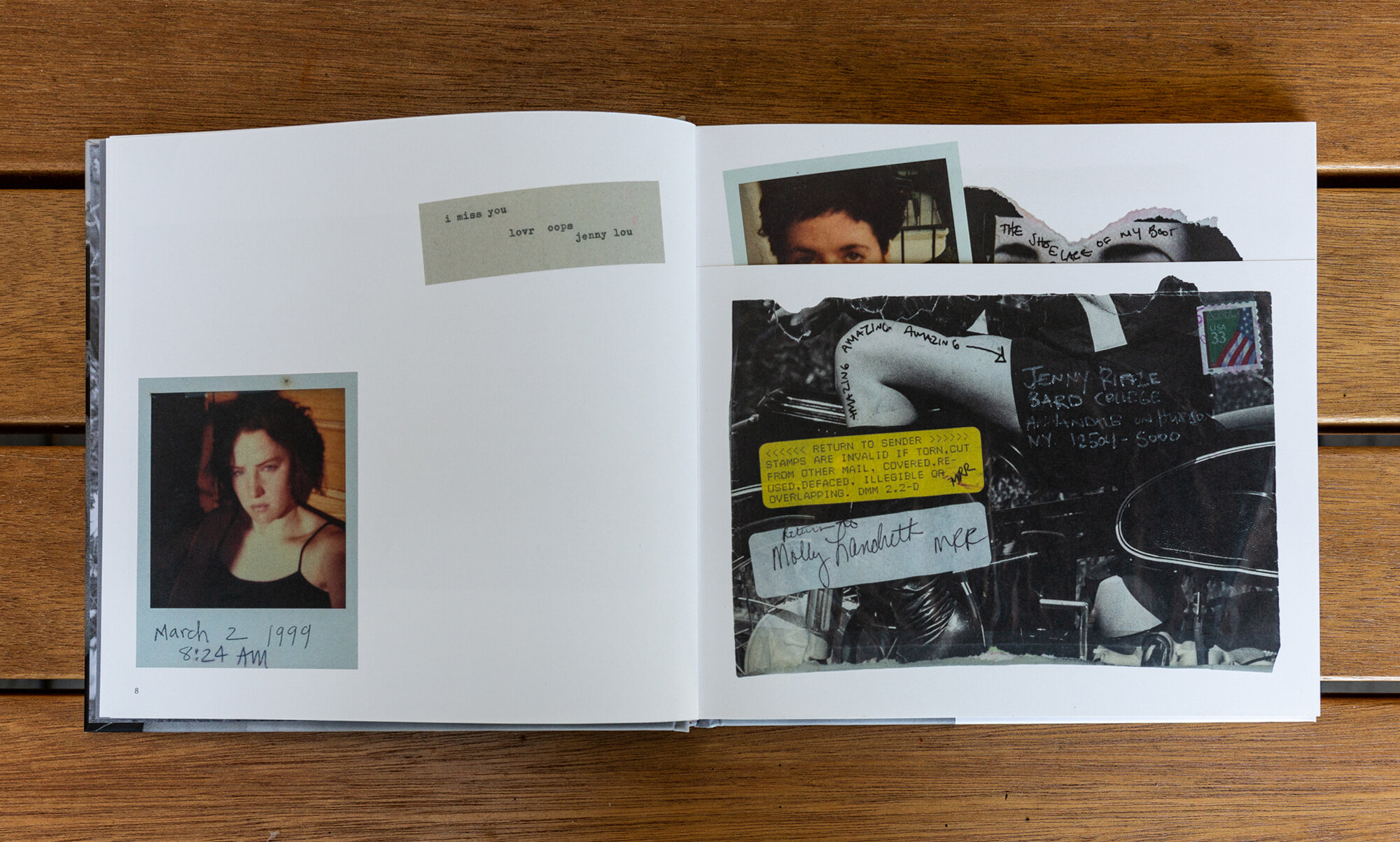

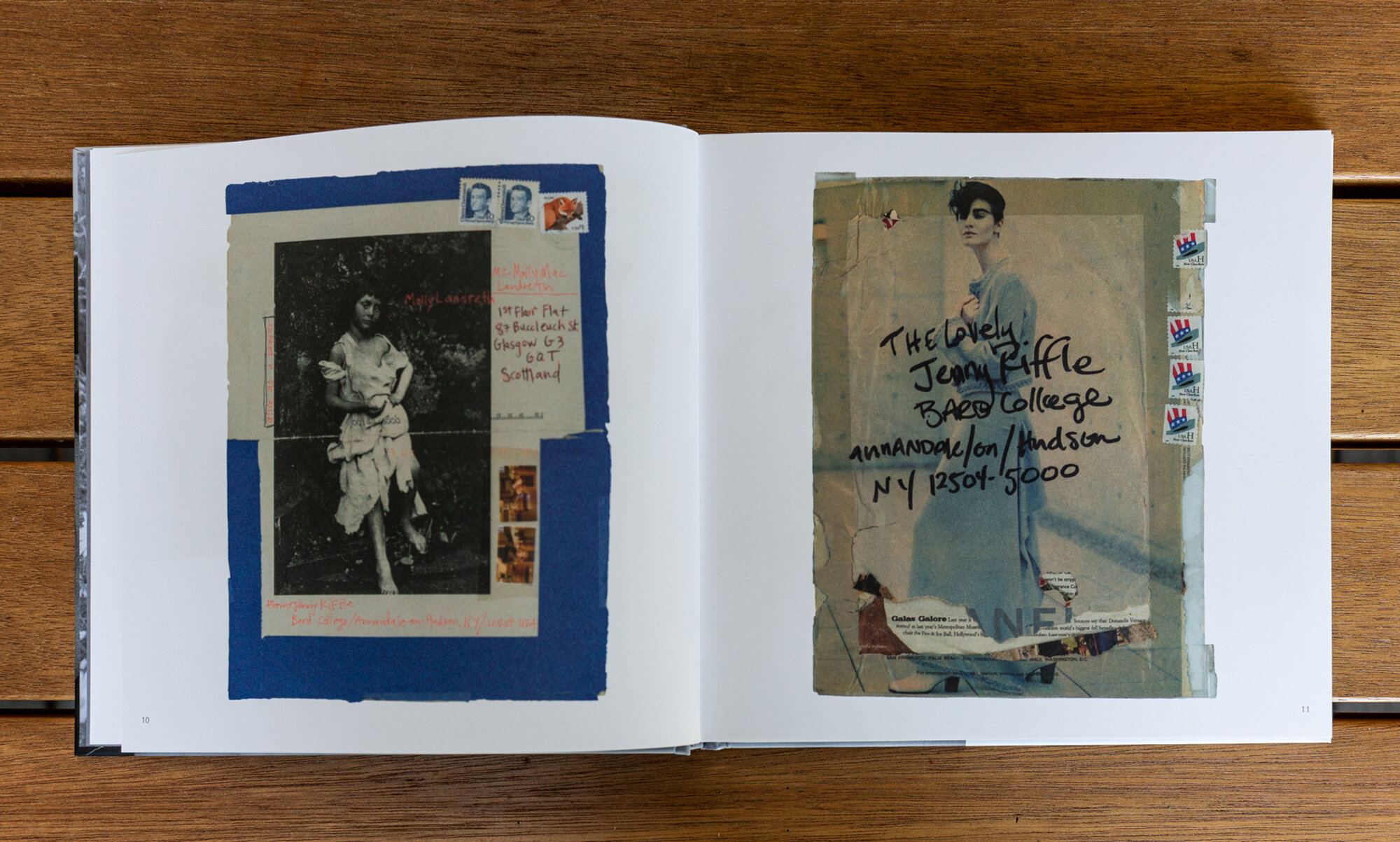

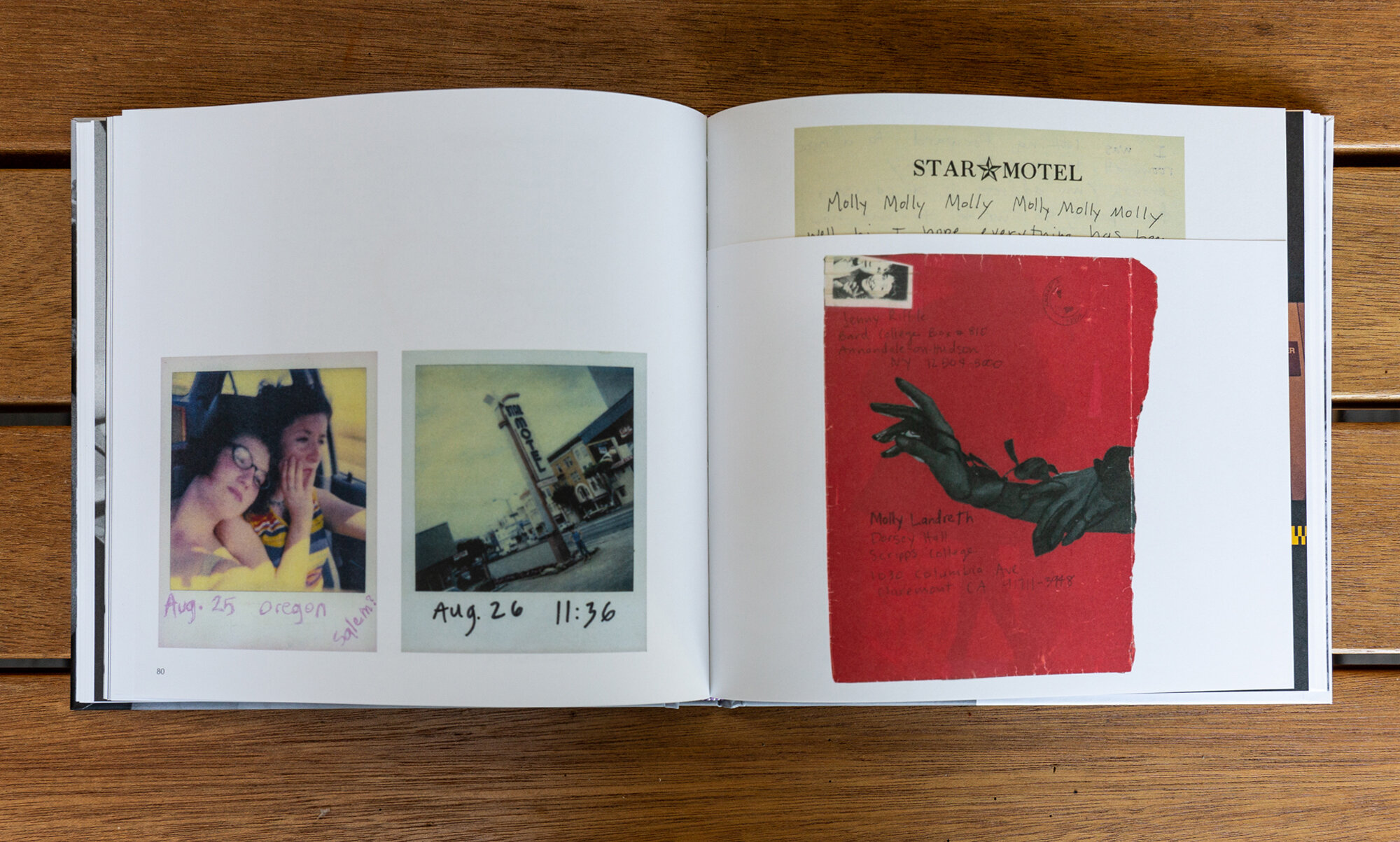

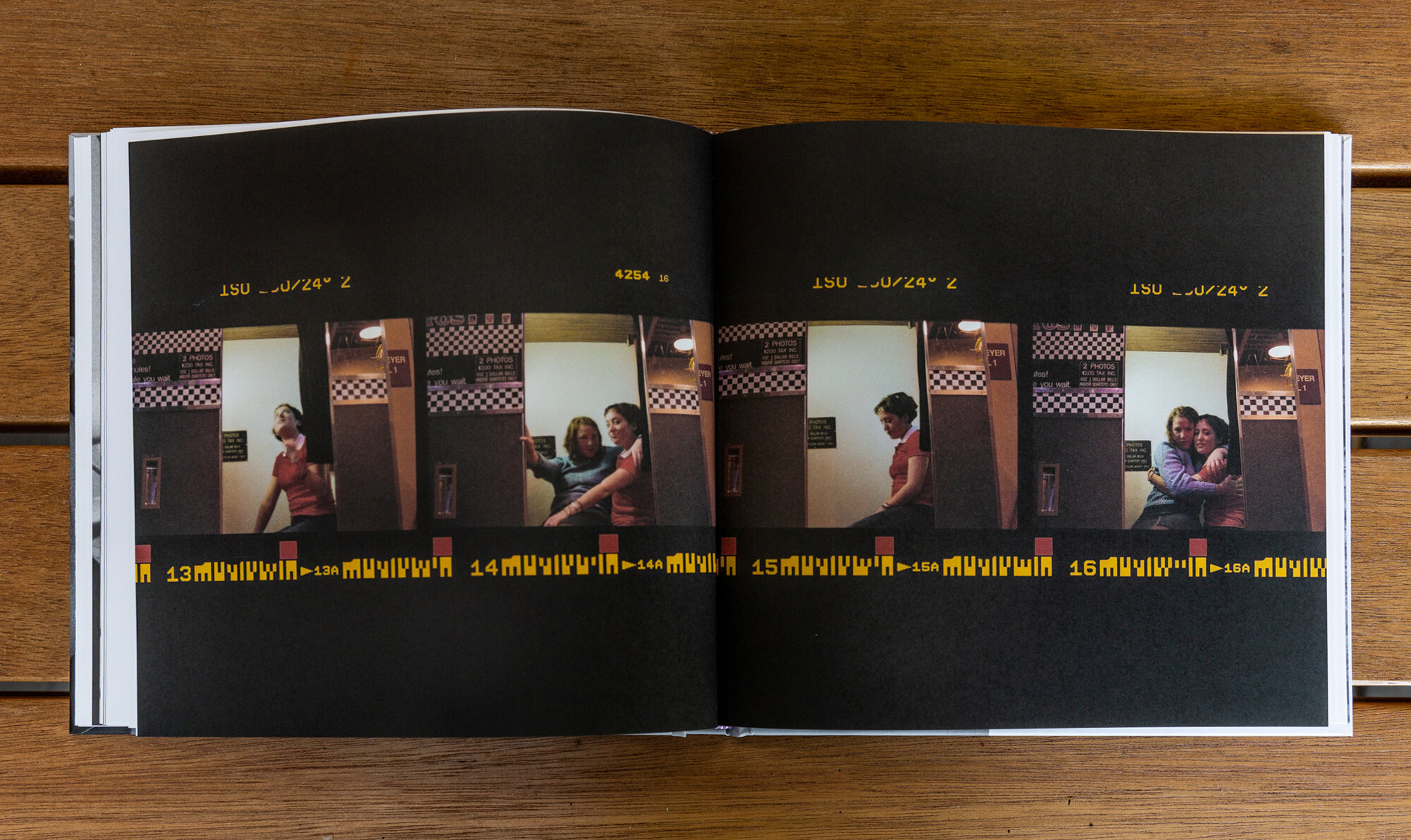

Accompanying the photographs—which take us through daisy fields, bridges at night, abandoned schools, diners, carnivals, and the farmlands of rural Washington—are also snapshots, notes, polaroids, contact sheets, letters, and collaged envelopes. A handwritten note by Landreth reads, “…I took the email as an invitation to come over. I hope that’s okay. So I’m at the Bauhaus [coffee shop] waiting for you. Please join me.” It perfectly encapsulates the urgency of a free, young queer love at the cusp of the aughts and the digital revolution.

“my darling,” begins a typewritten letter by Riffle, “kudos to you for being fucking amazing…” as it continues to negotiate the challenges of their long distance relationship, quickly followed by an impromptu poem, and references to “kissing girls,” Jodie Foster, and her recent dream. In these pages we see two women laying bare their vulnerability and their passion, interlaced with banal observations and struggles of young adulthood. “my windows are stuck open and the ivy is crawling in and the machiene (sic) is roaring outside,” is the last line of another typewritten letter, this time on a torn-off magazine page.

Notably, the envelopes that housed these letters are artworks onto themselves—like a bejeweled pocket holding an intimate secret. These, in contrast to the intimacy of the letters inside, are often outrageous—heavily collaged and adorned with photos of themselves, doodles, quotes, and cuttings from fashion magazines which echo the punk and grunge moment that took hold of Seattle in the 90s.

“The trick is to put enough cream and sugar in it so it doesn’t taste like coffee,” Landreth recalls Riffle saying when she started drinking coffee in New York. “For the rest of that summer I craved the taste of watered-down diner coffee because it tasted just as sweet and rebellious as Jenny’s lips.”

As a queer person I cannot help but think of the ways in which we learn to code-switch at an early age—the cream, the sugar on our deviant identities—and the enduring self-awareness of our public and private selves. In this way, we can consider the envelopes and the letters as the artists’ outward and inner selves. Landreth and Riffle designed these envelopes knowing that they would pass through the hands of many as they traversed the country. Consciously or subconsciously, the envelopes stand out as insubordinate in an apparatus as regulated as the United States Postal Service. Just as the queer dissent in their gaze at the carnival, here they queered the USPS. They too remind me of the flamboyance we queers often use to affirm our identities; the same flamboyance we sometimes use to mask our loneliness, our deepest emotions—to protect our hearts.

With a shimmering silver foil stamp on the cover, and end-papers of daisy fields, this book acts like an archive of a world gleaming with potentiality.