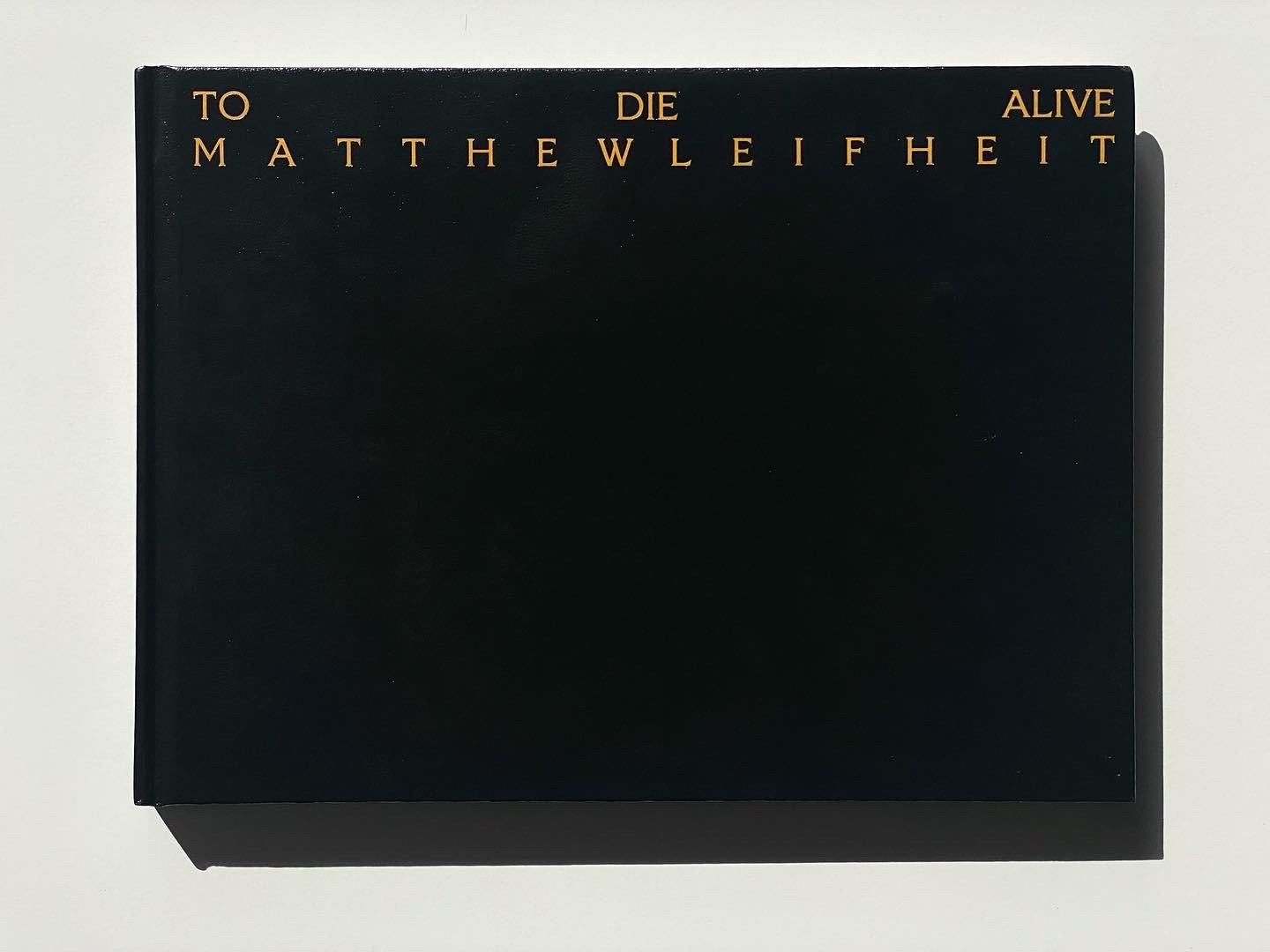

Book Review: “To Die Alive” by Matthew Leifheit

By Kelsey Sucena | April 21, 2022

Published by Damiani Editore in April 2022

Hardcover / 11.5 x 9.5 inches / 144 pages

To Die Alive by Matthew Leifheit, available from Damiani Editore.

I don't know who brings it up first, but we agree that there is some connection between this island and death. Atop a platform, atop a dune overlooking Fire Island, we can spot the site where, in 1850, Margaret Fuller (feminist, literary critic, philosopher, and proto gender-theorist) perished in the island’s surf. If we walked just a few miles east we’d pass the point where Frank O'Hara was struck by a jeep in the dead of night as he lay waiting in the sand. Above us, an Osprey extends her sharp talons into the dying gills of a desperate bluefish. Beneath us, the Sunken Forest drowns, sunken not for its namesake but for the rising seas which daily remind us of the whole island’s vulnerability.

Fire Island is a site of charged cultural consciousness; a ship of Theseus, of sand and stone; A pre-stonewall proving ground for the revolutionary emergence of camp and queer culture; a national park and ecological marvel; An inspiring story of isolation and self-expression, and a victim of its own overwhelming success.

Matthew tells me that he is struggling to carry it all. To tell something of this fluid, this fever, this melancholy, this hyperbole. To encompass the possibility of a sandbar—turned site of sexual revolution—turned real estate capital, to perhaps soon again be turned back into sandbar.

I wish him luck. For myself, I doubt the possibility that something so complex can be grappled with through the limited lens of a camera. As I read To Die Alive I realize that, as I have so often been on this beach, I am once again surprised.

***

To Die Alive (Damiani, 2022) is a hardbound photobook of classical design. Containing 77 photographs by the artist and photographer Matthew Leifheit, as well as essays & poems by Jeremy O. Harris and Jack Parlett, To Die Alive seeks to conjure something of the complex and feverish legacy of Fire Island’s famously queer landscape. In an erotic mess of fire and fluids, To Die Alive paints the picture of a complex community. One tinged with lust, repression, and orgasmic release.

From the flamboyant halls of the Belvedere Guest House for Men, to the secluded and seedy sands of the Meat Rack, Fire Island has long been a space of gay male fantasy. Owing to its relative isolation and the historically uneven class dynamics of Long Island’s south shore, the island is among the earliest sites in the United States to be openly associated with queer life and culture. In this way, it has cemented itself within the imagination of generations of queer people, especially within the consciousness of gay men, who, like pilgrims to the holy land, embark for its quartz/garnet beaches every summer.

Captured here by Leifheit as a series of performative vignettes, the erotic queerness of Fire Island is set against the imposing veil of night. Like the island itself, the night is a subject made physical as it envelops the bodies of its voyagers. Through the darkly lit and tacky halls of the Belevedere, to the ecstatic and chaotic dancefloor of the Ice Palace, the nude (or barely clothed) bodies of gay men become entangled, fronting their youth and experience, their beauty and anxiety.

What To Die Alive gives us is a rare but sincere alternative to the rainbow-clad floats of a New York City Pride. Here we can begin to imagine a reciprocity of sorts; that of visibility and shadow, of birth and of death. Indeed, the historic landscape of Fire Island’s queer reputation is more a product of shadows than of light. Of invisibility, shrouded as the island is by the expansive wall of the Great South Bay.

In considering Fire Island’s fame it is useful to also consider its trauma. The challenges of homophobic retaliation. The long and painful legacy of the AIDs epidemic. The exclusionary nature of a queer economy produced by and for a privileged and wealthy few. The ever-present danger of climate change which threatens to erase it all.

In this way, Fire Island is a hauntological landscape, marked by the promise of a queer utopia but set against the erosion of both history and hurricanes. In rejecting the plain assessment of a place so fetishized, Leifheit emerges with something more. Something both seductive and terrifying. The hungry ghost of a queerness yet to come.

***

We’re done chatting now and I tell Matte that I’ve gotta go back to work. As he leaves for the forest I glance back toward Point-O-Woods, the spot where Margaret Fuller lost her final manuscript, her family, and her life. I have been bitter about that shipwreck since the day I learned of it, knowing that what Fuller had to offer the world was itself a revolution. In her seminal book Women in the 19th Century Fuller writes: “Male and female represent the two sides of the great radical dualism. But, in fact, they are perpetually passing into one another. Fluid hardens to solid, solid rushes to fluid. There is no wholly masculine man, no purely feminine woman.” Here, my transexual/nonbinary heart skips a beat.

Those words echo out from 1845 like a spirit hollering through the phrag at dusk. Imagine its possibility. Its promise. What might have happened had she lived to keep writing? What might have happened had not so many perished due to AIDS? What would the world have looked like had Fire Island not been here to wreck that ship? Had it not also been here to provide shelter and sun to O’Hara and so many others? Like the tides which daily reshape the island, so too does its history give and take.

This, I think, is what we mean when we say that there is something between this island and death. So much triumph, so much tragedy.

If we are to die, I think to myself, then let it be here.

Where, at least, we are alive.

To Die Alive is available from Damiani Editore. Images courtesy of the artist.