Book Review: “red summer” by casey ruble

By Jess T. Dugan | March 4, 2020

Published by Conveyor Studio, 2019

Softcover / 126 pages / Limited edition of 100 copies, signed and numbered by the artist

Both within and outside of the art world, many conversations are taking place about representation, equity, and inclusion. Whose stories are, and have historically been, told? How do these stories create a partial, and often revisionist, history? Whose perspectives are favored, and at what cost? We live in an America that routinely denies the violence of its past, often holding on so tightly to a romanticized version of our country that we are unable to reconcile the darkness of its reality. And, without this necessary reconciliation, we are unable to move forward towards a more just and equitable society.

Casey Ruble’s research project and subsequent publication, “Red Summer,” examines these questions, taking as its subject matter the omission of people of color from a series of artworks at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. The title of the book refers to the year 1919, of which Ruble writes:

1919 marked the deadliest period of interracial violence in U.S. history. D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film “The Birth of a Nation” had inspired the revival of the Ku Klux Klan, the white media spewed anti-black propaganda, and thousands of African Americans were moving north to escape the terrorism of lynching and Jim Crow. Above the Mason Dixon line, towns were passing – and unequally enforcing – “quality of life” laws as a means of preserving segregation in the North. Across the country, postwar competition for jobs and housing was fierce, and wealthy industrialists pitted white union members against black workers by using the latter as strikebreakers. African American World War I veterans, many of whom served in the hope that their efforts would advance civil rights by exposing the hypocrisy of a country that fought for democracy abroad but denied it at home, had experienced rampant racism in the military and returned not to a hero’s welcome but to a nation just as discriminatory as it was when they left… This volatile social climate culminated in race riots in over thirty cities, nearly all started by white mobs that brutally attacked black communities.

1919 was also the year that the Smithsonian Institution began planning the National Portrait Gallery (it opened in 1968), whose mission has been “to acquire and display portraits of men and women who have made significant contributions to the history, development, and culture of the people of the United States.” In 2016, funded by a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, Ruble set about systematically recreating every portrait from 1919 in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection. Notably, and problematically, all of the subjects in the museum’s 47 paintings, drawings, prints, and photographs from 1919 are white. As Ruble writes,

They include presidential advisor Edward Mandell House but not presidential advisor Booker T. Washington; author Thornton Niven Wilder but not author W. E. B. Du Bois; community organizer Mary Harris Jones but not community organizer Ida B. Wells; environmentalist John Muir but not environmentalist George Washington Carver; composer Charles Martin Loeffler but not composers Eubie Blake or Jelly Roll Morton. These exclusions not only evidence the racial bias of the time but, as a historical record, also continue to perpetuate it.

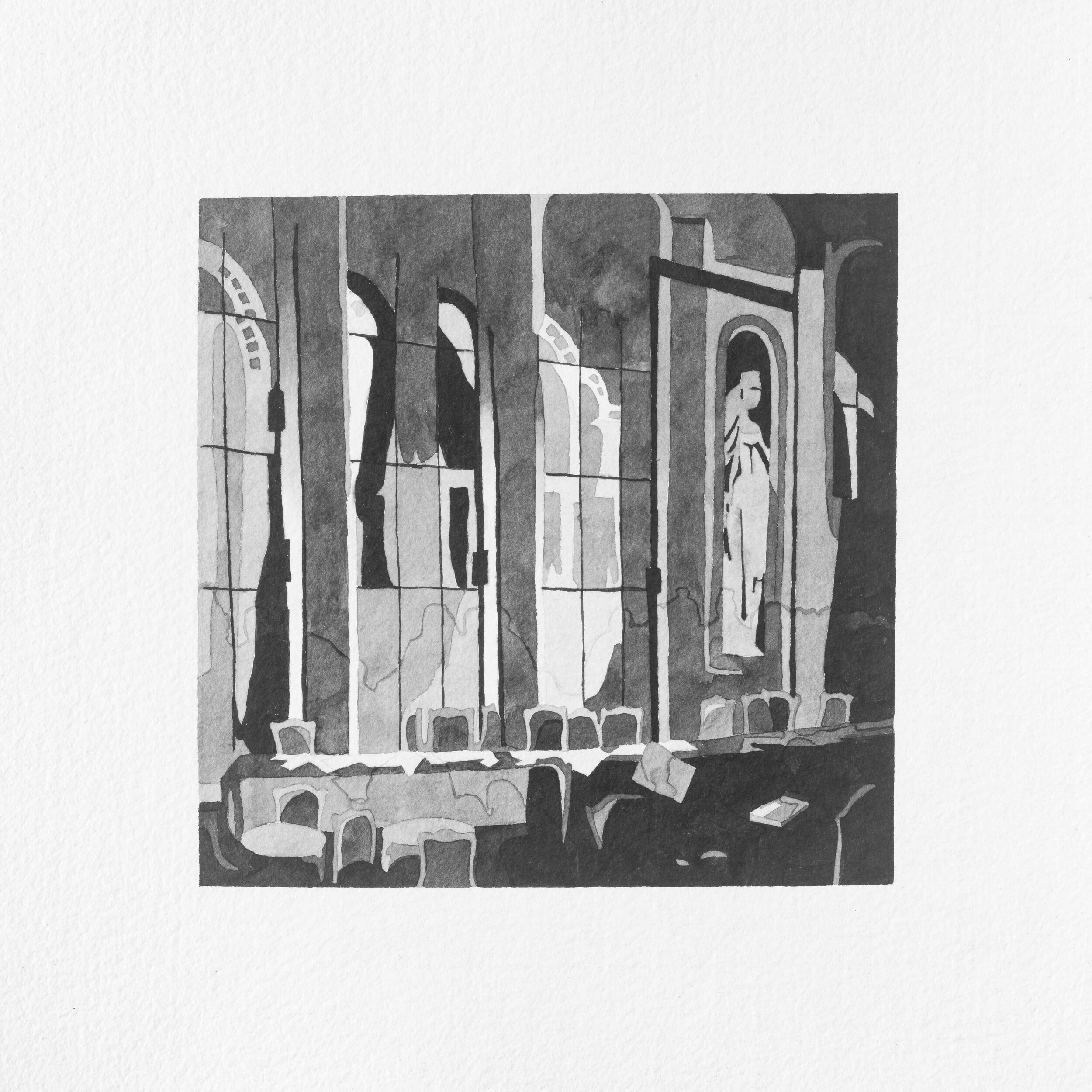

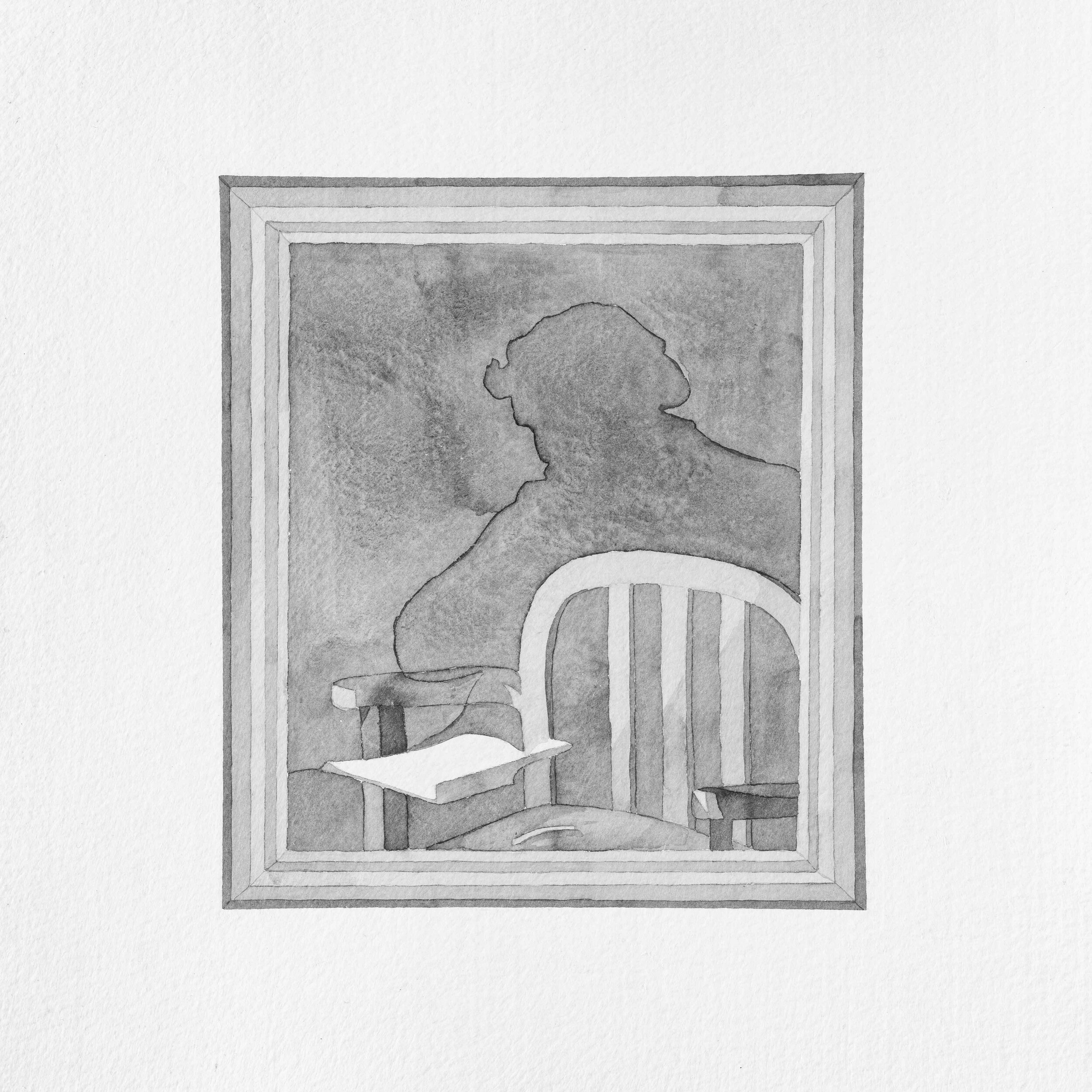

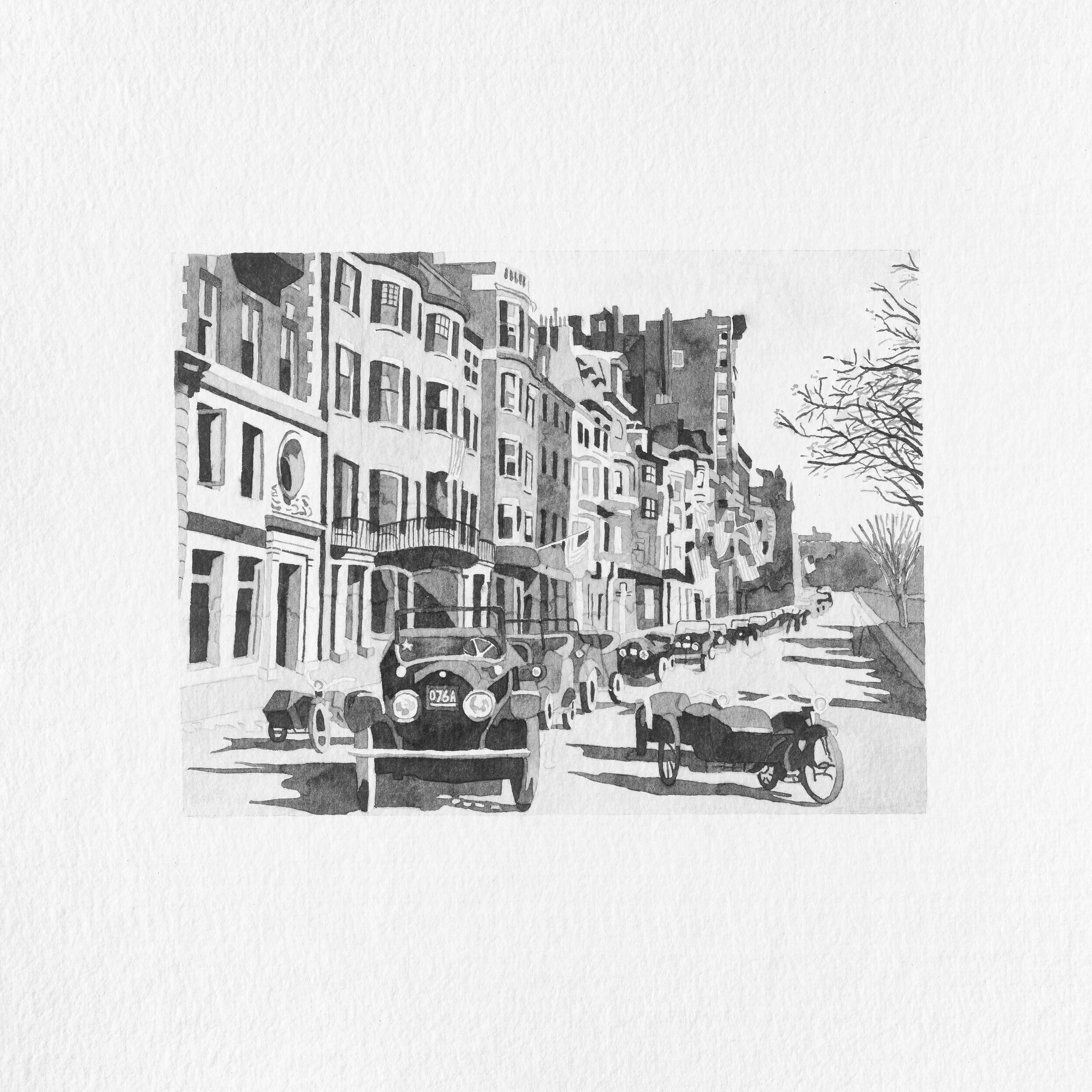

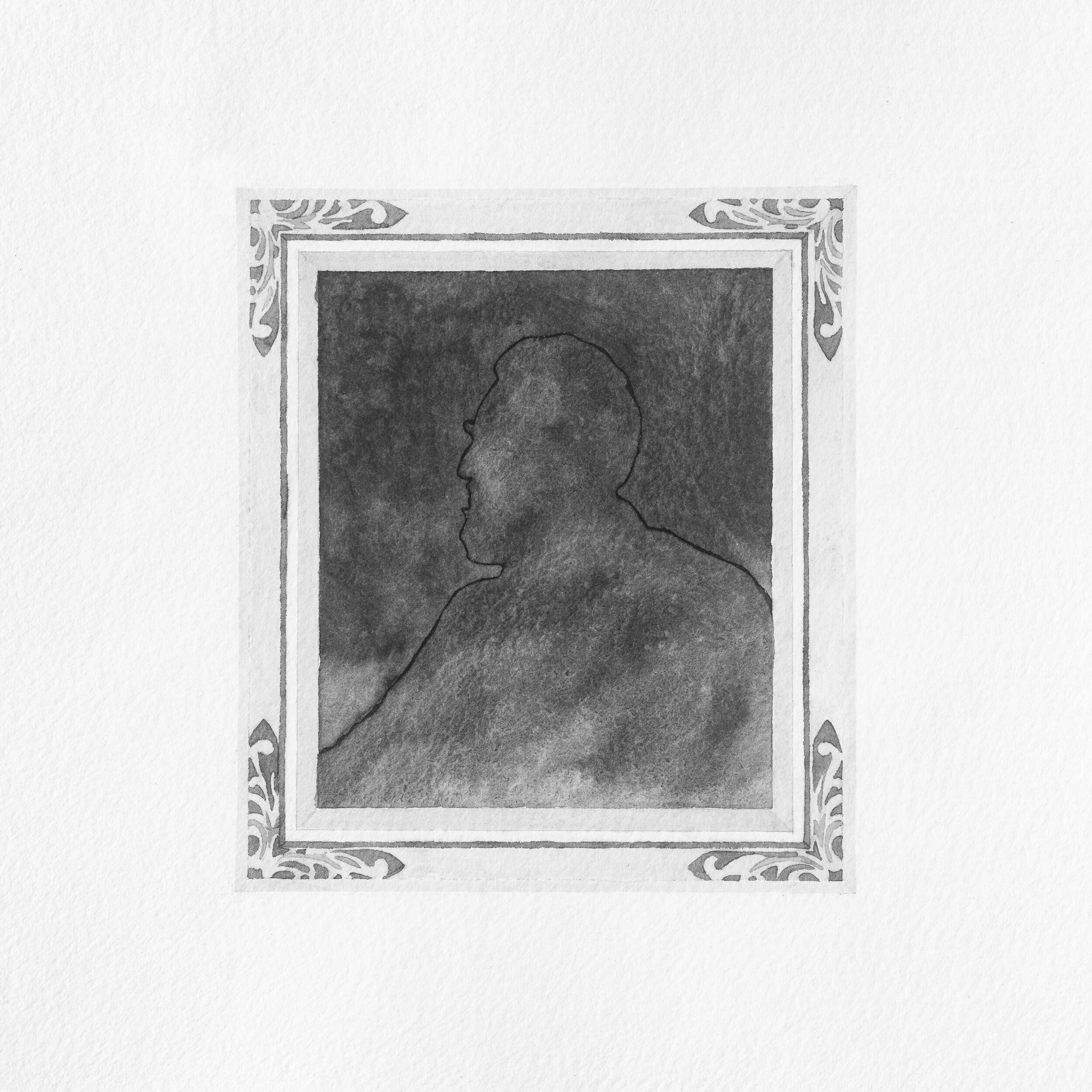

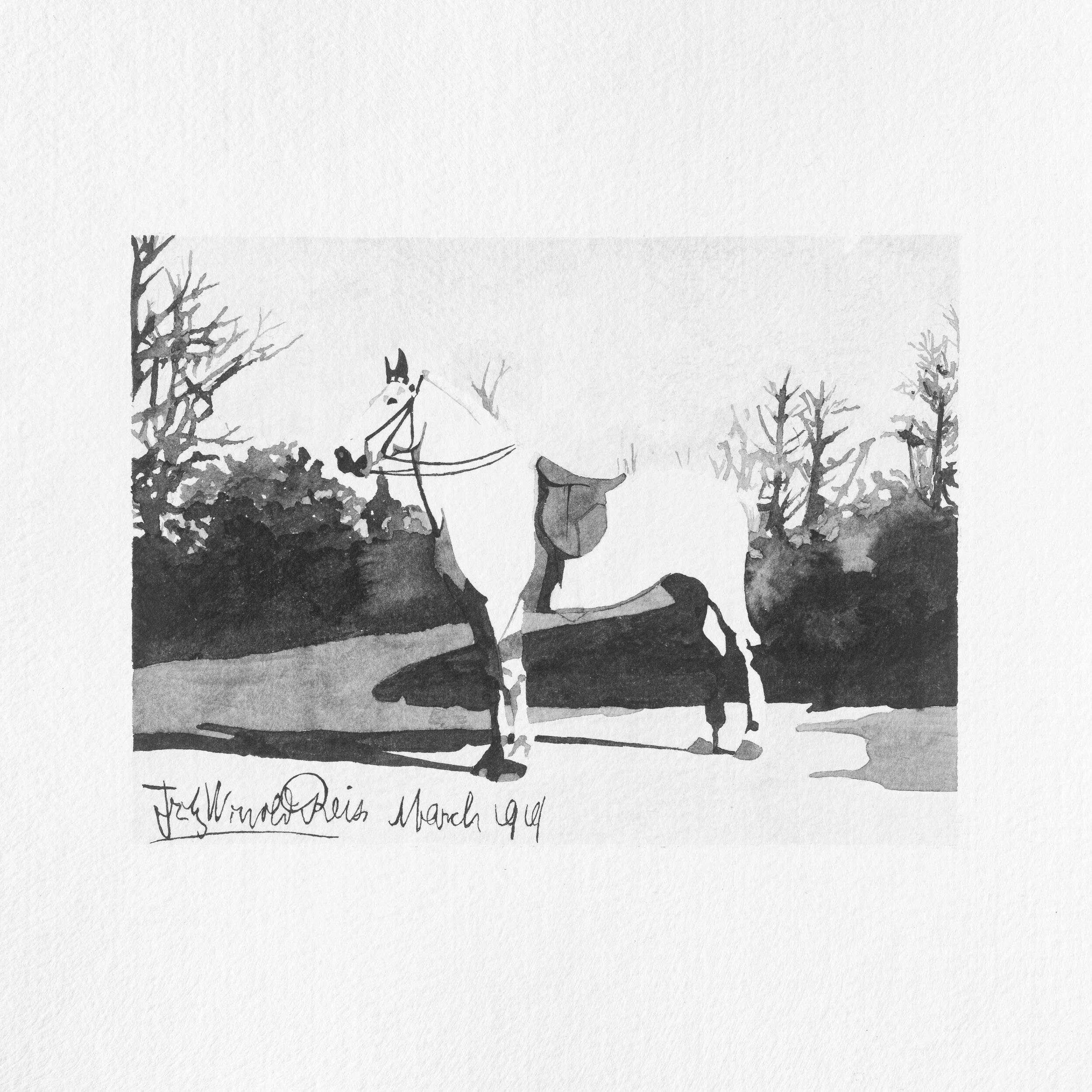

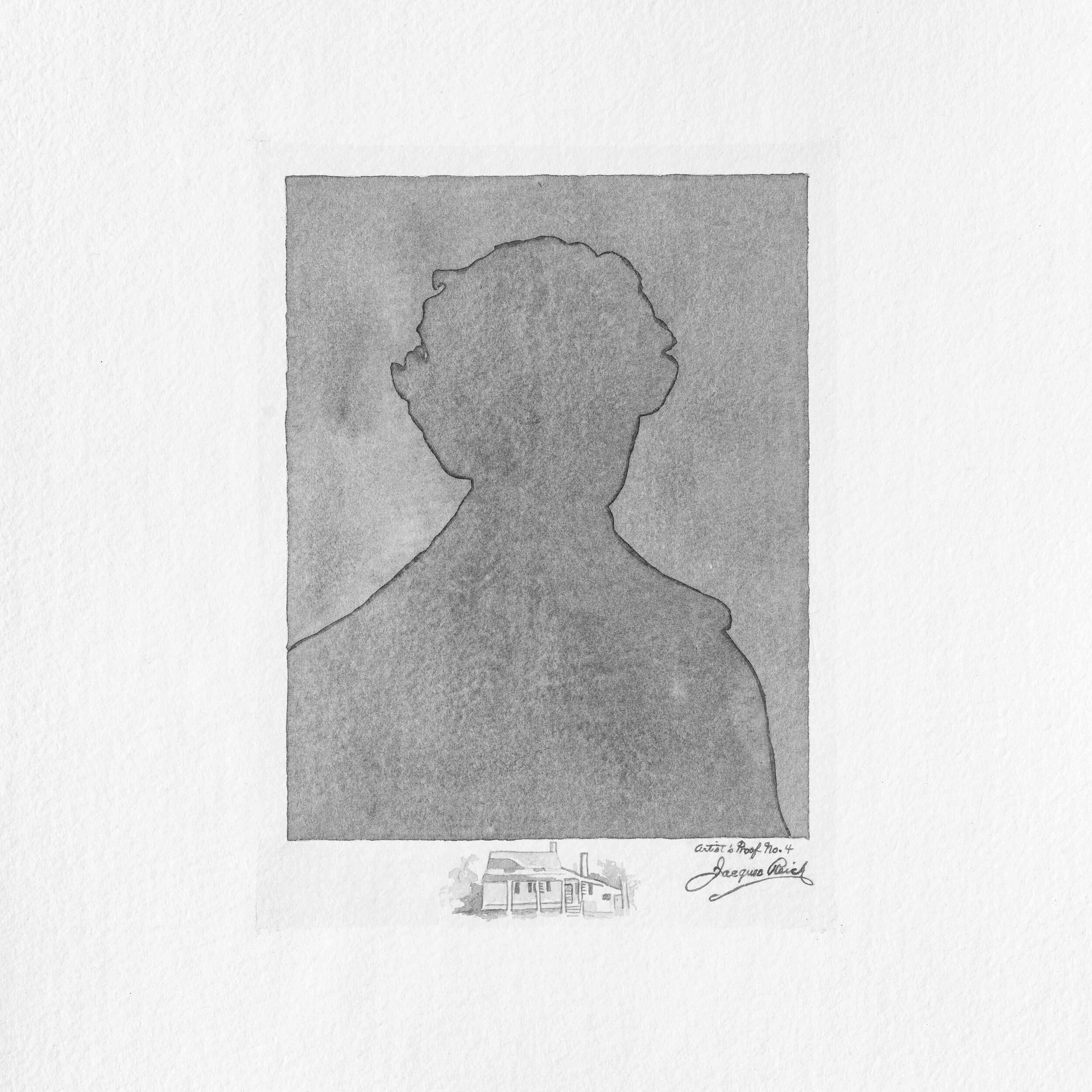

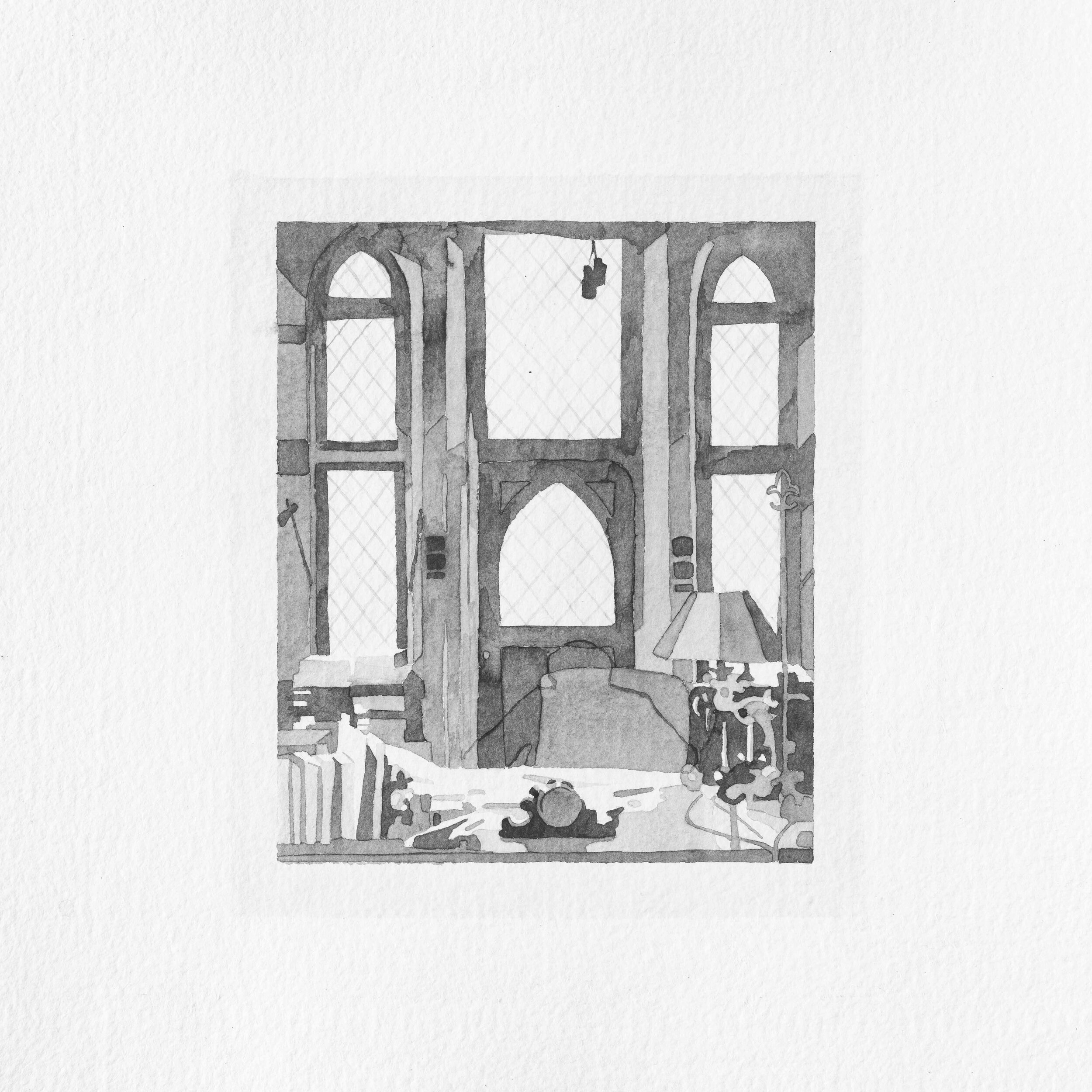

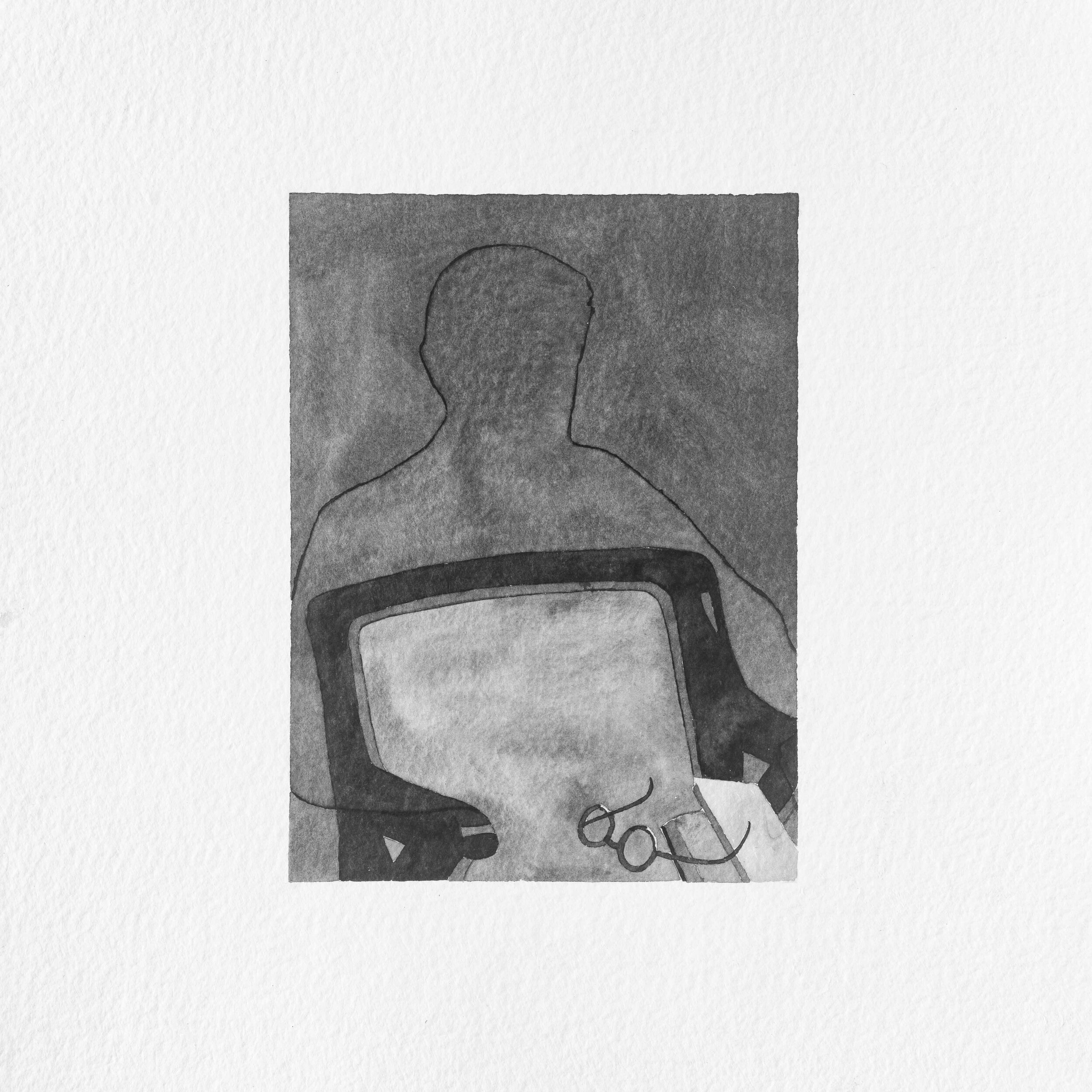

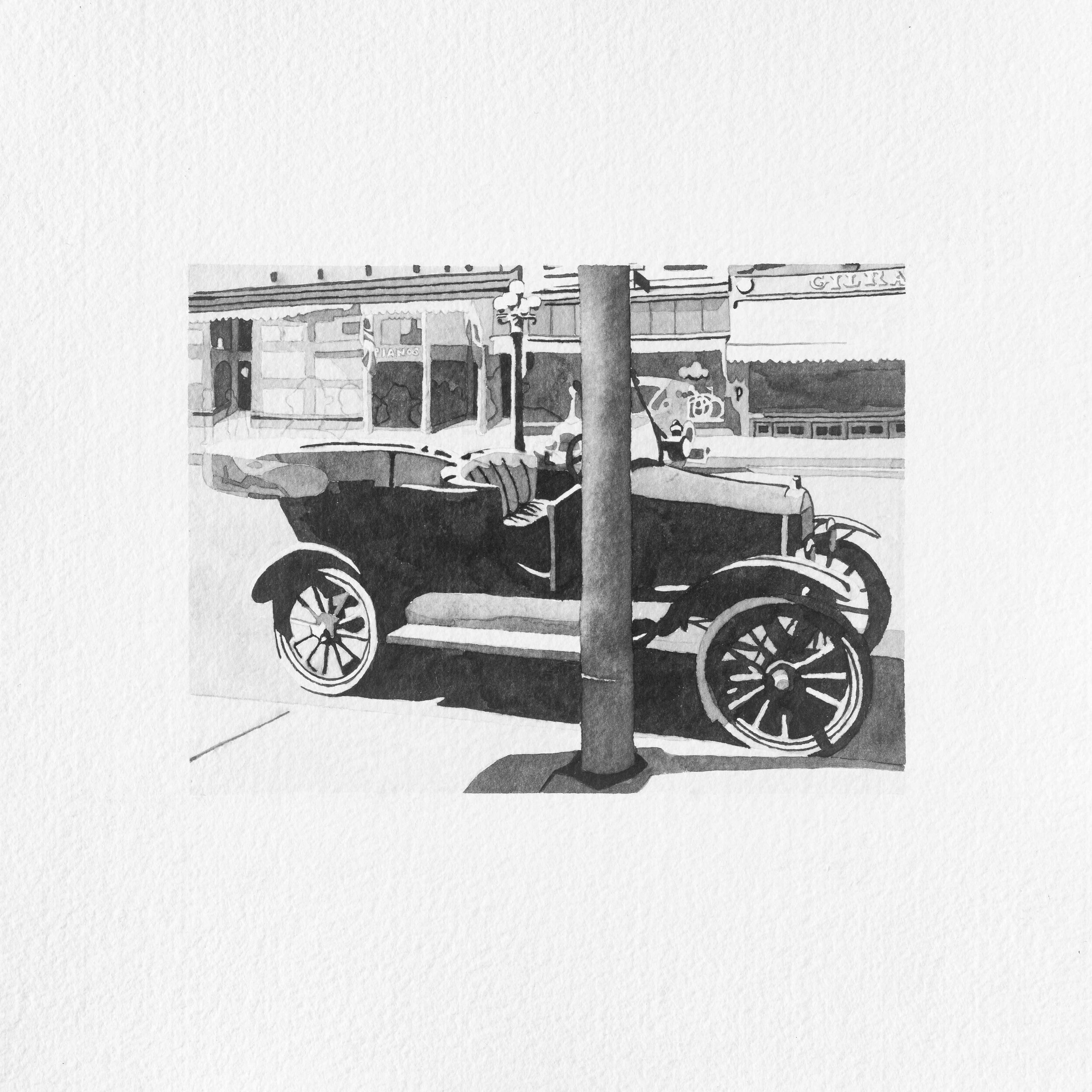

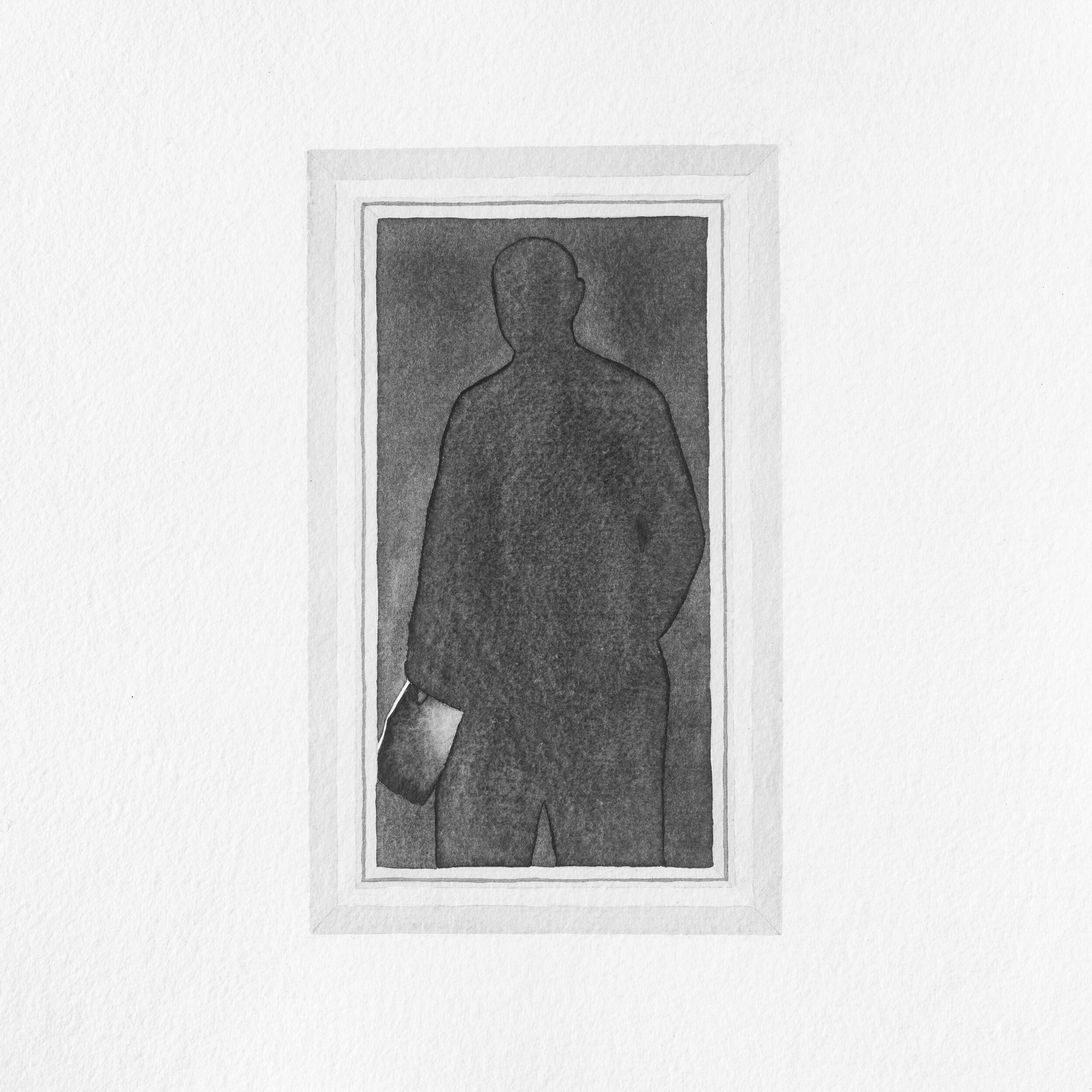

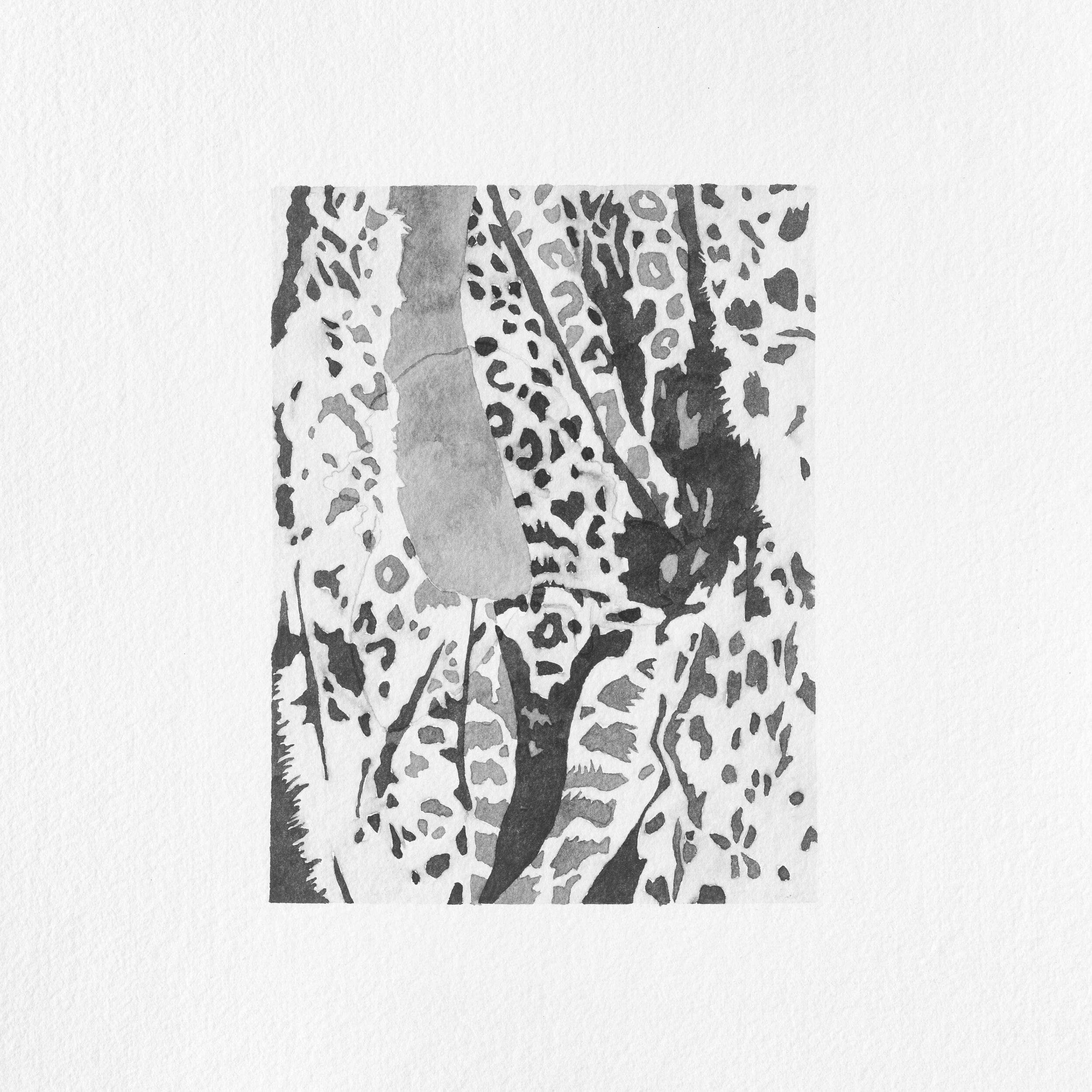

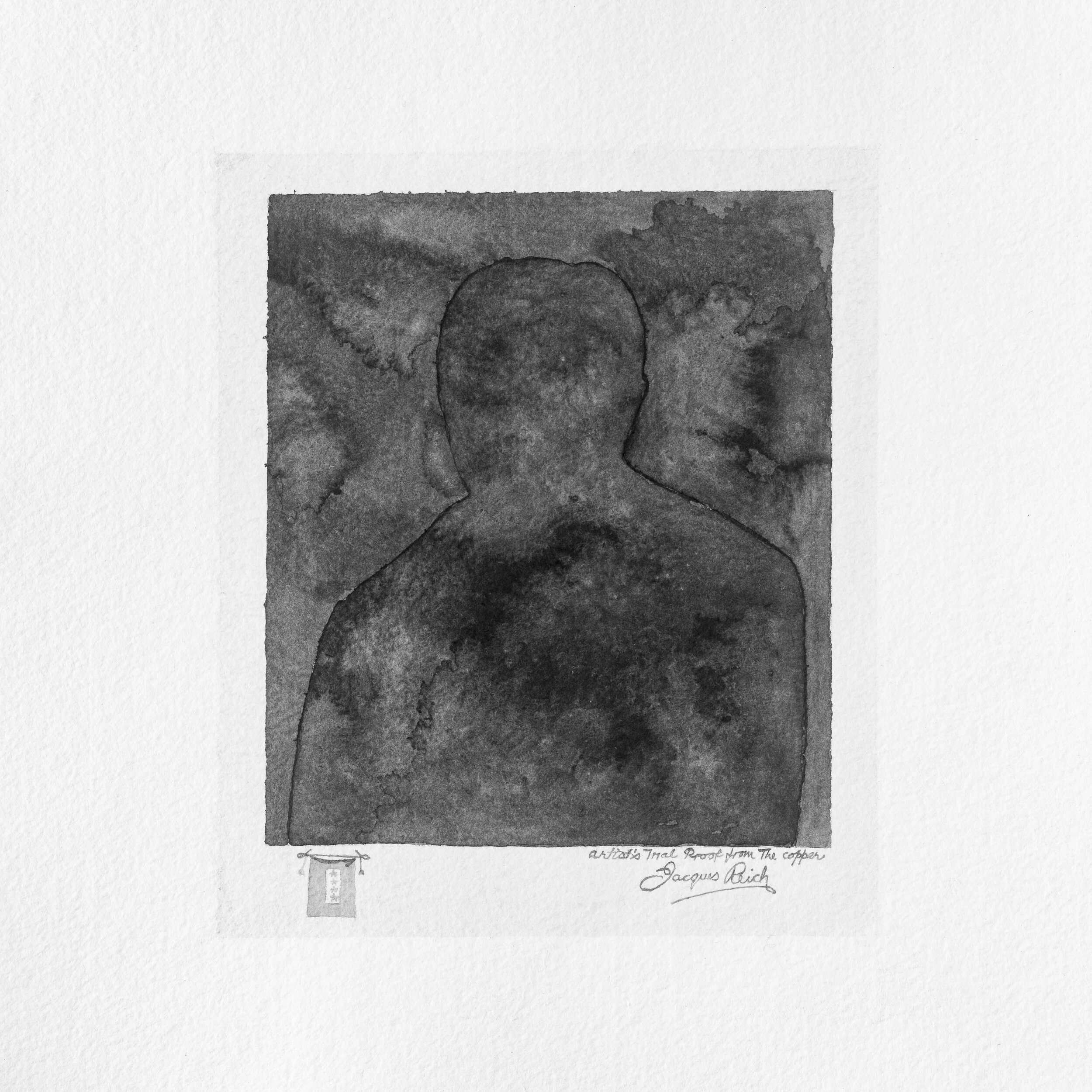

Ruble carefully re-rendered all 47 of these works in ink on paper, but with the subject redacted. She leaves a trace of the figure, and, importantly, her works are titled with the names of the removed subjects, linking her new paintings to the original works in the museum’s collection. Each work is rendered in grey ink, which unifies diverse works made in a variety of media and color palettes. Because of the lack of the subjects, Ruble draws a heightened awareness to the environments, calling attention to how place implies class and power. With the specifics removed, the viewer is also left to consider pose and gesture and the ways in which these elements have historically been used to craft propagandistic narratives that promote some people and groups through the oppression of others.

The book includes an introduction and afterword by Ruble and an essay by Arlene Keizer, Chair and Professor of Humanities and Media Studies at Pratt Institute, as well as a scholar in the fields of African Diaspora literary and cultural studies, critical theory, feminist theory – especially black feminist theory – and psychoanalysis. These writings are significant, addressing both the historical content of the work as well as Ruble’s personal interest in, and process of making, the work.

In her introduction, Ruble compares 1919 to the present moment, asking us to consider how far removed we really are from those events of institutionally sanctioned violence and oppression.

Parallels can be drawn to our more recent rethinking of the story of our nation’s history; What gets rewritten, and how, and by whom? It perhaps is no coincidence that I began this series around the same time that Confederate flags on state buildings were removed; that monuments and college campus buildings commemorating racist individuals were challenged, dismantled, or renamed; that the Treasury Department considered replacing Andrew Jackson with Harriett Tubman on the $20 bill; and that hundreds of white nationalists wielding Tiki torches gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia, for a rally that ended in the death of one young counter-protester and the injury of many more. A century after the bloodshed of 1919, we find ourselves at another moment of reckoning.

Red Summer is available on Casey Ruble’s website.

All images courtesy of Casey Ruble and Conveyor Studio.